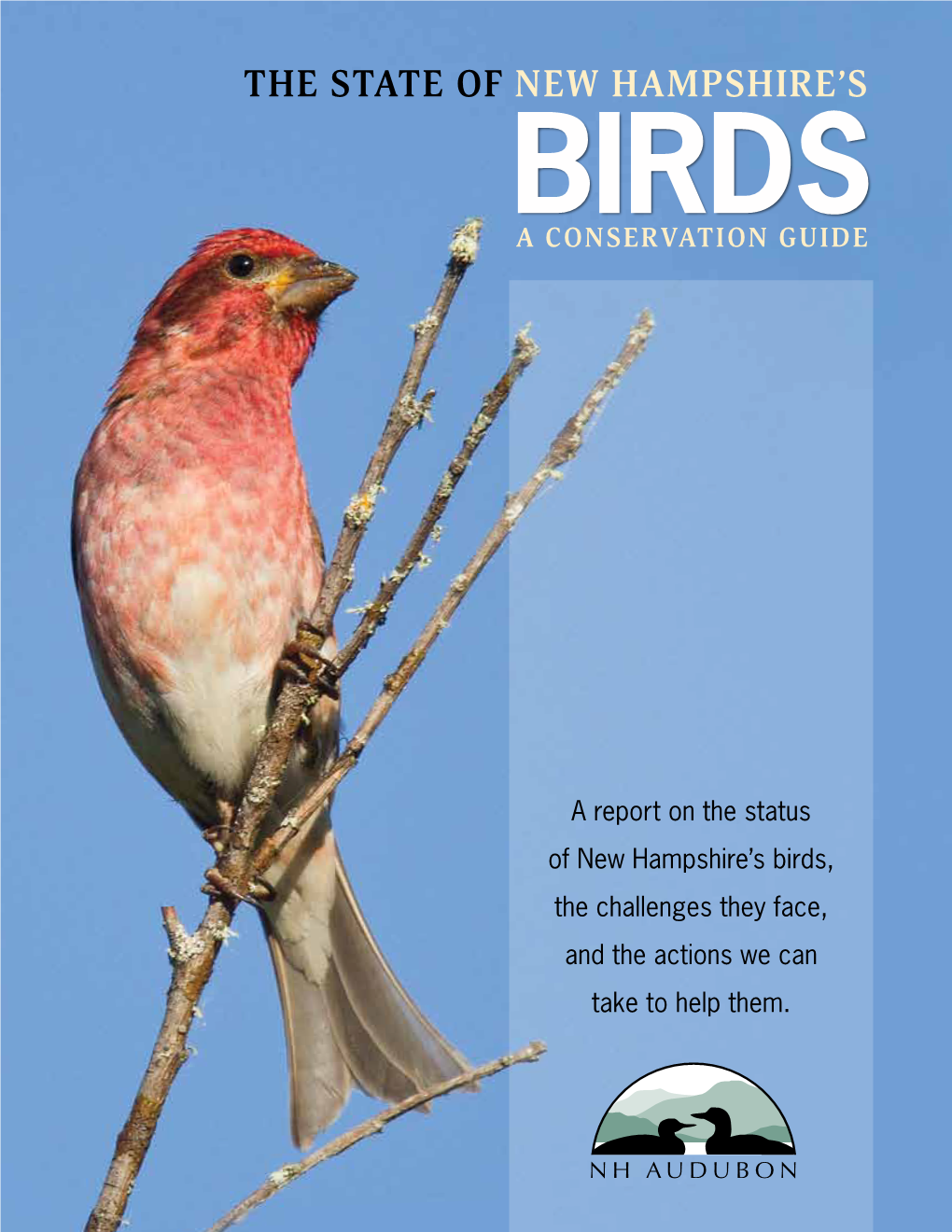

State of New Hampshire's Birds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Oxbow Philadelphia Vireo

