Oversight Hearing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pcbs : 465 in 1 Babystar PCB

PCBs : 465 in 1 BabyStar PCB 465 in 1 BabyStar PCB 465 in 1 BabyStar PCB 465 Games in 1 BabyStar PCB Rating: Not Rated Yet Price: Sales price: $274.95 Discount: Ask a question about this product Description 465 in 1 BabyStar PCB ***ATX Power Supply with P4 connector required for operation*** JAMMA ready arcade system containing 465 vertical ready to play games. Choose from classics like Ms. Pac man, Donkey Kong, and Frogger to great shooters like 19XX, Strikers 1945 II, and Varth! The game selection menu is easy to understand and navigate. To select a game, scroll through the list and press your button to select. At anytime during the active game aplayer can return back to main game selection menu by holding in the start button for 3 seconds. This sytem runs on a stable flash drive. No hard drive to ever fail! Supports Vertically mounted monitors only. Universal JAMMA Connector. User Friendly Game Selection Screen. P4 Motherboard using genuine Intel Processor and Card Flash memory creates a faster/more stable system! User Adjustable Game Options (Game Dip Switch Settings; Number of Lives, Difficulty, etc). Supports 1-4 Player Games (players 3 & 4 via linking - kit included). Supports two-channel audio (Stereo Sound). Supports CGA Standard Arcade Monitor (15kHz). Supports Upright Cabinets (will not flip screen for cocktails). Enable One Game (for a dedicated machine if desired) or All Games. Enable/Disable Individual Game Categories From Showing. Delete/Undelete Each Game. Set Coin/Credit Ratio of All Games with One Setting. Supports a Coin Counter. System Specifications: JAMMA Controller/Interface PCB. -

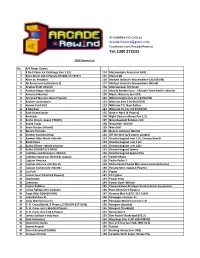

Arcade Rewind 3500 Games List 190818.Xlsx

ArcadeRewind.com.au [email protected] Facebook.com/ArcadeRewind Tel: 1300 272233 3500 Games List No. 3/4 Player Games 1 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 114 Metamorphic Force (ver EAA) 2 Alien Storm (US,3 Players,FD1094 317-0147) 115 Mexico 86 3 Alien vs. Predator 116 Michael Jackson's Moonwalker (US,FD1094) 4 All American Football (rev E) 117 Michael Jackson's Moonwalker (World) 5 Arabian Fight (World) 118 Minesweeper (4-Player) 6 Arabian Magic <World> 119 Muscle Bomber Duo - Ultimate Team Battle <World> 7 Armored Warriors 120 Mystic Warriors (ver EAA) 8 Armored Warriors (Euro Phoenix) 121 NBA Hangtime (rev L1.1 04/16/96) 9 Asylum <prototype> 122 NBA Jam (rev 3.01 04/07/93) 10 Atomic Punk (US) 123 NBA Jam T.E. Nani Edition 11 B.Rap Boys 124 NBA Jam TE (rev 4.0 03/23/94) 12 Back Street Soccer 125 Neck-n-Neck (4 Players) 13 Barricade 126 Night Slashers (Korea Rev 1.3) 14 Battle Circuit <Japan 970319> 127 Ninja Baseball Batman <US> 15 Battle Toads 128 Ninja Kids <World> 16 Beast Busters (World) 129 Nitro Ball 17 Blazing Tornado 130 Numan Athletics (World) 18 Bomber Lord (bootleg) 131 Off the Wall (2/3-player upright) 19 Bomber Man World <World> 132 Oriental Legend <ver.112, Chinese Board> 20 Brute Force 133 Oriental Legend <ver.112> 21 Bucky O'Hare <World version> 134 Oriental Legend <ver.126> 22 Bullet (FD1094 317-0041) 135 Oriental Legend Special 23 Cadillacs and Dinosaurs <World> 136 Oriental Legend Special Plus 24 Cadillacs Kyouryuu-Shinseiki <Japan> 137 Paddle Mania 25 Captain America 138 Pasha Pasha 2 26 Captain America -

