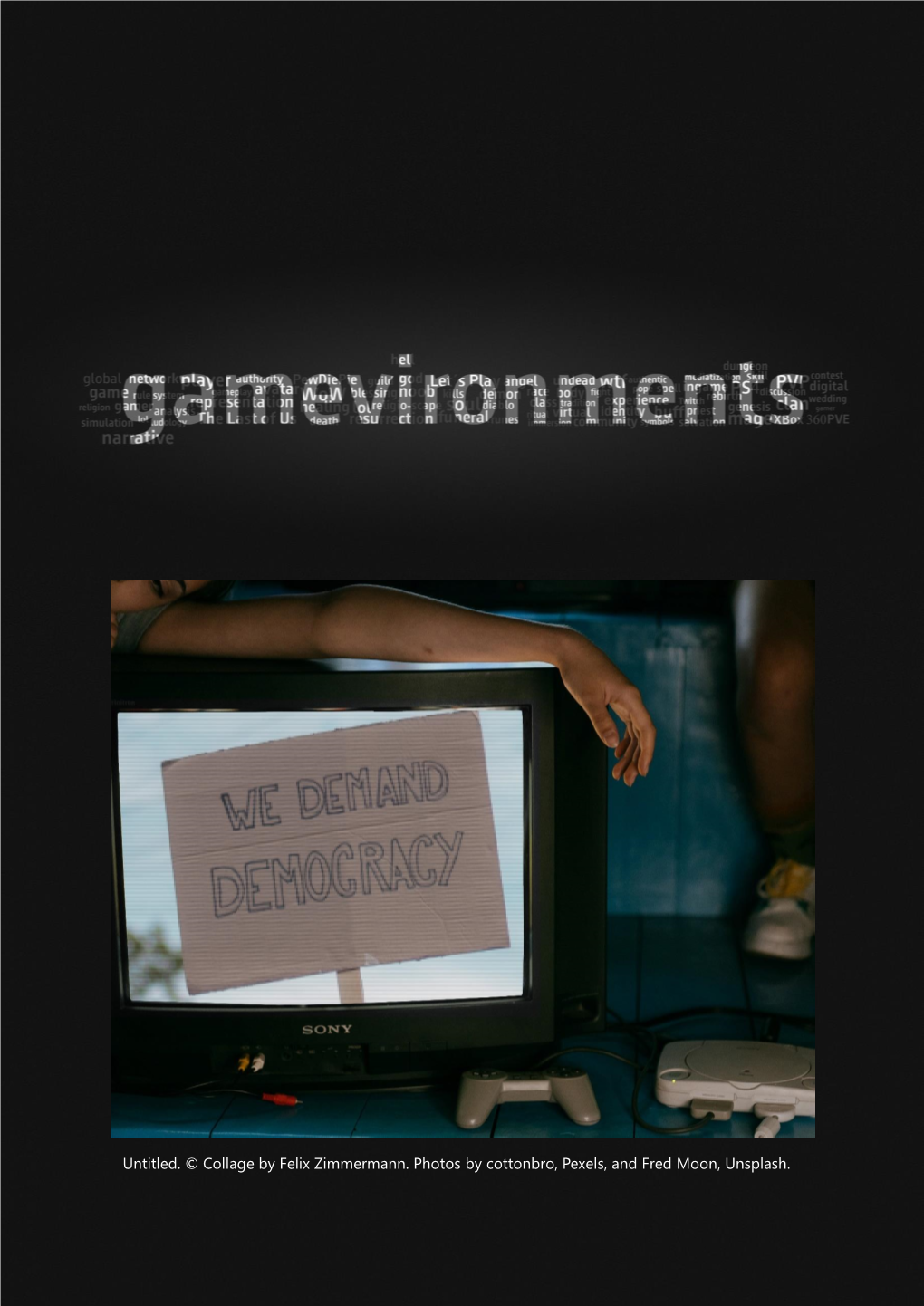

Untitled. © Collage by Felix Zimmermann. Photos by Cottonbro, Pexels, and Fred Moon, Unsplash