The Oxbow Philadelphia Vireo Ron Lockwood In 1998 a Philadelphia Vireo {Vireo philadelphicus) was present during the spring and summer months in the Oxbow National Wildlife Refuge in Harvard, an occurrence that was unusual since Harvard is well south of the region where this vireo species normally breeds. In the spring of 1999, a Philadelphia Vireo, possibly the same individual that was observed in 1998, was again present from the middle of May until at least August. In 1999, however, the vireo sang a song that was similar to the song of the Warbling Vireos {Vireo gilvus) that commonly breed along the Nashua River. It sang this aberrant song, as well as the normal Philadelphia Vireo song, for about the first month after arriving. Later in the summer it sang the normal Philadelphia Vireo song exclusively. Except for a mimid or starling, this was the first time I had heard an individual of one passerine species sing the song of another. To my ear, the aberrant song sounded very much like an abbreviated Warbling Vireo song, but sweeter and not quite so throaty. Upon careful observation, the bird’s plumage was consistent with that of a typical Philadelphia Vireo with dark lores, a yellow breast, a slightly less bright yellow belly and undertail coverts, and a gray crown grading into an olive nape and back. There was no visual indication that the vireo was a hybrid. Bird song serves multiple functions including the establishment and maintenance of breeding and feeding territories, and mate attraction (e.g., Kroodsma and Byers 1991; McDonald 1989). -

PHVI-2020-10-Byrne Copy

PHVI-2020-10 (Philadelphia Vireo) 1st round voting – December 6, 2020 Accepted: 8 Not Accepted: 1 black lores, yellow throat and undertail coverts rule out Warbling Vireo Although the photos submitted by Diane to the committee are decent and definitely adequate, Steve Kornfeld’s photos on eBird leave absolutely no doubt as to the ID (https://ebird.org/checklist/S74131980). The dark lores and yellowish ventrum, especially on the throat and upper breast, are conclusive, and eliminate any similar vireo species, especially a Warbling Vireo. Warbling vireo is eliminated based on dark lores and more yellow on undersides, Red-eyed vireo is eliminated based on smaller bill and lack of upper dark line to eyebrow. No comments There are better photos on eBird, too. The dark lores, compact shape, dark cap, and yellow upper breast all look good for Philly. Can't believe this was a first for the Oregon coast! I think I’m satisfied that the photos confirm this to be a Phillie Vireo. In an ideal world it would be nice to see the bird at additional angles, but from what we can see of the face in the two shots, particularly the dark line through the lore and eye, it appears to be wholly consistent with Phillie Vireo and not a good match for Warbling (or Red-eyed). Tennessee Warbler is, of course, the other species to be careful of, but the bird in Diana’s photos shows yellow undertail coverts as well as a yellow wash across the breast, whereas Tennessee should have whiter undertail coverts. -

Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers

Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Brandan L. Gray August 2019 © 2019 Brandan L. Gray. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers by BRANDAN L. GRAY has been approved for the Department of Biological Sciences and the College of Arts and Sciences by Donald B. Miles Professor of Biological Sciences Florenz Plassmann Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT GRAY, BRANDAN L., Ph.D., August 2019, Biological Sciences Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers Director of Dissertation: Donald B. Miles In a rapidly changing world, species are faced with habitat alteration, changing climate and weather patterns, changing community interactions, novel resources, novel dangers, and a host of other natural and anthropogenic challenges. Conservationists endeavor to understand how changing ecology will impact local populations and local communities so efforts and funds can be allocated to those taxa/ecosystems exhibiting the greatest need. Ecological morphological and functional morphological research form the foundation of our understanding of selection-driven morphological evolution. Studies which identify and describe ecomorphological or functional morphological relationships will improve our fundamental understanding of how taxa respond to ecological selective pressures and will improve our ability to identify and conserve those aspects of nature unable to cope with rapid change. The New World wood warblers (family Parulidae) exhibit extensive taxonomic, behavioral, ecological, and morphological variation. -

