Thesisx-Xfinal.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consumer Watch Information Dissemination; an Effi Cient, Transparent and Business Wpublication from the National 3

October 2013 NCA’s Vision To become the most forward-looking and innovative Communications Dear Valued Consumers, Regulatory Authority in the sub- elcome to this fi rst edition 2. Empower consumers through region; by creating and maintaining of the Consumer Watch information dissemination; an effi cient, transparent and business Wpublication from the National 3. Bridge existing gaps between friendly environment to enable Ghana Communications Authority (NCA) consumers and other stakeholders; become the premier destination of ICT This publication, which is solely 4. Give a voice to consumers that investment in the sub-region. dedicated to you, is aimed at educating, cannot reach their operators; Our Mission enlightening and protecting you with 5. Provide consumers with complete regard to communication services in the and accurate information in simple and To regulate the communications country. clear language. industry by setting and enforcing We want Consumer Watch to be the Hopefully, there will be other avenues high standards of competence and publication that you rely on to inform for us to get in touch with you for your performance to enable it to contribute you of on-going developments within benefi t. signifi cantly and fairly to the nation’s the industry and assure you that the We urge you to write to us with your prosperity through the provision of NCA takes consumer issues very suggestions and thoughts about how we effi cient and competitive services. seriously and is actively playing its role can together develop this industry for the of Consumer Protection in line with our benefi t of Ghana. National mandate. -

Social Media Index Report

Social Media Index Report February, 2016. Visit www.penplusbytes.org Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Over the past several years, social media has exhibited an exponential penetration into the daily lives of individuals, operations of businesses, and the interaction between governments and their respective people. It would not be far from the truth to assert that social media has become an important requirement for our daily personal and business life. It is against this backdrop that Penplusbytes, a leader in enhancing the work of journalists and promoting effective governance using technology in Africa, is introducing the maiden Social Media Index (SMI) report on Ghana's print, and electronic media - Radio and Television. The SMI report takes a look at the performance of established newspapers, radio and TV stations in Ghana regarding their activity and following on social media as at February 8th, 2016. Essentially, this report measures how these media entities utilize their online platforms to reach out and engage their target audience by employing a quantitative research module. The module provides relevant numerical figures which informs the rankings. TABLE OF CONTENT 1. Introduction ……………………………………………………………….1 2. Radio Index……………………………...………………………………...2 3. TV Index…………………………………………………………………..6 4. Newspaper Index…………………………………………………………..9 5. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………12 1. INTRODUCTION Ghana is undeniably experiencing an explosion of social media presence where Facebook for instance is 2nd most visited website—above local news sites according to the January 2016 Top websites ranking released by SimilarWeb.com. Ghana currently accounts for about 2,900,000 of all Facebook users as at January 2016. Consider this, if Facebook were a country, it would be the 3rd most populous country in the world. -

Kpelle Guba Isaac

University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh TECHNOLOGY AND NEWS PRODUCTION: THE CASE OF GHANA TELEVISION AND TV3 LIMITED BY KPELLE GUBA ISAAC 10550882 THIS THESIS IS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF GHANA, LEGON IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY DEGREE (MPHIL) IN THEATRE ARTS (MEDIA STUDIES OPTION) JULY, 2017 University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh DECLARATION I declare that except for references to other people’s work that have been duly acknowledged, this thesis is the result of my research conducted at the Department of Theatre Arts, University of Ghana, Legon. I take sole responsibility for any shortcomings that the work may have. …………………………………… Isaac Kpelle Guba (Student) Date……………………………. …………………………………… …………………………………… Dr. Samuel Benagr Dr. Joyce Osei Owusu (Supervisor) (Supervisor) Date……………………………. Date……………………………. i University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh ABSTRACT The invention of new media technologies is always a catalyst for change in the broadcast industry. This change facilitates and enhances the creation, processing, sharing and dissemination of information in the industry. With the introduction of new technologies such as the internet, satellite cable system and fibre optics in broadcasting, media practice across national boundaries has taken a turn for the better. The advancement in technology has radically changed and transformed the delivery of news footage to the newsroom in terms of immediacy and timeliness of news for broadcast. This study employs a comparative and phenomenological qualitative research methods with participatory observation and in-depth interview of respondents of two television stations in Ghana - GTV and TV3 to ascertain how they are responding to the advantages of this era of digital technology using diffusion of innovation theory. -

