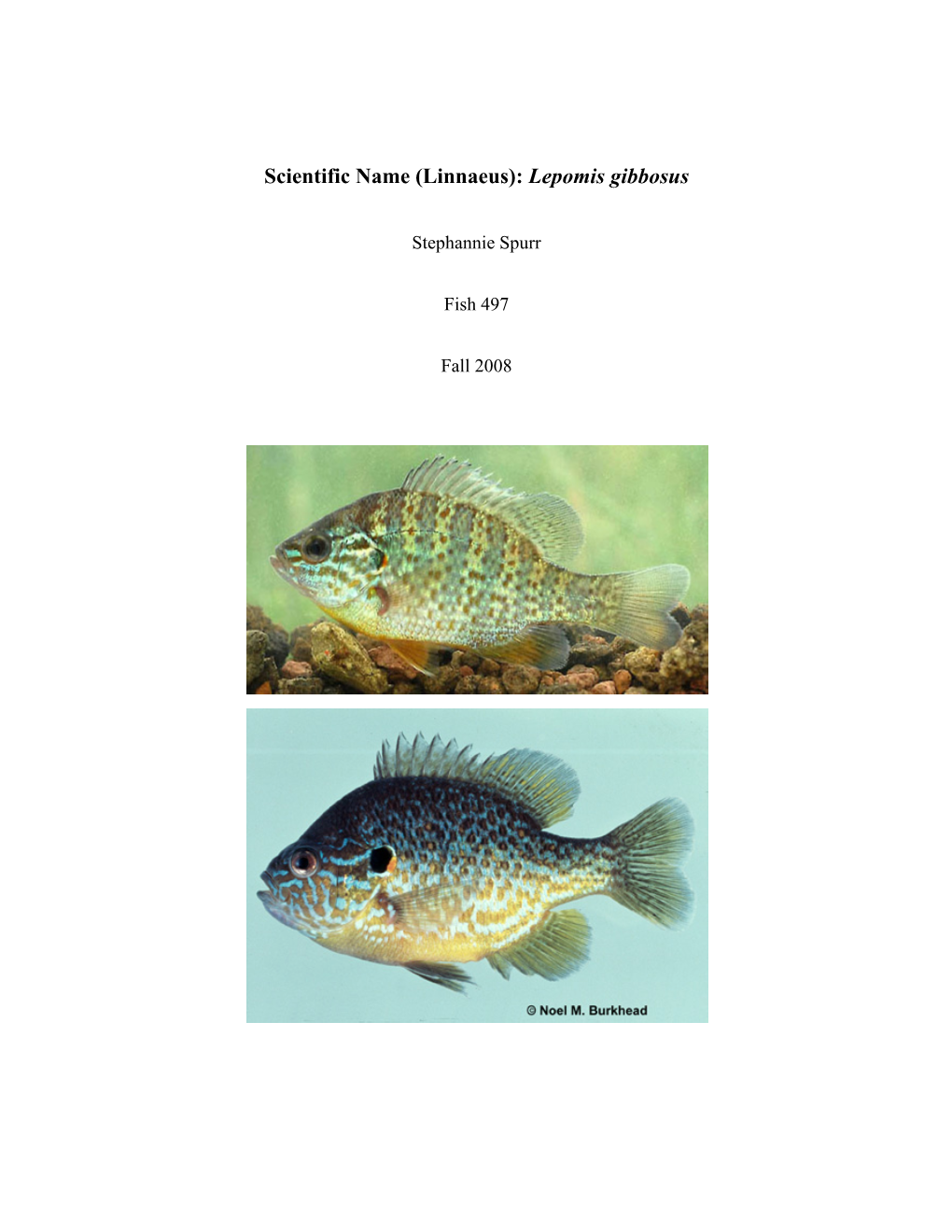

Lepomis Gibbosus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Status Review and Management Outline for Quality Bluegill and Black Crappie Populations in the Grand Rapids Area

Status Review and Management Outline for Quality Bluegill and Black Crappie Populations in the Grand Rapids Area. Revised in 2013 By David L. Weitzel Assistant Area Fisheries Supervisor MN DNR, Grand Rapids Area Fisheries Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Bass Lake ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 Blackwater, Jay Gould, and Little Jay Gould lakes ...................................................................................... 10 Cut Foot and Little Cut Foot Sioux lakes ..................................................................................................... 18 Deer, Pickerel, and Battle lakes .................................................................................................................. 23 Dixon Lake ................................................................................................................................................... 31 Grave Lake ................................................................................................................................................... 37 Split Hand and Little Split Hand Lakes ........................................................................................................ 41 Sand Lake ................................................................................................................................................... -