Download 80 PLUS 4983 Horizontal Game List

4 player + 4983 Horizontal 10-Yard Fight (Japan) advmame 2P 10-Yard Fight (USA, Europe) nintendo 1941 - Counter Attack (Japan) supergrafx 1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) mame172 2P sim 1942 (Japan, USA) nintendo 1942 (set 1) advmame 2P alt 1943 Kai (Japan) pcengine 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) mame172 2P sim 1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) mame172 2P sim 1943 - The Battle of Midway (USA) nintendo 1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) mame172 2P sim 1945k III advmame 2P sim 19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) mame172 2P sim 2010 - The Graphic Action Game (USA, Europe) colecovision 2020 Super Baseball (set 1) fba 2P sim 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) mame078 4P sim 36 Great Holes Starring Fred Couples (JU) (32X) [!] sega32x 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex (NGM-043)(NGH-043) fba 2P sim 3D Crazy Coaster vectrex 3D Mine Storm vectrex 3D Narrow Escape vectrex 3-D WorldRunner (USA) nintendo 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) [!] megadrive 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) supernintendo 4-D Warriors advmame 2P alt 4 Fun in 1 advmame 2P alt 4 Player Bowling Alley advmame 4P alt 600 advmame 2P alt 64th. Street - A Detective Story (World) advmame 2P sim 688 Attack Sub (UE) [!] megadrive 720 Degrees (rev 4) advmame 2P alt 720 Degrees (USA) nintendo 7th Saga supernintendo 800 Fathoms mame172 2P alt '88 Games mame172 4P alt / 2P sim 8 Eyes (USA) nintendo '99: The Last War advmame 2P alt AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (E) [!] supernintendo AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (UE) [!] megadrive Abadox - The Deadly Inner War (USA) nintendo A.B. -

The Use of Copyright Laws to Prevent the Importation of Genuine Goods

NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW Volume 11 Number 2 Article 3 Spring 1986 The Use of Copyright Laws to Prevent the Importation of Genuine Goods James P. Donohue Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj Part of the Commercial Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation James P. Donohue, The Use of Copyright Laws to Prevent the Importation of Genuine Goods, 11 N.C. J. INT'L L. 183 (1986). Available at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol11/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Use of Copyright Laws To Prevent the Importation of "Genuine Goods" James P. Donohue* I. Introduction United States subsidiaries or affiliates of foreign corporations' and U.S. companies with foreign subsidiaries2 find their domestic distribution networks increasingly threatened by the unauthorized importation of goods substantially similar to the goods they market. The imported goods are intended to be marketed abroad, but are instead imported into the United States and sold in competition with established U.S. distribution networks. This practice is referred to as 3 "parallel importation" or "diversion."' 4 The imports, so-called "genuine goods," 5 are often referred to as "grey market" goods. 6 The primary reason for the success of grey market distributors is their ability to offer the same goods at prices lower than those de- manded by U.S. -

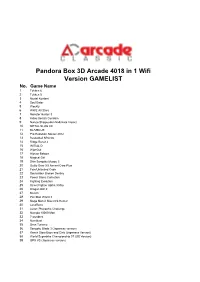

Pandora Box 3D Arcade 4018 in 1 Wifi Version GAMELIST No

Pandora Box 3D Arcade 4018 in 1 Wifi Version GAMELIST No. Game Name 1 Tekken 6 2 Tekken 5 3 Mortal Kombat 4 Soul Eater 5 Weekly 6 WWE All Stars 7 Monster Hunter 3 8 Kidou Senshi Gundam 9 Naruto Shippuuden Naltimate Impact 10 METAL SLUG XX 11 BLAZBLUE 12 Pro Evolution Soccer 2012 13 Basketball NBA 06 14 Ridge Racer 2 15 INITIAL D 16 WipeOut 17 Hitman Reborn 18 Magical Girl 19 Shin Sangoku Musou 5 20 Guilty Gear XX Accent Core Plus 21 Fate/Unlimited Code 22 Soulcalibur Broken Destiny 23 Power Stone Collection 24 Fighting Evolution 25 Street Fighter Alpha 3 Max 26 Dragon Ball Z 27 Bleach 28 Pac Man World 3 29 Mega Man X Maverick Hunter 30 LocoRoco 31 Luxor: Pharaoh's Challenge 32 Numpla 10000-Mon 33 7 wonders 34 Numblast 35 Gran Turismo 36 Sengoku Blade 3 (Japanese version) 37 Ranch Story Boys and Girls (Japanese Version) 38 World Superbike Championship 07 (US Version) 39 GPX VS (Japanese version) 40 Super Bubble Dragon (European Version) 41 Strike 1945 PLUS (US version) 42 Element Monster TD (Chinese Version) 43 Ranch Story Honey Village (Chinese Version) 44 Tianxiang Tieqiao (Chinese version) 45 Energy gemstone (European version) 46 Turtledove (Chinese version) 47 Cartoon hero VS Capcom 2 (American version) 48 Death or Life 2 (American Version) 49 VR Soldier Group 3 (European version) 50 Street Fighter Alpha 3 51 Street Fighter EX 52 Bloody Roar 2 53 Tekken 3 54 Tekken 2 55 Tekken 56 Mortal Kombat 4 57 Mortal Kombat 3 58 Mortal Kombat 2 59 The overlord continent 60 Oda Nobunaga 61 Super kitten 62 The battle of steel benevolence 63 Mech -

