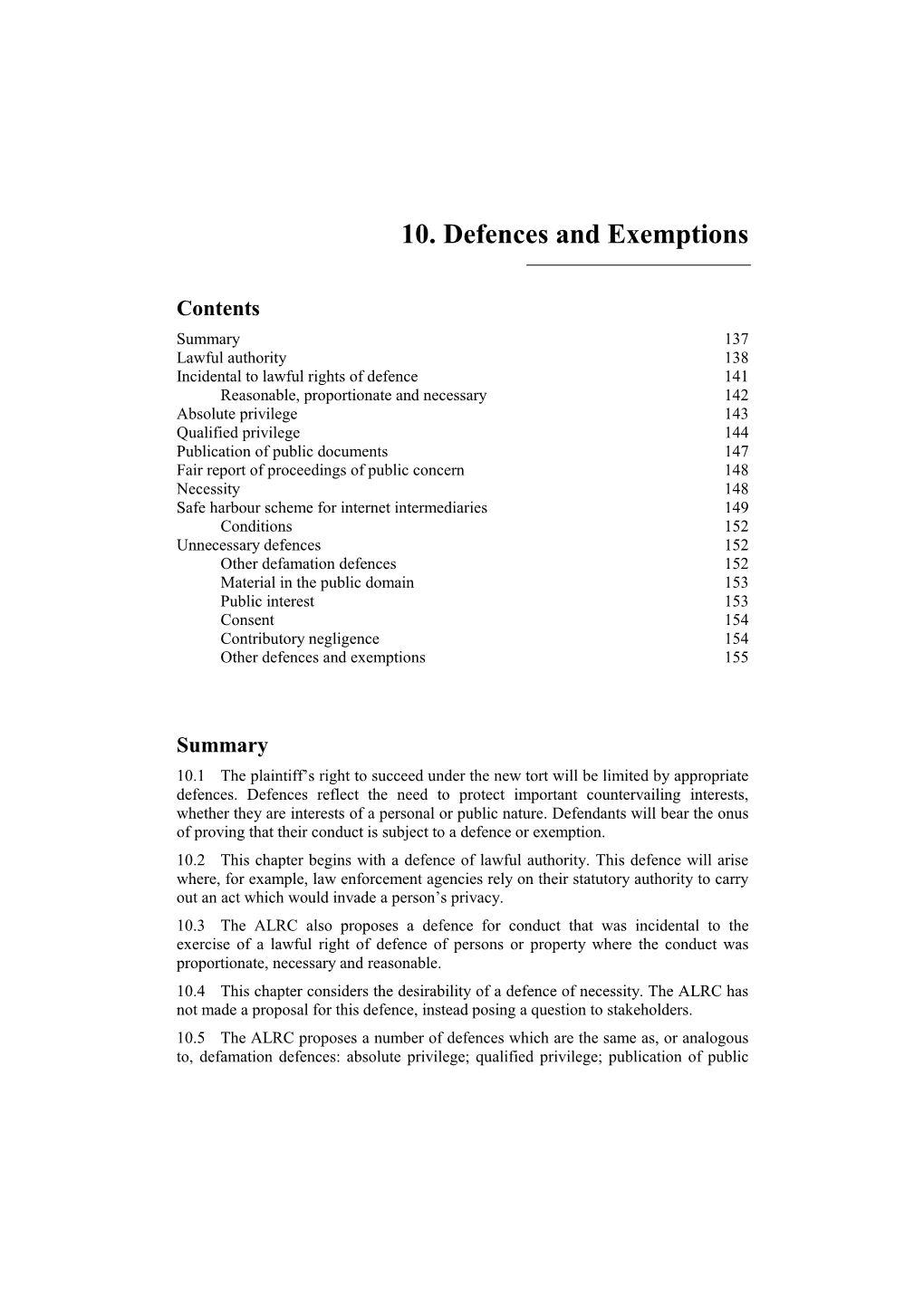

10. Defences and Exemptions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FATE MANAGEMENT: the Real Target of Modern Criminal Law

