Adding Sound to Your N Scale NKP Fleet Maumee Basin Lines NKP Camp Car

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Super Chief – El Capitan See Page 4 for Details

AUGUST- lyerlyer SEPTEMBER 2020 Ready for Boarding! Late 1960s Combined Super Chief – El Capitan see page 4 for details FLYER SALE ENDS 9-30-20 Find a Hobby Shop Near You! Visit walthers.com or call 1-800-487-2467 WELCOME CONTENTS Chill out with cool new products, great deals and WalthersProto Super Chief/El Capitan Pages 4-7 Rolling Along & everything you need for summer projects in this issue! Walthers Flyer First Products Pages 8-10 With two great trains in one, reserve your Late 1960s New from Walthers Pages 11-17 Going Strong! combined Super Chief/El Capitan today! Our next HO National Model Railroad Build-Off Pages 18 & 19 Railroads have a long-standing tradition of getting every last WalthersProto® name train features an authentic mix of mile out of their rolling stock and engines. While railfans of Santa Fe Hi-Level and conventional cars - including a New From Our Partners Pages 20 & 21 the 1960s were looking for the newest second-generation brand-new model, new F7s and more! Perfect for The Bargain Depot Pages 22 & 23 diesels and admiring ever-bigger, more specialized freight operation or collection, complete details start on page 4. Walthers 2021 Reference Book Page 24 cars, a lot of older equipment kept rolling right along. A feature of lumber traffic from the 1960s to early 2000s, HO Scale Pages 25-33, 36-51 Work-a-day locals and wayfreights were no less colorful, the next run of WalthersProto 56' Thrall All-Door Boxcars N Scale Pages 52-57 with a mix of earlier engines and equipment that had are loaded with detail! Check out these layout-ready HO recently been repainted and rebuilt. -

EMD E8 A-A Diesel

2010 volume 2 - part1.qxp 4/9/2010 12:20 PM Page 24 Features - Colorful Paint Scheme EMD E8 A-A Diesel Set - Metal Chassis - Metal Wheels, Axles and Gears - Die-Cast Truck Sides, Pilots and Fuel Tank - (2) Precision Flywheel- Equipped Motors - Intricately Detailed ABS Bodies - (2) Remotely Controlled Proto-Couplers™ - Directionally Controlled Headlight - Metal Horn - Locomotive Speed Control In Scale MPH Increments - Proto-Sound 2.0 With The Digital Command System Featuring Passenger Station Proto-Effects - Unit Measures: 29 3/4” x 2 1/2” x 3 1/2” - Operates On O-31 Curves B-Unit Features - Intricately Detailed ABS Body - Metal Wheels and Axles - Colorful Paint Scheme - Die-Cast Truck Sides - Metal Chassis - Metal Horn - Unit Measures: 13 1/2” x 2 1/2” x 3 1/2” - Operates On O-31 Curves 24 2010 volume 2 - part1.qxp 4/9/2010 12:20 PM Page 25 In the mid-1930's, as the Electro-Motive Division of General Motors was trying to inter- est railroads in diesel passenger power, it experimented a lot with exterior design. Looking at EMD's worm-like yellow and brown Union Pacific M-10000, its gleaming stainless steel Burlington Zephyr, or the boxy, Amtrak - E8 A-A Diesel Engine Set just-plain-ugly early Santa Fe units, it's appar- 30-2996-1 w/Proto-Sound 2.0 $349.95 Add a Matching ent that here was a new function looking for Amtrak - E8 B-Unit Passenger Set 30-2996-3 Non-Powered $119.95 its form. The first generation of road diesels See Page 48 found its form in 1937 when the initial E- units, built for the B&O, inaugurated the clas- sic "covered wagon" cab unit design that would last for decades on both freight and passenger diesels. -

Tlle Llotbox Youtla Model Railroading at It~ Finest!

