Arrow Video Arrow Video Arrow Video Arrow Video

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cial Climber. Hunter, As the Professor Responsible for Wagner's Eventual Downfall, Was Believably Bland but Wasted. How Much

cial climber. Hunter, as the professor what proves to be a sordid suburbia, responsible for Wagner's eventual are Mitchell/Woodward, Hingle/Rush, downfall, was believably bland but and Randall/North. Hunter's wife is wasted. How much better this film attacked by Mitchell; Hunter himself might have been had Hunter and Wag- is cruelly beaten when he tries to ner exchanged roles! avenge her; villain Mitchell goes to 20. GUN FOR A COWARD. (Universal- his death under an auto; his wife Jo- International, 1957.) Directed by Ab- anne Woodward goes off in a taxi; and ner Biberman. Cast: Fred MacMurray, the remaining couples demonstrate Jeffrey Hunter, Janice Rule, Chill their new maturity by going to church. Wills, Dean Stockwell, Josephine Hut- A distasteful mess. chinson, Betty Lynn. In this Western, Hunter appeared When Hunter reported to Universal- as the overprotected second of three International for Appointment with a sons. "Coward" Hunter eventually Shadow (released in 1958), he worked proved to be anything but in a rousing but one day, as an alcoholic ex- climax. Not a great film, but a good reporter on the trail of a supposedly one. slain gangster. Having become ill 21. THE TRUE STORY OF JESSE with hepatitis, he was replaced by JAMES. (20th Century-Fox, 1957.) Di- George Nader. Subsequently, Hunter rected by Nicholas Ray. Cast: Robert told reporters that only the faithful Wagner, Jeffrey Hunter, Hope Lange, Agnes Moorehead, Alan Hale, Alan nursing by his wife, Dusty Bartlett, Baxter, John Carradine. whom he had married in July, 1957, This was not even good. -

Y Birthday Festivities IC 17 Lewsr Ivy Wry " 'Acclaimed As 'Best Ever'

MAR NE CoR HISTic,oR PS II, y Birthday Festivities IC 17 lewsr ivy wry " 'Acclaimed as 'Best Ever' "Tremendous" . "best ings of all others who com- mand Marines, I say to you VOL. 12 No. 46 Marine Corps Air Station, Kanecille Bay, Hawaii November 15, 1963 I've ever been to" . "ter- - that no military commander rific chow" . "outstanding in the world could be more entertainment" . "beautiful fortunate or more successful cakes" . "wonderful pag- in battle than he who leads Marines Pay eant" . "we had a ball." United States Marines like These were but a few of the you men who are sitting exclamations from K-Bayites here tonight." State Taxes, who attended parties and balls After the ceremonies, some celebrating the Corps' 188th 365 couples adjourned to the Birthday last Saturday eve- E-Club for more entertainment JAG Advises ning. and dancing. K-Bay Marines and Navy- The Friday parade, Satur- The Staff Club was filled men who have not been filing I day balls and Sunday :wry- wall-to-wall with some 650 cel- state income tax returns with ices ranging over three days ebrants. Gen. Youngdale and their home states better take marked one of the most suc- Col. Paul T. Johnston, Station heed. cessful observances of the The Legal Assistance Policy Birthday ever conducted at K-Bay, according to See pages 4 and 5 for com- Division in the office of the those who it, plete photo coverage on K- Judge Advocate General ad- planned participated in Bay's birthday events in- vises that in the near future it - and enjoyed every minute of it. -

An Interview with Sergio Martino: an American in Rome

1 An interview with Sergio Martino: An American in Rome Giulio Olesen, Bournemouth University Introduction Sergio Martino (born Rome, 1938) is a film director known for his contribution to 1970s and 1980s Italian filone cinema. His first success came with the giallo Lo strano vizio della Signora Wardh (Next!) (1971), from which he moved to spaghetti westerns (Mannaja [A Man Called Blade], 1977), gialli (I corpi presentano tracce di violenza carnale [Torso], 1973), poliziotteschi (Milano trema: la polizia vuole giustizia [The Violent Professionals], 1973), horror movies (La montagna del dio cannibale [The Mountain of the Cannibal God], 1978; L’isola degli uomini pesce [Island of Mutations], 1979), science fiction movies (2019, dopo la caduta di New York [2019, After the Fall of New York], 1983) and comedies (Giovannona Coscialunga disonorata con onore [Giovannona Long-Thigh], 1973). His works witness the hybridization of international and local cinematic genres as a pivotal characteristic of Italian filone cinema. This face-to-face interview took place in Rome on 26 October 2015 in the venues premises of Martino’s production company, Dania Film, and addresses his horror and giallo productions. Much scholarship analyses filone cinema under the lens of cult or transnational cinema studies. In this respect, the interview aims at collecting Martino’s considerations regarding the actual state of debate on Italian filone cinema. Nevertheless, e Emphasis is put on a different approach towards this kind of cinema; an approach that aims at analysing filone cinema for its capacity to represent contemporaneous issues and concerns. Accordingly, introducing Martino’s relationship with Hollywood, the interview focuses on the way in which his horror movies managed to intercept register fears and neuroses of Italian society. -