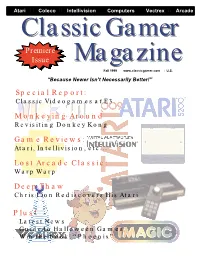

Premiere Issue Monkeying Around Game Reviews: Special Report

Atari Coleco Intellivision Computers Vectrex Arcade ClassicClassic GamerGamer Premiere Issue MagazineMagazine Fall 1999 www.classicgamer.com U.S. “Because Newer Isn’t Necessarily Better!” Special Report: Classic Videogames at E3 Monkeying Around Revisiting Donkey Kong Game Reviews: Atari, Intellivision, etc... Lost Arcade Classic: Warp Warp Deep Thaw Chris Lion Rediscovers His Atari Plus! · Latest News · Guide to Halloween Games · Win the book, “Phoenix” “As long as you enjoy the system you own and the software made for it, there’s no reason to mothball your equipment just because its manufacturer’s stock dropped.” - Arnie Katz, Editor of Electronic Games Magazine, 1984 Classic Gamer Magazine Fall 1999 3 Volume 1, Version 1.2 Fall 1999 PUBLISHER/EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Chris Cavanaugh - [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Sarah Thomas - [email protected] STAFF WRITERS Kyle Snyder- [email protected] Reset! 5 Chris Lion - [email protected] Patrick Wong - [email protected] Raves ‘N Rants — Letters from our readers 6 Darryl Guenther - [email protected] Mike Genova - [email protected] Classic Gamer Newswire — All the latest news 8 Damien Quicksilver [email protected] Frank Traut - [email protected] Lee Seitz - [email protected] Book Bytes - Joystick Nation 12 LAYOUT/DESIGN Classic Advertisement — Arcadia Supercharger 14 Chris Cavanaugh PHOTO CREDITS Atari 5200 15 Sarah Thomas - Staff Photographer Pong Machine scan (page 3) courtesy The “New” Classic Gamer — Opinion Column 16 Sean Kelly - Digital Press CD-ROM BIRA BIRA Photos courtesy Robert Batina Lost Arcade Classics — ”Warp Warp” 17 CONTACT INFORMATION Classic Gamer Magazine Focus on Intellivision Cartridge Reviews 18 7770 Regents Road #113-293 San Diego, Ca 92122 Doin’ The Donkey Kong — A closer look at our 20 e-mail: [email protected] on the web: favorite monkey http://www.classicgamer.com Atari 2600 Cartridge Reviews 23 SPECIAL THANKS To Sarah. -

Game List of Game Elf (Vertical) 001.Ms

Game list of game elf (Vertical) 001.Ms. Pac-Man ▲ 044.Arkanoid 002.Ms. Pac-Man (speedup) 045.Super Qix 003.Ms. Pac-Man Plus 046.Juno First 004.Galaga 047.Xevious 005.Frogger 048.Mr. Do's Castle 006.Frog 049.Moon Cresta 007.Donkey Kong 050.Pinball Action 008.Crazy Kong 051.Scramble 009.Donkey Kong Junior 052.Super Pac-Man 010.Donkey Kong 3 053.Bomb Jack 011.Galaxian 054.Shao-Lin's Road 012.Galaxian Part X 055.King & Balloon 013.Galaxian Turbo ▲ 56.1943 014.Dig Dug 057.Van-Van Car 015.Crush Roller 058.Pac-Man Plus 016.Mr. Do! 059.Pac & Pal 017.Space Invaders Part II 060.Dig Dug II 018.Super Invaders (EMAG) 061.Amidar 019.Return of the Invaders 062.Zaxxon ▲ 020.Super Space Invaders '91 063.Super Zaxxon 021.Pac-Man 064.Pooyan 022.PuckMan ▲ 065.Pleiads 023.PuckMan (speedup) 066.Gun.Smoke 024.New Puck-X 067.The End 025.Newpuc2 ▲ 068.1943 Kai 026.Galaga 3 069.Congo Bongo 027.Gyruss 070.Jumping Jack 028.Tank Battalion 071.Big Kong 29.1942 072.Bongo 030.Lady Bug 073.Gaplus 031.Burger Time 074.Ms. Pac Attack 032.Mappy 075.Abscam 033.Centipede 076.Ajax ▲ 034.Millipede 077.Ali Baba and 40 Thieves 035.Jr. Pac-Man ▲ 078.Finalizer - Super Transformation 036.Pengo 079.Arabian 037.Son of Phoenix 080.Armored Car 038.Time Pilot 081.Astro Blaster 039.Super Cobra 082.Astro Fighter 040.Video Hustler 083.Astro Invader 041.Space Panic 084.Battle Lane! 042.Space Panic (harder) 085.Battle-Road, The ▲ 043.Super Breakout 086.Beastie Feastie Caution: ▲ No flipped screen’s games ! 1 Game list of game elf (Vertical) 087.Bio Attack 130.Go Go Mr. -