ASHESI UNIVERSITY COLLEGE by NICOLA OSEI GERNING

ASHESI UNIVERSITY COLLEGE THE STATE OF LOCAL CONTENT CHILDREN’S TELEVISON PROGRAMS: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE PAST AND PRESENT STATE OF CHILDREN’S TELEVISION IN GHANA By NICOLA OSEI GERNING Dissertation submitted to the Department of Management Information Systems Ashesi University College In partial fulfillment of Science degree in Management Information Systems APRIL 2013 i I hereby declare that this dissertation is the result of my own original work and that no part of it has been presented for another degree in this university or elsewhere. Candidate’s Signature: …………………………………………………………………… Candidate’s Name: ……………………………………………… Date: ………………………….. I hereby declare that the preparation and presentation of this thesis Report were supervised in accordance with the guidelines on supervision of thesis laid down by Ashesi University College. Supervisor’s Signature: …………………………………………………………………….. Supervisor’s Name: ……………………………………………. Date: ………………………………….. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Starting and ending the journey on this research has been challenging and tough one but in all this, I thank God so much for his grace, mercies and strength. To my parents and siblings who stood by me when the going got tough, I say a very big thank and hope you continue to be there for me in future research. I would like to thank Enyonam Osei- Hwere whose work proved to be very instrumental in this dissertation. Program Managers at GTV, Metro TV, TV3 and Visat 1 Mr. Assan, Mr. Osei Tutu and Josiah and Anthony, I am very grateful for your time and assistance. Mr. Nat Lomo-Mainoo, you inspired and encouraged me to continue with this research when others discouraged me and I am very grateful for that. -

Social Media Index Report (Radio, Television and Newspaper)

Social Media Index Report (Radio, Television and Newspaper) March, 2017. Visit www.penplusbytes.org Email: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENT 1. Introduction ………………………………………………………………1 2. Radio Index……………………………...………………………………..2 3. TV Index…………………………………………………………………..5 4. Newspaper Index………………………………………………………..8 5. Discussions……………………………………………………… ……. 11 6. Conclusion………………………………………………………. ….…12 1. INTRODUCTION The transition towards digital media and social networking has picked up tremendous pace globally with many forward thinking newsrooms and media entities embracing what has long been predicted as the new force in news generation and dissemination practices. Premised on a set objective to enhance the work of journalists using technology in Ghana, the 1st Quarter Social Media Index (SMI) report for 2017 gauges the extent to which Ghana’s traditional media are using this important space. The March 2017 report reviews the outlook and performance of various Newspapers, Radio and TV establishments in Ghana based on their presence, followers and likes on social media; particularly Facebook and Twitter. With collected data remaining valid as at the 31st March, 2017, this report measures how media entities utilize their online platforms to reach out and engage their target audience by employing a quantitative research module. The module provides relevant numerical figures which informed the rankings. Acknowledging the existence of other performance metrics nonetheless, this SMI report assesses the presence and performance of various media -

I VIDEO PRODUCTION in GHANA: a STUDY of POSTPRODUCTION by Ralitsa Diana Debrah (BFA Graphic Design) a Thesis Submitted to the S

VIDEO PRODUCTION IN GHANA: A STUDY OF POSTPRODUCTION By Ralitsa Diana Debrah (BFA Graphic Design) A Thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF COMMUNICATION DESIGN Faculty of Art College of Art and Social Sciences © March, 2010, Department of Communication Design i DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work towards the award of Master of Communication Design and that, to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published by another person nor material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree of the University, except where due acknowledgment has been made in the text. Ralitsa Diana Debrah PG1150007 ….……...…..….. ……………….. Student’s name ID Signature Date Certified by: Mr. Kwabena Kusi-Appouh ..………………………. ……………….. (Supervisor) Signature Date Certified by: Mr. J. W. A. Appiah ..……………………… ……………….. (Head of Department) Signature Date ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I sincerely appreciate the help received from the lecturers of - NAFTI to complete this project. I am glad to suggest interesting ideas that can be used to better video production in Ghana. Special thanks to Mr. Allassani and all his staff members for all their support, knowledge and feedback received throughout the thesis. Maame Esi Adjei Boateng’s willingness to provide guidance was invaluable. I express my profound gratitude to many who helped me in one way or the other but whose names have not been mentioned. I express my sincere appreciation, to Mr. J. W. A. Appiah for your encouragement throughout the years of my study and taking up the challenge together with your administration to support the development of this new course M. -