FATE MANAGEMENT: The Real Target of Modern Criminal Law W.B. Kennedy Doctor of Juridical Studies 2004 University of Sydney © WB Kennedy, 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT vii PREFACE ix The Thesis History x ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS xiii TABLE OF CASES xv TABLE OF LEGISLATION xix New South Wales xix Other Australian jurisdictions xix Overseas municipal statute xx International instruments xx I INTRODUCTION 1 The Issue 1 The Doctrinal Background 4 The Chosen Paradigm 7 The Hypothesis 9 The Argument 13 Why is This Reform Useful? 21 Methodology 21 Structure ............................................................................24 II ANTICIPATORY OFFENCES 27 Introduction 27 Chapter Goal 28 Conspiracy and Complicity 29 Attempt 31 Arguments for a discount ......................................................33 The restitution argument 33 The prevention argument 34 Arguments for no discount .....................................................35 Punishment as retribution 35 Punishment as prevention 35 The objective argument: punish the violation 35 The subjective argument: punish the person 37 The anti-subjective argument 38 The problems created by the objective approach .......................39 The guilt threshold 39 Unlawful killing 40 Involuntary manslaughter 41 The problems with the subjective approach ..............................41 Impossibility 41 Mistake of fact 42 Mistake of law 43 Recklessness 45 Oppression 47 Conclusion 48 FATE MANAGEMENT III STRICT LIABILITY 51 Introduction 51 Chapter Goal 53 Origins 54 The Nature of Strict Liability -

The Human Right of Self-Defense, 22 BYU J

Brigham Young University Journal of Public Law Volume 22 | Issue 1 Article 3 7-1-2007 The umH an Right of Self-Defense David B. Kopel Paul Gallant Joanne D. Eisen Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/jpl Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, and the Second Amendment Commons Recommended Citation David B. Kopel, Paul Gallant, and Joanne D. Eisen, The Human Right of Self-Defense, 22 BYU J. Pub. L. 43 (2007). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/jpl/vol22/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brigham Young University Journal of Public Law by an authorized editor of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Human Right of Self-Defense David B. Kopel,1 Paul Gallant2 & Joanne D. Eisen3 I. INTRODUCTION “Any law, international or municipal, which prohibits recourse to force, is necessarily limited by the right of self-defense.”4 Is there a human right to defend oneself against a violent attacker? Is there an individual right to arms under international law? Conversely, are governments guilty of human rights violations if they do not enact strict gun control laws? The United Nations and some non-governmental organizations have declared that there is no human right to self-defense or to the possession of defensive arms.5 The UN and allied NGOs further declare that 1. Research Director, Independence Institute, Golden, Colorado; Associate Policy Analyst, Cato Institute, Washington, D.C., http://www.davekopel.org. -

Defamation and Parliamentarians

Defamation and Parliamentarians _It is well known that no action for defamation can be founded on a statement made by a member of parliament In a speech made In the House. But should parliamentarians also be protected from defamation proceedings for material _____________________ they publish outside the House?___________________ _____ la this article Sally Walker explores the Victorian provision, the sections are the extent of the protection given to “ Members of expressed to apply to reports of “proceedings members of parliament as well as media Parliament may be of a House” rather than “parliamentary pro organisations olio publish reports of ceedings”6 It follows that, except in Victoria, defamatoiy statements made by protected from liability to obtain qualified privilege for the publica parliamentarians. tion of a fair and accurate report of proceed when they publish ings which did not take place in the House, a defamatory material media organisation would have torelyonthe he absolute privilege accorded to common law. This would be possible in all Members of Parliament against lia outside their Houses of jurisdictions except Queensland, Tasmanian bility for defamation is based on Ar and Western Australian where the statutory ticle 9 of the Bill of Rights (1688). Parliament.” provisions are partof acode. In these jurisdic Article 9 declares that; tions a media organisation could, however, T“the freedom of speech and debates or rely on the qualified privilege accorded to the proceedings in Parliament ought not to be tion of the material is part of “proceedings in publication of material “for the purpose of impeached or questioned in any court or parliament”. -

Dismantling the Purported Right to Kill in Defence of Property Kenneth Lambeth*

Dismantling the Purported Right to Kill in Defence of Property Kenneth Lambeth* Two of the most fundamental western legal principles are the right to life and the right to own property. But what happens when life and property collide? Such a possibility exists within the realm of criminal law where a person may arguably be acquitted for killing in defence of property. Unlike life, property has never been a fundamental right,1 but a mere privilege2 based upon the power to exclude others. Killing in defence of property, without something more,3 can therefore never be justified. The right to life is now recognised internationally4 as a fundamental human right, that is, a basic right available to all human beings.5 Property is not, nor has it ever been, such a universal right. The common law has developed “without explicit reference to the primacy of the right to life”.6 However, the sanctity of human life, from which the right to life may be said to flow, predates the common law itself. This article examines two main sources to show that, wherever there is conflict between the right to life and the right to property, the right to life must prevail. The first such source is the historical, legal and social * Final year LLB student, Southern Cross University. A sincere and substantial debt of gratitude is owed to Professor Stanley Yeo for his support, guidance and inspiration. 1 The word ‘fundamental’ is defined in the Macquarie Dictionary to mean ‘essential; primary; original’. A ‘right’ is defined as ‘a just claim or title, whether legal, prescriptive or moral’: Delbridge, A et al (eds), The Macquarie Dictionary (3rd Ed), Macquarie Library, NSW, 1998, pp 859, 1830. -