Peoria Riverfront Development, Illinois (Ecosystem Restoration)

PEORIA RIVERFRONT DEVELOPMENT, ILLINOIS (ECOSYSTEM RESTORATION) FEASIBILITY STUDY WITH INTEGRATED ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT MAIN REPORT MARCH 2003 DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY ROCK ISLAND DISTRICT, CORPS OF ENGINEERS CLOCK TOWER BUILDING - P.O. BOX 2004 ROCK ISLAND, ILLINOIS 61204-2004 REPLY TO ATTENTION OF http://www.mvr.usace.army.mil CEMVR-PM-M PEORIA RIVERFRONT DEVELOPMENT, ILLINOIS (ECOSYSTEM RESTORATION) FEASIBILITY STUDY WITH INTEGRATED ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT MAIN REPORT MARCH 2003 Executive Summary he Peoria Riverfront Development (Ecosystem Restoration) Project area includes Lower Peoria Lake. The area lies within Peoria and Tazewell Counties, Illinois, and includes TIllinois River Miles 162-167. The project is related to the Peoria Riverfront Development Project, a public and private cooperative effort that also includes revitalization of the City’s downtown area. Development includes a visitor’s center, city park, residential redevelopment, community center, riverboat landing, sports complex, entertainment centers, and retail development. The region has begun to reclaim its abandoned industrial riverfront, with the understanding that a healthy, attractive, and sustainable environment must be present. The Illinois River is a symbol of the region’s economic, social, and cultural history, as well as its future. Therefore, ecosystem restoration in Peoria Lake is a vital component to an overall effort and vision to develop the Peoria Riverfront in an ecologically, economically, and socially sustainable manner. This Ecosystem Restoration Feasibility Study was conducted by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Illinois Department of Natural Resources (Non-Federal Sponsor) to investigate the Federal and State interest in ecosystem restoration within Peoria Lake. In support of this resource vision, several regulatory efforts on the part of the cities and counties to address the sedimentation issue affecting the Illinois River have been adopted. -

Variation of the Spotted Sunfish, Lepomis Punctatus Complex

Variation of the Spotted Sunfish, Lepomis punctatus Complex (Centrarehidae): Meristies, Morphometries, Pigmentation and Species Limits BULLETIN ALABAMA MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY The scientific publication of the Alabama Museum of Natural History. Richard L. Mayden, Editor, John C. Hall, Managing Editor. BULLETIN ALABAMA MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY is published by the Alabama Museum of Natural History, a unit of The University of Alabama. The BULLETIN succeeds its predecessor, the MUSEUM PAPERS, which was terminated in 1961 upon the transfer of the Museum to the University from its parent organization, the Geological Survey of Alabama. The BULLETIN is devoted primarily to scholarship and research concerning the natural history of Alabama and the midsouth. It appears irregularly in consecutively numbered issues. Communication concerning manuscripts, style, and editorial policy should be addressed to: Editor, BULLETIN ALABAMA MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY, The University of Alabama, Box 870340, Tuscaloosa, AL 35487-0340; Telephone (205) 348-7550. Prospective authors should examine the Notice to Authors inside the back cover. Orders and requests for general information should be addressed to Managing Editor, BULLETIN ALABAMA MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY, at the above address. Numbers may be purchased individually; standing orders are accepted. Remittances should accompany orders for individual numbers and be payable to The University of Alabama. The BULLETIN will invoice standing orders. Library exchanges may be handled through: Exchange Librarian, The University of Alabama, Box 870266, Tuscaloosa, AL 35487-0340. When citing this publication, authors are requested to use the following abbreviation: Bull. Alabama Mus. Nat. Hist. ISSN: 0196-1039 Copyright 1991 by The Alabama Museum of Natural History Price this number: $6.00 })Il{ -w-~ '{(iI1 .....~" _--. -

Literature Based Characterization of Resident Fish Entrainment-Turbine

Draft Technical Memorandum Literature Based Characterization of Resident Fish Entrainment and Turbine-Induced Mortality Klamath Hydroelectric Project (FERC No. 2082) Prepared for PacifiCorp Prepared by CH2M HILL September 2003 Contents Introduction...................................................................................................................................1 Objectives ......................................................................................................................................1 Study Approach ............................................................................................................................2 Fish Entrainment ..............................................................................................................2 Turbine-induced Mortality .............................................................................................2 Characterization of Fish Entrainment ......................................................................................2 Magnitude of Annual Entrainment ...............................................................................9 Size Composition............................................................................................................10 Species Composition ......................................................................................................10 Seasonal and Diurnal Distribution...............................................................................15 Turbine Mortality.......................................................................................................................18 -

Feeding Tactics and Body Condition of Two Introduced Populations of Pumpkinseed Lepomis Gibbosus: Taking Advantages of Human Disturbances?

