Pair of Lone Wolves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev Had Murdered Krystle Marie Campbell, Lingzi Lu, Martin Richard, and Officer Sean Collier, He Was Here in This Courthouse

United States Court of Appeals For the First Circuit No. 16-6001 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Appellee, v. DZHOKHAR A. TSARNAEV, Defendant, Appellant. APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS [Hon. George A. O'Toole, Jr., U.S. District Judge] Before Torruella, Thompson, and Kayatta, Circuit Judges. Daniel Habib, with whom Deirdre D. von Dornum, David Patton, Mia Eisner-Grynberg, Anthony O'Rourke, Federal Defenders of New York, Inc., Clifford Gardner, Law Offices of Cliff Gardner, Gail K. Johnson, and Johnson & Klein, PLLC were on brief, for appellant. John Remington Graham on brief for James Feltzer, Ph.D., Mary Maxwell, Ph.D., LL.B., and Cesar Baruja, M.D., amici curiae. George H. Kendall, Squire Patton Boggs (US) LLP, Timothy P. O'Toole, and Miller & Chevalier on brief for Eight Distinguished Local Citizens, amici curiae. David A. Ruhnke, Ruhnke & Barrett, Megan Wall-Wolff, Wall- Wolff LLC, Michael J. Iacopino, Brennan Lenehan Iacopino & Hickey, Benjamin Silverman, and Law Office of Benjamin Silverman PLLC on brief for National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, amicus curiae. William A. Glaser, Attorney, Appellate Section, Criminal Division, U.S. Department of Justice, with whom Andrew E. Lelling, United States Attorney, Nadine Pellegrini, Assistant United States Attorney, John C. Demers, Assistant Attorney General, National Security Division, John F. Palmer, Attorney, National Security Division, Brian A. Benczkowski, Assistant Attorney General, and Matthew S. Miner, Deputy Assistant Attorney General, were on brief, for appellee. July 31, 2020 THOMPSON, Circuit Judge. OVERVIEW Together with his older brother Tamerlan, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev detonated two homemade bombs at the 2013 Boston Marathon, thus committing one of the worst domestic terrorist attacks since the 9/11 atrocities.1 Radical jihadists bent on killing Americans, the duo caused battlefield-like carnage. -

Addressing the Evolving Threat to Domestic Security

CONGRESSIONAL TESTIMONY: FOUNDATION FOR DEFENSE OF DEMOCRACIES House Committee on Homeland Security, Subcommittee on Counterterrorism and Intelligence The Future of Counterterrorism: Addressing the Evolving Threat to Domestic Security THOMAS JOSCELYN Senior Fellow Foundation for Defense of Democracies Senior Editor FDD’s Long War Journal Washington, DC February 28, 2017 www.defenddemocracy.org Thomas Joscelyn February 28, 2017 Chairman King, Ranking Member Rice, and other members of the committee, thank you for inviting me to testify today. The terrorist threat has evolved greatly since the September 11, 2001 hijackings. The U.S. arguably faces a more diverse set of threats today than ever. In my written and oral testimony, I intend to highlight both the scope of these threats, as well as some of what I think are the underappreciated risks. My key points are as follows: • The U.S. military and intelligence services have waged a prolific counterterrorism campaign to suppress threats to America. It is often argued that because no large-scale plot has been successful in the U.S. since 9/11 that the risk of such an attack is overblown. This argument ignores the fact that numerous plots, in various stages of development, have been thwarted since 2001. Meanwhile, Europe has been hit with larger-scale operations. In addition, the U.S. and its allies frequently target jihadists who are suspected of plotting against the West. America’s counterterrorism strategy is mainly intended to disrupt potentially significant operations that are in the pipeline. • Over the past several years, the U.S. military and intelligence agencies claim to have struck numerous Islamic State (or ISIS) and al Qaeda “external operatives” in countries such as Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Pakistan, Syria, Yemen, and elsewhere. -

