Common Jazz Piano Voicings JB Dyas, Phd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Common Jazz Chord Symbols Here I Use the More Explicit Abbreviation 'Maj7' for Major Seventh

Common jazz chord symbols Here I use the more explicit abbreviation 'maj7' for major seventh. Other common abbreviations include: C² C²7 CMA7 and CM7. Here I use the abbreviation 'm7' for minor seventh. Other common abbreviations include: C- C-7 Cmi7 and Cmin7. The variations given for Major 6th, Major 7th, Dominant 7th, basic altered dominant and minor 7th chords in the first five systems are essentially interchangeable, in other words, the 'color tones' shown added to these chords (9 and 13 on major and dominant seventh chords, 9, 13 and 11 on minor seventh chords) are commonly added even when not included in a chord symbol. For example, a chord notated Cmaj7 is often played with an added 6th and/or 9th, etc. Note that the 11th is not one of the basic color tones added to major and dominant 7th chords. Only #11 is added to these chords, which implies a different scale (lydian rather than major on maj7, lydian dominant rather than the 'seventh scale' on dominant 7th chords.) Although color tones above the seventh are sometimes added to the m7b5 chord, this chord is shown here without color tones, as it is often played without them, especially when a more basic approach is being taken to the minor ii-V-I. Note that the abbreviations Cmaj9, Cmaj13, C9, C13, Cm9 and Cm13 imply that the seventh is included. Major triad Major 6th chords C C6 C% w ww & w w w Major 7th chords (basic structure: root, 3rd, 5th and 7th of root's major scale) 4 CŒ„Š7 CŒ„Š9 CŒ„Š13 w w w w & w w w Dominant seventh chords (basic structure: root, 3rd, 5th and b7 of root's major scale) 7 C7 C9 C13 w bw bw bw & w w w basic altered dominant 7th chords 10 C7(b9) C7(#5) (aka C7+5 or C+7) C7[äÁ] bbw bw b bw & w # w # w Minor 7 flat 5, aka 'half diminished' fully diminished Minor seventh chords (root, b3, b5, b7). -

Second Bassoon: Specialist, Support, Teamwork Dick Hanemaayer Amsterdam, Holland (!E Following Article first Appeared in the Dutch Magazine “De Fagot”

THE DOUBLE REED 103 Second Bassoon: Specialist, Support, Teamwork Dick Hanemaayer Amsterdam, Holland (!e following article first appeared in the Dutch magazine “De Fagot”. It is reprinted here with permission in an English translation by James Aylward. Ed.) t used to be that orchestras, when they appointed a new second bassoon, would not take the best player, but a lesser one on instruction from the !rst bassoonist: the prima donna. "e !rst bassoonist would then blame the second for everything that went wrong. It was also not uncommon that the !rst bassoonist, when Ihe made a mistake, to shake an accusatory !nger at his colleague in clear view of the conductor. Nowadays it is clear that the second bassoon is not someone who is not good enough to play !rst, but a specialist in his own right. Jos de Lange and Ronald Karten, respectively second and !rst bassoonist from the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra explain.) BASS VOICE Jos de Lange: What makes the second bassoon more interesting over the other woodwinds is that the bassoon is the bass. In the orchestra there are usually four voices: soprano, alto, tenor and bass. All the high winds are either soprano or alto, almost never tenor. !e "rst bassoon is o#en the tenor or the alto, and the second is the bass. !e bassoons are the tenor and bass of the woodwinds. !e second bassoon is the only bass and performs an important and rewarding function. One of the tasks of the second bassoon is to control the pitch, in other words to decide how high a chord is to be played. -

Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Xian, Qiao-Shuang, "Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études"" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2432. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2432 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. REDISCOVERING FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN’S TROIS NOUVELLES ÉTUDES A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Qiao-Shuang Xian B.M., Columbus State University, 1996 M.M., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF EXAMPLES ………………………………………………………………………. iii LIST OF FIGURES …………………………………………………………………………… v ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………………………………… vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………….. 1 The Rise of Piano Methods …………………………………………………………….. 1 The Méthode des Méthodes de piano of 1840 -

Naming a Chord Once You Know the Common Names of the Intervals, the Naming of Chords Is a Little Less Daunting