Ecology of Freshwater Fish 2009: 18: 15–23 Ó 2008 The Authors Printed in Malaysia Æ All rights reserved Journal compilation Ó 2008 Blackwell Munksgaard ECOLOGY OF FRESHWATER FISH Feeding tactics and body condition of two introduced populations of pumpkinseed Lepomis gibbosus: taking advantages of human disturbances? Almeida D, Almodo´var A, Nicola GG, Elvira B. Feeding tactics and body D. Almeida1, A. Almodo´var1, condition of two introduced populations of pumpkinseed Lepomis G. G. Nicola2, B. Elvira1 gibbosus: taking advantages of human disturbances? 1Department of Zoology and Physical Anthropol- Ecology of Freshwater Fish 2009: 18: 15–23. Ó 2008 The Authors. ogy, Faculty of Biology, Complutense University Journal compilation Ó 2008 Blackwell Munksgaard of Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Castilla-La Mancha, Toledo, Spain Abstract – Feeding tactics, body condition and size structure of two populations of pumpkinseed Lepomis gibbosus from Caban˜eros National Park (Guadiana River basin, central Spain) were compared to provide insight into the ecological requirements favouring levels of success ⁄ failure in relation to human intervention. Habitat, benthic macroinvertebrates and pumpkinseed were quantified in Bullaque (regulated flow, affected by agricultural activities) and Estena (natural conditions) rivers, from May to September of 2005 and 2006. Significant differences were found in the limnological characteristics between the two rivers. Spatial and temporal Key words: invasive species; feeding tactics; prey variations in diet composition were likely related to opportunistic feeding selection; freshwater fishes and high foraging plasticity. Diet diversity was higher in Bullaque River. B. Elvira, Department of Zoology and Physical Electivity of benthic prey showed variation between sized individuals and Anthropology, Faculty of Biology, Complutense populations. -

Influence of Invasive Hybrid Cattails on Habitat Use by Common Loons

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers National Park Service 2018 Influence of Invasive Hybrid Cattails on Habitat Use by Common Loons Spencer L. Wesche Benjamin J. O'Neal Steve K. Windels Bryce T. Olson Max Larreur See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natlpark This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the National Park Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors Spencer L. Wesche, Benjamin J. O'Neal, Steve K. Windels, Bryce T. Olson, Max Larreur, and Adam A. Ahlers Wildlife Society Bulletin 42(1):166–171; 2018; DOI: 10.1002/wsb.863 From The Field Influence of Invasive Hybrid Cattails on Habitat Use by Common Loons SPENCER L. WESCHE, Department of Biology, Franklin College, Franklin, IN 46131, USA BENJAMIN J. O’NEAL, Department of Biology, Franklin College, Franklin, IN 46131, USA STEVE K. WINDELS, National Park Service, Voyageurs National Park, International Falls, MN 56649, USA BRYCE T. OLSON, National Park Service, Voyageurs National Park, International Falls, MN 56649, USA MAX LARREUR, Department of Horticulture and Natural Resources, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66506, USA ADAM A. AHLERS,1 Department of Horticulture and Natural Resources, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66506, USA ABSTRACT An invasive hybrid cattail species, Typha  glauca (T.  glauca), is rapidly expanding across the United States and Canada. -

