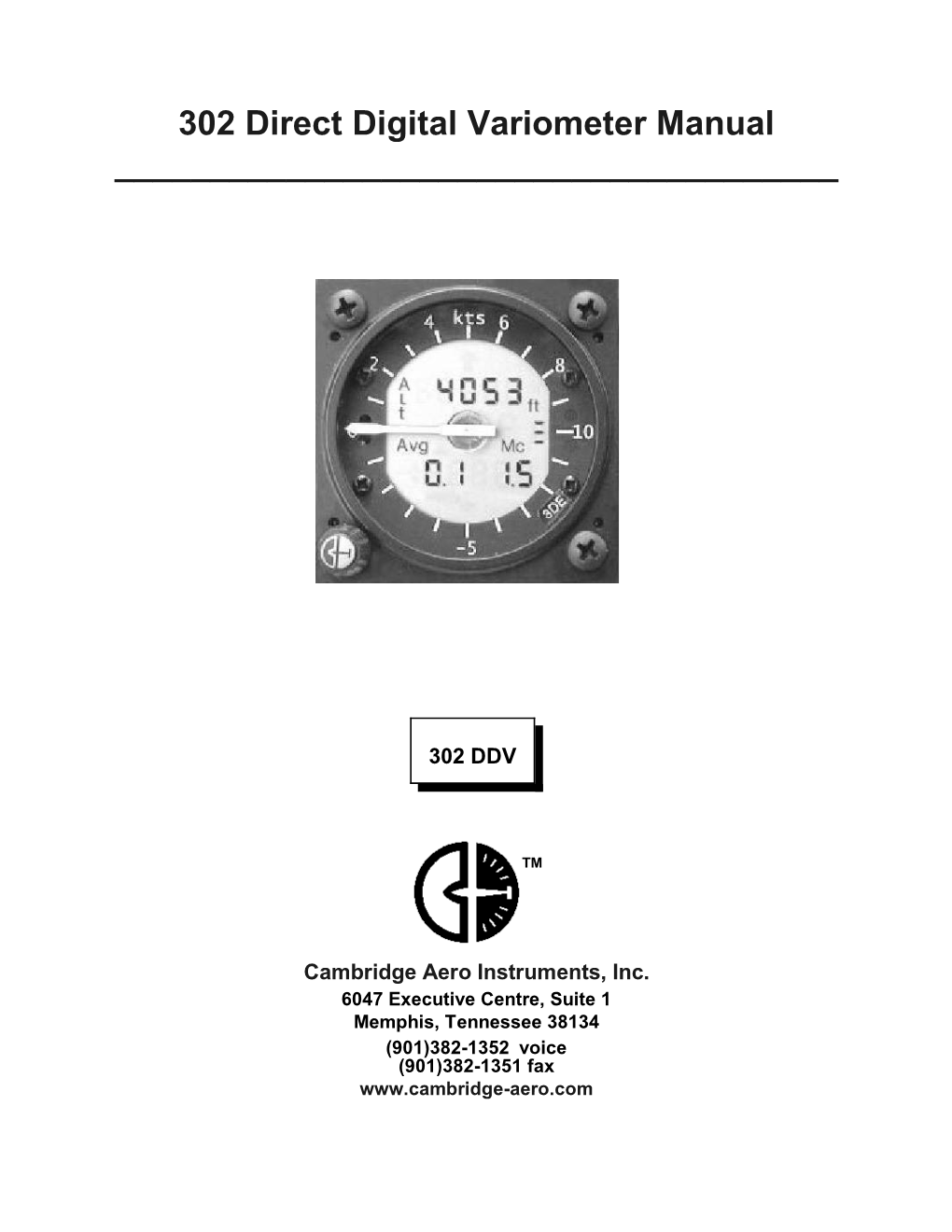

302 Direct Digital Variometer Manual ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pitot-Static System Blockage Effects on Airspeed Indicator