“No Reason to Be Seen”: Cinema, Exploitation, and the Political

“No Reason to Be Seen”: Cinema, Exploitation, and the Political by Gordon Sullivan B.A., University of Central Florida, 2004 M.A., North Carolina State University, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2017 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Gordon Sullivan It was defended on October 20, 2017 and approved by Marcia Landy, Distinguished Professor, Department of English Jennifer Waldron, Associate Professor, Department of English Daniel Morgan, Associate Professor, Department of Cinema and Media Studies, University of Chicago Dissertation Advisor: Adam Lowenstein, Professor, Department of English ii Copyright © by Gordon Sullivan 2017 iii “NO REASON TO BE SEEN”: CINEMA, EXPLOITATION, AND THE POLITICAL Gordon Sullivan, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2017 This dissertation argues that we can best understand exploitation films as a mode of political cinema. Following the work of Peter Brooks on melodrama, the exploitation film is a mode concerned with spectacular violence and its relationship to the political, as defined by French philosopher Jacques Rancière. For Rancière, the political is an “intervention into the visible and sayable,” where members of a community who are otherwise uncounted come to be seen as part of the community through a “redistribution of the sensible.” This aesthetic rupture allows the demands of the formerly-invisible to be seen and considered. We can see this operation at work in the exploitation film, and by investigating a series of exploitation auteurs, we can augment our understanding of what Rancière means by the political. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Aa-428-Cinema-Sergio Leone

CINÉMA LE MYTHE, LE PAYSAGE ET L’ARCHITECTURE REVUS ET CORRIGÉS PAR SERGIO LEONE CHRISTOPHE LE GAC LEGEND, LANDSCAPE AND ARCHITECTURE REVISITED BY SERGIO LEONE REGARDS Parce que l’architecture se nourrit de tous les arts et de bien des sciences, cinéma, photographie, scénographie et sociologie trouvent aussi une place dans les pages d’AA. Dans ce numéro 428, place à l’architecture dans les westerns de Sergio Leone, à la Charles Bronson dans Il était une fois dans l’Ouest / Fondation Stavros Niarchos à Athènes, aux habitations de Once Upon a Time in the West, 1968. Notre-Dame-des-Landes, aux échanges entre Stéphane Maupin, architecte et Raphaël Vital-Durand, réalisateur et aux mises en Exposé à la Cinémathèque de scène aériennes de Yoann Bourgeois, acrobate et chorégraphe. Paris jusqu’au 27 janvier 2019, The work of Sergio Leone, the Sergio Leone fut le grand architecte western’s great deconstructivist Because architecture feeds on all the arts and many sciences, déconstructiviste du western. Dans architect, is on show at the cinema, photography, scenography and sociology have their place un double mouvement, il réussit à Paris Cinémathèque Film in the magazine. In this 428th issue, AA features architecture in renouveler un genre à bout de souffle Centre until 27 January 2019. Sergio Leone’s westerns, the Stavros Niarchos Foundation in Athens, tout en procédant à de véritables He succeeded in reinvigorating Notre-Dame-des-Landes dwellings, architect Stéphane Maupin in expérimentations plastiques. a genre that had run out of conversation with director Raphaël Vital-Durand and acrobat and steam, while experimenting choreographer Yoann Bourgeois’ aerial staging. -

