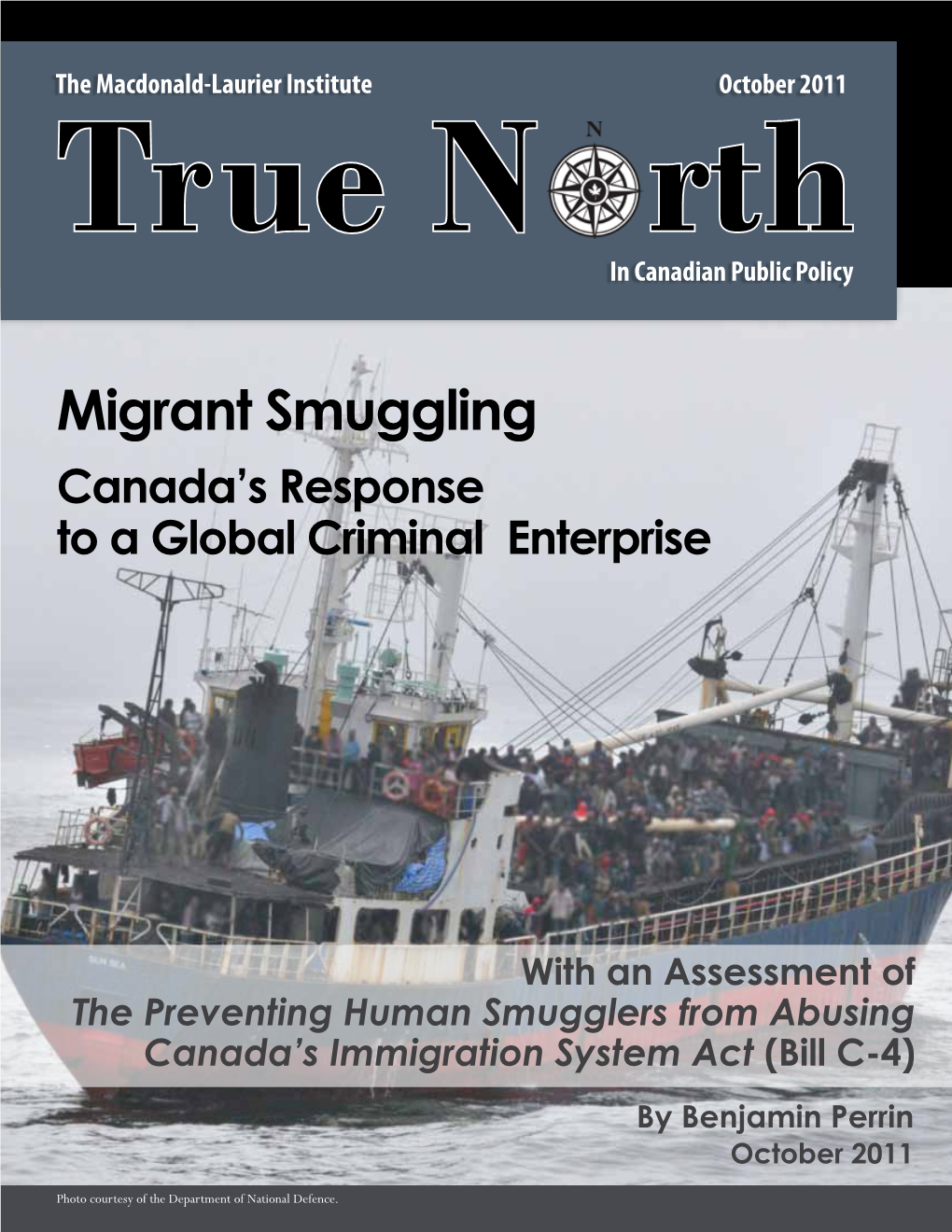

Migrant Smuggling Canada’S Response to a Global Criminal Enterprise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Migrant Smuggling to Canada