TllE llOTBOX Youtla Model Railroading at it~ Finest! June 2()()1 l§§Ue jfJ-47 1l'hls Ke11tit: fta Alce PA llNSP Ill Naw Kexice Altd much merer I'll• .,,IJCIAI l'fl811CAf11JOM ., I'll• f'••M ASSOCIAl'IOlt ., MO••I aAIMIOAlt•U The HotBox On the Cover: P A4s 16 and 18 at the BNSF yard in Phoenix, Arizona on March 7, 2000.Nick Olek photo June 2001 (Inset) Minnesota Commercial RS27 318 idles in the back lot of their large Issue 347 roundhouse in the Midway District in St Paul, MN. Seen on July 23, 1999. Andy Inserra photo. Send Articles to: Charles Warczinsk:y 389 Gates Rd Sandusky MI 484 71 Editor: Charles W arczinsk:y [email protected] Inside this Issue: Layout Design Artist: Features: Andy Inserra • Land ofEnchantment -BNSF style Page6 Andy [email protected] • The Alco PA Page 13 • Photo Gallery Page 15 Contributions I Columns: We always need contributions in all forms. Please send the • Top7 Page 5 following in if you wish for the • LOASSB Page 10 staff to consider for an upcoming issue of The Hotbox. Departments: Feature Articles: • Directory Page3 This is what we really need. They • From the Tower Page4 can be from a half page to two • A word from the Editor Page 5 pages typed on anything related • A word from the Layout Design Artist Page5 to railroading, railfanning, model • Events Calendar Page 11 railroading, you get the idea. Page 12 Accompanying pictures are also • TAMR on the Web welcome. Columns: Another thing we can always use! If you wish to start one, please drop us a line. -

Emd 710 Series Engine Benefits Engines 710 Series Engines

EMD 710 SERIES ENGINE BENEFITS ENGINES 710 SERIES ENGINES • Superior reliability means the 710 engine can operate more than • Low lube oil consumption and oil changes based on three years without experiencing a road failure, setting the bar for scheduled sampling the rail industry • Quickly reaches full power providing superior adhesion control • Lightweight, medium-speed engine during wheel slip events for AC freight locomotives • Custom design and integration for optimized performance • Robust, service-proven design with unmatched durability across a wide range of operating environments • Largest installed fleet and common parts provide reduced material, • Inherently emissions friendly and fuel efficient labor, tooling and training costs • Ease of maintenance and lower overhaul costs • New EMD engine technologies can be retrofit on existing models to further enhance performance and efficiency EMD 710 SERIES ENGINE SPECIFICATIONS WORLD-CLASS RELIABILITY ENGINE DESIGNATION 8-710 12-710 16-710 20-710 Sets the rail industry standard for mean time between road failures Cylinders, Arrangement 8 cylinders, 45°V 12 cylinders, 45°V 16 cylinders, 45°V 20 cylinders, 45°V Bore Diameter 230.2 mm (9.1 in) 230.2 mm (9.1 in) 230.2 mm (9.1 in) 230.2 mm (9.1 in) LEADING SUSTAINABILITY AND EFFICIENCY Piston Stroke 279.4 mm (11 in) 279.4 mm (11 in) 279.4 mm (11 in) 279.4 mm (11 in) Meets emissions standards while providing optimized fuel efficiency and reduced lube oil consumption Full-Load Speed 900 rpm 900 rpm 950 rpm 900 rpm Power Rating 1,640 kW (2,200 -