Lone Wolf Terrorism and Open Source Jihad: an Explanation and Assessment

1 LONE WOLF TERRORISM AND OPEN SOURCE JIHAD: AN EXPLANATION AND ASSESSMENT Claire Wiskind, (Research Assistant, ICT) Summer 2016 ABSTRACT Al Qaeda and Daesh publish English language magazines to appeal to Western supporters and encourage them to join their cause as a fighter or as a lone wolf terrorist. A key feature of Al Qaeda’s magazine, Inspire, is a section titled Open Source Jihad, which provides aspiring jihadists with step-by-step instructions to carry out lone terror attacks in the West. By examining ten attack types that have been published over the past six years, this paper explains Open Source Jihad, presents cases where these types of attacks have been carried out, and assesses the threat presented by the easy access to Open Source Jihad. * The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Institute for Counter-Terrorism (ICT). 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 3 Lone Wolf Terrorism ......................................................................................... 3 English Language Literature: Dabiq and Inspire .............................................. 7 Open Source Jihad .......................................................................................... 9 OPEN SOURCE JIHAD ATTACK INSTRUCTIONS ..................................... 12 Attacks carried out .......................................................................................... -

BOSTON MARATHON BOMBING I. INTRODUCTION on 15 April 2013

BOSTON MARATHON BOMBING I. INTRODUCTION On 15 April 2013 the whole world was shocked by the news of an explosion that occur in Boston. Two bombs occured near the finish line on the spectator side of the Boston Marathon. The explosion killed 3 people, who were spectator and injured many other who attended. The 3 victims who were killed and they are Krystle Campbell, the second victim was an 8 years old child name Martin Richard, and the last victim is a woman name Lu Lingzi who was a Chinese citizen. Around 134 were wounded and 15 of them were seriously injured. Citing from dailymail reports on Tuesday, April 16, 2013 which clearly stated that there were actually seven bombs planted on the occasion . However, only two of them exploded near the finish line with a gap of about 12 seconds. The location of the explosion is only 50 - 100 meters from the finish line. Officers came straight towards the location of the explosion and search for any suspicious objects . At the scene , there were a lot of bags and the equipment of the athlete marathon runner who were abandoned simply because they were rushing to save themselves . The scene was indeed very chaotic. This bombing was sudden, there were no threat before the incident and people were very much unaware that this incident was likely to happen. Therefore, according to the principle of war, this fall under the category of “surprise”. “Surprise” principle of war means, as the name suggest, a sudden attack. This means that this incident was done at a time or place or in a manner at which the other party/target is unprepared. -

Evaluation and Treatment of Blast Injuries

9/4/2014 Blast Injuries Objectives • An Overview of the Effects of Blast Injuries at the • Describe the basic physics, mechanisms of injury, and Medical Level pathophysiology of blast injury • List the four types or categories of blast injuries • List the factors associated with increased risk of Presented by: Jay Wuerker, EMT-P primary blast injury EMS Instructor II Objectives…cont. Why? • Recognize the key diagnostic indicators of serious • Combat primary blast injury • Terrorism • State the most common cause of death following an • Accidents explosion Combat: Iraq & Afghanistan Terrorism: USS Cole 1 9/4/2014 Terrorism: ??? Terrorism • Bombings are clearly the most common cause of casualties in terrorist incidents. • Recent terrorism has shown increasing numbers of suicidal bombers wearing or driving the explosive device • A poor man’s guided missile! Boston Marathon April 15, 2013 Pressure cooker device • Pressure cooker device (2), form of an IED • “Inspire” magazine Summer 2010, “Make a Bomb in • Same type of device used in Mumbai train bombings the Kitchen of your Mom”, by “The AQ chef”. in 2006 and Time Square car bomb attempt in 2010 • Al-Qaeda publication article on the step by step • Often packed with nails, ball bearings and other small process for making a Pressure cooker bomb. metal objects Boston Marathon Results • Three killed, 264 wounded – many with amputations, scene described as a war zone • One Police officer killed in shoot out with bomber suspect Dzhokhar Tsarnaev 2 9/4/2014 Not in Wisconsin? • Steve Preisler - aka “Uncle Fester” , from Green Bay , graduated from Marquette University in 1981 with a degree in Chemistry and Biology. -