Uw Cinematheque Announces Fall 2012 Screening Calendar

CINEMATHEQUE PRESS RELEASE -- FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE AUGUST 16, 2012 UW CINEMATHEQUE ANNOUNCES FALL 2012 SCREENING CALENDAR PACKED LINEUP INCLUDES ANTI-WESTERNS, ITALIAN CLASSICS, PRESTON STURGES SCREENPLAYS, FILMS DIRECTED BY ALEXSEI GUERMAN, KENJI MISUMI, & CHARLES CHAPLIN AND MORE Hot on the heels of our enormously popular summer offerings, the UW Cinematheque is back with the most jam-packed season of screenings ever offered for the fall. Director and cinephile Peter Bogdanovich (who almost made an early version of Lonesome Dove during the era of the revisionist Western) writes that “There are no ‘old’ movies—only movies you have already seen and ones you haven't.” With all that in mind, our Fall 2012 selections presented at 4070 Vilas Hall, the Chazen Museum of Art, and the Marquee Theater at Union South offer a moveable feast of outstanding international movies from the silent era to the present, some you may have seen and some you probably haven’t. Retrospective series include five classic “Anti-Westerns” from the late 1960s and early 70s; the complete features of Russian master Aleksei Guerman; action epics and contemplative dramas from Japanese filmmaker Kenji Misumi; a breathtaking survey of Italian Masterworks from the neorealist era to the early 1970s; Depression Era comedies and dramas with scripts by the renowned Preston Sturges; and three silent comedy classics directed by and starring Charles Chaplin. Other Special Presentations include a screening of Yasujiro Ozu’s Dragnet Girl with live piano accompaniment and an in-person visit from veteran film and television director Tim Hunter, who will present one of his favorite films, Tsui Hark’s Shanghai Blues and a screening of his own acclaimed youth film, River’s Edge. -

9. List of Film Genres and Sub-Genres PDF HANDOUT

9. List of film genres and sub-genres PDF HANDOUT The following list of film genres and sub-genres has been adapted from “Film Sub-Genres Types (and Hybrids)” written by Tim Dirks29. Genre Film sub-genres types and hybrids Action or adventure • Action or Adventure Comedy • Literature/Folklore Adventure • Action/Adventure Drama Heroes • Alien Invasion • Martial Arts Action (Kung-Fu) • Animal • Man- or Woman-In-Peril • Biker • Man vs. Nature • Blaxploitation • Mountain • Blockbusters • Period Action Films • Buddy • Political Conspiracies, Thrillers • Buddy Cops (or Odd Couple) • Poliziotteschi (Italian) • Caper • Prison • Chase Films or Thrillers • Psychological Thriller • Comic-Book Action • Quest • Confined Space Action • Rape and Revenge Films • Conspiracy Thriller (Paranoid • Road Thriller) • Romantic Adventures • Cop Action • Sci-Fi Action/Adventure • Costume Adventures • Samurai • Crime Films • Sea Adventures • Desert Epics • Searches/Expeditions for Lost • Disaster or Doomsday Continents • Epic Adventure Films • Serialized films • Erotic Thrillers • Space Adventures • Escape • Sports—Action • Espionage • Spy • Exploitation (ie Nunsploitation, • Straight Action/Conflict Naziploitation • Super-Heroes • Family-oriented Adventure • Surfing or Surf Films • Fantasy Adventure • Survival • Futuristic • Swashbuckler • Girls With Guns • Sword and Sorcery (or “Sword and • Guy Films Sandal”) • Heist—Caper Films • (Action) Suspense Thrillers • Heroic Bloodshed Films • Techno-Thrillers • Historical Spectacles • Treasure Hunts • Hong Kong • Undercover -

Catalogue of Photographs of Performers at the Embassy Theatre

Catalogue of Photographs of Performers and Shows in the Archives of the Embassy Theatre Foundation The archives of the Embassy Theatre Foundation hold more than 3000 artifacts, including more than 600 photographs of vaudevillians inscribed to Bud Berger (long-time stage man- ager at the Embassy Theatre, known as the Emboyd until 1952); more than 300 posters, playbills, programs, stools, and even guitars signed by the stars and casts of shows that have played at the Embassy Theatre over the past forty years, rang- ing from classic and current Broadway shows to acrobatic groups, choral ensembles, dance shows, ballet, stand-up comedians, rock bands, country singers, travel films, silent films, theatre organists, and so on; and hundreds of publicity photographs of performers, shows, and events at the theatre, primarily from the period following the establishment of the Embassy Theatre Foundation and its rescue of the theatre from the wrecking ball in 1975; and a nearly complete run of the journal of the American Theatre Organ Society. The archive is now almost fully catalogued and preserved in archival housing. Earlier excerpts from the catalogue (available on the Archives page of the Embassy Theatre’s web site) cover the photographs inscribed to Bud Berger and the posters, playbills, programs, stools, and so on from later shows at the Embassy. This is the third excerpt, covering the public- ity photographs of the last forty-five years and a few photographs of earlier events, Bud Berger, and other members of the stage crew. The publicity photographs are primarily of individ- ual performers, but a few shows are presented as well, including Ain’t Misbehavin’, Annie, Barnum, Bubbling Brown Sugar, Cabaret, California Suite, Cats, A Christ- mas Carol, Dancin’, Evita, Gypsy, I'm Getting My Act Together And Taking It On The Road, Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat, Peter Pan, Same Time Next Year, Side by Side by Sondheim, and Ziegfeld: A Night at the Follies. -