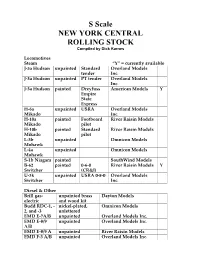

NYC Locos in S

S Scale NEW YORK CENTRAL ROLLING STOCK Compiled by Dick Karnes Locomotives Steam “Y” = currently available J-3a Hudson unpainted Standard Overland Models tender Inc. J-3a Hudson unpainted PT tender Overland Models Inc. J-3a Hudson painted Dreyfuss American Models Y Empire State Express H-6a unpainted USRA Overland Models Mikado Inc. H-10a painted Footboard River Raisin Models Mikado pilot H-10b painted Standard River Raisin Models Mikado pilot L-3b unpainted Omnicon Models Mohawk L-4a unpainted Omnicon Models Mohawk S-1b Niagara painted SouthWind Models B-62 painted 0-6-0 River Raisin Models Y Switcher (CR&I) U-3k unpainted USRA 0-8-0 Overland Models Switcher Inc. Diesel & Other Brill gas- unpainted brass Dayton Models electric and wood kit Budd RDC-1, - nickel-plated, Omnicon Models 2, and -3 unlettered EMD E-7A/B unpainted Overland Models Inc. EMD E-8/9 unpainted Overland Models Inc. A/B EMD E-8/9 A unpainted River Raisin Models EMD F-3 A/B unpainted Overland Models Inc. EMD FT A/B unpainted Overland Models Inc. EMD F-3 A/B painted/freight S Helper Service EMD F-3 A/B painted/passenger S Helper Service EMD F-7 A/B painted/freight S Helper Service EMD F-7 A/B unpainted River Raisin Models EMD F-7 A/B painted/passenger S Helper Service EMD GP-18 painted American Models Y EMD NW-2 unpainted pewter Railmaster Y kit EMD NW-2 unpainted Oriental Models EMD SW-1 unpainted Oriental Models EMD SW-7 unpainted Oriental Models EMD SW-7 unpainted pewter Railmaster Y kit EMD SW-9 painted S Helper Service EMD SW-9 unpainted Oriental Models EMD SW-1200 unpainted Oriental Models Alco RS-1 unpainted brass Locomotive Workshop kit Alco RS-1 unpainted pewter Railmaster Y kit Alco RS-2 unpainted pewter Railmaster Y kit Alco RS-3 painted/freight American Models Y Alco RS-3 unpainted Alco Models Alco RS-3 unpainted pewter Railmaster Y kit Alco S-2 unpainted pewter Railmaster Y kit Alco S-2 unpainted brass Overland Models Inc. -

Rmj 199910.Pdf

The EMD SD40·2 PRECISION RAILROAD MODELS Early Production Version HO Scale model pictured. N scale truck sideframes will differ. ThisHE workhorseEMD SD40-2 is onewill of runthe landmarklike a thoroughbred and pull like a mule! diesel locomotives in railroading history. EMD SD40·2 Diesel Locomotive TheT Early Production version of the locomotive Early Production Version N Scale first rolled onto the rails in January of 1972, and Item # Roadname Road # many of those original units are still in service Without Dynamic Brakes today. 176-4701 Canadian National 5931 176-4702 Canadian National 5934 Now, KATO Precision Railroad Models 176-4705 Union Pacific 4202 will recreate the Early Production version of the 176-4706 Union Pacific 4213 SD40-2 in N scale. 176-4700 Undecorated These models will be equipped with the With Dynamic Brakes world-renowned dual brass flywheel motor and 176-4801 Burlington Northern 6333 frictionless, all-wheel electrical pickup trucks 176-4802 Burlington Northern 6363 KATO is famous for. The split, all-lJIetal chassis 176-4803 Chicago & North Western 6910 provides plenty of weight for powerful tractive 176-4804 Chicago & North Western 6922 effort and will be designed for the easy 176-4805 CSX 8186 installation of a Dee decoder. 176-4806 CSX 8204 The semi-automatic KATO couplers, 176-4807 EMD Leasing 6047 directional lighting and accurate recreation of 176-4808 Milwaukee Road 149 prototype paint schemes will further enhance 176-4809 Milwaukee Road 160 the beauty of the beasts. Seven popular liveries 176-4810 Norfolk Southern 6142 will be recreated, including the versatile EMD 176-4811 Norfolk Southern 6152 Leasing. -

Car & Locomotive Shop

ScaleScale OOTraiTraiTrainsnsns O ◆◆ ◆◆ Jan/FebJan/Feb 2004 2004 IIssuessue #12 #12 $5.95$5.95 US $5.95.95 • Can $7.95.95 Display until Feb. 29th Modeling for the O Scale Craftsman 31280 Groesbeck, Fraser, MI 48026 586-296-6116 Open Mon-Fri 10-8, P&DHobbyHobby ShopShop Sat 10-6, Sun 12-5 P&D Fax: 586-296-5642 PowerPower oror RepowerRepower KitsKits forfor RedRed CabooseCaboose GPsGPs PDP2201K-Repower kit, Red Caboose GP9, P&D brass EMD Blomberg trucks PDP2200K-Repower Kit, Red Caboose GP9 PDP2201K-Repower Kit, Red Caboose GP9 with with plastic Blomberg trucks...$160.00 P&D brass Blomberg trucks...$200.00 The P&D TWIN TOWER DRIVE for the Red Caboose GP screws that are furnished in the Red Caboose body kit. body kit is functionally equivalent to the P&D power units These P&D Twin Tower Drive kits can also be used to repower already available for the P&D F units, GPs, RSDs, and the existing Red Caboose GPs. Two kits are offered: #PDP2200K has Weaver FAs, FBs, RS-3s and GP-38s. plastic Blomberg trucks, while #PDP2201K features the P&D brass The Red Caboose power kits provide only the necessary Blomberg trucks, which are truly some of the finest trucks on the power related parts to supplement the Red Caboose GP market. Each kit also includes a powerful Pittman motor and all body kit. These power kits fully utilize the underframe the necessary parts to complete the installation. Detailed instruc- (platform), deck, air tanks, fuel tanks, motor mounts and tions are included. -

