JAYNE COUNTY: Paranoia Paradise | the Brooklyn Rail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unobtainium-Vol-1.Pdf

Unobtainium [noun] - that which cannot be obtained through the usual channels of commerce Boo-Hooray is proud to present Unobtainium, Vol. 1. For over a decade, we have been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We invite you to our space in Manhattan’s Chinatown, where we encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections by appointment or chance. Please direct all inquiries to Daylon ([email protected]). Terms: Usual. Not onerous. All items subject to prior sale. Payment may be made via check, credit card, wire transfer or PayPal. Institutions may be billed accordingly. Shipping is additional and will be billed at cost. Returns will be accepted for any reason within a week of receipt. Please provide advance notice of the return. Please contact us for complete inventories for any and all collections. The Flash, 5 Issues Charles Gatewood, ed. New York and Woodstock: The Flash, 1976-1979. Sizes vary slightly, all at or under 11 ¼ x 16 in. folio. Unpaginated. Each issue in very good condition, minor edgewear. Issues include Vol. 1 no. 1 [not numbered], Vol. 1 no. 4 [not numbered], Vol. 1 Issue 5, Vol. 2 no. 1. and Vol. 2 no. 2. Five issues of underground photographer and artist Charles Gatewood’s irregularly published photography paper. Issues feature work by the Lower East Side counterculture crowd Gatewood associated with, including George W. Gardner, Elaine Mayes, Ramon Muxter, Marcia Resnick, Toby Old, tattooist Spider Webb, author Marco Vassi, and more. -

Reinblättern (Pdf)

Philipp Meinert Von den Sechzigern bis in die Gegenwart Philipp Meinert, 1983 ausgerechnet in Gladbeck geboren, erlebte im Ruhrgebiet eine solide Punksozialisation. Inhalt Studium der Sozialwissenschaften in Bochum. Seit 2010 neben seiner Lohnarbeit regelmäßiger Schreiber und Interviewer für verschiedene Online- und Print- medien, hauptsächlich für das »Plastic Bomb Fanzine«. Über dieses Buch und Einleitung ...................................... 9 2013 gemeinsam mit Martin Seeliger Herausgeber des Sammelbandes »Punk in Deutschland. Sozial- und kultur- »A walk on the wild side« 15 wissenschaftliche Per spektiven«. Lebt in Berlin. Die ziemlich queere Welt des Prä-Punks in New York ................... Lou Reed: Der bisexuelle Pate des Punk .................................. 17 Glam: Glitzernde Vorzeichen des Punk .................................. 25 »Personality Crisis« Die New York Dolls als Bindeglied 30 zwischen Punk und Glam ............................................. »Hey little Girl! I wanna be your boyfriend.« Mit den Ramones 35 wird es heterosexueller................................................ »Immer der coolste Typ im Raum« - Interview Danny Fields ............... 38 »Man Enough To Be a Woman« – Jayne County, die transsexuelle 44 Punkgeburtshelferin ................................................... Punk-Genese in England .............................................. 57 Die englische Punkrevolution als kreative Befreiung von Frauen ............. 67 Interview mit Bertie Marshall ......................................... -

Ramones 2002.Pdf

PERFORMERS THE RAMONES B y DR. DONNA GAINES IN THE DARK AGES THAT PRECEDED THE RAMONES, black leather motorcycle jackets and Keds (Ameri fans were shut out, reduced to the role of passive can-made sneakers only), the Ramones incited a spectator. In the early 1970s, boredom inherited the sneering cultural insurrection. In 1976 they re earth: The airwaves were ruled by crotchety old di corded their eponymous first album in seventeen nosaurs; rock & roll had become an alienated labor - days for 16,400. At a time when superstars were rock, detached from its roots. Gone were the sounds demanding upwards of half a million, the Ramones of youthful angst, exuberance, sexuality and misrule. democratized rock & ro|ft|you didn’t need a fat con The spirit of rock & roll was beaten back, the glorious tract, great looks, expensive clothes or the skills of legacy handed down to us in doo-wop, Chuck Berry, Clapton. You just had to follow Joey’s credo: “Do it the British Invasion and surf music lost. If you were from the heart and follow your instincts.” More than an average American kid hanging out in your room twenty-five years later - after the band officially playing guitar, hoping to start a band, how could you broke up - from Old Hanoi to East Berlin, kids in full possibly compete with elaborate guitar solos, expen Ramones regalia incorporate the commando spirit sive equipment and million-dollar stage shows? It all of DIY, do it yourself. seemed out of reach. And then, in 1974, a uniformed According to Joey, the chorus in “Blitzkrieg Bop” - militia burst forth from Forest Hills, Queens, firing a “Hey ho, let’s go” - was “the battle cry that sounded shot heard round the world. -

