UK-US Trade Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservative Party Leaders and Officials Since 1975

BRIEFING PAPER Number 07154, 6 February 2020 Conservative Party and Compiled by officials since 1975 Sarah Dobson This List notes Conservative Party leaders and officials since 1975. Further reading Conservative Party website Conservative Party structure and organisation [pdf] Constitution of the Conservative Party: includes leadership election rules and procedures for selecting candidates. Oliver Letwin, Hearts and Minds: The Battle for the Conservative Party from Thatcher to the Present, Biteback, 2017 Tim Bale, The Conservative Party: From Thatcher to Cameron, Polity Press, 2016 Robert Blake, The Conservative Party from Peel to Major, Faber & Faber, 2011 Leadership elections The Commons Library briefing Leadership Elections: Conservative Party, 11 July 2016, looks at the current and previous rules for the election of the leader of the Conservative Party. Current state of the parties The current composition of the House of Commons and links to the websites of all the parties represented in the Commons can be found on the Parliament website: current state of the parties. www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Conservative Party leaders and officials since 1975 Leader start end Margaret Thatcher Feb 1975 Nov 1990 John Major Nov 1990 Jun 1997 William Hague Jun 1997 Sep 2001 Iain Duncan Smith Sep 2001 Nov 2003 Michael Howard Nov 2003 Dec 2005 David Cameron Dec 2005 Jul 2016 Theresa May Jul 2016 Jun 2019 Boris Johnson Jul 2019 present Deputy Leader # start end William Whitelaw Feb 1975 Aug 1991 Peter Lilley Jun 1998 Jun 1999 Michael Ancram Sep 2001 Dec 2005 George Osborne * Dec 2005 July 2016 William Hague * Dec 2009 May 2015 # There has not always been a deputy leader and it is often an official title of a senior Conservative politician. -

Business West Infographic Full

Business West Many Faces. Many Successes. What would you like to see? Story Support Voice of Business West for business of business OUR AIM To make this the best place to: Live Learn Work Prosper WHO WE ARE We work with 20,000 businesses All sectors LARGE and all sizes MEDIUM SMALL 95% of corporates in our region are members OUR COMPANY A not-for-dividend We are Owned and governed by company non-political business community 225 £13m sta turnover We’re the largest Chamber of Commerce in the UK and established 1823 We’re award winning Enterprising Best Business Development Britain Award and Job Creation Project for Export 2017 Best job creation ICC project Best International Project European Sunday Times Enterprise Top 100 2018, Promotion 2017 & 2016 Awards Finalist OUR REACH In 2017 our media comments reached 10,000 followers 16.1m on LinkedIn 18,000 followers on Twitter What else would you like to see? Support Voice for business of business OVER THE PAST TWO YEARS WE HELPED create 4,400 JOBS 1,400 £650m 85,000 helped start-up, export sales from export documents scale-up and 700 exporters processed innovate WE DELIVER CONTRACTS FOR WE WORK WITH ‘Business West is hands down the best business support organisation I've worked with in the UK, delivering results where other regional services simply haven't.’ Robert Sugar, MD at Urban Hawk & Crocotta What else would you like to see? Story Voice of Business West of business OUR TRACK RECORD The driving force behind: Redevelopment of Creation of Cabot Supporting City Harbour Circus Gloucestershire 2050 Evolution of Switch Reducing train journey Influencing skills and on to Swindon times to London training in the region We created successful spin o organisations: OUR INFLUENCE For 200 years we’ve worked with diverse partners to create a region rich in culture, with equality and opportunity for all. -