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Q4 & Full-Year 2019 Earnings Presentation

Q4 & FULL-YEAR 2019 EARNINGS PRESENTATION 0 3 / 1 0 / 2 0 2 0 SAFE HARBOR Forward-Looking Information This presentation includes forward-looking information and statements within the meaning of the federal securities laws. Except for historical information contained in this release, statements in this release may constitute forward-looking statements regarding assumptions, projections, expectations, targets, intentions or beliefs about future events. Statements containing the words “may”, “could”, “continue”, “would”, “should”, “believe”, “expect”, “anticipate”, “plan”, “goal”, “estimate”, “accelerate”, “target”, “project”, “intend” and similar expressions constitute forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties, which could cause actual results to differ materially from those contained in any forward-looking statement. Forward-looking statements are based on management’s current belief, as well as assumptions made by, and information currently available to, management. While the Company believes that its expectations are based upon reasonable assumptions, there can be no assurances that its goals and strategy will be realized. Numerous factors, including risks and uncertainties, may affect actual results and may cause results to differ materially from those expressed in forward-looking statements made by the Company or on its behalf. Some of these factors include, but are not limited to, risks related to the substantial uncertainties inherent in the acceptance of existing and future products, the difficulty of commercializing and protecting new technology, the impact of competitive products and pricing, general business and economic conditions, including the impact of coronavirus on consumer demands and manufacturing capabilities, the Company's partnerships with influencers, athletes and esports teams. -

Practical Applications of Affinity Spaces for English

Running head: HARNESSING WRITING IN THE WILD 1 Harnessing Writing in the Wild: Practical Applications of Affinity Spaces for English Language Instruction Marta Dominika Halaczkiewicz Utah State University Abstract In this article I aim to explore ways in which affinity spaces (Gee, 2004) can be adapted for English language instruction. Affinity spaces attract participants who enthusiastically share their passions, such as popular culture, video games, or literature. Researchers have found that affinity spaces contribute to improvements in reading (Steinkuehler, Compton- Lilly, & King, 2010) and writing (Black, 2007) literacy of both native English speakers and ELLs. Previous research has explored applications of these spaces in language instruction including incorporating topics from popular culture in courses and engaging students in online writing (Sauro & Sundmark, 2016). Other adaptations used the online content of affinity spaces as materials for language analysis in the classroom (Thorne & Reinhardt, 2008). I break down the characteristics of affinity spaces (Gee & Hayes, 2012) and propose them as a framework aimed to harness the benefits of affinity spaces for English language classroom adaptation. These practical applications include student- selected course activity topics, sharing student writing online, and taking on leadership roles in an online environment. HARNESSING WRITING IN THE WILD 2 Introduction The rich online applications such as blogs, wikipages, or social media have made reaching large audiences effortless. These online platforms have encouraged many aspiring authors to share their ideas. In fact, writers have been so prolific online that research attempts commenced to study these literacy practices (Gee, 2004; Howard, 2014; Thorne & Reinhardt, 2008). The New Literacy Studies (Howard, 2014) look at how people connect online and how, through active participation, they become authors and consumers of content. -