Christian Ricci Behind the Scenes in New York – Fall 2020 Assignment #1 October 05, 2020 1 Opened in 1973 on Bowery in Manhatt

Christian Ricci Behind the Scenes in New York – Fall 2020 Assignment #1 October 05, 2020 Opened in 1973 on Bowery in Manhattan’s East Village, CBGB was a bar and music venue which features prominently in the history of American punk rock, New Wave and Hardcore music genres. The club’s owner, Hilly Kristal, was always involved with music and musicians, having worked as a manager at the legendary jazz club Village Vanguard booking acts like Miles Davis. When CBGB first opened its doors in the early seventies the venue featured mostly country, blue grass, and blues acts (thus CBGB) before transitioning over to punk rock acts later in the decade. Many well know performers of the punk rock era received their start and earliest exposure at the club, including the Ramones, Patti Smith, Television, Blondie, and Joan Jett. During the New Wave era, performers like Elvis Costello, Talking Heads and even early performances from the Police graced the stage in the now legendary venue. Located at 315 Bowery, which is situated near the northern section of Bowery before it splits into 3rd and 4th Avenues at Cooper square, the original building on the site was constructed in 1878 and was used as a tenement house for 10 families with a shop (liquor store) on the ground floor. In 1934, 315 and 313 were combined into one building and the façade was redesigned and constructed in the Art Deco style, as documented in the 1940 tax photo. At that time, the building was occupied by the Palace Hotel with a ground floor saloon. -

The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew Hes Ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1996 "I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew heS ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Ames, Matthew Sheridan, ""I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade." (1996). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6150. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6150 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Jayne County Paranoia Paradise Curated by Michael Fox February 4 – March 11, 2018 Opening Reception, Sunday, February 4, 7-9Pm