University of Education, Winneba Television Channel

University of Education, Winneba http://ir.uew.edu.gh UNIVERSITY OF EDUCATION, WINNEBA TELEVISION CHANNEL BRANDING IN GHANA: A STUDY OF TELEVISION IDENTS NYARKO, AYU JOEL EMMANUEL A THESIS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC EDUCATION, SCHOOL OF CREATIVE ARTS, SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF EDUCATION, WINNEBA IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY (ARTS AND CULTURE) DEGREE JULY, 2015 University of Education, Winneba http://ir.uew.edu.gh DECLARATION Student’s Declaration I Emmanuel Joel Ayu Nyarko declare that this thesis with the exception of quotations and references contained in published works which have all been identified and duly acknowledged, is entirely my own original work, and it has not been submitted, either in part or whole, for any degree elsewhere. .............................................. ….......................... Date Supervisor’s Declaration I hereby declare that the preparation and presentation of this work was supervised in accordance with the guidelines of supervision of thesis as laid down by the University of Education, Winneba. Name of Supervisor: Patrique deGraft-Yankson, PHD. ........................................... ......................... Date University of Education, Winneba http://ir.uew.edu.gh ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest appreciation to GTV, TV3 and UTV for assisting me through this thesis especially during the data collection stage. A special gratitude goes to all the creative departments of GTV, TV3 and UTV for their support. My heartfelt gratitude goes to Dr. Patrique deGraft-Yankson whose supervision, tuition and stimulating suggestions helped me see the big picture about research and guided me to a successful completion of this study. Furthermore, I would also like to acknowledge with much appreciation the crucial role of Dr Sarah Djsane of National Film and Television Institute and Dr. -

Ghana-Live-Tv

1 / 2 Ghana-live-tv Jan 16, 2020 — The Accra-based television station Citi TV will go online on DSTV today. A decision likely to significantly increase its audience to acquire a larger .... 3 days ago — CHICAGO — She's won a local pageant, created a cosmetic line and has supplied hundreds of shoes to children in Ghana. At just 12 years old, .... GhanaLive TV provides live stream of popular Ghana TV channel - Adom TV. Read more. Collapse. Reviews. Review policy and info. 3.6. 45 total. 5. 4. 3. 2. 1.. Feb 23, 2021 — Ignatius Annor, a journalist in Ghana, came out as gay during a live television broadcast on Monday (22 February), a stunning move in a .... Adom TV is your ultimate station. Tonton, Most Popular, Latest, Live, Premium, Shows, Movies, Channels, TV3, 8TV, ntv7, TV9 TV3 Ghana. com untuk tonton .... South Africa vs Ghana - March 25, 2021 - Live Streaming and TV Listings, Live Scores, News and Videos :: Live Soccer TV.. LiveGhanaTV provides the live streaming of GTV, GTV Sports, Adom TV, UTV Ghana, TV3 Ghana, Joy Prime,TV Africa and more. LiveGhanaTV also provides .... Live TV/Radio; Media . Top story. Election petition: Nothing stops Akufo-Addo from being sworn-in – Samson Lardy Anyenini . Advertisement. News. Ghana .... Watch online to Ghana TV stations including Adom TV, Joy News, GTV, TV 3, TV Africa and many more.. Ghana Live Tv , Ghana Tv Stations Live Streaming , Ghana online live tv, Ghana Live Soccer tv Streaming , Ghana Soccer Live Streaming. Live-Auktion von 1-2-3.tv » jetzt live mitbieten bei unseren Auktionen ✓ die Chance auf tolle Produkte zu Schnäppchenpreisen ✓ live auf 1-2-3.tv!. -

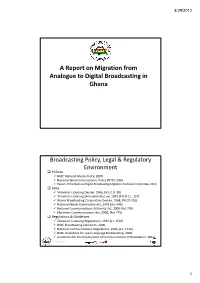

A Report on Migration from Analogue to Digital Broadcasting in Ghana

3/29/2012 A Report on Migration from Analogue to Digital Broadcasting in Ghana Broadcasting Policy, Legal & Regulatory Environment Policies V NMC National Media Policy, 2000 V National Telecommunications Policy (NTP), 2005 V Report of the National Digital Broadcasting Migration Technical Committee, 2010 Laws V Television Licensing Decree, 1966, (N.L.C.D. 89) V Television Licensing (Amendment) Law, 1991 (P.N.D.C.L. 257) V Ghana Broadcasting Corporation Decree, 1968, (NLCD 226) V National Media Commission Act, 1993 (Act 449) V National Communications Authority Act, 2008 (Act 769) V Electronic Communications Act, 2008, (Act 775) Regulations & Guidelines V Television Licensing Regulations, 1991 (L.I. 1520) V NMC Broadcasting Standards, 2000 V National Communications Regulations, 2003, (L.I. 1719) V NMC Guidelines for Local Language Broadcasting, 2009 V Guidelines for the Deployment of Communications Infrastructure, 2010 13 Oct 2011 2 1 3/29/2012 Composition of Communications Space By Number in operation Category 2004 200 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 5 Fixed 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 Line Cellular 4 4 4 4 4 5 5 5 ISPs 25 29 32 34 35 35 35 35 FM 84 84 127 129 144 171 190 220 Radio TV 8 8 10 11 13 14 14 16 13 Oct 2011 3 Composition of Accesslines up to June 2011 13 Oct 2011 4 2 3/29/2012 Mobile Telephony Penetration Rates 2000 – 2011 100.0 90.0 80.0 70.0 60.0 50.0 40.0 30.0 20.0 PercentagePenetration 10.0 0.0 Pen_Rate% 13 Oct 2011 5 Distribution of FM Stations in Ghana as of 2011 45 40 35 30 25 Institutional Community 20 Public/Government Private/Commercial -