Labidesthes Sicculus

Version 2, 2015 United States Fish and Wildlife Service Lower Great Lakes Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office 1 Atherinidae Atherinidae Sand Smelt Distinguishing Features: — (Atherina boyeri) — Sand Smelt (Non-native) Old World Silversides Old World Silversides Old World (Atherina boyeri) Two widely separated dorsal fins Eye wider than Silver color snout length 39-49 lateral line scales 2 anal spines, 13-15.5 rays Rainbow Smelt (Non -Native) (Osmerus mordax) No dorsal spines Pale green dorsally Single dorsal with adipose fin Coloring: Silver Elongated, pointed snout No anal spines Size: Length: up to 145mm SL Pink/purple/blue iridescence on sides Distinguishing Features: Dorsal spines (total): 7-10 Brook Silverside (Native) 1 spine, 10-11 rays Dorsal soft rays (total): 8-16 (Labidesthes sicculus) 4 spines Anal spines: 2 Anal soft rays: 13-15.5 Eye diameter wider than snout length Habitat: Pelagic in lakes, slow or still waters Similar Species: Rainbow Smelt (Osmerus mordax), 75-80 lateral line scales Brook Silverside (Labidesthes sicculus) Elongated anal fin Images are not to scale 2 3 Centrarchidae Centrarchidae Redear Sunfish Distinguishing Features: (Lepomis microlophus) Redear Sunfish (Non-native) — — Sunfishes (Lepomis microlophus) Sunfishes Red on opercular flap No iridescent lines on cheek Long, pointed pectoral fins Bluegill (Native) Dark blotch at base (Lepomis macrochirus) of dorsal fin No red on opercular flap Coloring: Brownish-green to gray Blue-purple iridescence on cheek Bright red outer margin on opercular flap -

15 Best Indiana Panfishing Lakes

15 best Indiana panfishing lakes This information has been shared numerous places but somehow we’ve missed putting it on our own website. If you’ve been looking for a place to catch some dinner, our fisheries biologists have compiled a list of the 15 best panfishing lakes throughout Indiana. Enjoy! Northern Indiana Sylvan Lake Sylvan Lake is a 669-acre man made reservoir near Rome City. It is best known for its bluegill fishing with some reaching 9 inches. About one third of the adult bluegill population are 7 inches or larger. The best places to catch bluegill are the Cain Basin at the east end of the lake and along the 8 to 10 foot drop-offs in the western basin. Red-worms, flies, and crickets are the most effective baits. Skinner Lake Skinner Lake is a 125-acre natural lake near Albion. The lake is known for crappie fishing for both black and white crappies. Most crappies are in the 8 to 9 inch range, with some reaching 16 inches long. Don’t expect to catch lots of big crappies, but you can expect to catch plenty that are keeper-size. The best crappie fishing is in May over developing lily pads in the four corners of the lake. Live minnows and small white jigs are the most effective baits. J. C. Murphey Lake J. C. Murphey Lake is located on Willow Slough Fish and Wildlife Area in Newton County. Following this winter, there was minimal ice fishing (due to lack of ice) and the spring fishing should be phenomenal especially for bluegills. -

Wildlife Species

Wildlife Species This chapter contains information on species featured in each of the ecoregions. Species are grouped by Birds, Mammals, Reptiles, Amphibians, and Fish. Species are listed alphabetically within each group. A general description, habitat requirements, and possible wildlife management practices are provided for each species. Wildlife management practices for a particular species may vary among ecoregions, so not all of the wildlife management practices listed for a species may be applicable for that species in all ecoregions. Refer to the WMP charts within a particular ecoregion to determine which practices are appropriate for species included in that ecoregion. The species descriptions contain all the information needed about a particular species for the WHEP contest. However, additional reading should be encouraged for participants that want more detailed information. Field guides to North American wildlife and fish are good sources for information and pictures of the species listed. There also are many Web sites available for wildlife species identification by sight and sound. Information from this section will be used in the Wildlife Challenge at the National Invitational. Participants should be familiar with the information presented within the species accounts for those species included within the ecoregions used at the Invitational. It is important to understand that when assessing habitat for a particular wildlife species and considering various WMPs for recommendation, current conditions should be evaluated. That is, WMPs should be recommended based on the current habitat conditions within the year. Also, it is important to realize the benefit of a WMP may not be realized soon. For example, trees or shrubs planted for mast may not provide cover or bear fruit for several years. -

Fine Structure of the Retina of Black Bass, Micropterus Salmoides (Centrarchidae, Teleostei)

