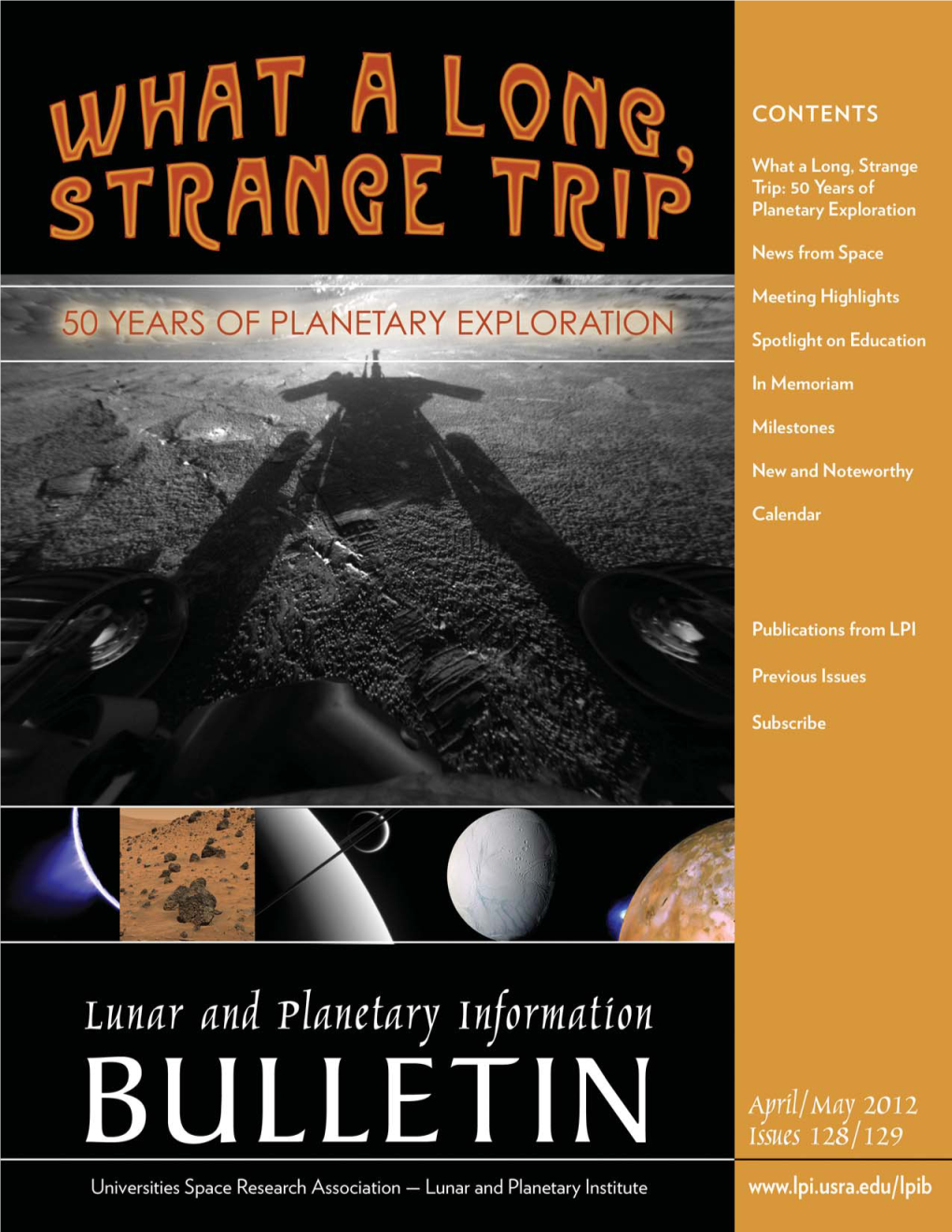

LPIB Issues 128/129

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soyuz TMA-11 / Expedition 16 Manuel De La Mission