Quentin Tarantino Retro

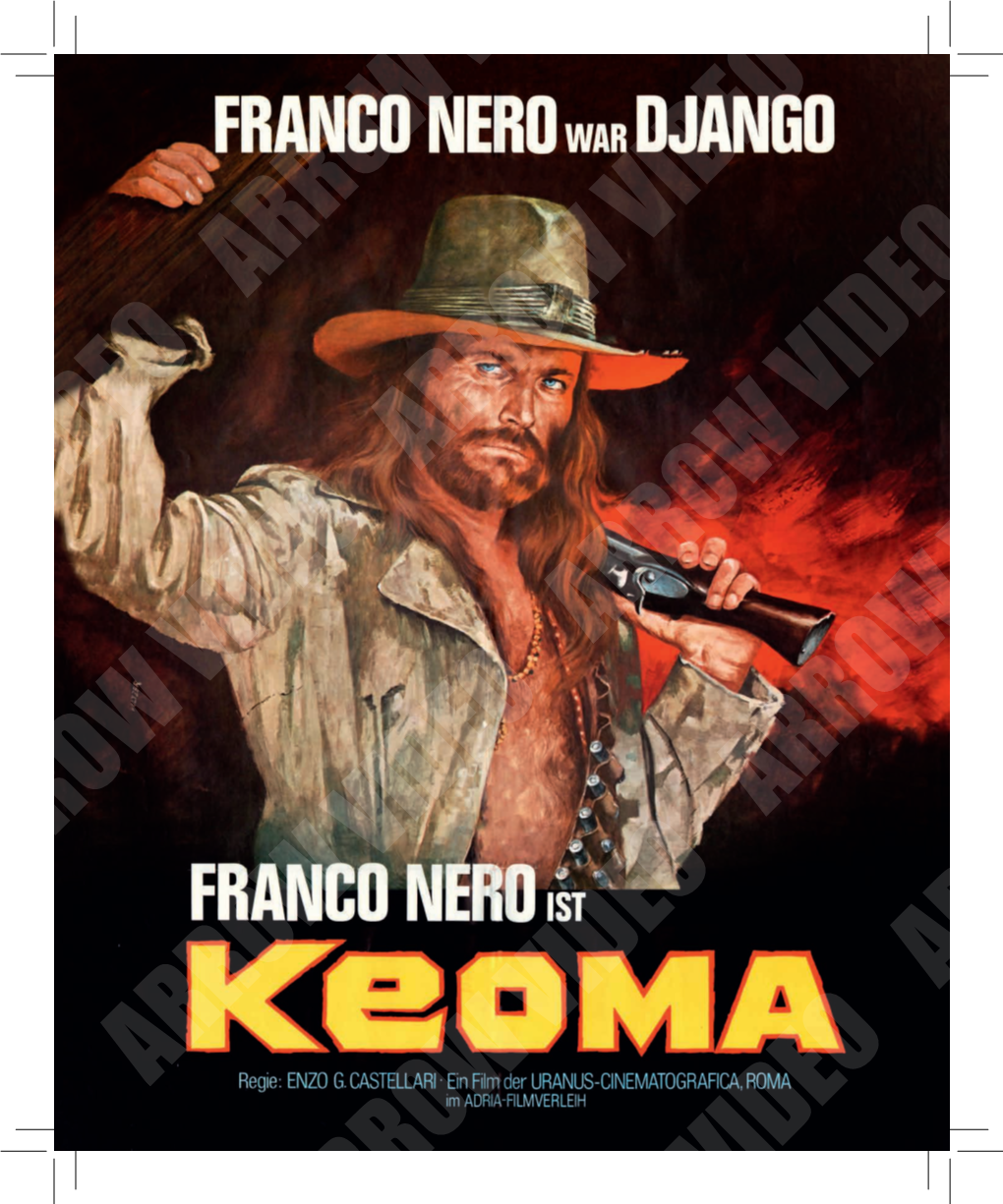

ISSUE 59 AFI SILVER THEATRE AND CULTURAL CENTER FEBRUARY 1– APRIL 18, 2013 ISSUE 60 Reel Estate: The American Home on Film Loretta Young Centennial Environmental Film Festival in the Nation's Capital New African Films Festival Korean Film Festival DC Mr. & Mrs. Hitchcock Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Howard Hawks, Part 1 QUENTIN TARANTINO RETRO The Roots of Django AFI.com/Silver Contents Howard Hawks, Part 1 Howard Hawks, Part 1 ..............................2 February 1—April 18 Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances ...5 Howard Hawks was one of Hollywood’s most consistently entertaining directors, and one of Quentin Tarantino Retro .............................6 the most versatile, directing exemplary comedies, melodramas, war pictures, gangster films, The Roots of Django ...................................7 films noir, Westerns, sci-fi thrillers and musicals, with several being landmark films in their genre. Reel Estate: The American Home on Film .....8 Korean Film Festival DC ............................9 Hawks never won an Oscar—in fact, he was nominated only once, as Best Director for 1941’s SERGEANT YORK (both he and Orson Welles lost to John Ford that year)—but his Mr. and Mrs. Hitchcock ..........................10 critical stature grew over the 1960s and '70s, even as his career was winding down, and in 1975 the Academy awarded him an honorary Oscar, declaring Hawks “a giant of the Environmental Film Festival ....................11 American cinema whose pictures, taken as a whole, represent one of the most consistent, Loretta Young Centennial .......................12 vivid and varied bodies of work in world cinema.” Howard Hawks, Part 2 continues in April. Special Engagements ....................13, 14 Courtesy of Everett Collection Calendar ...............................................15 “I consider Howard Hawks to be the greatest American director. -

Mario Bava: - Alberto Pezzotta, Mario Bava, Il Castoro

I GENERI POPOLARI DEL CINEMA ITALIANO: HORROR, WESTERN E COMMEDIA Orario delle lezioni Martedì ore 13-15 T30 Giovedì ore 10-12 T30 Ricevimento IV °PIANO Stanza 26 (tel. 06 /7259-5018) Martedì e Giovedì ore 12-13 Programma del CORSO (1) 1) Parte generale - “Slide del Corso” 2) Approfondimento a scelta di 2 trai seguenti autori o libri: - Mariapia Comand, Commedia all'italiana, Il Castoro - Alberto Pezzotta, Il western italiano, Il Castoro - Giovanni Spagnoletti / Antonio V.Spera , Risate