Michael C Bonello: Malta's Economy on the Path to the Euro

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2007

4 THE CASH CHANGEOVER IN CYPRUS AND MALTA Six years after the successful introduction of the Monnaie de Paris minted 200.0 million euro coins euro banknotes and coins in 12 euro area countries with a face value of €56.1 million for Malta. at the same time and one year after Slovenia joined the Eurosystem, the euro banknotes and The Central Bank of Cyprus began frontloading coins were successfully introduced in Cyprus and euro coins to credit institutions on 22 October 2007; Malta on 1 January 2008. After a dual circulation the frontloading of euro banknotes began on period of one month, the euro had fully replaced 19 November 2007. Sub-frontloading to retailers the Cyprus pound and the Maltese lira. and the cash-operated machine industry started at the same time as the frontloading operation. As in the previous cash changeovers, timely and A widespread predistribution of euro coins was comprehensive preparation was crucial to the supported by making some 40,000 pre-packed smooth introduction of the euro banknotes and coin starter kits, worth €172 each, available to coins. Both Cyprus and Malta had established businesses and retailers from 3 December 2007. changeover plans at the national level long 250,000 mini-kits, worth CYP 10 each, went on before €-Day. These plans were based on, among sale to the general public on the same date. other things, the legal framework adopted by the Governing Council in July 2006 in relation to In Malta the frontloading of euro coins started certain preparations for the euro cash changeover in late September 2007, while the frontloading and the frontloading and sub-frontloading of euro of euro banknotes began in late October. -

The Maltese Lira

THE MALTESE LIRA On 16 May 1972, the Central Bank of Malta issued the first series of decimal coinage based on the Maltese Lira, at the time being roughly equivalent to the British Pound. Each Lira was divided in 100 cents (abbreviation of centesimo, meaning 1/100), while each cent was subdivided in 10 mills (abbreviation of millesimo, meaning 1/1000). The mills coins of the 1972 series - withdrawn from circulation in 1994 9 COINS AND 3 BANKNOTES Initially, a total of 8 coins were issued, namely the 50 cent, 10 cent, 5 cent, 2 cent, 1 cent, 5 mill, 3 mill and 2 mill. These coins were complemented by the issue of three banknotes, namely the 1 Lira, 5 Lira and 10 Lira, on 15 January 1973. Furthermore, a 25 cent coin was introduced in June 1975 to commemorate Malta becoming a Republic within the Commonwealth of Nation on 13 December 1974. This was the first coin to feature the coat of arms of the Republic of Malta on the reverse. NEW SERIES The obverse of the 1986/1991 series - withdrawn from circulation in January 2008 A new series was issued on 19 May 1986. This comprised 7 coins, namely the 1 Lira, 50 cent, 25 cent, 10 cent, 5 cent, 2 cent and 1 cent. Each coin depicted local fauna and flora on the The banknotes of the 1989 series - withdrawn from circulation in January 2008 obverse and the emblem of the Republic on the reverse. No mills were struck as part of this series, though the 5 mil, 3 mil and 2 mil coins issued in 1972 continued to have legal tender. -