Histol Histopathol (1999) 14: 1053-1065 Histology and 001: 10.14670/HH-14.1053 Histopathology http://www.hh.um.es From Cell Biology to Tissue Engineering Fine structure of the retina of black bass, Micropterus salmoides (Centrarchidae, Teleostei) M. Garcia and J. de Juan Department of Biotechnology, University of Alicante, Alicante, Spain Summary. The structure of light- and dark-adapted 1968), 4) regular cone mosaics (Wagner, 1978), 5) the retina of the black bass, Micropterus salmoides has been existence of a well developed retinal tapetum in studied by light and electron microscopy. This retina nocturnal and bottom-living species (Wagner and Ali, lacks blood vessels at all levels. The optic fiber layer is 1978), 6) presence of foveae or areas with an increase in divided into fascicles by the processes of Muller cells photoreceptors and other neurons (Wagner, 1990), and 7) and the ganglion cell layer is represented by a single row a marked synaptic plasticity as is demonstrated by the of voluminous cells. The inner nuclear layer consists of formation of spinules (Wagner, 1980) during light two layers of horizontal cells and bipolar, amacrine and adaptation and their disappearance during dark interplexiform cells. In the outer plexiform layer we adaptation, and others. In summary, these features observed the synaptic terminals of photoreceptor celis, demonstrate the importance of vision in the mode of life rod spherules and cone pedicles and terminal processes and survival of the species. of bipolar and horizontal cells. The spherules have a Micropterus salmoides, known as black bass, is a single synaptic ribbon and the pedicles possess multiple member of the family Centrarchidae (Order Perciformes) synaptic ribbons. -

4-H-993-W, Wildlife Habitat Evaluation Food Flash Cards

Purdue extension 4-H-993-W Wildlife Habitat Evaluation Food Flash Cards Authors: Natalie Carroll, Professor, Youth Development right, it goes in the “fast” pile. If it takes a little and Agricultural Education longer, put the card in the “medium” pile. And if Brian Miller, Director, Illinois–Indiana Sea Grant College the learner does not know, put the card in the “no” Program Photos by the authors, unless otherwise noted. pile. Concentrate follow-up study efforts on the “medium” and “no” piles. These flash cards can help youth learn about the foods that wildlife eat. This will help them assign THE CONTEST individual food items to the appropriate food When youth attend the WHEP Career Development categories and identify which wildlife species Event (CDE), actual food specimens—not eat those foods during the Foods Activity of the pictures—will be displayed on a table (see Wildlife Habitat Evaluation Program (WHEP) Figure 1). Participants need to identify which contest. While there may be some disagreement food category is represented by the specimen. about which wildlife eat foods from the category Participants will write this food category on the top represented by the picture, the authors feel that the of the score sheet (Scantron sheet, see Figure 2) and species listed give a good representation. then mark the appropriate boxes that represent the wildlife species which eat this category of food. The Use the following pages to make flash cards by same species are listed on the flash cards, making it cutting along the dotted lines, then fold the papers much easier for the students to learn this material. -

GREEN SUNFISH (Lepomis Cyanellus)

GREEN SUNFISH Oneida Lake Status: (Lepomis cyanellus) Not Common • Oneida Lake population small but on the rise • Out competes bluegills in Oneida Lake • Hybridization makes identification difficult Green sunfish may grow to 9 inches in Oneida Lake, and weigh up to a ½ pound. Green sunfish are not as deep bodied as other commonly known sunfish, and typically have a more Green sunfish in the wild: drab color scheme. They have a blue-green back that fades to http://www.bobberstop.com/images/gr yellow or white at the belly, and have a black earflap with a een_sunfish.jpg yellow edge (see drawing). Green sunfish have a top jaw that extends back to the middle of the eye, and a mouth that is larger than its close relatives. Unfortunately, green sunfish may hybridize with pumpkinseed and bluegill sunfish (see photo to left), making identification difficult. Sunfish identification becomes difficult when hybridization occurs: http://www.southernpondsandwildlife.c om/upload/articletitles/000052.50.jpg Small green sunfish before release back to the water: http://www.tnfish.org/PhotoGalleryFish_TWRA/FishPhotoGallery_ TWRA/pages/GreenSunfishMeltonHillNegus_jpg.htm Green sunfish do not favor any bottom type in Oneida Lake, but generally live near brush, vegetation, and rocks. Unlike most sunfish, greens tolerate areas with high turbidity and Line drawing of a green sunfish low dissolved oxygen. In Oneida, green sunfish eat small fish, aquatic insects, and other invertebrates, and their large mouths allow them to eat larger prey than other sunfish can. Prepared by: Green sunfish are found in Oneida Lake and throughout New York State. While it is possible that they are native to Alexander Sonneborn Oneida, green sunfish are an invasive exotic in many places Cornell Biological Field Station and often out-compete the native bluegill.