Avian Predation in a Declining Outbreak Population of the Spruce Budworm, Choristoneura Fumiferana (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae)

insects Article Avian Predation in a Declining Outbreak Population of the Spruce Budworm, Choristoneura fumiferana (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) Jacques Régnière 1,* , Lisa Venier 2 and Dan Welsh 3,† 1 Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service, Laurentian Forestry Centre, 1055 rue du PEPS, Quebec City, QC G1V 4C7, Canada 2 Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service, Great Lakes Forestry Centre, 1219 Queen St. E., Sault Ste. Marie, ON P6A 2E5, Canada; [email protected] 3 Environment and Climate Change Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service, Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3, Canada * Correspondence: [email protected] † Deceased. Simple Summary: Cages preventing access to birds were used to measure the rate of predation by birds in a spruce budworm population during the decline of an outbreak. Three species of budworm-feeding warblers were involved in this predation on larvae and pupae. It was found that bird predation is a very important source of mortality in declining spruce budworm populations, and that bird foraging behavior changes as budworm prey become rare at the end of the outbreak. Abstract: The impact of avian predation on a declining population of the spruce budworm, Cho- ristoneura fumifereana (Clem.), was measured using single-tree exclosure cages in a mature stand of balsam fir, Abies balsamea (L.), and white spruce, Picea glauca (Moench.) Voss. Bird population Citation: Régnière, J.; Venier, L.; censuses and observations of foraging and nest-feeding activity were also made to determine the Welsh, D. Avian Predation in a response of budworm-linked warblers to decreasing food availability. Seasonal patterns of foraging. Declining Outbreak Population of the as well as foraging success in the declining prey population was compared to similar information Spruce Budworm, Choristoneura from birds observed in another stand where the spruce budworm population was rising. -

Bird) Species List

Aves (Bird) Species List Higher Classification1 Kingdom: Animalia, Phyllum: Chordata, Class: Reptilia, Diapsida, Archosauria, Aves Order (O:) and Family (F:) English Name2 Scientific Name3 O: Tinamiformes (Tinamous) F: Tinamidae (Tinamous) Great Tinamou Tinamus major Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei O: Galliformes (Turkeys, Pheasants & Quail) F: Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor (Chachalacas, Guans & Curassows) Gray-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps F: Odontophoridae (New World Quail) Black-breasted Wood-quail Odontophorus leucolaemus Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge Dendrortyx leucophrys Marbled Wood-Quail Odontophorus gujanensis Spotted Wood-Quail Odontophorus guttatus O: Suliformes (Cormorants) F: Fregatidae (Frigatebirds) Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens O: Pelecaniformes (Pelicans, Tropicbirds & Allies) F: Ardeidae (Herons, Egrets & Bitterns) Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis O: Charadriiformes (Sandpipers & Allies) F: Scolopacidae (Sandpipers) Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius O: Gruiformes (Cranes & Allies) F: Rallidae (Rails) Gray-Cowled Wood-Rail Aramides cajaneus O: Accipitriformes (Diurnal Birds of Prey) F: Cathartidae (Vultures & Condors) Black Vulture Coragyps atratus Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura F: Pandionidae (Osprey) Osprey Pandion haliaetus F: Accipitridae (Hawks, Eagles & Kites) Barred Hawk Morphnarchus princeps Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus Gray-headed Kite Leptodon cayanensis Northern Harrier Circus cyaneus Ornate Hawk-Eagle Spizaetus ornatus Red-tailed -