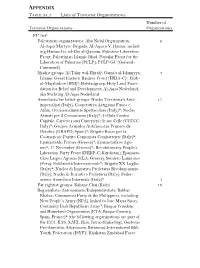

Lists of Terrorist Organizations

114 Consequences of Counterterrorism APPENDIX TABLE 3A.1 Lists of Terrorist Organizations Number of Terrorist Organizations Organizations EU lista Palestinian organizations: Abu Nidal Organization; 6 Al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigade; Al-Aqsa e.V. Hamas, includ- ing Hamas-Izz ad-Din al-Qassam; Palestine Liberation Front; Palestinian Islamic Jihad; Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP); PFLP-GC (General- Command) Jihadist groups: Al-Takir wal-Hijrahb; Gama’a al-Islamiyya; 7 Islamic Great Eastern Raiders Front (IBDA-C)c; Hizb- ul-Mujahideen (HM)d; Hofstadgroep; Holy Land Foun- dation for Relief and Development; Al-Aqsa Nederland, aka Stichting Al-Aqsa Nederland Anarchists/far leftist groups: Nuclei Territoriali Anti- 17 imperialisti (Italy); Cooperativa Artigiana Fuoco e Affini, Occasionalmente Spettacolare (Italy)*; Nuclei Armati per il Comunismo (Italy)*; Cellula Contro Capitale, Carcere i suci Carcerieri e le sue Celle (CCCCC: Italy)*; Grupos Armados Antifascistas Primero de Octubre (GRAPO; Spain)*; Brigate Rosse per la Costruzione Partito Comunista Combattente (Italy)*; Epanastatiki Pirines (Greece)*; Epanastatikos Ago- nas*; 17 November (Greece)*; Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party Front (DHKP-C; Kurdistan); Epanasta- tikos Laigos Agonas (ELA; Greece); Sendero Luminoso (Peru); Solidarietà Internazionale*; Brigata XX Luglio (Italy)*; Nucleo di Iniziativa Proletaria Rivoluzionaria (Italy); Nuclei di Iniziativa Proletaria (Italy); Feder- azione Anarchica Informale (Italy)* 1 Far rightist groups: Kahane Chai (Kach) 18 Regionalists/Autonomists/Independentists: -

1 United States District Court for the District Of

1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS ) UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) Criminal Action v. ) No. 13-10200-GAO ) DZHOKHAR A. TSARNAEV, also ) known as Jahar Tsarni, ) ) Defendant. ) ) BEFORE THE HONORABLE GEORGE A. O'TOOLE, JR. UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE EXCERPT JURY TRIAL - DAY TWENTY-SEVEN OPENING STATEMENT BY MR. WEINREB John J. Moakley United States Courthouse Courtroom No. 9 One Courthouse Way Boston, Massachusetts 02210 Wednesday, March 4, 2015 9:50 a.m. Marcia G. Patrisso, RMR, CRR Official Court Reporter John J. Moakley U.S. Courthouse One Courthouse Way, Room 3510 Boston, Massachusetts 02210 (617) 737-8728 Mechanical Steno - Computer-Aided Transcript 2 1 APPEARANCES: 2 OFFICE OF THE UNITED STATES ATTORNEY By: William D. Weinreb, Aloke Chakravarty and 3 Nadine Pellegrini, Assistant U.S. Attorneys John Joseph Moakley Federal Courthouse 4 Suite 9200 Boston, Massachusetts 02210 5 - and - UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE 6 By: Steven D. Mellin, Assistant U.S. Attorney Capital Case Section 7 1331 F Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20530 8 On Behalf of the Government 9 FEDERAL PUBLIC DEFENDER OFFICE By: Miriam Conrad, William W. Fick and Timothy G. Watkins, 10 Federal Public Defenders 51 Sleeper Street 11 Fifth Floor Boston, Massachusetts 02210 12 - and - CLARKE & RICE, APC 13 By: Judy Clarke, Esq. 1010 Second Avenue 14 Suite 1800 San Diego, California 92101 15 - and - LAW OFFICE OF DAVID I. BRUCK 16 By: David I. Bruck, Esq. 220 Sydney Lewis Hall 17 Lexington, Virginia 24450 On Behalf of the Defendant 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 3 1 P R O C E E D I N G S 2 * * * 3 MR. -