The Dramatic Effects of Pitot-Static System Blockages and Failures by Luiz Roberto Monteiro de Oliveira . Table of Contents I ‐ Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….1 II ‐ Pitot‐Static Instruments…………………………………………………………………………………………..3 III ‐ Blockage Scenarios – Description……………………………..…………………………………….…..…11 IV ‐ Examples of the Blockage Scenarios…………………..……………………………………………….…15 V ‐ Disclaimer………………………………………………………………………………………………………………50 VI ‐ References…………………………………………………………………………………………….…..……..……51 Please also review and understand the disclaimer found at the end of the article before applying the information contained herein. I - Introduction This article takes a comprehensive look into Pitot-static system blockages and failures. These typically affect the airspeed indicator (ASI), vertical speed indicator (VSI) and altimeter. They can also affect the autopilot auto-throttle and other equipment that relies on airspeed and altitude information. There have been several commercial flights, more recently Air France's flight 447, whose crash could have been due, in part, to Pitot-static system issues and pilot reaction. It is plausible that the pilot at the controls could have become confused with the erroneous instrument readings of the airspeed and have unknowingly flown the aircraft out of control resulting in the crash. The goal of this article is to help remove or reduce, through knowledge, the likelihood of at least this one link in the chain of problems that can lead to accidents. Table 1 below is provided to summarize -

Airspeed Indicator Calibration

TECHNICAL GUIDANCE MATERIAL AIRSPEED INDICATOR CALIBRATION This document explains the process of calibration of the airspeed indicator to generate curves to convert indicated airspeed (IAS) to calibrated airspeed (CAS) and has been compiled as reference material only. i Technical Guidance Material BushCat NOSE-WHEEL AND TAIL-DRAGGER FITTED WITH ROTAX 912UL/ULS ENGINE APPROVED QRH PART NUMBER: BCTG-NT-001-000 AIRCRAFT TYPE: CHEETAH – BUSHCAT* DATE OF ISSUE: 18th JUNE 2018 *Refer to the POH for more information on aircraft type. ii For BushCat Nose Wheel and Tail Dragger LSA Issue Number: Date Published: Notable Changes: -001 18/09/2018 Original Section intentionally left blank. iii Table of Contents 1. BACKGROUND ..................................................................................................................... 1 2. DETERMINATION OF INSTRUMENT ERROR FOR YOUR ASI ................................................ 2 3. GENERATING THE IAS-CAS RELATIONSHIP FOR YOUR AIRCRAFT....................................... 5 4. CORRECT ALIGNMENT OF THE PITOT TUBE ....................................................................... 9 APPENDIX A – ASI INSTRUMENT ERROR SHEET ....................................................................... 11 Table of Figures Figure 1 Arrangement of instrument calibration system .......................................................... 3 Figure 2 IAS instrument error sample ........................................................................................ 7 Figure 3 Sample relationship between -

Sept. 12, 1950 W

Sept. 12, 1950 W. ANGST 2,522,337 MACH METER Filed Dec. 9, 1944 2 Sheets-Sheet. INVENTOR. M/2 2.7aar alwg,57. A77OAMA). Sept. 12, 1950 W. ANGST 2,522,337 MACH METER Filed Dec. 9, 1944 2. Sheets-Sheet 2 N 2 2 %/ NYSASSESSN S2,222,W N N22N \ As I, mtRumaIII-m- III It's EARAs i RNSITIE, 2 72/ INVENTOR, M247 aeawosz. "/m2.ATTORNEY. Patented Sept. 12, 1950 2,522,337 UNITED STATES ; :PATENT OFFICE 2,522,337 MACH METER Walter Angst, Manhasset, N. Y., assignor to Square D Company, Detroit, Mich., a corpora tion of Michigan Application December 9, 1944, Serial No. 567,431 3 Claims. (Cl. 73-182). is 2 This invention relates to a Mach meter for air plurality of posts 8. Upon one of the posts 8 are craft for indicating the ratio of the true airspeed mounted a pair of serially connected aneroid cap of the craft to the speed of sound in the medium sules 9 and upon another of the posts 8 is in which the aircraft is traveling and the object mounted a diaphragm capsuler it. The aneroid of the invention is the provision of an instrument s: capsules 9 are sealed and the interior of the cas-l of this type for indicating the Mach number of an . ing is placed in communication with the static aircraft in fight. opening of a Pitot static tube through an opening The maximum safe Mach number of any air in the casing, not shown. The interior of the dia craft is the value of the ratio of true airspeed to phragm capsule is connected through the tub the speed of sound at which the laminar flow of ing 2 to the Pitot or pressure opening of the Pitot air over the wings fails and shock Waves are en static tube through the opening 3 in the back countered. -