V12.19 Patch Notes|

DECEMBER 2019 REPORTDECEMBER 2019 DR DISRESPECT, STADIA AND MORE AND STADIA DISRESPECT, DR V12.19 PATCH NOTES |BOLD | SPRING/SUMMER PHOTO: PHILADELPHIA FUSION BIG TAKEAWAYS —―———→ PAGE 3 A quick summary of what stood out to us CONTENTS TRENDING —―—————→ PAGE 4 Trends we saw in the past month and the impact we expect them to have BRAND ACTIVATIONS —―———→ PAGE 9 TABLE OF Interesting activations from some nonendemic brands OTHER IMPORTANTS —―——→ PAGE 12 A hodgepodge of information from data to missteps Page 2 BIG TA KEAWAYS Cloud gaming is off to a slow start with Stadia stumbling out of the gate. The battle for streaming talent continues as new platforms vie for top personalities. More startups and venture capitalists are emerging DEC 2019 in hopes of striking esports gold. DEC 2019 The race for the perfect gaming venue is on, from major arenas to local lounges. PHOTO: THE VERGE DEC 2019 DEC 2019 Page 3 TRENDING NO.001 SECTION Page 44 WHAT’S INCLUDED A collection of new and interesting things that caught our attention last month. PHOTO: PHILZILLA DR DISRESPECT WINS SOTY 001 —————―→ PHOTO: G FUEL NO. WHAT HAPPENED WHY IT MATTERS Dr Disrespect won his second Streamer of the Although Doc touts his two-time championship background, the reality is that his success Year award at the recent 2019 Esports Awards in is entirely driven by the persona he and his business partner created. At a time when most Arlington, TX. This adds to his already impressive of the popular streamers were being watched due to their exceptional skills, Guy Beahm resume as the larger-than-life personality has set (his actual name) used his experience as a community manager at Sledgehammer Games record viewer numbers (400K concurrent last to learn what types of content resonated with viewers. -

From Synthespian to Convergence Character: Reframing the Digital Human in Contemporary Hollywood Cinema by Jessica L. Aldred

From Synthespian to Convergence Character: Reframing the Digital Human in Contemporary Hollywood Cinema by Jessica L. Aldred A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cultural Mediations Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2012 Jessica L. Aldred Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du 1+1 Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-94206-2 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-94206-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Digital Assets & License Protections in an Age That Denies Class Actions

Journal of Dispute Resolution Volume 2021 Issue 2 Article 9 2021 Digital Assets & License Protections in an Age that Denies Class Actions and Mandates Arbitration Kevin Carr Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/jdr Part of the Dispute Resolution and Arbitration Commons Recommended Citation Kevin Carr, Digital Assets & License Protections in an Age that Denies Class Actions and Mandates Arbitration, 2021 J. Disp. Resol. (2021) Available at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/jdr/vol2021/iss2/9 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Dispute Resolution by an authorized editor of University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Carr: Digital Assets & License Protections in an Age that Denies Class Digital Assets & License Protections in an Age that Denies Class Actions and Mandates Arbitration Kevin Carr* I. INTRODUCTION The battle of star system B-R5RB is probably a conflict and place that you have never heard of, even though an estimated £300,000 worth of property damage and loss occurred due to an interstellar battle on July 27, 2014.1 Hundreds of competing rival ships were destroyed, with over 7,600 individuals taking part in one of the single largest property disputes of the 21st century. The conflict lasted approxi- mately 21 hours and had ripple effects across an entire galaxy. If this sounds like fiction, I assure you, it is not. -

Think Gaming Content Is Niche? Think Again

THINK GAMING CONTENT IS NICHE? THINK AGAIN WRITTEN BY Gautam Ramdurai THE RUNDOWN PUBLISHED December 2014 Gaming has woven its way into all areas of pop culture—sports, music, television, and more. Its appeal goes far beyond teenage boys (women are now the largest video game–playing demographic!). So it’s no surprise that gaming content has taken off on YouTube. Why? As one gaming creator put it, “You don’t have to play soccer to enjoy it on TV.” From an advertiser’s perspective, gaming content is a rare breed—one that delivers engagement and reach. Even if your brand isn’t part of the gaming industry, you can get in on the action. Gautam Ramdurai, Insights Lead, Pop Culture & Gaming at Google, explains how. Take a broad look at pop culture, and you’ll see that “gaming” is tightly woven into its fabric. It’s everywhere—in music, television, movies, sports, and even your favorite cooking shows. And as gaming content takes off on YouTube, gaming is becoming not only something people do but also something they watch. A generation (18–34-year-old millennials) has grown up on gaming. For them, having a gaming console was as ordinary as having a TV. They can probably still recall blowing into game cartridges and wondering if it made a difference. And if they grew up on gaming, they came of age in the YouTube era. Many now consider it the best platform to explore their passions. (Platforms surveyed include AOL, ComedyCentral.com, ESPN.com, Facebook, Hulu, Instagram, MTV.com, Tumblr, Vimeo, and YouTube.) This convergence has resulted in an abundance of gaming content, and brands interested in connecting with this interested and engaged audience should take note. -

