Free Speech and Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Spring Newsletter

Official Fan Club Site—www.juicenewtonfanclub.com 2016 Spring Newsletter Hi Everyone, The support and love for Juice has never been as powerful and as proven as it was over the last few months. This issue of the newsletter will feature some new information about Juice and will introduce you to the 2016 “O” Award winner. Paul 1 A Hit All Over Again I am pleased to announce that Juice is once again on the charts with the song that is as classy as she is. ‘Angel of The Morning’ is once again on the charts thanks to the blockbuster movie ‘Deadpool.’ (more on this later) A whole new generation of fans are listening to Juice and have joined the fan club or in- quired about the song. Congratulations Juice!! 'Deadpool' Director Tim Miller and Songwriter Chip Taylor on the Film's Soft-Rock Center- piece, 'Angel in the Morning' (http://www.billboard.com/articles/business/6882938/behind-deadpool-soundtrack-tim-miller-chiptaylor-juice-newton-angel-in-the-morning) “There'll be no strings to bind your hands / Not if my love can't bind your heart.” That’s the first thing you hear over the Marvel logo in the No. 1 movie in the country, Deadpool. As '80s pop country singer Juice Newton sings about an illicit love affair she just can’t shake in her 1981 hit “Angel of the Morning,” Ryan Reynolds’ f-bomb blasting anti-hero gets busy kicking ass. It makes zero sense on the surface, and yet director Tim Miller says that the song was the only track con- sidered to open the superhero flick that grossed another $55 million over the weekend to easily hold on to the No. -

Summer Newsletter

Summer Newsletter www.juicenewtonfanclub.com Hello JNFC Members, I am so glad that this has been a good year for so many of you. Let me say, "WELCOME!" to all of the new members!! This edition of the JNFC Summer Newsletter is full of information about Juice that is sure to get all members excited. I wish everyone, a very happy and fun and most of all safe summer. Sweet, Sweet Juice The year was 1977. Two very talented songwriters collaborated on a song about a someone who had to be set right by their significant every day in order for things to be right. The song was a big hit for the popular brother and sister duo The Carpenters. The song writers were Otha Young and Juice Newton and the song was "Sweet, Sweet Smile." Many people have asked and wondered why Juice never recorded this song herself. They need not wonder any longer. Juice has recorded this classic song on her new compilation "The Ultimate Hits Collection." Juice has recorded a modern rendition of this song. Juice peforms a different tempo and this of course differs from the version that The Carpenters recorded. Juice gave the song a new personality. This CD is available on iTUNES and Amazon.com and other fine retail websites. GET YOURS TODAY!! 1 The Ultimate Hits Collection Tracks Angel of The Morning 1998 Version Love's Been A Little Bit Hard On Me 1998 Version Break It To Me Gently 1998 Version When I Get Over You This Old Flame 1998 Version The Trouble with Angels Hurt Original Version Ride 'em Cowboy 1998 Version Red Blooded American Girl Queen of Hearts 1998 Version The Sweetest Thing (I've Ever Known) 1998 Version Nighttime Without You Ask Lucinda Love Hurts Tell Her No Original Version Heart of The Night Original Version Crazy Little Thing Called Love Funny How Time Slips Away (Duet with Willie Nelson) A Little Love Original Version Sweet, Sweet Smile BRAND NEW RECORDING!!! The mix of newer renditions of some of Juice's classics along with the originals of other tracks makes this a CD that is sure to be entertaining and enjoyable. -

Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician's Perspective

The View from an Open Window: Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician’s Perspective By Danica Wong David Brodbeck, Ph.D. Departments of Music and European Studies Jayne Lewis, Ph.D. Department of English A Thesis Submitted in Partial Completion of the Certification Requirements for the Honors Program of the School of Humanities University of California, Irvine 24 May 2019 i Table of Contents Acknowledgments ii Abstract iii Introduction 1 The Music of Dmitri Shostakovich 9 Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk District 10 The Fifth Symphony 17 The Music of Sergei Prokofiev 23 Alexander Nevsky 24 Zdravitsa 30 Shostakovich, Prokofiev, and The Crisis of 1948 35 Vano Muradeli and The Great Fellowship 35 The Zhdanov Affair 38 Conclusion 41 Bibliography 44 ii Acknowledgements While this world has been marked across time by the silenced and the silencers, there have always been and continue to be the supporters who work to help others achieve their dreams and communicate what they believe to be vital in their own lives. I am fortunate enough have a background and live in a place where my voice can be heard without much opposition, but this thesis could not have been completed without the immeasurable support I received from a variety of individuals and groups. First, I must extend my utmost gratitude to my primary advisor, Dr. David Brodbeck. I did not think that I would be able to find a humanities faculty member so in tune with both history and music, but to my great surprise and delight, I found the perfect advisor for my project. -