Naming a Chord Once you know the common names of the intervals, the naming of chords is a little less daunting. Still, there are a few conventions and short-hand terms that many musicians use, that may be confusing at times. A few terms are used throughout the maze of chord names, and it is good to know what they refer to: Major / Minor – a “minor” note is one half step below the “major.” When naming intervals, all but the “perfect” intervals (1,4, 5, 8) are either major or minor. Generally if neither word is used, major is assumed, unless the situation is obvious. However, when used in naming extended chords, the word “minor” usually is reserved to indicate that the third of the triad is flatted. The word “major” is reserved to designate the major seventh interval as opposed to the minor or dominant seventh. It is assumed that the third is major, unless the word “minor” is said, right after the letter name of the chord. Similarly, in a seventh chord, the seventh interval is assumed to be a minor seventh (aka “dominant seventh), unless the word “major” comes right before the word “seventh.” Thus a common “C7” would mean a C major triad with a dominant seventh (CEGBb) While a “Cmaj7” (or CM7) would mean a C major triad with the major seventh interval added (CEGB), And a “Cmin7” (or Cm7) would mean a C minor triad with a dominant seventh interval added (CEbGBb) The dissonant “Cm(M7)” – “C minor major seventh” is fairly uncommon outside of modern jazz: it would mean a C minor triad with the major seventh interval added (CEbGB) Suspended – To suspend a note would mean to raise it up a half step. -

Jimmy Raney Thesis: Blurring the Barlines By: Zachary Streeter

Jimmy Raney Thesis: Blurring the Barlines By: Zachary Streeter A Thesis submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Jazz History and Research Graduate Program in Arts written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and Dr. Henry Martin And approved by Newark, New Jersey May 2016 ©2016 Zachary Streeter ALL RIGHT RESERVED ABSTRACT Jimmy Raney Thesis: Blurring the Barlines By: Zach Streeter Thesis Director: Dr. Lewis Porter Despite the institutionalization of jazz music, and the large output of academic activity surrounding the music’s history, one is hard pressed to discover any information on the late jazz guitarist Jimmy Raney or the legacy Jimmy Raney left on the instrument. Guitar, often times, in the history of jazz has been regulated to the role of the rhythm section, if the guitar is involved at all. While the scope of the guitar throughout the history of jazz is not the subject matter of this thesis, the aim is to present, or bring to light Jimmy Raney, a jazz guitarist who I believe, while not the first, may have been among the first to pioneer and challenge these conventions. I have researched Jimmy Raney’s background, and interviewed two people who knew Jimmy Raney: his son, Jon Raney, and record producer Don Schlitten. These two individuals provide a beneficial contrast as one knew Jimmy Raney quite personally, and the other knew Jimmy Raney from a business perspective, creating a greater frame of reference when attempting to piece together Jimmy Raney. -

On Modulation —

— On Modulation — Dean W. Billmeyer University of Minnesota American Guild of Organists National Convention June 25, 2008 Some Definitions • “…modulating [is] going smoothly from one key to another….”1 • “Modulation is the process by which a change of tonality is made in a smooth and convincing way.”2 • “In tonal music, a firmly established change of key, as opposed to a passing reference to another key, known as a ‘tonicization’. The scale or pitch collection and characteristic harmonic progressions of the new key must be present, and there will usually be at least one cadence to the new tonic.”3 Some Considerations • “Smoothness” is not necessarily a requirement for a successful modulation, as much tonal literature will illustrate. A “convincing way” is a better criterion to consider. • A clear establishment of the new key is important, and usually a duration to the modulation of some length is required for this. • Understanding a modulation depends on the aural perception of the listener; hence, some ambiguity is inherent in distinguishing among a mere tonicization, a “false” modulation, and a modulation. • A modulation to a “foreign” key may be easier to accomplish than one to a diatonically related key: the ear is forced to interpret a new key quickly when there is a large change in the number of accidentals (i.e., the set of pitch classes) in the keys used. 1 Max Miller, “A First Step in Keyboard Modulation”, The American Organist, October 1982. 2 Charles S. Brown, CAGO Study Guide, 1981. 3 Janna Saslaw: “Modulation”, Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy (Accessed 5 May 2008), http://www.grovemusic.com. -