Soyuz TMA-11 / Expedition 16 Manuel de la mission SOYUZ TMA-11 – EXPEDITION 16 Par Philippe VOLVERT SOMMAIRE I. Présentation des équipages II. Présentation de la mission III. Présentation du vaisseau Soyuz IV. Précédents équipages de l’ISS V. Chronologie de lancement VI. Procédures d’amarrage VII. Procédures de retour VIII. Horaires IX. Sources A noter que toutes les heures présentes dans ce dossier sont en heure GMT. I. PRESENTATION DES EQUIPAGES Equipage Expedition 15 Fyodor YURCHIKHIN (commandant ISS) Lieu et Lieu et date de naissance : 03/01/1959 ; Batumi (Géorgie) Statut familial : Marié et 2 enfants Etudes : Graduat d’économie à la Moscow Service State University Statut professionnel: Ingénieur et travaille depuis 1993 chez RKKE Roskosmos : Sélectionné le 28/07/1997 (RKKE-13) Précédents vols : STS-112 (07/10/2002 au 18/10/2002), totalisant 10 jours 19h58 Oleg KOTOV(ingénieur de bord) Lieu et date de naissance : 27/10/1965 ; Simferopol (Ukraine) Statut familial : Marié et 2 enfants Etudes : Doctorat en médecine obtenu à la Sergei M. Kirov Military Medicine Academy Statut professionnel: Colonel, Russian Air Force et travaille au centre d’entraînement des cosmonautes, le TsPK Roskosmos : Sélectionné le 09/02/1996 (RKKE-12) Précédents vols : - Clayton Conrad ANDERSON (Ingénieur de vol ISS) Lieu et date de naissance : 23/02/1959 ; Omaha (Nebraska) Statut familial : Marié et 2 enfants Etudes : Promu bachelier en physique à Hastings College, maîtrise en ingénierie aérospatiale à la Iowa State University Statut professionnel: Directeur du centre des opérations de secours à la Nasa Nasa : Sélectionné le 04/06/1998 (Groupe) Précédents vols : - Equipage Expedition 16 / Soyuz TM-11 Peggy A. -

Fstate Scientist: Omond Mckillop Solandt and Government Science

fState Scientist: Omond McKillop Solandt and Government Science in War and Hostile Peace, 1939-1956/ Scientifique.de l'Etat: Omond McKillop Solandt et la Science du Gouvernement lors de la Guerre et de la Paix Hostile, 1939-1956 A Thesis Submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies of the Royal Military College of Canada by Jason Sean Ridler, MA Royal Military College of Canada, 2001 BA (Hons.) York University, 1999 In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2008 ©This thesis may be used within the Department of National Defence but copyright for open publication remains the property of the author. Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-47901-8 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-47901-8 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. -

Mission to Jupiter

This book attempts to convey the creativity, Project A History of the Galileo Jupiter: To Mission The Galileo mission to Jupiter explored leadership, and vision that were necessary for the an exciting new frontier, had a major impact mission’s success. It is a book about dedicated people on planetary science, and provided invaluable and their scientific and engineering achievements. lessons for the design of spacecraft. This The Galileo mission faced many significant problems. mission amassed so many scientific firsts and Some of the most brilliant accomplishments and key discoveries that it can truly be called one of “work-arounds” of the Galileo staff occurred the most impressive feats of exploration of the precisely when these challenges arose. Throughout 20th century. In the words of John Casani, the the mission, engineers and scientists found ways to original project manager of the mission, “Galileo keep the spacecraft operational from a distance of was a way of demonstrating . just what U.S. nearly half a billion miles, enabling one of the most technology was capable of doing.” An engineer impressive voyages of scientific discovery. on the Galileo team expressed more personal * * * * * sentiments when she said, “I had never been a Michael Meltzer is an environmental part of something with such great scope . To scientist who has been writing about science know that the whole world was watching and and technology for nearly 30 years. His books hoping with us that this would work. We were and articles have investigated topics that include doing something for all mankind.” designing solar houses, preventing pollution in When Galileo lifted off from Kennedy electroplating shops, catching salmon with sonar and Space Center on 18 October 1989, it began an radar, and developing a sensor for examining Space interplanetary voyage that took it to Venus, to Michael Meltzer Michael Shuttle engines. -

The Space Impact of the Euro Crisis 50 Years After Mariner 2: Exploration at a Crossroads

0827_SPN_DOM_00_019_00 (READ ONLY) 8/24/2012 11:39 AM Page 19 www.spacenews.com SPACENEWS 19 August27, 2012 TheSpaceImpact of the Euro Crisis < ROBBIN LAIRD and HARALD MALMGREN > he European sovereign debt crisis Europe will now be challenged in the ing to hide the reality of European bank of the savings of millions of European is not simply abump in historical form of rollbacks of the many inter- weaknesses. The main reason is that eu- citizens. Tprogress; it is the end of aperiod twined strands of integration, fraying rozone economies are far more bank- European leaders are also attempt- of historyand acritical point in Euro- what has been an intricate but incom- dependent than economies like those in ing to initiate amore comprehensive fis- pean and global transition in the 21st plete tapestry. It is questionable whether the United States or United Kingdom, cal union, with new decision-making century. Europe will be able to prevent stalling of where substantial nonbank financing al- mechanisms that transfer sovereignty in The confluence of several trend lines the integration process in the face of ternatives exist for the corporate sector. parallel with the new banking union. We — the unification of Germany,the end widening gaps among the interests of In the eurozone, banks are the fi- do not believe that any of the eurozone of the Soviet Union, the collapse of the each nation and even within each nation. nancial markets; in the U.S., banks are governments are ready for such apoliti- Berlin Wall, the expansion of NATO, Since the birth of the euro, the but one segment of amultifaceted fi- cal transition in which citizens in each the expansion of the European Union French and Germans were in the lead in nancial market. -