Criminal Code 2003.Pmd 273 11/27/2004, 12:35 PM 274 No

273 No. 9 ] Criminal Code [2004. SAINT LUCIA ______ No. 9 of 2004 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS CHAPTER ONE General Provisions PART I PRELIMINARY Section 1. Short title 2. Commencement 3. Application of Code 4. General construction of Code 5. Common law procedure to apply where necessary 6. Interpretation PART II JUSTIFICATIONS AND EXCUSES 7. Claim of right 8. Consent by deceit or duress void 9. Consent void by incapacity 10. Consent by mistake of fact 11. Consent by exercise of undue authority 12. Consent by person in authority not given in good faith 13. Exercise of authority 14. Explanation of authority 15. Invalid consent not prejudicial 16. Extent of justification 17. Consent to fight cannot justify harm 18. Consent to killing unjustifiable 19. Consent to harm or wound 20. Medical or surgical treatment must be proper 21. Medical or surgical or other force to minors or others in custody 22. Use of force, where person unable to consent 23. Revocation annuls consent 24. Ignorance or mistake of fact criminal code 2003.pmd 273 11/27/2004, 12:35 PM 274 No. 9 ] Criminal Code [2004. 25. Ignorance of law no excuse 26. Age of criminal responsibility 27. Presumption of mental disorder 28. Intoxication, when an excuse 29. Aider may justify same force as person aided 30. Arrest with or without process for crime 31. Arrest, etc., other than for indictable offence 32. Bona fide assistant and correctional officer 33. Bona fide execution of defective warrant or process 34. Reasonable use of force in self-defence 35. Defence of property, possession of right 36. -

IN the HIGH COURT of UGANDA SITTING at GULU Reportable Civil Suit No

IN THE HIGH COURT OF UGANDA SITTING AT GULU Reportable Civil Suit No. 12 of 2009 In the matter between 1. ENG. BARNABAS OKENY } 2. WALTER OKIDI LADWAR } 3. JAMES ONYING PENYWII } PLAINTIFFS 4. DAVID OKIDI } 5. BEST SERVICES CO. LIMITED } And PETER ODOK W'OCENG DEFENDANT Heard: 12 February 2019 Delivered: 28 February 2019 Summary: libel and the defences of qualified privilege and qualified immunity. ______________________________________________________________________ JUDGMENT ______________________________________________________________________ STEPHEN MUBIRU, J. Introduction: [1] The plaintiffs jointly and severally sued the defendant for general damages for libel, exemplary damages, an injunction restraining him from further publication of slanderous and libellous material against them, interest and costs. The defendant was at the material time Chairman of Pader District Local Government [2] Their claim is that on diverse occasions starting on 3rd December, 2007 the defendant wrote a series of letters of and about them, addressed to the IGG calling for investigations into the financial mismanagement in the District (exhibit 1 P.E.1). On 6th October, 2008 he wrote a letter addressed to the Minister of Local government over a similar subject (exhibit P.E.2); on 25th November, 2008 he wrote another letter addressed to IGG over a similar subject (exhibit P.E.3); on 19th January, 2009 he wrote another letter addressed to IGG on the same subject (exhibit P.E.4). The letters were copied to several people including personnel from the print (exhibit P.E.5) and electronic media. The subject if the defendant's complaint in those letters received wide media coverage in both forms. The contents of those letters was defamatory of the plaintiffs and as a result of their publication, the reputation and public image of each of the plaintiffs was damaged. -