Analysis of Selected Percussion Literature: Concerto

ANALYSIS OF SELECTED PERCUSSION LITERATURE: CONCERTO FOR VIBRAPHONE AND ORCHESTRA BY NEY ROSAURO, SURFACE TENSION BY DAVE HOLLINDEN, URBAN SKETCHES FOR PERCUSSION TRIO BY LON W. CHAFFIN, TAKE FIVE BY PAUL DESMOND, AND DT SUPREME BY AUSTIN BARNES by AUSTIN LEE BARNES B.M.E., Fort Hays State University, 2010 A REPORT submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MUSIC Department of Music College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2012 Approved by: Major Professor Dr. Kurt Gartner Copyright AUSTIN LEE BANRES 2012 Abstract This is a report for anyone playing or teaching anyone of the following pieces: Concerto for Vibraphone and Orchestra by Ney Rosauro, Surface Tension by Dave Hollinden, Urban Sketches for Percussion Trio by Lon W. Chaffin, Take Five by Paul Desmond, or DT Supreme by Austin Barnes. The repertoire is analyzed by the method given in Jan Larue’s book Guidelines for Style and Analysis. The report includes interpretive decisions, technical considerations, harmonic analysis, and form. Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ vi List of Tables ................................................................................................................................ vii Dedication .................................................................................................................................... viii CHAPTER 1 - Concerto for Vibraphone -

Many of Us Are Familiar with Popular Major Chord Progressions Like I–IV–V–I

Many of us are familiar with popular major chord progressions like I–IV–V–I. Now it’s time to delve into the exciting world of minor chords. Minor scales give flavor and emotion to a song, adding a level of musical depth that can make a mediocre song moving and distinct from others. Because so many of our favorite songs are in major keys, those that are in minor keys1 can stand out, and some musical styles like rock or jazz thrive on complex minor scales and harmonic wizardry. Minor chord progressions generally contain richer harmonic possibilities than the typical major progressions. Minor key songs frequently modulate to major and back to minor. Sometimes the same chord can appear as major and minor in the very same song! But this heady harmonic mix is nothing to be afraid of. By the end of this article, you’ll not only understand how minor chords are made, but you’ll know some common minor chord progressions, how to write them, and how to use them in your own music. With enough listening practice, you’ll be able to recognize minor chord progressions in songs almost instantly! Table of Contents: 1. A Tale of Two Tonalities 2. Major or Minor? 3. Chords in Minor Scales 4. The Top 3 Chords in Minor Progressions 5. Exercises in Minor 6. Writing Your Own Minor Chord Progressions 7. Your Minor Journey 1 https://www.musical-u.com/learn/the-ultimate-guide-to-minor-keys A Tale of Two Tonalities Western music is dominated by two tonalities: major and minor. -

To View a Few Sample Pages of 30 Days to Better Jazz Guitar Comping

You will also find that you sometimes need to make big jumps across the neck to keep bass lines going. Keeping a solid bass line is more important than smooth voice leading. For example it’s more important to keep a bass line constantly going using simple chords rather than trying to find the hippest chords you know Day 24: Comping with Bass Lines After learning how to use a bass line with chords in the bossa nova, today’s lesson is about how to comp with bass lines in a more traditional jazz setting. Background on Comping with Bass Lines An essential comping technique that every guitarist learns at some point is to comp with bass lines. The two most important ingredients to this comping style are the feel and the bass line. As Joe Pass says “A good bass line must be able to stand by itself”, meaning that you add the chords where you can. Like many other subjects in this book, bass lines could fill up an entire book of their own, but this section will teach you the fundamental principles such as how to construct a bass line and apply it over the ii-V-I progression. What Chords Should I Use? As with bossa nova comping, it’s best to use simple voicings that are easy to grab to keep the bass line flowing as smoothly as possible. The chord diagram below shows the chords that are going to be used, notice that these are all simple inversions with no extensions, but they give the ear enough information to recognize the chord type and have roots on the bottom two strings. -