Birding Brochure

2OAD 0ROPERTYBOUNDARY 3ALATOEXHIBITPATH around HEADQUARTERS 2ESTROOM TRAILS 3ALATOEXHIBITTRAILS 0ICNICSHELTER (ABITREK4RAIL 4RAILMARKER 0EA2IDGE4RAIL 7ARBLER2IDGE4RAIL "ENCH KENTUCKY 0RAIRIE4RAIL 'ATE FISH and WILDLIFE 2ED HEADQUARTERS 2ED "LUE "LUE 2ED 3ALATO 2ED 7ILDLIFE %DUCATION AREA #ENTER HABITAT Moist soil areas Water levels in ponds and wetlands naturally rise and fall on a seasonal basis. When biologists attempt to mimic this natural TYPES system it is called moist soil management. Lowering water levels during the summer months encourages vegetation to grow. Shore- Riparian zones birds will frequent the draining areas in the late summer and fall. Riparian zones occur along creek and river margins and During the fall and winter, the flooded vegetation in larger moist often contain characteristic vegetation such as river birch, soil units can provide food and cover for migrating and wintering sycamore and silver maple. Because of their proximity to waterfowl. Biologists can target species groups by simply altering water, these areas serve as habitat for frogs, egg laying sites water levels. Common yellowthroat can be observed during migra- !RNOLD-ITCHELL"LDG for salamanders, and watering holes for other wildlife includ- tion and the breeding season. Sandpipers feed along the shoreline ing birds. To see one of our best examples, hike the Pea Ridge during migration. loop trail and look for areas that fit this description. The Aca- dian flycatcher is just one species that often uses these areas. Woodland This type of habitat is great for many 5PPER Grassland Lakes species of birds, as the tree canopy over- 3PORTSMANS Once common to the Bluegrass Lakes are formed when water gathers head provides excellent hiding places. -

Checklist of Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds and Mammals of New York

CHECKLIST OF AMPHIBIANS, REPTILES, BIRDS AND MAMMALS OF NEW YORK STATE Including Their Legal Status Eastern Milk Snake Moose Blue-spotted Salamander Common Loon New York State Artwork by Jean Gawalt Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Fish and Wildlife Page 1 of 30 February 2019 New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Fish and Wildlife Wildlife Diversity Group 625 Broadway Albany, New York 12233-4754 This web version is based upon an original hard copy version of Checklist of the Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds and Mammals of New York, Including Their Protective Status which was first published in 1985 and revised and reprinted in 1987. This version has had substantial revision in content and form. First printing - 1985 Second printing (rev.) - 1987 Third revision - 2001 Fourth revision - 2003 Fifth revision - 2005 Sixth revision - December 2005 Seventh revision - November 2006 Eighth revision - September 2007 Ninth revision - April 2010 Tenth revision – February 2019 Page 2 of 30 Introduction The following list of amphibians (34 species), reptiles (38), birds (474) and mammals (93) indicates those vertebrate species believed to be part of the fauna of New York and the present legal status of these species in New York State. Common and scientific nomenclature is as according to: Crother (2008) for amphibians and reptiles; the American Ornithologists' Union (1983 and 2009) for birds; and Wilson and Reeder (2005) for mammals. Expected occurrence in New York State is based on: Conant and Collins (1991) for amphibians and reptiles; Levine (1998) and the New York State Ornithological Association (2009) for birds; and New York State Museum records for terrestrial mammals. -

Timing of Migration and Status of Vireos (Vireonidae) in Louisiana J

J. Field Ornithol., 67(1):119-140 TIMING OF MIGRATION AND STATUS OF VIREOS (VIREONIDAE) IN LOUISIANA J. V. P•MSEN,JR., STEWN W. C•qDIVV,•X. ND DONN^ L. DITr• Museum of Natural Science Louisiana State University Baton Rouge,Louisiana 70803 USA Abstract.--Data are presentedon the statusof the vireos (Vireonidae) that occur in Louisi- ana. Basedprimarily on year-round surveysat coastalsites in southwesternLouisiana and censusesat an inland site in central Louisiana,data on timing of migration are presented for White-eyed (Vireo g'riseus),Solitary ( V. solitarius),Yellow-throated ( V. flavifrons), Phila- delphia (V. philadelphicus),and Red-eyed(V. olivaceus)vireos. In general,migrant vireosin spring are much more common on the coastthan inland, whereasthe reverseis true in fall. Bell's Vireo (V. belli•) has been recorded 12 times in southern Louisianabetween 4 November and 22January; this representsa substantialportion of all late fall/early winter recordsfrom eastern North America. No documented recordsexist of Yellow-throatedVireo from early November to early March for Louisiana,or probablyelsewhere in the Gulf Coast region, despitenumerous published sight records.Warbling Vireo (V. gilvus) has declined dramat- ically as a breeding speciesin Louisianafor unknown reasons;there have been almostno reportsof breeding birdsfor three decades.Two specimensof the subspeciesV. g. swainsonii from western North America have been collected in Louisiana, one of which is the first winter specimen of the speciesfor eastern North America. One specimen of White-eyed Vireo from Louisianais V. g'riseusmicrus;, this representsthe first record of this taxon north of southern Texas. One of the three Louisiana specimen records for Bell's Vireo is of a subspecies(V. -