Acnmanual.Pdf

Advanced Coastal Navigation Coast Guard Auxiliary Association Inc. Washington, D. C. First Edition..........................................................................1987 Second Edition .....................................................................1990 Third Edition ........................................................................1999 Fourth Edition.......................................................................2002 ii iii iv v vi Advanced Coastal Navigation TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction...................................................................................................ix Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION TO COASTAL NAVIGATION . .1-1 Chapter 2 THE MARINE MAGNETIC COMPASS . .2-1 Chapter 3 THE NAUTICAL CHART . .3-1 Chapter 4 THE NAVIGATOR’S TOOLS & INSTRUMENTS . .4-1 Chapter 5 DEAD RECKONING . .5-1 Chapter 6 PILOTING . .6-1 Chapter 7 CURRENT SAILING . .7-1 Chapter 8 TIDES AND TIDAL CURRENTS . .8-1 Chapter 9 RADIONAVIGATION . .9-1 Chapter 10 NAVIGATION REFERENCE PUBLICATIONS . .10-1 Chapter 11 FUEL AND VOYAGE PLANNING . .11-1 Chapter 12 REFLECTIONS . .12-1 Appendix A GLOSSARY . .A-1 INDEX . .Index-1 vii Advanced Coastal Navigation viii intRodUction WELCOME ABOARD! Welcome to the exciting world of completed the course. But it does marine navigation! This is the fourth require a professional atti tude, care- edition of the text Advanced Coastal ful attention to classroom presenta- Navigation (ACN), designed to be tions, and diligence in working out used in con cert with the 1210-Tr sample problems. chart in the Public Education (PE) The ACN course has been course of the same name taught by designed to utilize the 1210-Tr nau - the United States Coast Guard tical chart. It is suggested that this Auxiliary (USCGAUX). Portions of chart be readily at hand so that you this text are also used for the Basic can follow along as you read the Coastal Navigation (BCN) PE text. We recognize that students course. -

Soaring Weather

Chapter 16 SOARING WEATHER While horse racing may be the "Sport of Kings," of the craft depends on the weather and the skill soaring may be considered the "King of Sports." of the pilot. Forward thrust comes from gliding Soaring bears the relationship to flying that sailing downward relative to the air the same as thrust bears to power boating. Soaring has made notable is developed in a power-off glide by a conven contributions to meteorology. For example, soar tional aircraft. Therefore, to gain or maintain ing pilots have probed thunderstorms and moun altitude, the soaring pilot must rely on upward tain waves with findings that have made flying motion of the air. safer for all pilots. However, soaring is primarily To a sailplane pilot, "lift" means the rate of recreational. climb he can achieve in an up-current, while "sink" A sailplane must have auxiliary power to be denotes his rate of descent in a downdraft or in come airborne such as a winch, a ground tow, or neutral air. "Zero sink" means that upward cur a tow by a powered aircraft. Once the sailcraft is rents are just strong enough to enable him to hold airborne and the tow cable released, performance altitude but not to climb. Sailplanes are highly 171 r efficient machines; a sink rate of a mere 2 feet per second. There is no point in trying to soar until second provides an airspeed of about 40 knots, and weather conditions favor vertical speeds greater a sink rate of 6 feet per second gives an airspeed than the minimum sink rate of the aircraft. -

5.2 Drag Reduction Through Higher Wing Loading David L. Kohlman

5.2 Drag Reduction Through Higher Wing Loading David L. Kohlman University of Kansas |ntroduction The wing typically accounts for almost half of the wetted area of today's production light airplanes and approximately one-third of the total zero-lift or parasite drag. Thus the wing should be a primary focal point of any attempts to reduce drag of light aircraft with the most obvious configuration change being a reduction in wing area. Other possibilities involve changes in thickness, planform, and airfoil section. This paper will briefly discuss the effects of reducing wing area of typical light airplanes, constraints involved, and related configuration changes which may be necessary. Constraints and Benefits The wing area of current light airplanes is determined primarily by stall speed and/or climb performance requirements. Table I summarizes the resulting wing loading for a representative spectrum of single-engine airplanes. The maximum lift coefficient with full flaps, a constraint on wing size, is also listed. Note that wing loading (at maximum gross weight) ranges between about 10 and 20 psf, with most 4-place models averaging between 13 and 17. Maximum lift coefficient with full flaps ranges from 1.49 to 2.15. Clearly if CLmax can be increased, a corresponding decrease in wing area can be permitted with no change in stall speed. If total drag is not increased at climb speed, the change in wing area will not adversely affect climb performance either and cruise drag will be reduced. Though not related to drag, it is worthy of comment that the range of wing loading in Table I tends to produce a rather uncomfortable ride in turbulent air, as every light-plane pilot is well aware. -