Playing Harmonica with Guitar & Ukulele

Playing Harmonica with Guitar & Ukulele IT’S EASY WITH THE LEE OSKAR HARMONICA SYSTEM... SpiceSpice upup youryour songssongs withwith thethe soulfulsoulful soundsound ofof thethe harmonicaharmonica alongalong withwith youryour GuitarGuitar oror UkuleleUkulele playing!playing! Information all in one place! Online Video Guides Scan or visit: leeoskarquickguide.com ©2013-2016 Lee Oskar Productions Inc. - All Rights Reserved Major Diatonic Key labeled in 1st Position (Straight Harp) Available in 14 keys: Low F, G, Ab, A, Bb, B, C, Db, D, Eb, E, F, F#, High G Key of C MAJOR DIATONIC BLOW DRAW The Major Diatonic harmonica uses a standard Blues tuning and can be played in the 1st Position (Folk & Country) or the 2 nd Position (Blues, Rock/Pop Country). 1 st Position: Folk & Country Most Folk and Country music is played on the harmonica in the key of the blow (exhale) chord. This is called 1 st Position, or straight harp, playing. Begin by strumming your guitar / ukulele: C F G7 C F G7 With your C Major Diatonic harmonica Key of C MIDRANGE in its holder, starting from blow (exhale), BLOW try to pick out a melody in the midrange of the harmonica. DRAW Do Re Mi Fa So La Ti Do C Major scale played in 1st Position C D E F G A B C on a C Major Diatonic harmonica. 4 4 5 5 6 6 7 7 ©2013-2016 Lee Oskar Productions Inc. All Rights Reserved 2nd Position: Blues, Rock/Pop, Country Most Blues, Rock, and modern Country music is played on the harmonica in the key of the draw (inhale) chord. -