Politeia Let Freedom Prevail

Let Freedom Prevail! Liam Fox POLITEIA 2005 First published in 2005 by Politeia 22 Charing Cross Road London, WC2H 0QP Tel: 020 7240 5070 Fax: 020 7240 5095 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.politeia.co.uk © Politeia 2005 Address Series No. 16 ISBN 1 900 525 87 9 Cover design by John Marenbon Printed in Great Britain by Sumfield & Day Ltd 2 Park View, Alder Close, Eastbourne BN23 6QE www.sumfieldandday.com THE AUTHOR Dr Liam Fox has been the Member of Parliament for Woodspring since April 1992 and in the last Conservative Government he was Parliamentary Under-Secretary at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office from 1996 until the 1997 election. Since 1997 he has been a member of the Shadow Cabinet and served as Opposition Front Bench Spokesman on Constitutional Affairs and Shadow Secretary of State for Health. In the last Parliament he was Co- Chairman of the Conservative Party and is now Shadow Foreign Secretary. Amongst his Politeia publications are Holding Our Judges to Account (September 1999) and Conservatism for the Future (March 2004). Liam Fox As the country looks ahead to the new Parliament, the lessons of the past – and the general election – will, with time and objective analysis, become clear. But one point is evident: no opposition can easily fight an election against the backdrop of an economy perceived – rightly or wrongly – to be in a benevolent state. The Conservative party should therefore avoid an instant judgement, and one lacking the perspective of time, as it prepares for the next Parliament and the future. -

Race and Elections

Runnymede Perspectives Race and Elections Edited by Omar Khan and Kjartan Sveinsson Runnymede: Disclaimer This publication is part of the Runnymede Perspectives Intelligence for a series, the aim of which is to foment free and exploratory thinking on race, ethnicity and equality. The facts presented Multi-ethnic Britain and views expressed in this publication are, however, those of the individual authors and not necessariliy those of the Runnymede Trust. Runnymede is the UK’s leading independent thinktank on race equality ISBN: 978-1-909546-08-0 and race relations. Through high-quality research and thought leadership, we: Published by Runnymede in April 2015, this document is copyright © Runnymede 2015. Some rights reserved. • Identify barriers to race equality and good race Open access. Some rights reserved. relations; The Runnymede Trust wants to encourage the circulation of • Provide evidence to its work as widely as possible while retaining the copyright. support action for social The trust has an open access policy which enables anyone change; to access its content online without charge. Anyone can • Influence policy at all download, save, perform or distribute this work in any levels. format, including translation, without written permission. This is subject to the terms of the Creative Commons Licence Deed: Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 UK: England & Wales. Its main conditions are: • You are free to copy, distribute, display and perform the work; • You must give the original author credit; • You may not use this work for commercial purposes; • You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. You are welcome to ask Runnymede for permission to use this work for purposes other than those covered by the licence. -

The EU Referendum - the Two Sides Line up Cheat Sheet by Dave Child (Davechild) Via Cheatography.Com/1/Cs/415

The EU Referendum - The Two Sides Line Up Cheat Sheet by Dave Child (DaveChild) via cheatography.com/1/cs/415/ Campaign Support - Political Parties REMAIN CAMPAIGN LEAVE CAMPAIGN Conserv ative Party British National Party (BNP) Labour Party Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) Liberal Democrats UK Indepen dence Party (UKIP) Green Party of England and Wales Green Party in Northern Ireland Plaid Cymru Scottish National Party (SNP) Scottish Green Party Sinn Fein Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) All parties have individ uals voting against the party line. You can find these listed in detail at https:/ /en .wi kip edi a.or g/ wik i/E ndo rse men ts_ in_ th‐ e_Un ite d_K ing dom _Eu rop ean _Un ion _me mbe rsh ip_ ref ere ndu m,_ 2016 Campaign Support - Organis ations REMAIN CAMPAIGN LEAVE CAMPAIGN Inter nat ional Organis ati ons European Central Bank None G7 G20 World Trade Organiz ation (WTO) World Bank Interna tional Monetary Fund (IMF) North Atlantic Treaty Organis ation (NATO) Trade Unions Trades Union Congress (TUC) Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen Broadca sting, Enterta inm ent, Cinemat ograph and Theatre Union Bakers, Food and Allied Workers' Union Communi cation Workers Union National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers (RMT) Equity Indian Workers' Associa tion Community Fire Brigades Union GMB Musicians' Union Royal College of Midwives Transport Salaried Staffs' Associa tion By Dave Child (DaveChild) Not published yet. Sponsored by Readable.com cheatography.com/davechild/ Last updated 14th June, 2016. Measure your website readability! aloneonahill.com Page 1 of 3. -