COCKTAIL 287IN1) 1 Frogger 48 Chopper I (US Set 3) 2 Galaga 3 (Rev

Game list of CF (COCKTAIL 287IN1) 1 Frogger 48 Chopper I (US set 3) 2 Galaga 3 (rev. C) 49 Circus Charlie (Centuri) 3 Galaga (Namco rev. B) 50 Circus Charlie (Centuri, earlier) 4 Gyruss (Konami) 51 Crazy Kong (set 1) 5 Lady Bug 52 Crazy Kong (set 2) 6 Burger Time (Data East set 1) 53 Crazy Kong (Alca bootleg) 7 Centipede (revision 3) 54 Crazy Kong (Jeutel bootleg) 8 Jr. Pac-Man 55 Crazy Kong (Orca bootleg) 9 Space Panic (version E) 56 Crazy Kong (Scramble hardware) 10 New Rally X 57 Senjou no Ookami 11 Van-Van Car 58 Commando (World) 12 King & Balloon (US) 59 Commando (US) 13 Mr. Do's Castle (set 1) 60 Congo Bongo 14 Juno First 61 Contra (US) 15 Ms. Pac-Man 62 Contra (Japan) 16 Gaplus (rev. D) 63 Daisenpu (Japan) 17 Eight Ball Action (DK conversion) 64 Dangar - Ufo Robo (12/1/1986) 18 Eight Ball Action (DKJr conversion) 65 Dangar - Ufo Robo (9/26/1986) 19 '99: The Last War 66 Dangar - Ufo Robo (bootleg) 20 '99: The Last War (alternate) 67 Darwin 4078 (Japan) 21 Ajax 68 Devil Fish (Galaxian hardware, bootleg?) 22 Ajax (Japan) 69 Devil Fish 23 Alphax Z, The (Japan) 70 Dig Dug II (New Ver.) 24 Sei Senshi Amatelass 71 Dig Dug II (Old Ver.) 25 Soldier Girl Amazon 72 Donkey Kong Junior (bootleg?) 26 Argus 73 Donkey Kong Junior (Japan?) 27 Armed Formation 74 Donkey Kong (US set 1) 28 Bagman 75 Donkey Kong 3 (US) Donkey Kong 3 (bootleg on Donkey Kong Jr. -