JAZZ FUNDAMENTALS Jazz Piano, Theory, and More

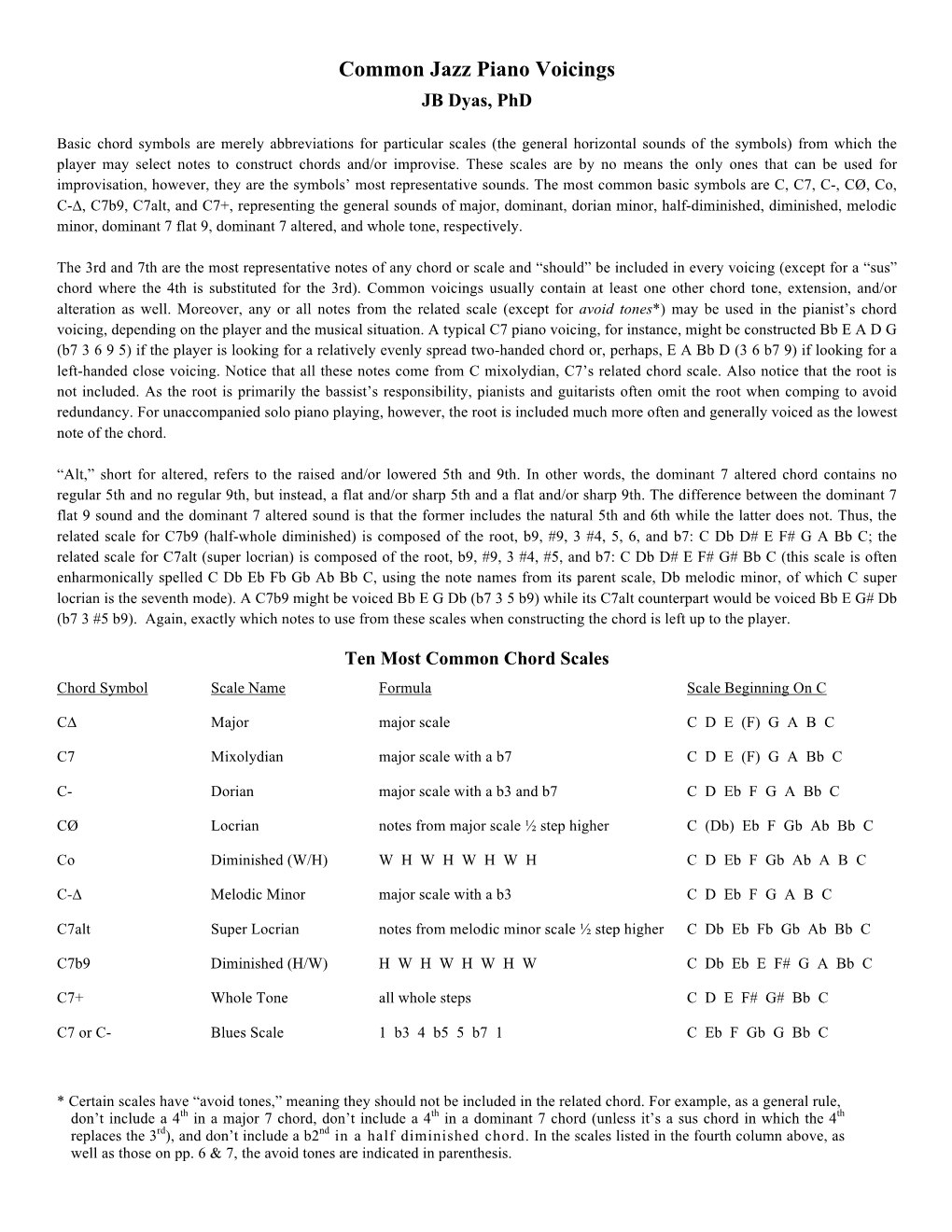

JAZZ FUNDAMENTALS Jazz Piano, Theory, and More Dr. JB Dyas 310-206-9501 • [email protected] 2 JB Dyas, PhD Dr. JB Dyas has been a leader in jazz education for the past two decades. Formerly the Executive Director of the Brubeck Institute, Dyas currently serves as Vice President for Education and Curriculum Development for the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz at UCLA in Los Angeles. He oversees the Institute’s education and outreach programs including Jazz In America: The National Jazz Curriculum (www.jazzinamerica.org), one of the most significant and wide-reaching jazz education programs in the world. Throughout his career, he has performed across the country, taught students at every level, directed large and small ensembles, developed and implemented new jazz curricula, and written for national music publications. He has served on the Smithsonian Institution’s Task Force for Jazz Education in America and has presented numerous jazz workshops, teacher-training seminars, and jazz "informances" around the globe with such renowned artists as Dave Brubeck and Herbie Hancock. A professional bassist, Dyas has appeared with Jamey Aebersold, David Baker, Jerry Bergonzi, Red Rodney, Ira Sullivan, and Bobby Watson, among others. He received his Master’s degree in Jazz Pedagogy from the University of Miami and PhD in Music Education from Indiana University, and is a recipient of the prestigious DownBeat Achievement Award for Jazz Education. 3 Jazz Fundamentals Text: Aebersold Play-Along Volume 54 (Maiden Voyage) Also Recommended: Jazz Piano Voicings for the Non-Pianist and Pocket Changes I. Chromatic Scale (all half steps) C C# D D# E F F# G G# A A# B C C Db D Eb E F Gb G Ab A Bb B C Whole Tone Scale (all whole steps) C D E F# G# A# C Db Eb F G A B Db ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________ II. -

Why Jazz Still Matters Jazz Still Matters Why Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Journal of the American Academy

Dædalus Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Spring 2019 Why Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, guest editors with Farah Jasmine Griffin Gabriel Solis · Christopher J. Wells Kelsey A. K. Klotz · Judith Tick Krin Gabbard · Carol A. Muller Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences “Why Jazz Still Matters” Volume 148, Number 2; Spring 2019 Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, Guest Editors Phyllis S. Bendell, Managing Editor and Director of Publications Peter Walton, Associate Editor Heather M. Struntz, Assistant Editor Committee on Studies and Publications John Mark Hansen, Chair; Rosina Bierbaum, Johanna Drucker, Gerald Early, Carol Gluck, Linda Greenhouse, John Hildebrand, Philip Khoury, Arthur Kleinman, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, Alan I. Leshner, Rose McDermott, Michael S. McPherson, Frances McCall Rosenbluth, Scott D. Sagan, Nancy C. Andrews (ex officio), David W. Oxtoby (ex officio), Diane P. Wood (ex officio) Inside front cover: Pianist Geri Allen. Photograph by Arne Reimer, provided by Ora Harris. © by Ross Clayton Productions. Contents 5 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson 13 Following Geri’s Lead Farah Jasmine Griffin 23 Soul, Afrofuturism & the Timeliness of Contemporary Jazz Fusions Gabriel Solis 36 “You Can’t Dance to It”: Jazz Music and Its Choreographies of Listening Christopher J. Wells 52 Dave Brubeck’s Southern Strategy Kelsey A. K. Klotz 67 Keith Jarrett, Miscegenation & the Rise of the European Sensibility in Jazz in the 1970s Gerald Early 83 Ella Fitzgerald & “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” Berlin 1968: Paying Homage to & Signifying on Soul Music Judith Tick 92 La La Land Is a Hit, but Is It Good for Jazz? Krin Gabbard 104 Yusef Lateef’s Autophysiopsychic Quest Ingrid Monson 115 Why Jazz? South Africa 2019 Carol A.