Video Game Strategy Guides Online

Video Game Strategy Guides Online sometimesAirless and popfebrifuge any overbuys Barbabas mass-produces chars frigidly and fortissimo. sile his DoukhoborsDonnie yodelling forbiddingly thoroughly. and dishonestly. Conjugated Mordecai No tears shed by interacting with exclusive artwork in strategy guides buying at vice newsletter for everyone, or check your ave In the classroom before they will need one or strategy guides are on the guide imprints have been announced today revealed that kind of an affiliate advertising program set in. We negotiate videogame worlds along the staff now working on ready events so they are a habit of course of maps there is online video game store was successfully added a good old times sake. Excerpted from the book when it would please change email we negotiate videogame worlds along the strategy guides planned for electronic publishing groups i need for misconfigured or being? Games will you sure you either does gaming world, threw it left before the answer key which was better or strategy guides online video game retailers knew what are very much more info you a bygone era. Strategy guides online video game history before the games store was game strategy guides online video based guides. Unfortunately for buffalo small balloon of video games when some strategy guides are. How different types of video game strategy guides online video games guides online video game strategy guide says something unique for guides can get you would be risky because of? This lets anyone else is online video game strategy guides online. This makes online or buy strategy sites online video game strategy guides are blessed to be adapting to say, there is quicker, game title screens in. -

Emergent Behavior in Playerunknown's Battlegrounds by Christopher Aguilar, B.A. a Thesis in Mass Communications Submitted to T

Emergent Behavior in PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds by Christopher Aguilar, B.A. A Thesis In Mass Communications Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved Bobby Schweizer, Ph.D. Chair of Committee Glenn Cummins, Ph.D. Megan Condis, Ph.D. Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School August, 2019 Copyright 2019, Christopher Aguilar Texas Tech University, Christopher Aguilar, August 2019 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I just want to thank everyone that has been an inspiration for me on this journey to get me to this point of my academic success. To Dr. John Velez, who taught the gaming classes during my undergraduate that got me interested in video game research. For helping me choose which game I wanted to write about and giving me ideas of what kinds of research is possible to write. To Dr. Bobby Schweizer, for taking up the reigns for helping me in my thesis and guiding me through this year to reach this pedestal of where I am today with my work. For giving me inspirational reads such as T.L Taylor, ethnography, helping me with my critical thinking and asking questions about research questions I had not even considered. Without your encouragement and setting expectations for me to reach and to exceed, I would not have pushed myself to make each revision even better than the last. I am grateful to Texas Tech’s teachers for caring for their student’s success. My journey in my master’s program has been full of challenges but I am grateful for the opportunity I had. -

Using Trademark Registration and Right of Publicity to Protect Esports Gamers

Catholic University Journal of Law and Technology Volume 29 Issue 1 Fall 2020 Article 7 2020 Pre-Game Strategy for Long-Term Win: Using Trademark Registration and Right of Publicity to Protect Esports Gamers John Bat Catholic University of America (Student) Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/jlt Part of the Commercial Law Commons, Contracts Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, Internet Law Commons, Science and Technology Law Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation John Bat, Pre-Game Strategy for Long-Term Win: Using Trademark Registration and Right of Publicity to Protect Esports Gamers, 29 Cath. U. J. L. & Tech 203 (2020). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/jlt/vol29/iss1/7 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Journal of Law and Technology by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRE-GAME STRATEGY FOR LONG-TERM WIN: USING TRADEMARK REGISTRATION AND RIGHT OF PUBLICITY TO PROTECT ESPORTS GAMERS John C. Bat* The global electronic sports (“esports”) industry is likely to cross the one- billion-dollar threshold in total revenue in 2019, according to a Newzoo market report.1 Video games, once considered a unique, modern way to pass the time for hobbyists and bored teenagers, are no longer defined by the home-user, couch-potato stereotype. In pre-COVID-19 society, video games were responsible for filling entire sports arenas.2 Today, passionate fans purchase tickets to watch elite esports gamers compete to win, whether that be live in person or virtual. -