Pressure Cooker Bomb - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Pressure cooker bomb - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pressure_cooker_bomb From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia A pressure cooker bomb is a home-made bomb made by placing explosive material Pressure cooker bomb into a pressure cooker and attaching a blasting cap at the top of the cooker.[1] This type of bomb is a popular terrorist weapon. Al-Qaeda have published instructions for making pressure cooker bombs in an online jihadi magazine to encourage "lone wolf" attacks on enemies [2] of jihad. Pressure cooker fragment believed by the FBI to be part of Pressure cooker bombs have been used in a number of attacks in the 21st century. one of the explosive devices used Among them have been the 2006 Mumbai in the 2013 Boston Marathon train bombings, 2010 Stockholm bombings bombings (failed to explode), the 2010 Times Square car bombing attempt (failed to explode), and the 2013 Boston Marathon bombings.[3] 1 Description 2 History 2.1 2000–09 2.2 2010–present 3 See also 4 References 5 External links Pressure cooker bomb - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pressure_cooker_bomb Pressure cooker bombs are relatively easy to make since - apart from the explosive itself - only readily available materials are needed. The bomb can be ignited using a simple electronic device such as a digital watch, garage door opener, cell phone, pager, kitchen timer, or alarm clock.[1][4] The power of the explosion depends on the size of the pressure cooker and the amount and type of explosives used.[5] Pressure -

Lepsky Complaint

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Magistrate. No. 17-8071 (LOW) V. GREGORY LEPSJ(Y CRIMINAL COMPLAINT I, Tara Jerussi, being duly sworn, state the following is true and correct to the best of my knowledge and belief: SEE ATTACHMENT A I further state that I am a Special Agent with the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and that this complaint is based on the following facts: SEE ATTACHMENT B continued on the attached pages and made ~ rt ere) --lc--¥-=t----<i::'---- --- Tara ·uss1, ial Agent Federal Bureau of Investigation Sworn to by telephone pursuant to Fed. R. Crim. P. 4. l(b)(2)(A) May 4, 2017 at Newark, New Jersey Date Honorable Leda Dunn Wettre United States Magistrate Judge ·' .(Jl.t;r.\d e Lc:.t"~)I\"' We-~r e Name & Title ofJudicial Officer Signature of Judicial Officer ATTACHMENT A (Attempt to Provide Material Support to a Designated Foreign Terrorist Organization) From at least on or about December 24, 2016 until February 21, 2017, in Ocean County, in the District of New Jersey, and elsewhere, defendant GREGORY LEPSKY knowingly and unlawfully attempted to provide material support and resources, as defined in Title 18, United States Code, Section 2339A(b), including services and personnel, to a foreign terrorist organization, namely the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham, knowing that the organization was a designated terrorist organization, and that the organization had engaged and was engaging in terrorist activity and terrorism. In violation of Title 18, United States Code, Section 2339B(a)(l) and 2339B(d). -