3500-Arcadegamelist.Pdf

No. GameName PlayersGroup 1 10 Yard Fight <Japan> Sport 2 1000 Miglia:Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) Driving 3 18 Challenge Pro Golf (DECO,Japan) Sport 4 18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) Sport 5 1941:Counter Attack (World 900227) Shoot 6 1942 (Revision B) Shoot 7 1943 Kai:Midway Kaisen (Japan) Shoot 8 1943:The Battle of Midway (Euro) Shoot 9 1944:The Loop Master (USA 000620) Shoot 10 1945k III (newer, OPCX2 PCB) Shoot 11 19XX:The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) Shoot 12 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge 3/4P Sport 13 2020 Super Baseball <set 1> Sport 14 3 Count Bout/Fire Suplex Fighter 15 3D_Aqua Rush (JP) Ver. A Maze 16 3D_Battle Arena Toshinden 2 Fighter 17 3D_Beastorizer (US) Fighter 18 3D_Beastorizer <US *bootleg*> Fighter 19 3D_Bloody Roar 2 <Japan> Fighter 20 3D_Brave Blade <Japan> Fighter 21 3D_Cool Boarders Arcade Jam (US) Sport 22 3D_Dancing Eyes <Japan ver.A> Adult 23 3D_Dead or Alive++ Fighter 24 3D_Ehrgeiz (US) Ver. A Fighter 25 3D_Fighters Impact A (JP 2.00J) Fighter 26 3D_Fighting Layer (JP) Ver.B Fighter 27 3D_Gallop Racer 3 (JP) Sport 28 3D_G-Darius (JP 2.01J) Sport 29 3D_G-Darius Ver.2 (JP 2.03J) Sport 30 3D_Heaven's Gate Fighter 31 3D_Justice Gakuen (JP 991117) Fighter 32 3D_Kikaioh (JP 980914) Fighter 33 3D_Kosodate Quiz My Angel 3 (JP) Ver.A Maze 34 3D_Magical Date EX (JP 2.01J) Maze 35 3D_Monster Farm Jump (JP) Maze 36 3D_Mr Driller (JP) Ver.A Maze 37 3D_Paca Paca Passion (JP) Ver.A Maze 38 3D_Plasma Sword (US 980316) Fighter 39 3D_Prime Goal EX (JP) Sport 40 3D_Psychic Force (JP 2.4J) Fighter 41 3D_Psychic Force (World 2.4O) Fighter 42 3D_Psychic Force EX (JP 2.0J) Fighter 43 3D_Raystorm (JP 2.05J) Shoot 44 3D_Raystorm (US 2.06A) Shoot 45 3D_Rival Schools (ASIA 971117) Fighter 46 3D_Rival Schools <US 971117> Fighter 47 3D_Shanghai Matekibuyuu (JP) Maze 48 3D_Sonic Wings Limited <Japan> Shoot 49 3D_Soul Edge (JP) SO3 Ver. -

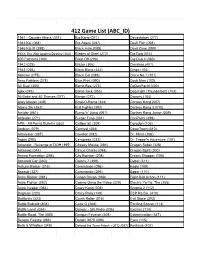

PRINT 412 Gamelist Abc(ID).Xlsx

412 Game List (ABC_ID) 1941 - Counter Attack (351) Big Kong (071) Devastators (277) 1943 Kai (068) Bio Attack (087) Devil Fish (098) 1945 Kai III (398) Black Hole (088) Devil Zone (099) 19XX:The War Against Destiny (384) Blades of Steel (272) Dig Dug (014) 800 Fathoms (160) Blast Off (293) Dig Dug II (060) 1942 (029) Blazer (306) Dimahoo (401) 1943 (056) Block Block (342) Dingo (100) Abscam (075) Block Gal (089) Disco No.1 (101) Aero Fighters (278) Blue Print (090) Dock Man (102) Air Duel (305) Bomb Bee (273) DoDonPachi (400) Ajax (076) Bomb Jack (053) Dog Fight (Thunderbolt) (103) Ali Baba and 40 Thieves (077) Bongo (072) Dommy (104) Alley Master (339) Bowl-O-Rama (344) Donkey Kong (007) Alpine Ski (352) Bull Fighter (392) Donkey Kong 3 (010) Amidar (061) Bump 'n' Jump (091) Donkey Kong Junior (009) Anteater (271) Burger Time (031) DonPachi (399) APB - All Points Bulletin (353) Caliber 50 (309) Dorodon (105) Arabian (079) Carnival (354) DownTown (310) Arbalester (397) Cavelon (092) Dr. Micro (106) Argus (290) Centipede (033) Dr. Toppel's Adventure (107) Arkanoid - Revenge of DOH (395) Cheeky Mouse (093) Dragon Saber (328) Arkanoid (044) Circus Charlie (094) Dragon Spirit (300) Armed Formation (298) City Bomber (208) Dream Shopper (108) Armored Car (080) Colony 7 (389) Dyger (311) Ashura Blaster (316) Commando (095) Eagle (109) Assault (327) Commando (299) Eggor (110) Astro Blaster (081) Congo Bongo (069) Eight Ball Action (111) Astro Fighter (082) Cosmo Gang the Video (329) Electric Yo-Yo, The (355) Astro Invader (083) Crazy Kong (008) Enigma 2 (112) Bagman (220) Crazy Rally (148) ESP Ra.De. -