RFL063 the Red Chord

CLIENTS DELUXE GATEFOLD LP “The unsettling touch of a gnarled chapped hand tugs at my wrist. A shiver of uneasiness surges through my body that is almost enough to mask the nauseating aroma that surrounds him. “Hey Mister. Got a cigarette?” I quickly pull my arm away as small black insect crawls from his sleeve and falls to ground. My imagination is flying. What happened here? How did it come to be this way? And there are millions just like him. We are all just like him. We are all clients.” Taken from a passage in “Clients” THE RED CHORD has been cited as one of the most influential crossover bands of the hardcore, grind and metal genres. They have been referenced, featured or interviewed in the majority of pertinent heavy music periodicals including Revolver, AP, Metal Hammer, Terrorizer, Unrestrained, Decibel and Brave Words and Bloody Knuckles. This year looks to be the bands biggest year yet, with their new record and some huge tour plans to follow including The New England Hardcore & Metal Fest as well as a co-headlining tour with Bury Your Dead. ARTIST: The Red Chord TITLE: Clients So what should fans of THE RED CHORD’s previous work expect? “It’s a very different album than Fused FORMAT: Deluxe Gatefold LP Together in Revolving Doors. I personally think it’s a lot heavier and angrier, but we’ll let you judge for yourself,” states vocalist Guy Kozowyk. To say Clients is thought provoking is a mere understatement as it HOMETOWN AREA: forces you look at society’s unfortunates and wonder how they became the way they did. -

Music 5364 Songs, 12.6 Days, 21.90 GB

Music 5364 songs, 12.6 days, 21.90 GB Name Album Artist Miseria Cantare- The Beginning Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Pt. 2 Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Bleed Black Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Silver and Cold Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Dancing Through Sunday Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Girl's Not Grey Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Death of Seasons Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Great Disappointment Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Paper Airplanes (Makeshift Wings) Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. This Celluloid Dream Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. But Home is Nowhere Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Hurricane Of Pain Unknown A.L.F. The Weakness Of The Inn Unknown A.L.F. I In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The World Beyond In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Acolytes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Thousand Suns In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Into The Ashes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Smoke and Mirrors In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Semblance Of Life In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Empyrean:Into The Cold Wastes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Floods In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The Departure In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams From A Buried Heart Legend Abigail Williams Like Carrion Birds Legend Abigail Williams The Conqueror Wyrm Legend Abigail Williams Watchtower Legend Abigail Williams Procession Of The Aeons Legend Abigail Williams Evolution Of The Elohim Unknown Abigail Williams Forced Ingestion Of Binding Chemicals Unknown Abigail -

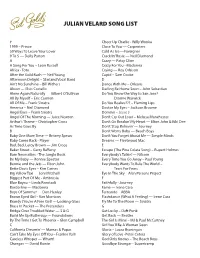

Julian Velard Song List

JULIAN VELARD SONG LIST # Cheer Up Charlie - Willy Wonka 1999 – Prince Close To You — Carpenters 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover Cold As Ice —Foreigner 9 To 5 — Dolly Parton Cracklin’ Rosie — Neil Diamond A Crazy — Patsy Cline A Song For You – Leon Russell Crazy For You - Madonna Africa - Toto Crying — Roy Orbison After the Gold Rush — Neil Young Cupid – Sam Cooke Afternoon Delight – Starland Vocal Band D Ain’t No Sunshine – Bill Withers Dance With Me – Orleans Alison — Elvis Costello Darling Be Home Soon – John Sebastian Alone Again Naturally — Gilbert O’Sullivan Do You Know the Way to San Jose? — All By Myself – Eric Carmen Dionne Warwick All Of Me – Frank Sinatra Do You Realize??? – Flaming Lips America – Neil Diamond Doctor My Eyes – Jackson Browne Angel Eyes – Frank Sinatra Domino – Jesse J Angel Of The Morning — Juice Newton Don’t Cry Out Loud – Melissa Manchester Arthur’s Theme – Christopher Cross Don’t Go Breakin’ My Heart — Elton John & Kiki Dee As Time Goes By Don’t Stop Believin’ — Journey B Don’t Worry Baby — Beach Boys Baby One More Time — Britney Spears Don’t You Forget About Me — Simple Minds Baby Come Back - Player Dreams — Fleetwood Mac Bad, Bad, Leroy Brown — Jim Croce E Baker Street – Gerry Raerty Escape (The Pina Colata Song) – Rupert Holmes Bare Necessities - The Jungle Book Everybody’s Talkin’ — Nilsson Be My Baby — Ronnie Spector Every Time You Go Away – Paul Young Bennie and the Jets — Elton John Everybody Wants To Rule The World – Bette Davis Eyes – Kim Carnes Tears For Fears Big Yellow Taxi — Joni Mitchell Eye In -