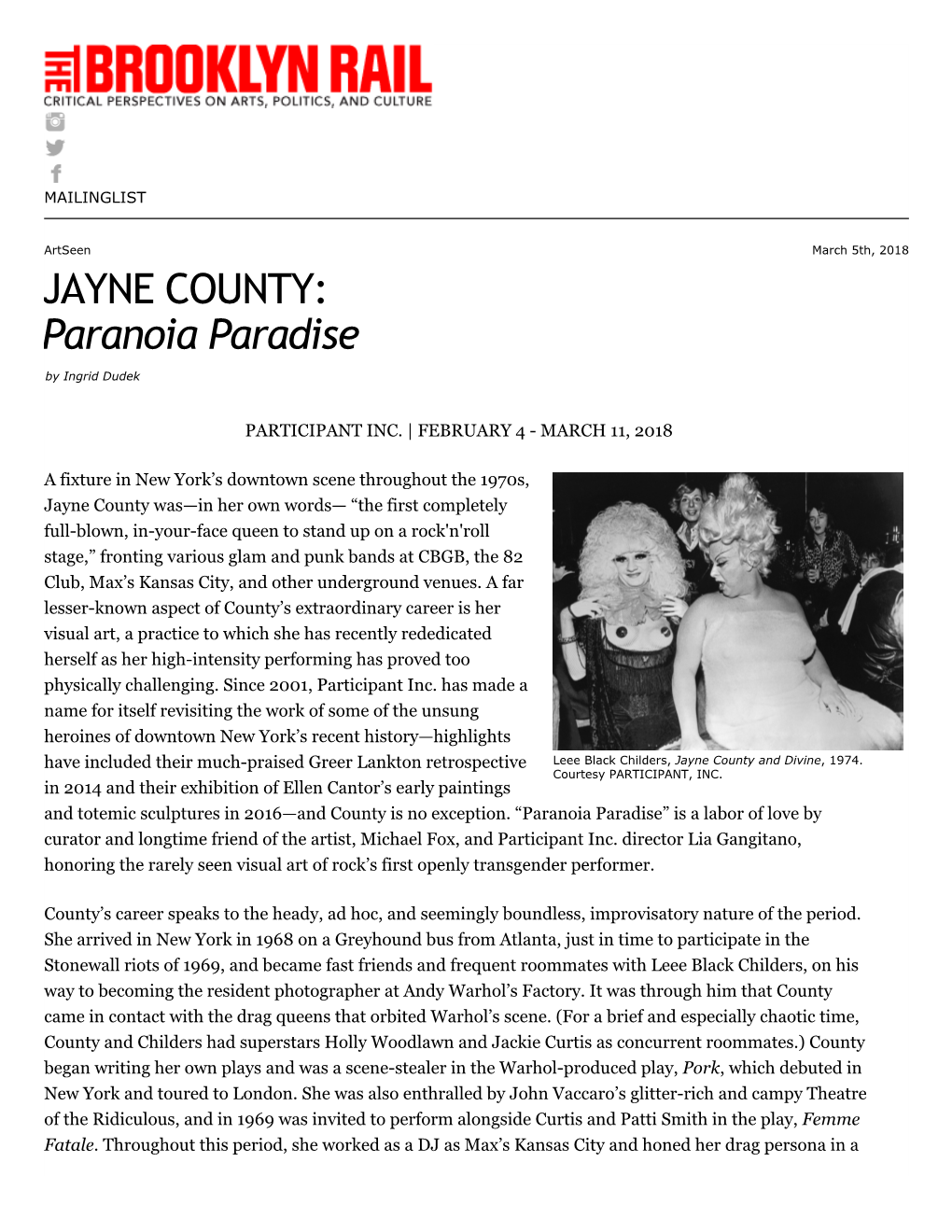

For Immediate Release contact [email protected], 646-492-4076 Jayne County Paranoia Paradise Curated by Michael Fox February 4 – March 11, 2018 Opening Reception, Sunday, February 4, 7-9pm I think that my art serves as a way of putting out the fuse before it becomes a ballistic bomb of some sort. Some people are at odds with the world and they become serial killers, and others become artists. –Jayne County From February 4 – March 11, 2018, PARTICIPANT INC is honored to present Jayne County, Paranoia Paradise, the first retrospective exhibition of County’s visual artwork, curated by Michael Fox. Although County’s artistic output began in experimental theater in the late 1960s-early ‘70s, including work with Theater of the Ridiculous and in Andy Warhol’s Pork, she is perhaps most well-known as a rock singer and performer. This exhibition takes its title from one of County’s songs, Paranoia Paradise, which she famously performed as the character of “Lounge Lizard” in Derek Jarman’s 1978 film, Jubilee. Selections of her earliest known paintings and works on paper made in the early ‘80s while living in Berlin will be exhibited alongside works made up until the present, with approximately eighty pieces on view from County’s studio as well as several private collections. A presentation of related ephemeral materials from County’s archive, as well as photographs by Bob Gruen, Leee Black Childers, and Michael Fox will accompany the exhibition and further illuminate her legendary contributions to music, film, performance, as well her role as forebear and gender pioneer as the first openly transgender rock performer. -

From Vintage Collectors and Mixology Fans to Surf, Rockabilly and Punk Music Scenesters, the Escapist Vibes of the Tiki Scene Still Have a Strong Hold on Los Angeles

THE BEST TIKI DRINKS REVISITING GORDON PARKS’ CONTROVERSIAL PHOTO ESSAY TV’S FUTURE IS FEMALE ® AUGUST 2-8, 2019 / VOL. 41 / NO.37 / LAWEEKLY.COM From vintage collectors and mixology fans to surf, rockabilly and punk music scenesters, the escapist vibes of the tiki scene still have a strong hold on Los Angeles. And at Tiki Oasis in San Diego, everyone comes out to play. BY LINA LECARO 2 WEEKLY WEEKLY LA | A - , | | A WWW.LAWEEKLY.COM Welcome to the New Normal Experience life in the New Normal today. Present this page at any MedMen store to redeem this special offer. 10% off your purchase CA CA License A10-17-0000068-TEMP For one-time use only, redeemable until 06/30/19. Limit 1 per customer. Cannot be combined with any other offers. PAID ADVERTISEMENT 3 LA WEEKLY WEEKLY | A - , | | A THANK YOU, SENATOR DURAZO, FOR PUTTING PEOPLE BEFORE DRUG COMPANY PROFITS. WWW.LAWEEKLY.COM AARP thanks the members of the Senate Judiciary Committee for standing up for Californians and passing AB 824. This legislation would prohibit brand-name drug companies from paying generic manufacturers to delay the release of lower priced drugs. AARP strongly supports this important fi rst step towards ending the anti-competitive practices of big drug companies and lowering prescription drug prices for everyone. Too many people are struggling to make ends meet while the big drug companies continue to rake in billions. AARP encourages the entire Senate to pass AB 824, and put a stop to drug company price gouging. facebook.com/AARPCalifornia @AARPCA AARP.org/CA Paid For by AARP 4 L August 2-8, 2019 // Vol. -