Albin Eser Grounds for Excluding Criminal Responsibility Article 31

Sonderdrucke aus der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg ALBIN ESER Grounds for excluding criminal responsibility [Article 31 of the Rome Statute] Originalbeitrag erschienen in: Otto Triffterer (Hrsg.): Commentary on the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. München [u.a.]: Beck [u.a.], 2008, S. 863-893 ALBIN ESER GROUNDS FOR EXCLUDING CRIMINAL RESPONSIBILITY [Article 31 of the Rome Statute] Reprint from: Otto Triffterer (ed.) Commentary on the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court - Second Edition - C.H. Beck/Munchen • HartiVolkach • Nomos/Baden-Ba,den 2008 Article 31 Grounds for excluding criminal responsibility 1. In addition to other grounds for exc1udin4 criminal responsibility provided for in this Statute, a person shall not be criminally responsible if, at the time of that person's conduct: (a) The person suffers from a mental disease or defect that destroys that person's capacity to appreciate the unlawfulness or nature of his or her conduct, or capacity to control his or her conduct to conform to the requirements of law; (b) The person is in a state of intoxication that destroys that person's capacity to appreciate the unlawfulness or nature of his or her conduct, or capacity to control his or her conduct to conform to the requirements of law, unless the person has become voluntarily intoxicated under such circumstances that the person knew, or disregarded the risk, that, as a result of the intoxication, he or she was likely to engage in conduct constituting a crime within the jurisdiction of the Court; (c) The person acts reasonably to defend himself or herself or another person or, in the case of war crimes, property which Is essential for the survival of the person or another person or property which is essential for accomplishing a military mission, against an imminent and unlawful use of force in a manner proportionate to the degree of danger to the person or the other person or property protected. -

Vellacott V Saskatoon Starphoenix Group Inc. 2012 SKQB

QUEEN'S BENCH FOR SASKATCHEWAN Citation: 2012 SKQB 359 Date: 2012 08 31 Docket: Q.B.G. No. 1725 I 2002 Judicial Centre: Saskatoon IN THE COURT OF QUEEN'S BENCH FOR SASKATCHEWAN JUDICIAL CENTRE OF SASKATOON BETWEEN: MAURICE VELLACOTT, Plaintiff -and- SASKATOON STARPHOENIX GROUP INC., DARREN BERNHARDT and JAMES PARKER, Defendants Counsel: Daniel N. Tangjerd for the plaintiff Sean M. Sinclair for the defendants JUDGMENT DANYLIUKJ. August 31,2012 Introduction [1] The cut-and-thrust of politics can be a tough, even vicious, business. Not for the faint of heart, modem politics often means a participant's actions are examined - 2 - under a very public microscope, the lenses of which are frequently controlled by the media. While the media has obligations to act responsibly, there is no corresponding legal duty to soothe bruised feelings. [2] The plaintiff seeks damages based on his allegation that the defendants defamed him in two newspaper articles published in the Saskatoon Star-Phoenix newspaper on March 4 and 5, 2002. The defendants state the words complained of were not defamatory and, even if they were, that they have defences to the claim. [3] To better organize this judgment, I have divided it into the following sections: Para~raphs Facts 4-45 Issues 46 Analysis 47- 115 1. Are the words complained of defamatory? 47-73 2. Does the defence of responsible journalism avail the defendants? 74-83 3. Does the defence of qualified privilege avail the defendants? 84-94 4. Does the defence of fair comment avail the defendants? 95- 112 5. Does the defence of consent avail the defendants? 113 6. -

Common Law Division Supreme Court New South Wales

Common Law Division Supreme Court New South Wales Case Name: O'Brien v Australian Broadcasting Corporation Medium Neutral Citation: [2016] NSWSC 1289 Hearing Date(s): 91 10, 11, 12, 13, 16 November2015 Date of Decision: 15 September 2016 Jurisdiction: Common law Before: Mccallum J Decision: Judgment for the defendant Catchwords: DEFAMATION - Media Watch programme analysing articles written by a journalist about the results of tests for toxic substances - imputations that the journalist engaged in trickery by misrepresenting the location of the tests and that she created unnecessary concern in the community by irresponsibly failing to consult experts in the preparation of her article - defences of fair comment at common law and statutory defence of honest opinion - whether defamation conveyed as the comment or opinion of the presenter - defence of truth - whether imputations substantially true - defence of contextual truth - whether open to defendant to rely on an alternative, fall-back imputation pleaded by the plaintiff - whether open to plaintiff to rely on an imputation of which she complained but which was proved true - consideration of the decision of the Queensland Court of Appeal in Mizikovsky - whether because of the substantial truth of the contextual imputations the (untrue) defamatory imputation did not further harm the plaintiff's reputation - defence of qualified privilege at common law - whether the Media Watch programme was published on an occasion of qualified privilege at common law Legislation Cited: Defamation Act 2005 -