Migrant Smuggling to Canada An Enquiry into Vulnerability and Irregularity through Migrant Stories The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. _____________________________ Publisher: International Organization for Migration House No. 10 Plot 48 Osu-Badu Road/Broadway, Airport West IOM Accra, Ghana Tel: +233 302 742 930 Ext. 2400 Fax: +233 302 742 931 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.iom.int Cover photo: An Iraqi refugee who did not want to have his identity revealed stands in Istanbul's commercial district of Gayrettepe during afternoon rush hour. Istanbul districts, such as Aksaray and Beyoglu have been refugee transit hubs since at least the 1979 Iranian Revolution, with subsequent waves including Afghans, Africans, Iraqis and now Syrians. © Iason Athanasiadis, 2017. Recommended citation: International Organization for Migration (IOM)/Samuel Hall, Migrant Smuggling to Canada – An Enquiry into Vulnerability and Irregularity through Migrant Stories, IOM, Accra, Ghana, 2017. -

Jersey's Involvement in the Slave Trade

A RESPECTABLE TRADE OR AGAINST HUMAN DIGNITY? Next year sees the 200th anniversary of the abolition of the slave trade. The Head of Community Learning, Doug Ford, explains that while Jersey and Guernsey were not directly involved, Channel Islands merchants and ships did profit from the transportation of human cargoes across the Atlantic. This 1792 image of Captain John Kember by Isaac Cruickshank was used by the abolitionists to further their cause. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-6204) 4 THE HERITAGE MAGAZINE IN 2007 THE UK CELEBRATES THE BICENTENARY again two months later. During his captivity he was held in of the abolition of the slave trade within what was then the irons and tortured until his family paid a ransom of 600 developing British Empire. As an institution, slavery carried ecus. The mate of the ship died three weeks after being on until 1834, when Parliament finally outlawed the captured and the cabin boy “turned Turk” - converted to practice. Other countries abolished the trade at different Islam to avoid slavery. times until the Brazilians finally ended slavery in 1888 - 37 Another Islander, Richard Dumaresq, held in Salé years after they had prohibited the trade. While Jersey was around the same time, was ransomed following an appeal to not deeply involved in the slave trade, it was involved on the the States by his brothers, Philippe and Jacques and sister, periphery - there was too much money to be made from Marie in May 1627. Sadly, Richard died in 1628 soon after what at the time was regarded as “a perfectly respectable his return to the Island. -

What's New in Washington: 10 Things You Need to Know

Having trouble reading this email? View it in your browser Share This Page March 31, 2017 As the Trump presidency completes its first 10 weeks, the administration is celebrating big wins on the regulatory reform front while nursing some wounds from a major defeat on efforts to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act (ACA). While health care reform is on pause for the moment, Republicans are turning to tax reform as the next major policy priority and continuing to use executive orders (EO) and the Congressional Review Act to roll back Obamaera regulations. Funding for the government expires on April 28, 2017, so Republicans and Democrats will face the first test of bipartisanship in the next few weeks as they seek to fund government agencies, including the Department of Defense, through the end of September. All eyes will be on the Senate next week as the Supreme Court nomination of Judge Neil Gorsuch takes center stage. Here are 10 things that we believe are worth focusing on from the last two weeks: 1. Gorsuch Nomination 2. Possible Repeal of ISP Security Rules 3. TSA’s New Restrictions on Electronic Devices 4. “Energy Independence” Executive Order 5. Secretary Tillerson in Asia 6. Bilateral Trade and NAFTA Renegotiations 7. FDA User Fees Reauthorization 8. Fiduciary Rule 9. USTR Reports 10. Congressional Appropriations Preview Gorsuch Nomination Amid pressure from his leftleaning base, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (DNY) stepped up his opposition to the nomination of Judge Neil Gorsuch to fill the late Justice Antonin Scalia’s seat on the Supreme Court. -

Irregular Migration, Trafficking and Smuggling of Human Beings in EU Law and Policy