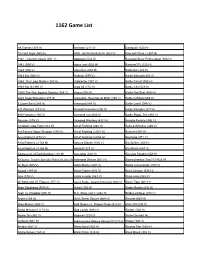

1162 Game List

1162 Game List '88 Games (381 H) Anteater (271 V) Baraduke (543 H) 10-Yard Fight (540 H) APB - All Points Bulletin (353 V) Baseball Stars 2 (367 H) 1941 - Counter Attack (351 V) Appoooh (542 H) Baseball Stars Professional (366 H) 1942 (029 V) Aqua Jack (653 H) Batman(1P) (125 H) 1943 (056 V) Aquarium (654 H) Battlantis (323 V) 1943 Kai (068 V) Arabian (079 V) Battle Bakraid (408 V) 1944: The Loop Master (167 H) Arbalester (397 V) Battle Circuit (088 H) 1945 Kai III (398 V) Area 88 (172 H) Battle City (528 H) 19XX:The War Against Destiny (384 V) Argus (290 V) Battle Flip Shot (405 H) 2020 Super Baseball (375 H) Arkanoid - Revenge of DOH (395 V) Battle K-Road (669 H) 3 Count Bout (243 H) Arkanoid (044 V) Battle Lane! (084 V) 4-D Warriors (191 H) Armed Formation (298 V) Battle Rangers (317 H) 800 Fathoms (160 V) Armored Car (080 V) Battle-Road, The (085 V) Abscam (075 V) Armored Warriors (432 H) Beastie Feastie (086 V) Acrobatic Dog-Fight (533 H) Art of Fighting (050 H) Bells & Whistles (349 V) Act-Fancer Hyper Weapon (318 H) Art of Fighting 2 (051 H) Berzerk (495 H) Aero Fighters (278 V) Art of Fighting 3 (052 H) Big Kong (071 V) Aero Fighters 2 (163 H) Ashura Blaster (316 V) Big Striker (360 H) Aero Fighters 3 (164 H) Assault (327 V) Bio Attack (087 V) Aggressors of Dark Kombat (116 H) Asteroids (620 H) Bio-ship Paladin (658 H) Air Buster: Trouble Specialty Raid Unit (652 H) Asteroids Deluxe (621 H) Biomechanical Toy(1P) (428 H) Air Duel (305 V) Astro Blaster (081 V) Bionic Commando (310 H) Airwolf (189 H) Astro Fighter (082 V) Black Dragon (536 H) Ajax (076 V) Astro Invader (083 V) Black Hole (088 V) Ali Baba and 40 Thieves (077 V) Asura Blade - Sword of Dynasty (655 H) Black Tiger (661 H) Alien Syndrome (515 H) Aurail (152 H) Blade Master (032 H) Alien vs. -

Games Family 3000 in 1

Games Family 3000 in 1 1 10 Yard Fight <Japan> 1480 Mega Zone <Konami set 1> 2 1941 1481 Megadon 3 1941 Counter Attack <Japan> 1482 Megatack 4 1942 1483 Meikyu Jima <Japan> 5 1942 <set 2> 1484 Meikyuu Hunter G <Japan> 6 1942 <set 3> 1485 Mello Yello Q*bert 7 1943 1486 Mercs <US 900608> 8 1943: Midway Kaisen <Japan> 1487 Mercs <US> 9 1943kai 1488 Mercs <World> 10 1944 1489 Merlins Money Maze 11 1945 1490 Meta Fox 12 1945k III 1491 Metal Black <Japan> 13 1945Plus 1492 Metal Black <World> 14 19xx 1493 Metal Clash <Japan> 15 19XX: The War Against Destiny <Asia 951207> 1494 Metal Slug Super Vehicle001 16 19XX: The War Against Destiny <Hispanic 951218> 1495 Metal Slug 2 Super Vehicle001/II 17 19XX: The War Against Destiny <Japan 951207> 1496 Metal Slug 3 18 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge <rev 1.21> 1497 Metal Slug 3 <not encrypted> 19 2020 Super Baseball <set 1> 1498 Metal Slug 4 20 2020 Super Baseball <set 2> 1499 Metal Slug 4 Plus 21 2020 Super Baseball <set 3> 1500 Metal Slug 4 Plus <bootleg> 22 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex 1501 Metal Slug 5 23 3D Battle Arena Toshinden 2 (JP) 1502 Metal Slug 6 24 3D Battle Arena Toshinden 2 (US) 1503 Metal Slug X Super Vehicle001 25 3D Beastorizer<US> 1504 Metamoqester 26 3D Bloody Roar 2 1505 Meteorites 27 3D Brave Blade 1506 MetroCross <set 2> 28 3D Plasma Sword (US) 1507 MetroCross<set 1> 29 3D Rival Schools (US) 1508 Mexico 86 30 3D Sonic Wings Limited 1509 Michael Jackson's Moonwalker <bootleg> 31 3D Soul Edge Ver.