1 TREASURY REPORTING RATES of EXCHANGE As of December 31, 2009 Foreign Currency Country-Currency to $1.00

04/29/15 Page: 1 TREASURY REPORTING RATES OF EXCHANGE As of December 31, 2009 Foreign Currency Country-Currency To $1.00 Afghanistan-Afghani 47.9200 Albania-Lek 95.4300 Algeria-Dinar 70.3330 Angola-Kwanza 75.0000 Antigua & Barbuda-E. Caribbean Dollar 2.7000 Argentina-Peso 3.7980 Armenia-RUBLE 375.0000 Australia-Dollar 1.1110 Austria-Euro .6950 Austria-Schilling .0000 Azerbaidjan-Ruble .8200 Azerbaijan-New Manat .0000 Bahamas-Dollar 1.0000 Bahrain-Dinar .3770 Bangladesh-Conv. Taka .0000 Bangladesh-Non-Conv. Taka 68.0000 Barbados-Dollar 2.0200 Belarus-Ruble 2,880.0000 Belgium-Euro .6950 Belgium-Franc .0000 Belize-Dollar 2.0000 Benin-CFA Franc 454.8900 Bermuda-Dollar 1.0000 Bolivia-Boliviano 6.9700 Bosnia-Dinar 1.3590 Botswana-Pula 6.6530 Brazil-Cruzados .0000 Brazil-Cruzeiro 1.7400 Brunei-Dollar 1.4010 Bulgaria-Lev 1.3580 Burkina Faso-CFA Franc 454.8900 Burma-Kyat 450.0000 Burundi-Franc 1,200.0000 Cambodia (Khmer)-Riel 4,163.0000 Cameroon-CFA Franc 454.8900 Canada-Dollar 1.0510 Cape Verde-Escudo 74.7270 Cayman Island-Dollar .0000 Central African Rep.-CFA Franc 454.8900 Chad-CFA Franc 454.8900 Chile-Peso 507.0000 China-Renminbi 6.8260 China-Yuan .0000 Colombia-Peso 2,046.5000 Comoros-CFA Franc 361.3500 Congo-CFA Franc 454.8900 Costa Rica-Colon 553.7000 Croatia-KUNA 5.0000 Cuba-Peso .9260 Cyprus-Euro .0000 Cyprus-Pound .0000 Czech. Republic-Koruna 18.1190 Czechoslovakia-Tuzex Koruna .0000 CFA Franc-CFA Franc .0000 Dem. Rep. of Congo-Congolese Franc 900.0000 Denmark-Kroner 5.1670 Djibouti-Franc 177.0000 Dominican Republic-Peso 36.1000 East Germany-GDR Mark .0000 Ecuador-Dollar 1.0000 Ecuador-Sucre .0000 Egypt-Pound 5.4840 El Salvador-Colon 1.0000 Equatorial Guinea-CFA Franc 454.8900 Eritrea-Birr 15.0000 Estonia-EURO .0000 Estonia-Kroon 10.8650 04/29/15 Page: 2 TREASURY REPORTING RATES OF EXCHANGE As of December 31, 2009 Foreign Currency Country-Currency To $1.00 Ethiopia-Birr 12.6400 Euro-Euro .6950 European Community-European Comm. -

Malta Adopts the Euro

IP/08/2 Brussels, 1 January 2008 Malta adopts the euro Malta adopted the euro today. All available data indicate that the changeover from the Maltese lira went well and as planned. Citizens are able to withdraw euro cash from ATMs in Malta and to use it for daily payments. "Today is another proud day in Malta's proud history. A day in which it took its place at the heart of the European Union. The euro is a strong and stable currency. Along with the economic reforms the EU and Member States have undertaken, it is a reason why the European economy is still growing despite some difficult challenges caused by high energy and commodity prices. By joining the euro, Malta has said yes to stability, to reform and to hassle-free trade and travel for its businesses and citizens", said Commission President José-Manuel Barroso. "The adoption of the euro is a historic event for Malta less than four years after you became a member of the European Union. This achievement has become possible thanks to Malta's stability-oriented economic policies. Please stay on the right path! I want to congratulate the Maltese authorities and all who have contributed to what are very comprehensive practical preparations", said Joaquín Almunia, European Commissioner for Economic and Monetary Affairs. The euro is Malta's currency as of today. The euro has replaced the Maltese lira at a rate of MTL 0.429300 for one euro (or € 2.33 per lira), following a decision taken by the Ecofin Council in July on a Commission proposal. -