Social Media Index Report

Social Media Index Report February, 2016. Visit www.penplusbytes.org Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Over the past several years, social media has exhibited an exponential penetration into the daily lives of individuals, operations of businesses, and the interaction between governments and their respective people. It would not be far from the truth to assert that social media has become an important requirement for our daily personal and business life. It is against this backdrop that Penplusbytes, a leader in enhancing the work of journalists and promoting effective governance using technology in Africa, is introducing the maiden Social Media Index (SMI) report on Ghana's print, and electronic media - Radio and Television. The SMI report takes a look at the performance of established newspapers, radio and TV stations in Ghana regarding their activity and following on social media as at February 8th, 2016. Essentially, this report measures how these media entities utilize their online platforms to reach out and engage their target audience by employing a quantitative research module. The module provides relevant numerical figures which informs the rankings. TABLE OF CONTENT 1. Introduction ……………………………………………………………….1 2. Radio Index……………………………...………………………………...2 3. TV Index…………………………………………………………………..6 4. Newspaper Index…………………………………………………………..9 5. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………12 1. INTRODUCTION Ghana is undeniably experiencing an explosion of social media presence where Facebook for instance is 2nd most visited website—above local news sites according to the January 2016 Top websites ranking released by SimilarWeb.com. Ghana currently accounts for about 2,900,000 of all Facebook users as at January 2016. Consider this, if Facebook were a country, it would be the 3rd most populous country in the world. -

Communicate for Health Annual Report: Year 2 Cooperative Agreement No: AID-641-A-15-00003

Communicate for Health Annual Report: Year 2 Cooperative Agreement No: AID-641-A-15-00003 Project dates: November 10, 2014 – November 30, 2019 Reporting Period: October 1, 2015 – September 30, 2016 Draft submission date: October 10, 2016 Communicate for Health Annual Report: Year 2 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................. 2 Acronyms and Abbreviations ................................................................................................................ 3 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................... 5 Overview of Communicate for Health in Ghana ................................................................................... 7 Social and Behavior Change Communication and Media (ER1) ............................................................. 9 Capacity Building (ER2) ....................................................................................................................... 28 Development of One Local SBCC Organization to be a Recipient of USAID Funding (ER3) .................. 38 Monitoring and Evaluation .................................................................................................................. 42 Partnerships and Coordination ........................................................................................................... 49 Overview of what to expect -

Ghana Migration from Analogue to Digital Broadcasting

NATIONAL MEDIA COMMISSION A Report on Migration from Analogue to Digital Broadcasting in Ghana Broadcasting Policy, Legal & Regulatory Environment Policies NMC National Media Policy, 2000 National Telecommunications Policy (NTP), 2005 Report of the National Digital Broadcasting Migration Technical Committee, 2010 Laws Television Licensing Decree, 1966, (N.L.C.D. 89) Television Licensing (Amendment) Law, 1991 (P.N.D.C.L. 257) Ghana Broadcasting Corporation Decree, 1968, (NLCD 226) National Media Commission Act, 1993 (Act 449) National Communications Authority Act, 2008 (Act 769) Electronic Communications Act, 2008, (Act 775) Regulations & Guidelines Television Licensing Regulations, 1991 (L.I. 1520) NMC Broadcasting Standards, 2000 National Communications Regulations, 2003, (L.I. 1719) NMC Guidelines for Local Language Broadcasting, 2009 Guidelines for the Deployment of Communications Infrastructure, 2010 13 Oct 2011 2 Composition of Communications Space By Number in operation Category 2004 200 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Mid 5 2011 Fixed 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 Line Cellular 4 4 4 4 4 5 5 5 ISPs 25 29 32 34 35 35 35 35 FM 84 84 127 129 144 171 190 203 Radio TV 8 8 10 11 13 14 14 16 13 Oct 2011 3 Composition of Access lines up to June 2011 2010 2008 2006 2004 2002 2000 0 5000000 10000000 15000000 20000000 Kasapa (Expresso) Millicom (Tigo) Scancom (MTN) GT/Vodafone Mobile Zain (Airtel) GT/Vodafone Fixed Zain Fixed 13 Oct 2011 4 Mobile Telephony Penetration Rates 2000 – mid 2011 90.0 80.0 70.0 60.0 50.0 40.0 30.0 20.0 PercentagePenetration