Arrive a Tourist. Leave a Local

TOURS ARRIVE A TOURIST. LEAVE A LOCAL. www.OnBoardTours.com Call 1-877-U-TOUR-NY Today! NY See It All! The NY See It All! tour is New York’s best tour value. It’s the only comprehensive guided tour of shuttle with you at each stop. Only the NY See It All! Tour combines a bus tour and short walks to see attractions with a boat cruise in New York Harbor.Like all of the NYPS tours, our NY See It All! Our guides hop o the shuttle with you at every major attraction, including: START AT: Times Square * Federal Hall * World Trade Ctr. Site * Madison Square Park * NY Stock Exchange * Statue of Liberty * Wall Street (viewed from S. I. Ferry) * St. Paul’s Chapel * Central Park * Trinity Church * Flatiron Building * World Financial Ctr. * Bowling Green Bull * South Street Seaport * Empire State Building (lunch cost not included) * Strawberry Fields * Rockefeller Center and St. Patrick's Cathedral In addition, you will see the following attractions along the way: (we don’t stop at these) * Ellis Island * Woolworth Building * Central Park Zoo * Met Life Building * Trump Tower * Brooklyn Bridge * Plaza Hotel * Verrazano-Narrows Bridge * City Hall * Hudson River * Washington Square Park * East River * New York Public Library * FAO Schwarz * Greenwich Village * Chrysler Building * SOHO/Tribeca NY See The Lights! Bright lights, Big City. Enjoy The Big Apple aglow in all its splendor. The NY See The Lights! tour shows you the greatest city in the world at night. Cross over the Manhattan Bridge and visit Brooklyn and the Fulton Ferry Landing for the lights of New York City from across the East river. -

Robfreeman Recordingramones

Rob Freeman (center) recording Ramones at Plaza Sound Studios 1976 THIRTY YEARS AGO Ramones collided with a piece of 2” magnetic tape like a downhill semi with no brakes slamming into a brick wall. While many memories of recording the Ramones’ first album remain vivid, others, undoubtedly, have dulled or even faded away. This might be due in part to the passing of years, but, moreover, I attribute it to the fact that the entire experience flew through my life at the breakneck speed of one of the band’s rapid-fire songs following a heady “One, two, three, four!” Most album recording projects of the day averaged four to six weeks to complete; Ramones, with its purported budget of only $6000, zoomed by in just over a week— start to finish, mixed and remixed. Much has been documented about the Ramones since their first album rocked the New York punk scene. A Google search of the Internet yields untold numbers of web pages filled with a myriad of Ramones facts and an equal number of fictions. (No, Ramones was not recorded on the Radio City Music Hall stage as is so widely reported…read on.) But my perspective on recording Ramones is unique, and I hope to provide some insight of a different nature. I paint my recollections in broad strokes with the following… It was snowy and cold as usual in early February 1976. The trek up to Plaza Sound Studios followed its usual path: an escape into the warm refuge of Radio City Music Hall through the stage door entrance, a slow creep up the private elevator to the sixth floor, a trudge up another flight -