March 31, 2013 Foreign Currency Country-Currency to $1.00

04/29/15 Page: 1 TREASURY REPORTING RATES OF EXCHANGE As of March 31, 2013 Foreign Currency Country-Currency To $1.00 Afghanistan-Afghani 53.1800 Albania-Lek 109.0700 Algeria-Dinar 78.9000 Angola-Kwanza 95.0000 Antigua & Barbuda-E. Caribbean Dollar 2.7000 Argentina-Peso 5.1200 Armenia-RUBLE 415.0000 Australia-Dollar .9600 Austria-Euro .7800 Austria-Schilling .0000 Azerbaidjan-Ruble .8000 Azerbaijan-New Manat .0000 Bahamas-Dollar 1.0000 Bahrain-Dinar .3800 Bangladesh-Conv. Taka .0000 Bangladesh-Non-Conv. Taka 80.0000 Barbados-Dollar 2.0200 Belarus-Ruble 8,680.0000 Belgium-Euro .7800 Belgium-Franc .0000 Belize-Dollar 2.0000 Benin-CFA Franc 511.6700 Bermuda-Dollar 1.0000 Bolivia-Boliviano 6.9600 Bosnia-Dinar 1.5300 Botswana-Pula 8.2400 Brazil-Cruzados .0000 Brazil-Cruzeiro 2.0200 Brunei-Dollar 1.2400 Bulgaria-Lev 1.5300 Burkina Faso-CFA Franc 511.6700 Burma-Kyat 878.0000 Burundi-Franc 1,650.0000 Cambodia (Khmer)-Riel 4,103.0000 Cameroon-CFA Franc 511.6700 Canada-Dollar 1.0200 Cape Verde-Escudo 84.1800 Cayman Island-Dollar .8200 Central African Rep.-CFA Franc 511.6700 Chad-CFA Franc 511.6700 Chile-Peso 471.5000 China-Renminbi 6.2100 China-Yuan .0000 Colombia-Peso 1,824.0000 Comoros-CFA Franc 361.3500 Congo-CFA Franc 511.6700 Costa Rica-Colon 498.6000 Croatia-KUNA 5.8300 Cuba-Peso 1.0000 Cyprus-Euro .7800 Cyprus-Pound .7890 Czech. Republic-Koruna 19.7000 Czechoslovakia-Tuzex Koruna .0000 CFA Franc-CFA Franc .0000 Dem. Rep. of Congo-Congolese Franc 920.0000 Denmark-Kroner 5.8200 Djibouti-Franc 177.0000 Dominican Republic-Peso 40.8600 East Germany-GDR Mark .0000 Ecuador-Dollar 1.0000 Ecuador-Sucre .0000 Egypt-Pound 6.8000 El Salvador-Colon 1.0000 Equatorial Guinea-CFA Franc 511.6700 Eritrea-Birr 15.0000 Estonia-EURO .7800 Estonia-Kroon 11.6970 04/29/15 Page: 2 TREASURY REPORTING RATES OF EXCHANGE As of March 31, 2013 Foreign Currency Country-Currency To $1.00 Ethiopia-Birr 18.4000 Euro-Euro .7800 European Community-European Comm. -

List of Abbreviations and Acronyms Eurostat Yearbook

EurostatEurostat yearbookyearbook 20042004 List of abbreviations and acronyms D-W territory of the former West Germany Member States DZ Algeria GB Great Britain EU-25 the 25 Member States of the European Union HR Croatia EU-15 the 15 Member States of the European Union IN India until 30.4.2004 IQ Iraq euro zone EUR-11 (BE, DE, ES, FR, IE, IT, LU, NL, AT, PT, IR Iran FI) until 31.12.2000 IS Iceland EUR-12 from 1.1.2001 JP Japan EUR-12 The euro zone with KR South Korea 12 countries participating LI Liechtenstein (BE, DE, EL, ES, FR, IE, IT, LU, NL, AT, PT, FI) LK Sri Lanka BE Belgium LY Libya CZ Czech Republic NG Nigeria DK Denmark NO Norway DE Germany RU Russian Federation EE Estonia SA Saudi Arabia EL Greece SG Singapore ES Spain SL Sierra Leone FR France SO Somalia IE Ireland TW Taiwan IT Italy UA Ukraine CY Cyprus US United States of America LV Latvia ZA South Africa LT Lithuania LU Luxembourg HU Hungary Currencies MT Malta NL Netherlands ECU European currency unit, data up to AT Austria 31.12.1998 PL Poland EUR (1) euro, data from 1.1.1999 onwards PT Portugal ATS (1) Austrian schilling SI Slovenia BEF (1) Belgian franc SK Slovakia CYP Cyprus pound FI Finland CZK Czech koruna SE Sweden DEM (1) German mark UK United Kingdom DKK Danish crown (krone) EEK Estonian kroon 1 Candidate countries ESP ( ) Spanish peseta FIM (1) Finnish markka 1 BG Bulgaria FRF ( ) French franc RO Romania GBP pound sterling 1 TR Turkey GRD ( ) Greek drachma HUF forint IEP (1) Irish pound (punt) Other countries and territories ITL (1) Italian lira LTL litas AF Afghanistan LUF (1) Luxembourg franc AM Armenia LVL lats AR Argentina MTL Maltese lira AZ Azerbaijan NLG (1) Dutch guilder BA Bosnia and Herzegovina PLN zloty BR Brazil PTE (1) Portuguese escudo CA Canada SEK Swedish crown (krona) CD Democratic Republic of Congo SIT tolar CH Switzerland SKK Slovak koruna CN China BGN lev CO Colombia CS Serbia and Montenegro (1) The euro replaced the ecu (code = ECU) on 1 January 1999. -