FAA Advisory Circular AC 91-74B

U.S. Department Advisory of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration Circular Subject: Pilot Guide: Flight in Icing Conditions Date:10/8/15 AC No: 91-74B Initiated by: AFS-800 Change: This advisory circular (AC) contains updated and additional information for the pilots of airplanes under Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) parts 91, 121, 125, and 135. The purpose of this AC is to provide pilots with a convenient reference guide on the principal factors related to flight in icing conditions and the location of additional information in related publications. As a result of these updates and consolidating of information, AC 91-74A, Pilot Guide: Flight in Icing Conditions, dated December 31, 2007, and AC 91-51A, Effect of Icing on Aircraft Control and Airplane Deice and Anti-Ice Systems, dated July 19, 1996, are cancelled. This AC does not authorize deviations from established company procedures or regulatory requirements. John Barbagallo Deputy Director, Flight Standards Service 10/8/15 AC 91-74B CONTENTS Paragraph Page CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1-1. Purpose ..............................................................................................................................1 1-2. Cancellation ......................................................................................................................1 1-3. Definitions.........................................................................................................................1 1-4. Discussion .........................................................................................................................6 -

Hang Glider: Range Maximization the Problem Is to Compute the flight Inputs to a Hang Glider So As to Provide a Maximum Range flight

Hang Glider: Range Maximization The problem is to compute the flight inputs to a hang glider so as to provide a maximum range flight. This problem first appears in [1]. The hang glider has weight W (glider plus pilot), a lift force L acting perpendicular to its velocity vr relative to the air, and a drag force D acting in a direction opposite to vr. Denote by x the horizontal position of the glider, by vx the horizontal component of the absolute velocity, by y the vertical position, and by vy the vertical component of absolute velocity. The airmass is not static: there is a thermal just 250 meters ahead. The profile of the thermal is given by the following upward wind velocity: 2 2 − x −2.5 x u (x) = u e ( R ) 1 − − 2.5 . a m R We take R = 100 m and um = 2.5 m/s. Note, MKS units are used through- out. The upwind profile is shown in Figure 1. Letting η denote the angle between vr and the horizontal plane, we have the following equations of motion: 1 x˙ = vx, v˙x = m (−L sin η − D cos η), 1 y˙ = vy, v˙y = m (L cos η − D sin η − W ) with q vy − ua(x) 2 2 η = arctan , vr = vx + (vy − ua(x)) , vx 1 1 L = c ρSv2,D = c (c )ρSv2,W = mg. 2 L r 2 D L r The glider is controlled by the lift coefficient cL. The drag coefficient is assumed to depend on the lift coefficient as 2 cD(cL) = c0 + kcL where c0 = 0.034 and k = 0.069662. -

Module-7 Lecture-29 Flight Experiment

Module-7 Lecture-29 Flight Experiment: Instruments used in flight experiment, pre and post flight measurement of aircraft c.g. Module Agenda • Instruments used in flight experiments. • Pre and post flight measurement of center of gravity. • Experimental procedure for the following experiments. (a) Cruise Performance: Estimation of profile Drag coefficient (CDo ) and Os- walds efficiency (e) of an aircraft from experimental data obtained during steady and level flight. (b) Climb Performance: Estimation of Rate of Climb RC and Absolute and Service Ceiling from experimental data obtained during steady climb flight (c) Estimation of stick free and fixed neutral and maneuvering point using flight data. (d) Static lateral-directional stability tests. (e) Phugoid demonstration (f) Dutch roll demonstration 1 Instruments used for experiments1 1. Airspeed Indicator: The airspeed indicator shows the aircraft's speed (usually in knots ) relative to the surrounding air. It works by measuring the ram-air pressure in the aircraft's Pitot tube. The indicated airspeed must be corrected for air density (which varies with altitude, temperature and humidity) in order to obtain the true airspeed, and for wind conditions in order to obtain the speed over the ground. 2. Attitude Indicator: The attitude indicator (also known as an artificial horizon) shows the aircraft's relation to the horizon. From this the pilot can tell whether the wings are level and if the aircraft nose is pointing above or below the horizon. This is a primary instrument for instrument flight and is also useful in conditions of poor visibility. Pilots are trained to use other instruments in combination should this instrument or its power fail. -