Cannon Ball Spring 2005

Official Publication of Northeastern Region THE SUNRISE TRAIL DIVISION, INC. National Model Railroad Association VOLUME 35 NUMBER 1 SPRING 2005 MODELING MINEOLA a heavily traveled main, two junctions and a variety of traffic make an old standby a gem to model / WALTER WOHLEKING CONTEMPORARY TRENDS in layout design encourage model railroaders to emu- late a prototype with their selection of loco- motives, cars and scenery, to execute their trackplans with prototype-appropriate Layout Design Elements (LDEs), and to operate according to prototype practices employing staging. Because all of this is a lot easier said than done, result often play lip service to concept, and good intentions metamorphose into a collection of rolling stock lettered for the prototype passing through a fictional location on a route that never existed, all regulated by a fast clock to increase the frequency of train appearances and operating interest. Make no mistake about it. This can be a formula for a very satisfying model rail- roading experience. But if emulating the prototype is really what is desired, then it can also be a stretch. Model railroading is truly the art of compromise, and as its prac- titioners model railroaders daily face that challenge from concept through construc- tion to operation of their creations. If truth be told, however, the universal aim of rail- road modelers everywhere is to find a rea- son for as many different locomotives as possible with as many different consists as possible to have as many different things to do as often as possible on their layouts. Without heavily massaging reality, most Few pictures better illustrate Mineola’s modeling potential than this 1953 photograph by William prototypes don't cooperate much toward E. -

Locomotive Cooling Water Temperatures

LOCOMOTIVE COOLING WATER TEMPERATURES An engineman's guide to proper control of engine cooling systems and maintaining optimum cooling temperatures during standard operation of locomotives. This document is intended as a guide and reference of locomotive engine cooling water temperatures. All attempts shall be made to make clear the various key temperatures, when and how they should be achieved, as well as the various terms used throughout the document. The astute engineman reading this document may note that certain themes, subjects and terms are repeated throughout. This is quite intentional, and serves to increase exposure of subject material for attempted retainment by the subject. In addition to cooling water temperatures, there will be included a section regarding the draining of the air reservoirs on page four [4]. Terms, Definitions, and Explanations During the course of this document there will be some terms used which may cause confusion as to what they infer. To avoid undue confusion said terms shall be listed and defined below, and some may include exceptions and/or informative additions on a case by case basis as they apply to certain locomotives. There will also be a basic overview of how the diesel prime mover and it's cooling system work. The engineman should come to know these terms and the applicable definitions, as well the various important differences between locomotives for which exceptions may apply. Load: Increasing the amount of work required of an engine. This is more or less when you place the locomotive in "run" and apply power via the throttle whilst a direction is selected with the reverser. -