Quarterly Review

Central Bank of Malta Quarterly Review March 2002 Vol. 35 No.1 The Quarterly Review is prepared and issued by the Economics Division of the Central Bank of Malta. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Bank. Articles appearing in this issue may be reprinted in whole or in part provided the source is quoted. For copies of the Quarterly Review apply to:- The Manager External Relations Office Central Bank of Malta Castille Place Valletta CMR 01 Malta Telephone: (356) 21 247 480 Facsimile: (356) 21 243 051 Internet: www.centralbankmalta.com e-mail: [email protected] ISSN 0008-9273 Printed by Interprint Limited CONTENTS ECONOMIC SURVEY 1. Foreword 5 2. The International Environment 7 3. The Domestic Economy 11 Box 1: Business Perceptions Survey 19 4. The Balance of Payments and the Maltese Lira 22 5. Government Finance 27 6. Monetary and Financial Developments 31 7. The Banking System 38 Box 2: International Banking Institutions 42 NEWS NOTES 45 FINANCIAL POLICY CALENDAR 47 STATISTICAL TABLES 59 Notes: The cut-off date for information published in the Economic Survey is April 23, 2002. For figures published in the Statistical Tables, the cut-off date is April 23, 2002. Figures in Tables may not add up due to rounding. ECONOMIC SURVEY subdued. This was confirmed by data published in 1. FOREWORD March, which showed that Gross Domestic Product contracted by 2.9% in real terms during the final quarter of 2001, as the export During the final quarter of 2001 the Central Bank performance of the electronics sector deteriorated continued to ease its monetary policy stance. -

Lessons from ERM for ERM II

EMU strategies: Lessons from Greece in view of EU enlargement by Theodoros Papaspyrou* Paper presented at the Hellenic Observatory, The European Institute, London School of Economics 20 January 2004 *Special Adviser, Bank of Greece, on leave from the European Commission, DG Economic and Financial Affairs. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily correspond to those of the above institutions. Contents Introduction 1. Early steps in European Monetary Integration The Werner Plan and the ‘Snake’ The European Monetary System 2. EMU: a regime change in Europe’s money 3. Lessons from convergence experiences 4. The ERM II as a framework for guiding convergence Box: ERM II: narrow or broad bands are relevant? 5. Capital mobility and ERM II: an adversary or an ally in the drive for euro membership? 6. Concluding remarks Annex 1: Key dates of European Monetary Integration Annex 2: Greece: Monetary policy strategy during 1995-2000 Annex 3: Greece: key dates in the convergence effort towards the euro Annex 4: Maastricht Treaty: Exchange Rate criterion Annex 5: Exchange rate regimes in Accession countries Graphs and Tables 2 EMU strategies: Lessons from Greece in view of EU enlargement1 Introduction This paper, after reviewing briefly the early steps of European monetary integration and key elements of the EMU project as reflected in the Treaty of Maastricht, analyses the monetary integration strategy and convergence experience of member states, notably that of Greece, in the 1990s which led to the adoption of the euro. From this analysis, a number of key lessons are drawn which may be useful to future candidates to euro membership -in view of the enlargement- in designing their economic and monetary convergence strategies. -

WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates

The WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates The WM/Refinitiv Closing Exchange Rates are available on Eikon via monitor pages or RICs. To access the index page, type WMRSPOT01 and <Return> For access to the RICs, please use the following generic codes :- USDxxxFIXz=WM Use M for mid rate or omit for bid / ask rates Use USD, EUR, GBP or CHF xxx can be any of the following currencies :- Albania Lek ALL Austrian Schilling ATS Belarus Ruble BYN Belgian Franc BEF Bosnia Herzegovina Mark BAM Bulgarian Lev BGN Croatian Kuna HRK Cyprus Pound CYP Czech Koruna CZK Danish Krone DKK Estonian Kroon EEK Ecu XEU Euro EUR Finnish Markka FIM French Franc FRF Deutsche Mark DEM Greek Drachma GRD Hungarian Forint HUF Iceland Krona ISK Irish Punt IEP Italian Lira ITL Latvian Lat LVL Lithuanian Litas LTL Luxembourg Franc LUF Macedonia Denar MKD Maltese Lira MTL Moldova Leu MDL Dutch Guilder NLG Norwegian Krone NOK Polish Zloty PLN Portugese Escudo PTE Romanian Leu RON Russian Rouble RUB Slovakian Koruna SKK Slovenian Tolar SIT Spanish Peseta ESP Sterling GBP Swedish Krona SEK Swiss Franc CHF New Turkish Lira TRY Ukraine Hryvnia UAH Serbian Dinar RSD Special Drawing Rights XDR Algerian Dinar DZD Angola Kwanza AOA Bahrain Dinar BHD Botswana Pula BWP Burundi Franc BIF Central African Franc XAF Comoros Franc KMF Congo Democratic Rep. Franc CDF Cote D’Ivorie Franc XOF Egyptian Pound EGP Ethiopia Birr ETB Gambian Dalasi GMD Ghana Cedi GHS Guinea Franc GNF Israeli Shekel ILS Jordanian Dinar JOD Kenyan Schilling KES Kuwaiti Dinar KWD Lebanese Pound LBP Lesotho Loti LSL Malagasy -

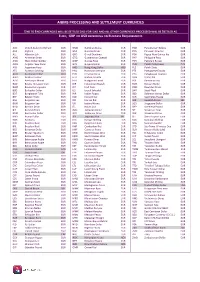

AIBMS Multicurrency List

AIBMS PROCESSING AND SETTLEMENT CURRENCIES END TO END CURRENCIES WILL BE SETTLED LIKE-FOR-LIKE AND ALL OTHER CURRENCIES PROCESSED WILL BE SETTLED AS EURO, GBP OR USD DEPENDING ON BUSINESS REQUIREMENTS AED United Arab Emi Dirham EUR GMD Gambian Dalasi EUR PAB Panamanian Balboa EUR AFA Afghani EUR GNF Guinean Franc EUR PEN Peruvian New Sol EUR ALL Albanian Lek EUR GRD Greek Drachma EUR PGK Papua New Guinea Kia EUR AMD Armenian Dram EUR GTQ Guatemalan Quetzal EUR PHP Philippine Peso EUR ANG West Indian Guilder EUR GWP Guinea Peso EUR PKR Pakistani Rupee EUR AON Angolan New Kwan EUR GYD Guyana Dollar EUR PLN Polish Zloty (new) PLN ARS Argentine Peso EUR HKD Hong Kong Dollar HKD PLZ Polish Zloty EUR ATS Austrian Schilling EUR HNL Honduran Lempira EUR PTE Portuguese Escudo EUR AUD Australian Dollar AUD HRK Croatian Kuna EUR PYG Paraguayan Guarani EUR AWG Aruban Guilder EUR HTG Haitian Gourde EUR QAR Qatar Rial EUR AZM Azerbaijan Manat EUR HUF Hungarian Forint EUR ROL Romanian Leu EUR BAD Bosnia-Herzogovinian EUR IDR Indonesian Rupiah EUR RUB Russian Ruble EUR BAM Bosnia Herzegovina EUR IEP Irish Punt EUR RWF Rwandan Franc EUR BBD Barbados Dollar EUR ILS Israeli Scheckel EUR SAR Saudi Riyal EUR BDT Bangladesh Taka EUR INR Indian Rupee EUR SBD Solomon Islands Dollar EUR BEF Belgian Franc EUR IQD Iraqui Dinar EUR SCR Seychelles Rupee EUR BGL Bulgarian Lev EUR IRR Iranian Rial EUR SEK Swedish Krona SEK BGN Bulgarian Lev EUR ISK Iceland Krona EUR SGD Singapore Dollar EUR BHD Bahrain Dinar EUR ITL Italian Lira EUR SHP St.Helena Pound EUR BIF Burundi -