Clyde Mcphatter 1987.Pdf

Clyde McPhatter was among thefirst | singers to rhapsodize about romance in gospel’s emotionally charged style. It wasn’t an easy stepfor McP hatter to make; after all, he was only eighteen, a 2m inister’s son born in North Carolina and raised in New Jersey, when vocal arranger and talent manager Billy | Ward decided in 1950 that I McPhatter would be the perfect choice to front his latest concept, a vocal quartet called the Dominoes. At the time, quartets (which, despite the name, often contained more than four members) were popular on the gospel circuit. They also dominated the R&B field, the most popular being decorous ensembles like the Ink Spots and the Orioles. Ward wanted to combine the vocal flamboyance of gospel with the pop orientation o f the R&B quartets. The result was rhythm and gospel, a sound that never really made it across the R &B chart to the mainstream audience o f the time but reached everybody’s ears years later in the form of Sixties soul. As Charlie Gillett wrote in The Sound of the City, the Dominoes began working instinctively - and timidly. McPhatter said, ' ‘We were very frightened in the studio when we were recording. Billy Ward was teaching us the song, and he’d say, ‘Sing it up,’ and I said, 'Well, I don’t feel it that way, ’ and he said, ‘Try it your way. ’ I felt more relaxed if I wasn’t confined to the melody. I would take liberties with it and he’d say, ‘That’s great. -

Top 100 Hits of 1968 Baby the Rain Must Fall— Glen Yarbrough 1

Deveraux — Music 67 to 70 1965 Top 100 Hits of 1968 Baby the Rain Must Fall— Glen Yarbrough 1. Hey Jude, The Beatles Top 100 Hits of 1967 3. Honey, Bobby Goldsboro 1. To Sir With Love, Lulu 4. (Sittin' On) The Dock of the Bay, Otis Redding 2. The Letter, The Box Tops 6. Sunshine of Your Love, Cream 3. Ode to Billie Joe, Bobby Gentry 7. This Guy's In Love With You, Herb Alpert & The Tijuana Brass 5. I'm a Believer, The Monkees 8. The Good, The Bad and the Ugly, Hugo Montenegro 6. Light My Fire, The Doors 9. Mrs. Robinson, Simon and Garfunkel 9. Groovin', The Young Rascals 11. Harper Valley P.T.A., Jeannie C. Riley 10. Can't Take My Eyes Off You, Frankie Valli 12. Little Green Apples, O.C. Smith 13. Respect, Aretha Franklin 13. Mony Mony, Tommy James and The Shondells 24. Ruby Tuesday, The Rolling Stones 14. Hello, I Love You, The Doors 25. It Must Be Him, Vicki Carr 20. Dance to the Music, Sly and The Family Stone 30. All You Need Is Love, The Beatles 25. Judy In Disguise (With Glasses), John Fred & His 31. Release Me (And Let Me Love Again), Engelbert Humperdinck Playboy Band 33. Somebody to Love, Jefferson Airplane 27. Love Child, Diana Ross and The Supremes 35. Brown Eyed Girl , Van Morrison 28. Angel of the Morning, Merrilee Rush 36. Jimmy Mack, Martha and The Vandellas 29. The Ballad of Bonnie & Clyde, Georgie Fame 37. I Got Rhythm, The Happenings 30. -

Of Contemporary Popular Music

Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law Volume 11 Issue 2 Issue 2 - Winter 2009 Article 2 2009 The "Spiritual Temperature" of Contemporary Popular Music Tracy Reilly Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Tracy Reilly, The "Spiritual Temperature" of Contemporary Popular Music, 11 Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law 335 (2020) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw/vol11/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The "Spiritual Temperature" of Contemporary Popular Music: An Alternative to the Legal Regulation of Death-Metal and Gangsta-Rap Lyrics Tracy Reilly* ABSTRACT The purpose of this Article is to contribute to the volume of legal scholarship that focuses on popular music lyrics and their effects on children. This interdisciplinary cross-section of law and culture has been analyzed by legal scholars, philosophers, and psychologists throughout history. This Article specifically focuses on the recent public uproar over the increasingly violent and lewd content of death- metal and gangsta-rap music and its alleged negative influence on children. Many legal scholars have written about how legal and political efforts throughout history to regulate contemporary genres of popular music in the name of the protection of children's morals and well-being have ultimately been foiled by the proper judicial application of solid First Amendment free-speech principles. -