This book examines the treatment of irregular migration, trafficking and smuggling of human beings in EU law and policy. What are the policy dilemmas encountered in efforts to criminalise irregular migration and humanitarian assistance to irregular immigrants ? The various contributions in this edited Irregular Migration, volume examine the principal considerations that make up EU policies directed towards irregular migration and its relationship with trafficking and smuggling of human beings. This book aims Trafficking and to provide academic input to informed policy-making in the next phase of the European Agenda on Migration. smuggling of human beings Policy Dilemmas in the EU Centre for European Policy Studies 1 Place du Congrès 1000 Brussels, Belgium Tel : 32(0)2.229.39.11 Fax : 32(0)2.219.41.51 E-mail : [email protected] Website : www.ceps.eu IRREGULAR TRAFFICKING MIGRATION, OF HUMAN ANDBEINGS SMUGGLING Edited by Sergio Carrera CEPS Elspeth Guild IRREGULAR MIGRATION, TRAFFICKING AND SMUGGLING OF HUMAN BEINGS IRREGULAR MIGRATION, TRAFFICKING AND SMUGGLING OF HUMAN BEINGS POLICY DILEMMAS IN THE EU EDITED BY SERGIO CARRERA AND ELSPETH GUILD FOREWORD BY MATTHIAS RUETE CENTRE FOR EUROPEAN POLICY STUDIES (CEPS) BRUSSELS The Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) is an independent policy research institute in Brussels. Its mission is to produce sound policy research leading to constructive solutions to the challenges facing Europe. The views expressed in this book are entirely those of the authors and should not be attributed to CEPS or any other institution with which they are associated or to the European Union. This book falls within the framework of FIDUCIA (New European Crimes and Trust-based Policy), a research project financed by the European Commission under the Seventh Framework Programme, which ran from 2012-15. -

The Annexation of Algiers, 1870

Cityscapes: A Geographer's View of the New Orleans Area The Annexation of Algiers Richard Campanella, published in the New Orleans Times-Picayune, August 11, 2017 Drone photo of Algiers by Lorenzo Serafini Boni, March 2017 Algiers has a complicated insider/outsider relationship with New Orleans. The neighborhood— or is it a district, a region, a river bank?—has been both sibling and offspring of its world-renown neighbor, at once near and far from it. Depending on one’s definition of urbanism, Algiers may be described as either older or younger than the historic faubourgs across the river: initial development occurred in 1719, a year after the city’s founding, but the surveying of today’s Algiers Point street grid did not occur until well into the 1800s. The complexity deepens jurisdictionally. Algiers was at first outside of New Orleans, then inside parish limits but outside city limits. Since 1870 it’s been inside both parish and city limits—yet seemingly still apart. Indeed, the very name “Algiers” alludes to its liminality. Some say the appellation originated with veterans of Spain’s expedition against Algeria, who while serving in Spanish New Orleans were reminded of the North African city of Algiers on the Mediterranean when they saw this outpost on the Mississippi. There are other stories: that “Algiers” derives from the enslaved Africans encamped there, or from the piracy and smuggling activity associated with the Barbary Coast. Whatever the origins, it’s been called Algiers for well over 200 years. The Kings Plantation, future Algiers, is marked on this 1765 English map, courtesy Library of Congress. -

Listening to the RUMRUNNERS: Radio Intelligence During Prohibition This Publication Is a Product of the National Security Agency History Program