Plans for Human Exploration Beyond Low Earth Orbit

National Aeronautics and Space Administration ESMD Overview: Imagining a Vibrant Future for Human Exploration of Space Laurie Leshin, Deputy AA ESMD April 6, 2011 A New Path: The NASA Authorization Act of 2010 • The Congress approved and the President signed the National Aeronautics and Space Administration Authorization Act of 2010 – Bipartisan support for human exploration beyond Low Earth Orbit • The law authorizes: – Extension of the International Space Station until at least 2020 – Strong support for a commercial space transportation industry – Development of a multi-purpose Crew Vehicle and heavy lift launch capabilities – A “capabilities-driven” approach to space exploration opening up vast opportunities including near-Earth asteroids (NEA), the Moon, and Mars – New space technology investments to increase the capabilities beyond low Earth orbit 2 Briefing to the NASA Chief Scientist Destinations for Expansion of Humans Into the Solar System Enabled by FY 2012 Investments Key 3 A Bounty of Opportunity for Human Explorers Mars and its Moons: – A premier destination for discovery: Is there life beyond Earth? How did Mars evolve? – True possibility for extended, even permanent, stays – Significant opportunities for international collaboration HEO/GEO/Lagrange Points: – Technological driver for space – Microgravity destinations beyond LEO systems – Opportunities for construction, fueling and repair of complex in-space systems – Excellent locations for advanced space telescopes and Earth observers Earth’s Moon: Near Earth Asteroids: -

Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter

Chapter 6 Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter Jim Taylor, Dennis K. Lee, and Shervin Shambayati 6.1 Mission Overview The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) [1, 2] has a suite of instruments making observations at Mars, and it provides data-relay services for Mars landers and rovers. MRO was launched on August 12, 2005. The orbiter successfully went into orbit around Mars on March 10, 2006 and began reducing its orbit altitude and circularizing the orbit in preparation for the science mission. The orbit changing was accomplished through a process called aerobraking, in preparation for the “science mission” starting in November 2006, followed by the “relay mission” starting in November 2008. MRO participated in the Mars Science Laboratory touchdown and surface mission that began in August 2012 (Chapter 7). MRO communications has operated in three different frequency bands: 1) Most telecom in both directions has been with the Deep Space Network (DSN) at X-band (~8 GHz), and this band will continue to provide operational commanding, telemetry transmission, and radiometric tracking. 2) During cruise, the functional characteristics of a separate Ka-band (~32 GHz) downlink system were verified in preparation for an operational demonstration during orbit operations. After a Ka-band hardware anomaly in cruise, the project has elected not to initiate the originally planned operational demonstration (with yet-to-be used redundant Ka-band hardware). 201 202 Chapter 6 3) A new-generation ultra-high frequency (UHF) (~400 MHz) system was verified with the Mars Exploration Rovers in preparation for the successful relay communications with the Phoenix lander in 2008 and the later Mars Science Laboratory relay operations. -

University of Iowa Instruments in Space

University of Iowa Instruments in Space A-D13-089-5 Wind Van Allen Probes Cluster Mercury Earth Venus Mars Express HaloSat MMS Geotail Mars Voyager 2 Neptune Uranus Juno Pluto Jupiter Saturn Voyager 1 Spaceflight instruments designed and built at the University of Iowa in the Department of Physics & Astronomy (1958-2019) Explorer 1 1958 Feb. 1 OGO 4 1967 July 28 Juno * 2011 Aug. 5 Launch Date Launch Date Launch Date Spacecraft Spacecraft Spacecraft Explorer 3 (U1T9)58 Mar. 26 Injun 5 1(U9T68) Aug. 8 (UT) ExpEloxrpelro r1e r 4 1915985 8F eJbu.l y1 26 OEGxOpl o4rer 41 (IMP-5) 19697 Juunlye 2 281 Juno * 2011 Aug. 5 Explorer 2 (launch failure) 1958 Mar. 5 OGO 5 1968 Mar. 4 Van Allen Probe A * 2012 Aug. 30 ExpPloiorenre 3er 1 1915985 8M Oarc. t2. 611 InEjuxnp lo5rer 45 (SSS) 197618 NAouvg.. 186 Van Allen Probe B * 2012 Aug. 30 ExpPloiorenre 4er 2 1915985 8Ju Nlyo 2v.6 8 EUxpKlo 4r e(rA 4ri1el -(4IM) P-5) 197619 DJuenc.e 1 211 Magnetospheric Multiscale Mission / 1 * 2015 Mar. 12 ExpPloiorenre 5e r 3 (launch failure) 1915985 8A uDge.c 2. 46 EPxpiolonreeerr 4130 (IMP- 6) 19721 Maarr.. 313 HMEaRgCnIe CtousbpeShaetr i(cF oMxu-1ltDis scaatelell itMe)i ssion / 2 * 2021081 J5a nM. a1r2. 12 PionPeioenr e1er 4 1915985 9O cMt.a 1r.1 3 EExpxlpolorerer r4 457 ( S(IMSSP)-7) 19721 SNeopvt.. 1263 HMaalogSnaett oCsupbhee Sriact eMlluitlet i*scale Mission / 3 * 2021081 M5a My a2r1. 12 Pioneer 2 1958 Nov. 8 UK 4 (Ariel-4) 1971 Dec. 11 Magnetospheric Multiscale Mission / 4 * 2015 Mar. -