Defences, Mitigation and Criminal Responsibility

Chapter 12 Defences, mitigation and criminal responsibility Page Index 1-12-1 Introduction 1-12-2 Part 1 - Defences 1-12-3 General defences 1-12-4 Intoxication/drunkenness due to drugs/alcohol 1-12-4 Self defence 1-12-4 Use of force in prevention of crime 1-12-5 Mistake 1-12-5 Duress 1-12-6 Necessity 1-12-6 Insanity 1-12-6 Automatism 1-12-6 Other defences 1-12-7 Provocation 1-12-7 Alibi 1-12-7 Diminished responsibility 1-12-7 Consent 1-12-7 Superior orders 1-12-7 Part 2 - Mitigation 1-12-9 Part 3 - Criminal responsibility 1-12-10 Intention 1-12-10 Recklessness 1-12-10 Negligence 1-12-10 Lawful excuse or reasonable excuse – the burden of proof 1-12-11 Evidential burden 1-12-11 Lawful excuse 1-12-11 Reasonable excuse 1-12-11 JSP 830 MSL Version 2.0 1-12-1 AL42 35 Chapter 12 Defences, mitigation and criminal responsibility Introduction 1. This chapter is divided into three parts: a. Part 1 - Defences (paragraphs 4 - 28); b. Part 2 - Mitigation (paragraphs 29 - 31); and c. Part 3 - Criminal responsibility (paragraphs 32 - 44). 2. This chapter provides guidance on these matters to those involved in the administration of Service discipline at unit level. Related chapters are Chapter 9 (Summary hearing and activation of suspended sentences of Service detention), Chapter 6 (Investigation, charging and mode of trial), and Chapter 11 (Summary hearing - dealing with evidence). 3. This is not a detailed analysis of the law on the most common defences likely to be put forward by an accused, but when read in conjunction with the chapters mentioned above, should provide enough information for straightforward cases to be dealt with and ensure that staffs can identify when a case should be referred for Court Martial (CM) trial. -

Rethinking Sullivan: New Approaches in Australia, New Zealand and England

The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law CUA Law Scholarship Repository Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions Faculty Scholarship 2002 Rethinking Sullivan: New Approaches in Australia, New Zealand and England Susanna Frederick Fischer The Catholic University, Columbus School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/scholar Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Susanna Frederick Fischer, Rethinking Sullivan: New Approaches in Australia, New Zealand and England, 34 GEO. WASH. INT’L L. REV. 101 (2002). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions by an authorized administrator of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RETHINKING SULLIVAN: NEW APPROACHES IN AUSTRALIA, NEW ZEALAND, AND ENGLAND SUSANNA FREDERICK FISCHER* "This is a difficult problem. No answer is perfect." - Lord Nicholls of Birkenhead in Reynolds v. Times Newspapers1 SUMMARY This Article employs a comparative analysis of some important recent Commonwealth libel cases to analyze what has gone wrong with U.S. defa- mation law since New York Times v. Sullivan and to suggest a new direc- tion for its reform. In Lange v. Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Lange v. Atkinson, and Reynolds v. Times Newspapers, the highest courts of the Australian, New Zealand, and English legal systems were con- fronted with the same challengefaced by the U.S. Supreme Court in New York Times v. Sullivan. They had to decide the proper constitutionalbal- ance between protection of reputation and protection of free expression in defamation actions brought by public officials over statements of fact. -

Internet Service Provider Liability for Defamation

INTERNET SERVICE PROVIDER LIABILITY FOR DEFAMATION: UNITED STATES AND UNITED KINGDOM COMPARED by AHRAN PARK A DISSERTATION Presented to the School of Journalism and Communication and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2015 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Ahran Park Title: Internet Service Provider Liability for Defamation: United States and United Kingdom Compared This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the School of Journalism and Communication by: Kyu Ho Youm Chairperson Timothy Gleason Core Member Kim Sheehan Core Member Ofer Raban Core Member Daniel Tichenor Institutional Representative and J. Andrew Berglund Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded March 2015 ii © 2015 Ahran Park iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Ahran Park Doctor of Philosophy School of Journalism and Communication March 2015 Title: Internet Service Provider Liability for Defamation: United States and United Kingdom Compared Since the mid-1990s, American Internet Service Providers (ISPs) have enjoyed immunity from liability for defamation under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. As Congress originally intended in 1996, Section 230 has strongly protected freedom of online speech and allowed ISPs to thrive with little fear of being sued for online users’ comments. Such extraordinary statutory immunity for ISPs reflects American free-speech tradition that freedom of speech is preferred to reputation. Although the Internet landscape has changed over the past 20 years, American courts have applied Section 230 to shield ISPs almost invariably.