70S Playlist 1/7/2011

70s Playlist 1/7/2011 Song Artist(s) A Song I Like to Sing K. Kristoferson/L Coolidge Baby Come Back Steve Perry Bad, Bad Leroy Brown Jim Croce Don't Stop Fleetwood Mac Father and Son Cat Stevens For my lady Moody Blues Have you seen her The Chi-Lites I Have to say I love you in a Son Jim Croce I want Love Elton John If you Remember Me Kris Kristofferson It's only Love Elvis Presley I've got a thing about you baby Elvis Presley Magic Pilot Moon Shadow Cat Stevens Operator (That's Not the Way it Jim Croce Raised on a Rock Elvis Presley Roses are Red Freddy Fender Someone Saved My Life Tonigh Elton John Steamroller Blues Elvis Presley Stranger Billy Joel We're all alone K. Kristoferson/L Coolidge Yellow River Christie Babe Styx Dancin' in the Moonlight King Harvest Solitaire The Carpenters Take a Walk on the Wild Side Lou Reed Angel of the Morning Olivia Newton John Aubrey Bread Can't Smile Without You Barry Manilow Even Now Barry Manilow Top of the World The Carpenters We've only Just Begun The Carpenters You've Got a Friend James Taylor A Song for You The Carpenters ABC The Jackson 5 After the Love has Gone Earth, Wind and Fire Ain't no Sunshine Bill Withers All I Ever Need is You Sonny and Cher Another Saturday Night Cat Stevens At Midnight Chaka Khan At Seventeen Janis Ian Baby, that's Backatcha Smokey Robinson Baby, I love Your Way Peter Frampton Band on the Run Paul McCartney Barracuda Heart Beast of Burden The Rolling Stones Page 1 70s Playlist 1/7/2011 Song Artist(s) Beautiful Sunday Daniel Boone Been to Canaan Carol King Being -

The Pat Boone Fan Club

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and University of Nebraska Press Chapters 2014 The aP t Boone Fan Club Sue William Silverman Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples Silverman, Sue William, "The aP t Boone Fan Club" (2014). University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters. 293. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples/293 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Nebraska Press at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE PAT BOONE FAN CLUB Buy the Book american lives | series editor: tobias wolff Buy the Book The Pat Boone Fan Club My Life as a White Anglo- Saxon Jew sue william silverman university of nebraska press lincoln and london Buy the Book © 2014 by Sue William Silverman Acknowledgments for the use of copyrighted material appear on pages xi–xii, which constitute an extension of the copyright page. All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Silverman, Sue William. The Pat Boone fan club: my life as a white Anglo- Saxon Jew / Sue William Silverman. pages cm.—(American lives) isbn 978-0-8032-6485-4 (pbk.: alk. paper)— isbn 978-0-8032-6498-4 (pdf)—isbn 978-0-8032- 6499-1 (epub)—isbn 978-0-8032-6500-4 (mobi) 1. Silverman, Sue William. 2. Jews—United States —Biography. -

Censorship in Popular Music Today and Its Influence and Effects on Adolescent Norms and Values Annotated Bibliography

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Musicology and Ethnomusicology: Student Scholarship Musicology and Ethnomusicology 11-2019 Censorship in Popular Music Today and Its Influence and ffE ects on Adolescent Norms and Values Sarah Wagner University of Denver, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/musicology_student Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Wagner, Sarah, "Censorship in Popular Music Today and Its Influence and ffE ects on Adolescent Norms and Values" (2019). Musicology and Ethnomusicology: Student Scholarship. 45. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/musicology_student/45 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This Bibliography is brought to you for free and open access by the Musicology and Ethnomusicology at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Musicology and Ethnomusicology: Student Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Censorship in Popular Music Today and Its Influence and ffE ects on Adolescent Norms and Values This bibliography is available at Digital Commons @ DU: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/musicology_student/45 Censorship in Popular Music Today and its Influence and Effects on Adolescent Norms and Values Annotated Bibliography Anthony, Kathleen S. “Censorship of Popular Music: An Analysis of Lyrical Content.” Masters research paper, Kent State University, 1995. ERIC Institute of Education Sciences. This particular study analyzes and compares the lyrics of popular music from 1986 through 1995, specifically music produced and created in the United States. The study’s purpose is to compare reasons of censorship within different genres of popular music such as punk, heavy metal and gangsta rap.