Listening to the RUMRUNNERS: Radio Intelligence during Prohibition This publication is a product of the National Security Agency history program. It presents a historical perspective for informational and educational purposes, is the result of independent research, and does not necessarily reflect a position of NSA/CSS or any other U.S. government entity. This publication is distributed free by the National Security Agency. If you would like additional copies, please email your request to [email protected] or write to: Center for Cryptologic History National Security Agency 9800 Savage Road, Suite 6886 Fort George G. Meade, MD 20755-6886 David Mowry served as a historian, researching and writing histories in the Cryptologic History Series. He began his Agency career as a linguist in 1957 and later (1964-1969) held positions as a linguist and cryptanalyst. From 1969 through 1981 he served in various technical and managerial positions. In the latter part of his career, he was a historian in the Center for Cryptologic History. Mr. Mowry held a BA with regional group major in Germany and Central Europe from the University of California at Berkeley. He passed away in 2005. Cover: The U.S. Coast Guard 75-ft. patrol boat CG-262 towing into San Francisco Harbor her prizes, the tug ELCISCO and barge Redwood City, seized for violation of U.S. Customs laws, in 1927. From Rum War: The U.S. Coast Guard and Prohibition. Listening to the Rumrunners: Radio Intelligence during Prohibition David P. Mowry Center for Cryptologic History Second edition 2014 A motorboat makes contact with the liquor-smuggling British schooner Katherine off the New Jersey coast, 1923. -

UNODC Multi-Country Study on Trafficking in Persons and Smuggling of Migrants from Nepal

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Regional Office for SouthAsia September 2019 Copyright © UNODC 2019 Disclaimer: The designations employed and the contents of this publication, do not imply the expression or endorsement of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNODC concerning the legal status of any country, territory or city, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. EP 16/17, Chandragupta Marg, Chanakyapuri New Delhi - 110021, India Tel: +91 11 24104964/66/68 Website: www.unodc. org/southasia/ Follow UNODC South Asia on: This is an internal UNODC document, which is not meant for wider public distribution and is a component of ongoing, expert research undertaken by the UNODC under the GLO.ACT project. The objective of this study is to identify pressing needs and offer strategic solutions to support the Government of Nepal and its law enforcement agencies in areas covered by UNODC mandates, particularly the smuggling of migrants. This report has not been formally edited, and its contents do not necessarily reflect or imply endorsement of the views or policies of the UNODC or any contributory organizations. In addition, the designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply any particular opinion whatsoever regarding the legal status of any country, territory, municipality or its authorities, or the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The boundaries and names shown, and the designations used in all the maps in this report, do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations and the UNODC. TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 3 ABBREVIATIONS 4 KEY TERMS USED IN THE REPORT AND THEIR DEFINITIONS/MEANINGS 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 1. -

Smuggling of Migrants — the Harsh Search for a Better Life

FACTS Smuggling of migrants — The harsh search for a better life The smuggling of migrants is a truly global concern, with a The profiles of the smugglers vary widely. Full-time professional large number of countries affected by it as origin, transit or criminals are involved in smuggling migrants around the world; destination points. Profit-seeking criminals smuggle migrants some of those criminals are specialized in smuggling people, across borders and between continents. Assessing the real size and some are not. There is evidence of both smaller and larger, of this crime is a complex matter, owing to its underground more organized groups and networks operating as smugglers nature and the difficulty of identifying when irregular migra- in all areas, although this varies by region and route. There are tion is being facilitated by smugglers. Smugglers take advan- also many smugglers who run legitimate businesses and are tage of the large number of migrants willing to take risks in involved in the smuggling of migrants as opportunistic carri- search of a better life when they cannot access legal channels ers or hospitality providers who choose to look the other way of migration. in order to make some extra money. Corrupt officials and other individuals may also be involved in the process. Smuggled migrants are vulnerable to abuse and exploitation. Their safety and even their lives are often put at risk: they may Smugglers of migrants are becoming more and more organized, suffocate in containers, perish in deserts or drown at sea while establishing professional networks that transcend borders and being smuggled by profit-seeking criminals who treat them as encompass all regions. -

Glossary on Migration the Opinions Expressed in This Glossary Do Not Necessarily Reflect the Views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM)