Learn About Texas Birds Activity Book

Learn about . A Learning and Activity Book Color your own guide to the birds that wing their way across the plains, hills, forests, deserts and mountains of Texas. Text Mark W. Lockwood Conservation Biologist, Natural Resource Program Editorial Direction Georg Zappler Art Director Elena T. Ivy Educational Consultants Juliann Pool Beverly Morrell © 1997 Texas Parks and Wildlife 4200 Smith School Road Austin, Texas 78744 PWD BK P4000-038 10/97 All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems – without written permission of the publisher. Another "Learn about Texas" publication from TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE PRESS ISBN- 1-885696-17-5 Key to the Cover 4 8 1 2 5 9 3 6 7 14 16 10 13 20 19 15 11 12 17 18 19 21 24 23 20 22 26 28 31 25 29 27 30 ©TPWPress 1997 1 Great Kiskadee 16 Blue Jay 2 Carolina Wren 17 Pyrrhuloxia 3 Carolina Chickadee 18 Pyrrhuloxia 4 Altamira Oriole 19 Northern Cardinal 5 Black-capped Vireo 20 Ovenbird 6 Black-capped Vireo 21 Brown Thrasher 7Tufted Titmouse 22 Belted Kingfisher 8 Painted Bunting 23 Belted Kingfisher 9 Indigo Bunting 24 Scissor-tailed Flycatcher 10 Green Jay 25 Wood Thrush 11 Green Kingfisher 26 Ruddy Turnstone 12 Green Kingfisher 27 Long-billed Thrasher 13 Vermillion Flycatcher 28 Killdeer 14 Vermillion Flycatcher 29 Olive Sparrow 15 Blue Jay 30 Olive Sparrow 31 Great Horned Owl =female =male Texas Birds More kinds of birds have been found in Texas than any other state in the United States: just over 600 species. -

Bird Checklist of the Ten Thousand Islands National Wildlife Refuge

Shrikes & Vireos , cont. SP S F W Warblers SP S F W SP S F W Cardinals & Allies U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service _____ Philadelphia Vireo _____ Blue-winged Warbler R R R R _____ Summer Tanager R R R R _____ Red-eyed Vireo _____ Golden-winged Warbler R R F F F _____ Scarlet Tanager U U Bird Checklist of the Ten Thousand ______Black Whiskered Vireo _____ Tennessee Warbler R R U U R _____ Northern Cardinal C C C C _____ Orange-crowned Warbler U U U _____ Rose-breasted Grosbeak U U R Islands National Wildlife Refuge Jays & Crows _____ Nashville Warbler R R _____ Blue Grosbeak R R _____ Blue Jay F F F F _____ Northern Parula C C C C _____ Indigo Bunting U U U _____ Florida Scrub-Jay R R R R _____ Yellow Warbler R R U R _____ Painted Bunting U U U _____ American Crow C C C C _____ Chestnut-sided Warbler R U _____ Fish Crow C C C C _____ Magnolia Warbler U U R Blackbirds _____ Cape May Warbler R R _____ Bobolink R R Swallows _____ Black-throated Blue Warbler F F R _____ Red-winged Blackbird C C C C _____ Purple Martin F F U _____ Yellow-rumped Warbler F F C _____ Eastern Meadowlark R R R R _____ Tree Swallow C C C _____ Black-throated Green Warbler U U U _____ Yellow-headed Blackbird R R _____ Northern Rough- _____ Blackburnian Warbler R R R _____ Rusty Blackbird R R winged Swallow U U U U _____ Yellow-throated Warbler F R F F _____ Common Grackle C C C C _____ Bank Swallow R R _____ Pine Warbler C C C C _____ Boat-tailed Grackle C C C C _____ Cliff Swallow R R _____ Prairie Warbler F F F F _____ Bronzed Cowbird R R R _____ Cave Swallow R R R _____ -