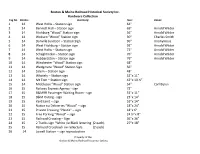

Station Sign 64” 2 14 Bennet

Boston & Maine Railroad Historical Society Inc. Hardware Collection Tag No. File No: Inventory: Size: Donor: 1 14 West Hollis – Station sign 64” 2 14 Bennett Hall – Station sign 69” Arnold Wilder 3 14 Fitchburg “Wood” Station sign 56” Arnold Wilder 4 14 Woburn “Wood” Station sign 30” Charles Smith 5 14 Danville Junction – Station Sign 96” Anonymous 6 14 West Fitchburg – Station sign 92” Arnold Wilder 7 14 West Hollis – Station sign 72” Arnold Wilder 8 14 Scheghticoke – Station sign 76” Arnold Wilder 9 14 Hubbardston – Station sign 76” Arnold Wilder 10 14 Winchester “Wood” Station sign 68” 11 14 Wedgmere “Wood” Station Sign 56” 12 14 Salem – Station sign 48” 13 14 Whately – Station sign 52”x 11” 14 14 Mt Tom – Station sign 42”x 10 ½” 15 14 Middlesex “Wood” Station sign 54” Carl Byron 16 15 Railway Express Agency - sign 72” 17 15 B&MRR Passenger Waiting Room - sign 32”x 11” 18 15 B&M Outing - sign 23”x 14” 19 15 Yard Limit – sign 16”x 14” 20 15 Notice no Deliveries “Wood” – sign 18”x 24” 21 15 Private Crossing “Plastic” – sign 18”x 6” 22 15 Free Parking “Wood” – sign 24 ½”x 8” 23 15 Railroad Crossing – Sign 36”x 36” 24 15 2 Tracks sign “White /w Black lettering (2 each) 27”x 18” 25 15 Railroad Crossbuck /w reflectors (2 each) 26 14 Lowell Station – sign reproduction Property of the Boston & Maine Railroad Historical Society Boston & Maine Railroad Historical Society Inc. Hardware Collection Tag No. File No: Inventory: Size: Donor: 27 15 Hand Held Stop – sign Donald S. -

Proto-Sound 3.0

2014 HO MODEL TRAINS Proto-Sound® 3.0... THE RICHEST SET OF FEATURES IN MODEL RAILROADING! Whether you operate with a conventional transformer or in com- GREAT SMOKE They’ll run in perfect synchronization with each other at any mand mode with DCC or DCS™ (M.T.H.’s Digital Command Sys- Proto-Sound engines feature fan-driven ProtoSmoke™, the most speed. You can even set your lashup so only the lead engine’s tem), the Proto-Sound 3.0 system available in every locomotive in powerful smoke system in the hobby. You can vary the intensity bell and whistle will sound, as in real life multiple-unit operation. this catalog offers more realism, more fun, and more variety than with the smoke “volume” control on the locomotive or remotely any other locomotive control system in any scale. with any DCC or DCS controller. DCC Features VIVID ENGINE SOUNDS SYNCHRONIZED CHUFF AND PUFF Proto-Sound 3.0-equipped locomotives can be controlled in com- Proto-Sound features crystal-clear digital sounds. We strive to mand mode with any DCC-compliant command control system. Like a real steam engine, M.T.H. steamers feature puffs of smoke While you won’t have access to all of the incredible features of make our sounds as authentic as possible, using the charac- and steam chuff sounds synchronized with the drive wheels. Bet- Proto-Sound 3.0, you will have full DCC command control. This teristic whistle for a particular steam engine, for example. With ter than any other model train, an M.T.H. -

16-36 Compressed Natural Gas Short Line Locomotive Study

You can slide the agency groupings to the left as neccessary to accomodate a larger name Compressed Natural Gas Short Line Locomotive Study Final Report DecemberDecember 2016 2016 ReportReport N Numberumber 16-36 16-19 Cover Image: Courtesy of Energetics Incorporated Compressed Natural Gas Short Line Locomotive Study Final Report Prepared for: New York State Energy Research and Development Authority Albany, NY Joseph Tario Senior Project Manager and New York State Department of Transportation Albany, NY Mark Grainer Project Manager Prepared by: Genesee Valley Transportation Company Batavia, NY Greg Cheshier President and Energetics Incorporated Clinton, NY Bryan Roy Principal Engineer NYSERDA Report 16-36 NYSERDA Contract 46832 December 2016 Notice This report was prepared by Genesee Valley Transportation Company and Energetics Incorporated (hereafter the "Contractors") in the course of performing work contracted for and sponsored by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority and the New York State Department of Transportation (hereafter the "Sponsors"). The opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect those of the Sponsors or the State of New York, and reference to any specific product, service, process, or method does not constitute an implied or expressed recommendation or endorsement of it. Further, the Sponsors, the State of New York, and the contractor make no warranties or representations, expressed or implied, as to the fitness for particular purpose or merchantability of any product, apparatus,