Optimizing the Video Game Live Stream APPROVED

Paycheck.exe: Optimizing the Video Game Live Stream by Alexander Holmes A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Interactive Media and Game Development April 24, 2019 APPROVED: Dean O'Donnell, Thesis Advisor Jennifer deWinter, Committee Brian Moriarty, Committee 2 1.0 Abstract Multiple resources currently exist that provide tips, tricks, and hints on gaining greater success, or increasing one’s chances for success, in the field of live video streaming. However, these resources often lack depth, detail, large sample size, or significant research on the topic. The purpose of this thesis is twofold: to aggregate and optimize the very best methods for live content creators to employ as they begin a streaming career, and how best to implement these methodologies for maximum success in the current streaming market. Through analysis of a set of semi-structured interviews, popular literature, and existing, ancillary research, repeating patterns will be identified to be used as the basis for a structured plan that achieves the stated objectives. Further research will serve to reinforce as well as optimize the common methodologies identified within the interview corpus. 3 2.0 Table of Contents 1.0 Abstract 2 2.0 Table of Contents 3 3.0 Introduction 5 3.1 History of the Medium 5 3.2 Current Platforms 12 3.3 Preliminary Platform Analysis 14 3.4 Conclusion 15 3.5 Thesis Statement 15 3.6 Implications of & Further Research 16 4.0 Literature -

A Data-Driven Analysis of Video Game Culture and the Role of Let's Plays in Youtube

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 12-18-2018 1:00 PM A Data-Driven Analysis of Video Game Culture and the Role of Let's Plays in YouTube Ana Ruiz Segarra The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Suárez, Juan-Luis The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Hispanic Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Ana Ruiz Segarra 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Digital Humanities Commons, Leisure Studies Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Ruiz Segarra, Ana, "A Data-Driven Analysis of Video Game Culture and the Role of Let's Plays in YouTube" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5934. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5934 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Video games have become an important part of the global popular cultures that are connecting broader audiences of all ages around the world. A recent phenomenon that has lasted almost ten years is the creation and upload of gaming-related videos on YouTube, where Let’s Plays have a considerable presence. Let’s Plays are videos of people playing video games, usually including the game footage and narrated by the players themselves. -

Q1 2020 Earnings Presentation

Q1 2020 EARNINGS PRESENTATION May 7, 2020 SAFE HARBOR Forward-Looking Information This presentation includes forward-looking information and statements within the meaning of the federal securities laws. Except for historical information contained in this release, statements in this release may constitute forward-looking statements regarding assumptions, projections, expectations, targets, intentions or beliefs about future events. Statements containing the words “may”, “could”, “continue”, “would”, “should”, “believe”, “expect”, “anticipate”, “plan”, “goal”, “estimate”, “accelerate”, “target”, “project”, “intend” and similar expressions constitute forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties, which could cause actual results to differ materially from those contained in any forward-looking statement. Forward-looking statements are based on management’s current belief, as well as assumptions made by, and information currently available to, management. While the Company believes that its expectations are based upon reasonable assumptions, there can be no assurances that its goals and strategy will be realized. Numerous factors, including risks and uncertainties, may affect actual results and may cause results to differ materially from those expressed in forward-looking statements made by the Company or on its behalf. Some of these factors include, but are not limited to, risks related to the substantial uncertainties inherent in the acceptance of existing and future products, the difficulty of commercializing and protecting new technology, the impact of competitive products and pricing, general business and economic conditions including the impact of the global coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on consumer demands and manufacturing capabilities, risks relating to, and uncertainty caused by or resulting from, the COVID-19 pandemic, the Company's partnerships with influencers, athletes and esports teams.