PRESS KIT Money Euro Banknotes and Coins © European Central Bank,© European 2007

OUR PRESS KIT money Euro banknotes and coins © European Central Bank,© European 2007 Foreword New Year’s Day 2008 will be an historic day for the European Union. On this date, Cyprus and Malta will join Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia and Spain in the euro area and will adopt the euro as their currency. This press kit has been prepared by the European Central Bank to provide the media – and the Cypriot and Maltese media in particular – with comprehensive information about the euro banknotes and coins. The euro will become part of everyday life in Cyprus and Malta at the beginning of next year, and the European Central Bank, the Central Bank of Cyprus and the Central Bank of Malta have a common interest in ensuring that the public is well informed ahead of the changeover. The media’s access to authoritative information and images makes them a major partner in the process of acquainting the public with the euro banknotes and coins and their security features. This press kit provides you with information on the euro changeover in Cyprus and Malta and on the euro banknotes and coins and their security features. We hope it will serve as a useful point of reference for your reporting. I wish you every success in informing the general public about the euro and its banknotes and coins. The knowledge and information you pass on will make a very significant contribution to increasing awareness of the single currency. This is particularly true for the media covering Cyprus and Malta, where your reporting will pave the way for the citizens of those islands to adopt the euro, our money. -

![Guideline: NECC/0001/07 [PDF 90Kb]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0383/guideline-necc-0001-07-pdf-90kb-2060383.webp)

Guideline: NECC/0001/07 [PDF 90Kb]

Guidelines on the undertaking of specific amendments to legislation and on the process of smoothing applicable to the Public Sector in view of the adoption of the euro Guideline: NECC/0001/07 National Euro Changeover Committee (NECC) Version 1.0 Mangion House, Dun Karm Psaila Str Birkirkara th Tel: (+356) 2205 0000 29 March 2007 Fax: (+356) 2205 0001 Email: [email protected] Web: www.euro.gov.mt Guidelines: NECC/0001/07 1. Background In view of Malta’s anticipated entry into the euro area on the 1 January 2008, the Euro Adoption Act (Act X of 2006) was approved by the Maltese Parliament and was published in the Government Gazette on the 25 July 2006. The Act was passed with a view to laying down the overall national legislative framework and the general principles of the conversion process and to providing the required enabling powers for its implementation. Notwithstanding, changes are required to the whole body of Maltese law whereby all references to the Maltese lira and amounts denominated in Lm will have to be changed to their euro equivalent. The implementation of specific amendments to primary acts and legal notices is a major task and needs careful and timely planning. 2. Objective These guidelines outline the process for effecting specific changes to legislation due to the introduction of the euro, taking into account rounding and smoothing requirements for the public sector. The document defines the process to be undertaken, the agreed timeframes, the allocation of responsibilities and the intended outcomes. These guidelines are the result of various discussions and workshops held between representatives from the National Euro Changeover Committee (NECC), the Public Sector Sectoral Committee (PSSC), the Management Efficiency Unit (MEU) within the Office of the Prime Minister, the Public Finance Sectoral Committee (PFSC), the Ministry of Finance (MFIN), the Legal Sector Sectoral Committee (LSSC), the Office of the Attorney General and the Translation and Law Drafting Unit.