Effects of Spruce Budworm (<I>Choristoneura Fumiferana</I> (Clem.)) Outbreaks on Boreal Mixed-Wood Bird Communities

Copyright © 2009 by the author(s). Published here under license by the Resilience Alliance. Venier, L. A., J. L. Pearce, D. R. Fillman, D. K. McNicol, and D. A. Welsh. 2009. Effects of spruce budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana (Clem.)) outbreaks on boreal mixed-wood bird communities. Avian Conservation and Ecology - Écologie et conservation des oiseaux 4(1): 3. [online] URL: http://www.ace- eco.org/vol4/iss1/art3/ Research Papers Effects of Spruce Budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana (Clem.)) Outbreaks on Boreal Mixed-Wood Bird Communities Effets des épidémies de Tordeuse des bourgeons de l’épinette (Choristoneura fumiferana (Clem.)) sur les communautés d’oiseaux de la forêt boréale mixte Lisa A. Venier 1, Jennie L. Pearce 2, Don R. Fillman 3, Don K. McNicol 3, and Dan A. Welsh 4 ABSTRACT. This study examined the influence of a spruce budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana (Clem.)) outbreak on a boreal mixed-wood bird community in forest stands ranging in age from 0 to 223 yr. We asked if (1) patterns of species response were consistent with the existence of spruce budworm specialists, i.e., species that respond in a stronger quantitative or qualitative way than other species; (2) the superabundance of food made it possible for species to expand their habitat use in age classes that were normally less used; and (3) the response to budworm was limited to specialists or was it more widespread. Results here indicated that three species, specifically the Bay-breasted Warbler (Dendroica castanea), Tennessee Warbler (Vermivora peregrina), and Cape May Warbler (Dendroica tigrina), had a larger numerical response to the budworm outbreak. -

Status of Cape May Warbler in Alberta 2001

Status of the Cape May Warbler (Dendroica tigrina) in Alberta Michael Norton Alberta Wildlife Status Report No. 33 March 2001 Published By: Publication No. T/596 ISBN: 0-7785-1467-6 ISSN: 1206-4912 Series Editor: Isabelle M. G. Michaud Senior Editor: David R. C. Prescott Illustrations: Brian Huffman For copies of this report, contact: Information Centre - Publications Alberta Environment Natural Resources Service Main Floor, Great West Life Building 9920 - 108 Street Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T5K 2M4 Telephone: (780) 422-2079 OR Information Service Alberta Environment #100, 3115 - 12 Street NE Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2E 7J2 Telephone: (780) 297-3362 Visit our web site at : http://www.gov.ab.ca/env/fw/status/reports/index.html This publication may be cited as: Norton, M.R. 2001. Status of the Cape May Warbler (Dendroica tigrina) in Alberta. Alberta Environment, Fisheries and Wildlife Management Division, and Alberta Conservation Association, Wildlife Status Report No. 33, Edmonton, AB. 20 pp. ii PREFACE Every five years, the Fisheries and Wildlife Management Division of Alberta Natural Resources Service reviews the status of wildlife species in Alberta. These overviews, which have been conducted in 1991 and 1996, assign individual species to ‘colour’ lists that reflect the perceived level of risk to populations that occur in the province. Such designations are determined from extensive consultations with professional and amateur biologists, and from a variety of readily available sources of population data. A primary objective of these reviews is to identify species that may be considered for more detailed status determinations. The Alberta Wildlife Status Report Series is an extension of the 1996 Status of Alberta Wildlife review process, and provides comprehensive current summaries of the biological status of selected wildlife species in Alberta.