June-Oct 2021

JUNE-OCT FREE & BENEFIT 2021 PERFORMANCES SUMMERSTAGE.ORG SUMMERSTAGE NYCSUMMERSTAGE SUMMERSTAGENYC SUMMERSTAGE IS BACK More than a year after the first lockdown order, SummerStage is back, ready to once again use our city’s parks as gathering spaces to bring diverse and thriving communities together to find common ground through world-class arts and culture. We are committed to presenting a festival fully representing the city we serve - a roster of diverse artists, focused on gender equity and presenting distinct New York genres. This year, more than ever before, our festival will focus on renewal and resilience, reflective of our city and its continued evolution, featuring artists that are NYC-born, based, or inextricably linked to the city itself. Performers like SummerStage veteran Patti Smith, an icon of the city’s resilient rebelliousness, Brooklyn’s Antibalas, who have married afrobeat with New York City’s Latin soul, and hip hop duo Armand Hammer, two of today’s most important leaders of New York’s rap underground. And, as a perfect symbol of rebirth, Sun Ra’s Arkestra returns to our stage in this year of reopening, 35 years after they performed our very first concert, bringing their ethereal afro-futurist cosmic jazz vibes back to remind us of our ongoing mission and purpose. Our festival art this year also reflects our outlook -- bold, bright, powerful -- and was created by New Yorker Lyne Lucien, an award-winning Haitian artist based in Brooklyn. Lucien is an American Illustration Award Winner and a finalist for the Artbridge - Not a Monolith Residency. She has worked as a photo editor and art director at various publications including New York Magazine, The Daily Beast and Architectural Digest. -

Wr: Mysteries of the Organism Beyond the Liberation of Desire

“THERE IS NOTHING IN THIS HUMAN WORLD OF OURS THAT IS NOT IN SOME WAY RIGHT, HOWEVER DISTORTED IT MAY BE.” WR: MYSTERIES OF THE ORGANISM BEYOND THE LIBERATION OF DESIRE Anarchism, crushed throughout most of the world by the middle of the 20th century, sprang back to life in a variety of different settings. In the US, it reappeared among activists like the Yippies; in Britain, it reemerged in the punk counterculture; in Yugoslavia, where an ersatz form of “self-management” in the workplace was the official program of the communist party, it appeared in a rebel filmmaking movement, the Black Wave. As historians of anarchism, we concern ourselves not only with conferences and riots but also with cinema. Of all the works of the Black Wave, Dušan Makavejev’s WR: Mysteries of the Organism stands out as an exemplary anarchist film. Rather than advertising anarchism as one more product in the supermarket of ideology, it demonstrates a method that undermines all ideologies, all received wisdom. It still challenges us today. up among his workers with his long hair, they would throw him out head first. Even after this debate, the Commission for Cinematography allowed the The struggle of communist partisans against the Nazi occupation provided film, but the public prosecutor banned it the following month. The ban the foundational mythos for 20th-century Yugoslavian national identity. was lifted only in 1986. After the Second World War, the Yugoslavian state poured millions into “I’ve been to the East, and I’ve been to the West, but it was never partisan blockbusters like Battle of Neretva and other sexless paeans to patri- 3. -

Andy Warhol's Factory People

1 Andy Warhol’s Factory People 100 minute Director’s Cut Feature Documentary Version Transcript Opening Montage Sequence Victor Bockris V.O.: “Drella was the perfect name for Warhol in the sixties... the combination of Dracula and Cinderella”. Ultra Violet V.O.: “It’s really Cinema Realité” Taylor Mead V.O.:” We were ‘outré’, avant garde” Brigid Berlin V.O.: “On drugs, on speed, on amphetamine” Mary Woronov V.O.: “He was an enabler” Nico V.O.:” He had the guts to save the Velvet Underground” Lou Reed V.O.: “They hated the music” David Croland V.O.: “People were stealing his work left and right” Viva V.O.: “I think he’s Queen of the pop art.” (laugh). Candy Darling V.O.: “A glittering façade” Ivy Nicholson V.O.: “Silver goes with stars” Andy Warhol: “I don’t have any favorite color because I decided Silver was the only thing around.” Billy Name: This is the factory, and it’s something that you can’t recreate. As when we were making films there with the actual people there, making art there with the actual people there. And that’s my cat, Ruby. Imagine living and working in a place like that! It’s so cool, isn’t it? Ultra Violet: OK. I was born Isabelle Collin Dufresne, and I became Ultra violet in 1963 when I met Andy Warhol. Then I turned totally violet, from my toes to the tip of my hair. And to this day, what’s amazing, I’m aging, but my hair is naturally turning violet.