How to Make My Air Glide S Work Properly

How to make my Air Glide S work properly Originally written by Horst Rupp. Many thanks to Richard Frawley who edited and retranslated this article into proper English. 2014/11/21. The basic prerequisite for the Air Glide S, in particular the AHRS part, to work properly so that the extraneous ‘noise’ (gusts, wind shifts, perturbations etc) can be removed is to ensure that it is set up correctly. The instrument is very sensitive and the installation needs to be done in a way that ensures that only the correct inputs are being sensed. Most legacy instrument installations take all pressures from probes at the rudder fin. And most unfortunately, many of them use the total energy (TE) pressure from the fin to feed in parallel a mass-measurement variometer with a capacity flask (in Germany mostly a Winter) and a pressure sensor probe variometer such as the Air Glide S (no capacity flask). There are many publications indicating the deterioration (mostly damping) of the pressure sensor probe measurements by the stream of air mass in and out of the capacity flask. So, it is obviously a somewhat bad idea to do that to your Air Glide S. This interference with a mass measuring instruments is certainly not compliant with the above mentioned basic prerequisite. Fortunately, the Air Glide S can be compensated by total pressure (called electronic compensation as opposed to TE compensation). This is a new feature of the Air Glide S arriving with V 1.1. Total pressure and TE pressure carry more or less (depends on quality of probe) the same information - but for the sign : Total pressure is static pressure PLUS pitot pressure, TE pressure is static pressure MINUS pitot pressure (probe compensation factor (~)-1). -

Subsonic Aircraft Wing Conceptual Design Synthesis and Analysis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by GSSRR.ORG: International Journals: Publishing Research Papers in all Fields International Journal of Sciences: Basic and Applied Research (IJSBAR) ISSN 2307-4531 (Print & Online) http://gssrr.org/index.php?journal=JournalOfBasicAndApplied --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Subsonic Aircraft Wing Conceptual Design Synthesis and Analysis Abderrahmane BADIS Electrical and Electronic Communication Engineer from UMBB (Ex.INELEC) Independent Electronics, Aeronautics, Propulsion, Well Logging and Software Design Research Engineer Takerboust, Aghbalou, Bouira 10007, Algeria [email protected] Abstract This paper exposes a simplified preliminary conceptual integrated method to design an aircraft wing in subsonic speeds up to Mach 0.85. The proposed approach is integrated, as it allows an early estimation of main aircraft aerodynamic features, namely the maximum lift-to-drag ratio and the total parasitic drag. First, the influence of the Lift and Load scatterings on the overall performance characteristics of the wing are discussed. It is established that the optimization is achieved by designing a wing geometry that yields elliptical lift and load distributions. Second, the reference trapezoidal wing is considered the base line geometry used to outline the wing shape layout. As such, the main geometrical parameters and governing relations for a trapezoidal wing are -

F—18 Navy Air Combat Fighter

74 /2 >Af ^y - Senate H e a r tn ^ f^ n 12]$ Before the Committee on Appro priations (,() \ ER WIIA Storage ime nts F EB 1 2 « T H e -,M<rUN‘U«sni KAN S A S S F—18 Na vy Air Com bat Fighter Fiscal Year 1976 th CONGRESS, FIRS T SES SION H .R . 986 1 SPECIAL HEARING F - 1 8 NA VY AIR CO MBA T FIG H TER HEARING BEFORE A SUBC OMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE NIN ETY-FOURTH CONGRESS FIR ST SE SS IO N ON H .R . 9 8 6 1 AN ACT MAKIN G APP ROPR IA TIO NS FO R THE DEP ARTM EN T OF D EFEN SE FO R T H E FI SC AL YEA R EN DI NG JU N E 30, 1976, AND TH E PE RIO D BE GIN NIN G JU LY 1, 1976, AN D EN DI NG SEPT EM BER 30, 1976, AND FO R OTH ER PU RP OSE S P ri nte d fo r th e use of th e Com mittee on App ro pr ia tio ns SPECIAL HEARING U.S. GOVERNM ENT PRINT ING OFF ICE 60-913 O WASHINGTON : 1976 SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS JOHN L. MCCLELLAN, Ark ans as, Chairman JOH N C. ST ENN IS, Mississippi MILTON R. YOUNG, No rth D ako ta JOH N O. P ASTORE, Rhode Island ROMAN L. HRUSKA, N ebraska WARREN G. MAGNUSON, Washin gton CLIFFORD I’. CASE, New Je rse y MIK E MANSFIEL D, Montana HIRAM L.