N° 34 INTERNATIONAL MIGRATION LAW Glossary on Migration The opinions expressed in this Glossary do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well‐being of migrants. Publisher: International Organization for Migration 17 route des Morillons P.O. Box 17 1211 Geneva 19 Switzerland Phone: + 41 22 717 91 11 Fax: + 41 22 798 61 50 Email: [email protected] Website: www.iom.int ____________________________________________________ ISSN 1813‐2278 © 2019 International Organization for Migration (IOM) _____________________________________________________ All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. 71_18 (230420) N° 34 INTERNATIONAL MIGRATION LAW Glossary on Migration Glossary on Migration First foreword Effective cooperation among relevant actors is probably more important in the migration field than in any other policy areas. Not only do States sometimes speak different languages when dealing with migration, but also actors within the same State often use an inconsistent vocabulary. -

Action Knowledge Transfer on Migrant Smuggling and Trafficking by Air and Document Fraud ____

Action Knowledge Transfer on Migrant Smuggling and Trafficking by Air and Document Fraud ____ March 2019 Clara Alberola Chiara Janssen 1 This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union, contracted by ICMPD through the Mobility Partnership Facility. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union and the one of ICMPD. Table of Contents List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................ 3 List of Figures .......................................................................................................................................... 4 List of abbreviations ................................................................................................................................ 5 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 6 Executive summary ................................................................................................................................. 7 Part 1: Presentation of the study ........................................................................................................... 10 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 10 2. Objectives -

In the Smuggling of Migrants Protocol

Issue Paper The Concept of “Financial or Other Material Benefit” in the Smuggling of Migrants Protocol UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna The Concept of “Financial or Other Material Benefit” in the Smuggling of Migrants Protocol Issue Paper UNITED NATIONS New York, 2017 The description and classification of countries and territories in this study and the arrangement of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authori- ties, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or regarding its economic system or degree of development. This publication has not been formally edited. © United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2017. All rights reserved, worldwide. Publishing production: English, Publishing and Library Section, United Nations Office at Vienna. Preface As the guardian of the United Nations Transnational Organized Crime Convention and the Protocols thereto, UNODC is mandated to support States Parties in efforts to fulfill their obligations under these instruments. It is in this context that we present this Issue Paper on the “financial or other material benefit” element of the international legal definition of smuggling of migrants as set out in the Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (Smuggling of Migrants Protocol). This study follows earlier work undertaken by UNODC to elaborate guidance on concepts contained in the definition of human trafficking. The series of Issue Papers that were produced on the basis of that work have been welcomed by States Parties to the Protocol on Trafficking in Persons Especially Women and Children supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime and have been used in developing new laws and interpreting existing ones. -

Florida's Peculiar Status During Prohibition

The Journal of The James Madison Institute The Journal of The James Madison Institute Prohibitionists’ Domain and Smugglers’ Paradise: Florida’s Peculiar Status During Prohibition | Lauren Sumners Editor’s Note: A version of this article originally appeared on Florida Verve, The James Madison Institute’s website devoted to Florida’s arts and culture. he U.S. Constitution’s 18th Millions of Americans chose to Amendment had taken effect at the drink anyway, so the demand for booze beginning of the Roaring Twenties. had to be satisfied through illegal means TThen hailed as a “noble experiment” but that included bootlegging, smuggling, later viewed as a colossal mistake that speakeasies, and the illegal production spawned all sorts of crime, the so-called of alcoholic beverages ranging from “Prohibition Amendment” told a thirsty moonshine whiskey to bathtub gin. nation, “Don’t drink!” During this tumultuous decade, www.jamesmadison.org | 91 The Journal of The James Madison Institute The Journal of The James Madison Institute Florida elected as its Governor a preacher Florida counties along the 250-mile long named Sidney J. Catts, the candidate of stretch of coastline from Titusville in the Prohibition Party, and became the northern Brevard County to Florida City 15th state to ratify the 18th Amendment near the southern border of Dade (now in 1918. Ironic since Florida was also in Miami-Dade) County, had a combined the thick of the aforementioned illegal population of only 82,843, with more than activities, gaining nationwide notoriety half of the population clustered in the as a hotbed of smuggling. These illegal Miami area.