The Political Economy of Brexit and the UK's National Business Model

SPERI Paper No. 41 The Political Economy of Brexit and the UK’s National Business Model. Edited by Scott Lavery, Lucia Quaglia and Charlie Dannreuther About SPERI The Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute (SPERI) at the University of Sheffield brings together leading international researchers, policy-makers, journalists and opinion formers to develop new ways of thinking about the economic and political challenges by the current combination of financial crisis, shifting economic power and environmental threat. SPERI’s goal is to shape and lead the debate on how to build a sustainable recovery and a sustainable political economy for the long-term. ISSN 2052-000X Published in May 2017 SPERI Paper No. 41 – The Political Economy of Brexit and the UK’s National Business Model 1 Content Author details 2 Introduction 4 Scott Lavery, Lucia Quaglia and Charlie Dannreuther The political economy of finance in the UK and Brexit 6 Scott James and Lucia Quaglia Taking back control? The discursive constraints on post-Brexit 11 trade policy Gabriel Siles-Brügge Paying Our Way in the World? Visible and Invisible Dangers of 17 Brexit Jonathan Perraton Brexit Aesthetic and the politics of infrastructure investment 24 Charlie Dannreuther What’s left for ‘Social Europe’? Regulating transnational la- 33 bour markets in the UK-1 and the EU-27 after Brexit Nicole Lindstrom Will Brexit deepen the UK’s ‘North-South’ divide? 40 Scott Lavery Putting the EU’s crises into perspective 46 Ben Rosamond SPERI Paper No. 41 – The Political Economy of Brexit and the UK’s National Business Model 2 Authors Scott Lavery is a Research Fellow at the Sheffield Political Economy Research In- stitute (SPERI) at the University of Sheffield. -

2014 Cabinet Reshuffle

2014 Cabinet Reshuffle Overview A War Cabinet? Speculation and rumours have been rife over Liberal Democrat frontbench team at the the previous few months with talk that the present time. The question remains if the Prime Minister may undertake a wide scale Prime Minister wishes to use his new look Conservative reshuffle in the lead up to the Cabinet to promote the Government’s record General Election. Today that speculation was in this past Parliament and use the new talent confirmed. as frontline campaigners in the next few months. Surprisingly this reshuffle was far more extensive than many would have guessed with "This is very much a reshuffle based on the Michael Gove MP becoming Chief Whip and upcoming election. Out with the old, in William Hague MP standing down as Foreign with the new; an attempt to emphasise Secretary to become Leader of the House of diversity and put a few more Eurosceptic Commons. Women have also been promoted faces to the fore.” to the new Cameron Cabinet, although not to the extent that the media suggested. Liz Truss Dr Matthew Ashton, politics lecturer- MP and Nicky Morgan MP have both been Nottingham Trent University promoted to Secretary of State for Environment and Education respectively, whilst Esther McVey MP will now attend Europe Cabinet in her current role as Minister for Employment. Many other women have been Surprisingly Lord Hill, Leader for the promoted to junior ministry roles including Conservatives in the House of Lords, has been Priti Patel MP to the Treasury, Amber Rudd chosen as the Prime Minister’s nomination for MP to DECC and Claire Perry MP to European Commissioner in the new Junker led Transport, amongst others. -

Michael Kenny and Nick Pearce, Shadows of Empire. the Anglosphere in British Politics (Cambridge, Polity Press, 2018), Pp