all'italiana. Il cinema di commedia dal secondo dopoguerra ad oggi, UniversItalia - Venturini Simone, Horror italiano, Donzelli Su Dario Argento (scegliere un volume): a) Luca Lardieri, Dario Argento, Sovera b) Roberto Pugliese, Dario Argento, Il Castoro c) Vito Zagarrio, Argento vivo. Il cinema di Dario Argento tra genere e autorialità, Marsilio Su Mario Bava: - Alberto Pezzotta, Mario Bava, Il Castoro Programma del CORSO (2) Su Sergio Leone (scegliere un volume trai seguenti): a) Italo Moscati, Sergio Leone. Quando il cinema era grande, Lindau b) Christian Uva, Sergio Leone. Il cinema come favola, Ente dello Spettacolo (collana Le torri) Su Mario Monicelli: a) Leonardo de Franceschi (a cura di), Lo sguardo eclettico. Il cinema di Mario Monicelli, Marsilio b) Ivana Delvino, I film di Mario Monicelli, Gremese Editore Su Dino Risi: a) Valerio Caprara (a cura), Mordi e fuggi, Marsilio b) Irene Mazzetti, I film di Dino Risi, Gremese 3) Conoscenza di 15 film riguardanti l’argomento del corso (vedi slide successiva) Sugli autori o gli argomenti portati, possono (non devono) essere fatte delle tesine di circa 10.000 caratteri (spazi esclusi) che vanno consegnate SU CARTA (e non via email) IMPROROGABILMENTE ALMENO UNA SETTIMANA PRIMA DELL’ ESAME Previo accordo con il docente, si possono portare dei testi alternativi rispetto a quelli indicati. -

Bodies of Desire and Bodies in Distress

Bodies of Desire and Bodies in Distress Bodies of Desire and Bodies in Distress: The Golden Age of Italian Cult Cinema 1970-1985 By Xavier Mendik Bodies of Desire and Bodies in Distress: The Golden Age of Italian Cult Cinema 1970-1985, By Xavier Mendik This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Xavier Mendik All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5954-0, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5954-7 This book is dedicated with much love to Caroline and Zena CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................... ix Foreword ................................................................................................... xii Enzo G. Castellari Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 Bodies of Desire and Bodies of Distress beyond the ‘Argento Effect’ Chapter One .............................................................................................. 21 “There is Something Wrong with that Scene”: The Return of the Repressed in 1970s Giallo Cinema Chapter Two ............................................................................................