SIGINT for Anyone

THE ORIGINS OF AMERICA’S JIHADISTS THE ORIGINS OF AMERICA’S About This Perspective The U.S. homeland faces a multilayered threat from terrorist organizations. Homegrown jihadists account for most of the terrorist activity in the United States since 9/11. Efforts by jihadist terrorist organizations to inspire terrorist attacks in the United States have thus far yielded meager results. No American jihadist group has emerged to sustain a terrorist campaign, and there is no evidence of an active jihadist underground to support a continuing terrorist holy war. The United States has invested significant resources in THE ORIGINS OF preventing terrorist attacks, and authorities have been able to uncover and thwart most of the terrorist plots. This Perspective identifies 86 plots to carry out terrorist attacks and 22 actual attacks since 9/11 involving 178 planners and perpetrators. Eighty-seven percent of those planners and perpetrators had long residencies in the United States. Only four of them had come to the United States illegally, all as minors. Nationality is a poor predictor of later terrorist activity, and vetting people coming to the United States, no matter how rigorous, cannot identify those who radicalize here. Determining whether a young teenager might, more than 12 years later, turn out to be a jihadist AMERICA’S terrorist would require the bureaucratic equivalent of divine foresight. Jenkins JIHADISTS Brian Michael Jenkins $21.00 ISBN-10 0-8330-9949-3 ISBN-13 978-0-8330-9949-5 52100 C O R P O R A T I O N www.rand.org Perspective EXPERT INSIGHTS ON A TIMELY POLICY ISSUE C O R P O R A T I O N 9 780833 099495 R PE-251-RC (2017) barcode_template_CC15.indd 1 10/17/17 12:00 PM Contents Summary of Key Judgments ..................................................................................1 The Origins of America’s Jihadists .........................................................................3 Appendix ............................................................................................................. -

After Action Report for the Response to the 2013 Boston Marathon Bombings

Afer Action Report for the Response to the 2013 Boston Marathon Bombings December 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ...............................................................................................................3 Project Management Team ...............................................................................................12 Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................13 Introduction ...........................................................................................................................15 Section 1: Incident Timeline ............................................................................................18 Section 2: Overview of Incidents ....................................................................................34 Marathon Monday 2013 .......................................................................................................35 Ongoing Activities ................................................................................................................47 Apprehension of Suspects ....................................................................................................53 Recovery .................................................................................................................................66 Section 3: Analysis of Capabilities .................................................................................70 Focus Area 1: Preparedness ...............................................................................................71 -

The “Jihadi Wolf” Threat

The Hague, 11/04/2017 THE “JIHADI WOLF” THREAT THE EVOLUTION OF TERROR NARRATIVES BETWEEN THE (CYBER-)SOCIAL ECOSYSTEM AND SELF-RADICALIZATION “EGO-SYSTEM” This paper was presented at the 1st European Counter Terrorism Centre (ECTC) conference on online terrorist propaganda, 10-11 April 2017, at Europol Headquarters, The Hague. The views expressed are the authors’ own and do not necessarily represent those of Europol. Author: Arije Antinori, PhD EUROPOL PUBLIC INFORMATION 1 / 11 Europol Public Information 1 Introduction In this paper, the JIHAD concept has to be understood not as the original spiritual meaning in Islam, but the violent-based ideological distortion of terrorism as re- ported in Open Source Jihad (OSJ), a key-section of the digital magazine ‘Inspire’, published by al_Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) as of 2010, and to date at its 16th issue. The use of the term ‘(cyber-)’ - in brackets - aims to highlight the already blurred boundary between ‘real’ and ‘cyber’ (as not real) dimension of life. Nowadays, the ‘cyber’ dimension can no longer be considered ‘other’ in comparison with the uniqueness of the human experience, especially within social dynamics. This blur- ring is totally redefining the concept of criminality. This imposes the introduction of new semantic, new methodological and technical approaches to monitor, analyse, prevent, anticipate and counter the evolving terrorist threat. Considering the aniconism and iconoclasm in Islam, the evolution of ‘Internet Ji- hadism’[1]points out the complete revolution represented by the born of a specific (cyber-)visual-storytelling. The violent videos, infographics and images reinforce the cultural impact of the pseudo-religious messages.