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SPIRE - Sciences Po Institutional REpository Michael Kenny and Nick Pearce, Shadows of Empire. The Anglosphere in British Politics (Cambridge, Polity Press, 2018), pp. 224 ISBN 978-1-5095-1661-2 Reviewed by Christian Lequesne Sciences Po-CERI, Paris The idea of an alliance between the UK and the old Commonwealth colonies has made a comeback in the context of Brexit. Some media have reported that one of the prominent partisans of Brexit in Theresa May’s Cabinet, Liam Fox, referred to Brexit as ‘Empire 2.0’ in a meeting of Commonwealth ministers. Has Brexit created in the UK the opportunity for the resurrection of forms of national nostalgia which have been present but marginal in British politics since the 1950s? Kenny and Pearce trace the historical origins and legacy of what they call the idea of Anglosphere in British politics. They do it in a very concise and detailed way, which makes this book useful to scholars, students, but also to every reader who wants to reflect not only on the short term but also long term effects of British history on Brexit. The book is built around seven chronological chapters with started in the 19th century to finish in the very contemporary period. For the two authors, the idea of Anglosphere found its roots in the Victorian period. It has then been present inside the Conservative Party with more or less relevance according to the periods. For instance, notions of the Anglosphere were reactivated by Winston Churchill during the Second World War, although Kenny and Pearce insist that scholars must be cautious when they analyse Churchill’s conception of the Anglosphere. -

A Guide to the Government for BIA Members

A guide to the Government for BIA members Correct as of 29 November 2018 This is a briefing for BIA members on the Government and key ministerial appointments for our sector. It has been updated to reflect the changes in the Cabinet following the resignations in the aftermath of the government’s proposed Brexit deal. The Conservative government does not have a parliamentary majority of MPs but has a confidence and supply deal with the Northern Irish Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). The DUP will support the government in key votes, such as on the Queen's Speech and Budgets. This gives the government a working majority of 13. Contents: Ministerial and policy maker positions in the new Government relevant to the life sciences sector .......................................................................................... 2 Ministerial brief for the Life Sciences.............................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Theresa May’s team in Number 10 ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 7 Ministerial and policy maker positions in the new Government relevant to the life sciences sector* *Please note that this guide only covers ministers and responsibilities pertinent to the life sciences and will be updated as further roles and responsibilities are announced. -

Economy and Industrial Strategy Committee Membership Prime

Economy and Industrial Strategy Committee Membership Prime Minister, First Lord of the Treasury and Minister for (The Rt Hon Theresa May MP) the Civil Service (Chair) Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and Minister for the (The Rt Hon David Lidington MP) Cabinet Office (Deputy Chair) Chancellor of the Exchequer (The Rt Hon Philip Hammond MP) Secretary of State for Defence (The Rt Hon Gavin Williamson MP) Secretary of State for Education (The Rt Hon Damian Hinds MP) Secretary of State for International Trade (The Rt Hon Liam Fox MP) Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (The Rt Hon Greg Clark MP) Secretary of State for Health and Social Care (The Rt Hon Jeremy Hunt MP) Secretary of State for Work and Pensions (The Rt Hon Esther McVey MP) Secretary of State for Transport (The Rt Hon Chris Grayling MP) Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local (The Rt Hon Sajid Javid MP) Government Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (The Rt Hon Michael Gove MP) Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (The Rt Hon Matt Hancock MP) Minister without Portfolio (The Rt Hon Brandon Lewis MP) Minister of State for Immigration (The Rt Hon Caroline Nokes MP) Minister of State for Trade and Export Promotion (Baroness Rona Fairhead) Terms of Reference To consider issues relating to the economy and industrial strategy. Economy and Industrial Strategy (Airports) sub-Committee Membership Prime Minister, First Lord of the Treasury and Minister for the (The Rt Hon Theresa May MP) Civil Service -

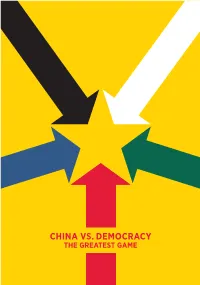

China Vs. Democracy the Greatest Game

CHINA VS. DEMOCRACY THE GREATEST GAME A HANDBOOK FOR DEMOCRACIES By Robin Shepherd, HFX Vice President ABOUT HFX HFX convenes the annual Halifax International Security Forum, the world’s preeminent gathering for leaders committed to strengthening strategic cooperation among democracies. The flagship meeting in Halifax, Nova Scotia brings together select leaders in politics, business, militaries, the media, and civil society. HFX published this handbook for democracies in November 2020 to advance its global mission. halifaxtheforum.org CHINA VS. DEMOCRACY: THE GREATEST GAME ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, HFX acknowledges Many experts from around the world the more than 250 experts it interviewed took the time to review drafts of this from around the world who helped to handbook. Steve Tsang, Director of the reappraise China and the challenge it China Institute at the School of Oriental poses to the world’s democracies. Their and African Studies (SOAS) in London, willingness to share their expertise and made several important suggestions varied opinions was invaluable. Of course, to early versions of chapters one and they bear no responsibility, individually or two. Peter Hefele, Head of Department collectively, for this handbook’s contents, Asia and Pacific, and David Merkle, Desk which are entirely the work of HFX. O!cer China, at Germany’s Konrad- Adenauer-Stiftung made a number of This project began as a series of meetings very helpful suggestions. Ambassador hosted by Baroness Neville-Jones at the Hemant Singh, Director General of the U.K. House of Lords in London in 2019. Delhi Policy Group (DPG), and Brigadier At one of those meetings, Baroness Arun Sahgal (retired), DPG Senior Fellow Neville-Jones, who has been a stalwart for Strategic and Regional Security, friend and supporter since HFX began in provided vital perspective from India. -

Sun Results 110711 Politicians Recognition and Approval

YouGov / The Sun Survey Results Sample Size: 2571 GB Adults Fieldwork: 10th - 11th July 2011 Voting intention 2010 Vote Gender Age Social grade Region Lib Lib Rest of Midlands / Total Con Lab Con Lab Male Female 18-24 25-39 40-59 60+ ABC1 C2DE London North Scotland Dem Dem South Wales Weighted Sample 2571 692 850 207 771 703 565 1250 1321 311 656 879 725 1465 1106 329 836 550 632 224 Unweighted Sample 2571 682 814 207 764 670 568 1218 1353 209 689 956 717 1679 892 420 818 520 576 237 % %%%%%% % % % % % % % % % % % % % [A random selection of half of respondents were shown images of the following politicians] Who is this person? Image shown of IDS [Split 1 n=1265] William Hague 3 222313 2 3 1 2 3 3 3 2 4 2 0 4 3 David Cameron 0 000000 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 George Osborne 1 100110 0 1 0 0 2 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 Michael Gove 0 000000 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Andrew Lansley 0 000000 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 Ken Clarke 0 001010 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 Liam Fox 0 000000 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Danny Alexander 0 000000 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Chris Huhne 0 100000 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 Nick Clegg 0 000000 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 Vince Cable 1 113122 0 2 1 1 1 2 2 1 3 2 1 1 0 Ed Miliband 0 000000 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 Ed Balls 0 000000 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 David Miliband 0 000000 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Douglas Alexander 0 000000 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Eric Pickles 0 000000 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Philip Hammond 0 000000 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Jeremy Hunt 0 010010 0 0 3 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 Hilary Benn 0 000000 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Andy Burnham 0 010000 1 0 2 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 Alan Johnson 0 000000 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 Iain Duncan Smith 69 79 72 70 77 73 68 78 60 47 65 71 79 72 64 69 68 69 69 67 Not sure 24 15 21 25 17 21 26 17 31 43 29 22 15 21 30 22 24 26 24 25 1 © 2011 YouGov plc.