SPEAKERS TRANSPORTATION CONFERENCE FAA COMMERCIAL SPACE 15TH ANNUAL John R

15TH ANNUAL FAA COMMERCIAL SPACE TRANSPORTATION CONFERENCE SPEAKERS COMMERCIAL SPACE TRANSPORTATION http://www.faa.gov/go/ast 15-16 FEBRUARY 2012 HQ-12-0163.INDD John R. Allen Christine Anderson Dr. John R. Allen serves as the Program Executive for Crew Health Christine Anderson is the Executive Director of the New Mexico and Safety at NASA Headquarters, Washington DC, where he Spaceport Authority. She is responsible for the development oversees the space medicine activities conducted at the Johnson and operation of the first purpose-built commercial spaceport-- Space Center, Houston, Texas. Dr. Allen received a B.A. in Speech Spaceport America. She is a recently retired Air Force civilian Communication from the University of Maryland (1975), a M.A. with 30 years service. She was a member of the Senior Executive in Audiology/Speech Pathology from The Catholic University Service, the civilian equivalent of the military rank of General of America (1977), and a Ph.D. in Audiology and Bioacoustics officer. Anderson was the founding Director of the Space from Baylor College of Medicine (1996). Upon completion of Vehicles Directorate at the Air Force Research Laboratory, Kirtland his Master’s degree, he worked for the Easter Seals Treatment Air Force Base, New Mexico. She also served as the Director Center in Rockville, Maryland as an audiologist and speech- of the Space Technology Directorate at the Air Force Phillips language pathologist and received certification in both areas. Laboratory at Kirtland, and as the Director of the Military Satellite He joined the US Air Force in 1980, serving as Chief, Audiology Communications Joint Program Office at the Air Force Space at Andrews AFB, Maryland, and at the Wiesbaden Medical and Missile Systems Center in Los Angeles where she directed Center, Germany, and as Chief, Otolaryngology Services at the the development, acquisition and execution of a $50 billion Aeromedical Consultation Service, Brooks AFB, Texas, where portfolio. -

Mourners Remember Life, Career of US Astronaut John Glenn 17 December 2016

Mourners remember life, career of US astronaut John Glenn 17 December 2016 Mourners gathered at a memorial service for The state of Ohio held ceremonies over two days, groundbreaking astronaut John Glenn on Saturday complete with full military honors, ending with the in his home state of Ohio, capping two days of memorial service held at a 2,500-seat auditorium remembrances for the first American to orbit the on the Ohio State University campus home to the Earth. Glenn College of Public Affairs. Glenn, who later in life also became the first senior The memorial service was attended by dignitaries, citizen in space, was remembered as a national high-ranking government officials and members of hero who believed in selfless service to his the public who got tickets. country. The service included a platoon of 40 Marines who He died last week at the age of 95, after a lifetime marched three miles (4.8 kilometers) to accompany spent in the US Marines, the American space the hearse carrying Glenn's body from the Ohio program, the Senate, and as a university Statehouse to the auditorium. professor. Glenn's flag-draped coffin lay in state at the At the public memorial service in the state capital Statehouse rotunda Friday, allowing thousands of Columbus, Vice President Joe Biden said Glenn visitors to pay their final respects in an honor exemplified America's view of itself as a "country of granted to only eight other people in Ohio's history. promise, opportunity, always a belief for tomorrow." At the memorial, speakers—including his adult children Lyn and David—remembered Glenn's long "He knew from his upbringing that ordinary career in public service. -

Remains of Astronaut Legend Neil Armstrong Buried at Sea 15 September 2012

Remains of astronaut legend Neil Armstrong buried at sea 15 September 2012 The cremated remains of legendary American astronaut Neil Armstrong were scattered at sea Friday, in a ceremony aboard a US aircraft carrier paying final tribute to the first man to set foot on the moon, NASA said. US Navy personnel carried Armstrong's remains to the Atlantic Ocean one day after a somber memorial ceremony at the Washington National Cathedral for the famously reserved Apollo 11 commander, who died August 25 at the age of 82. Armstrong's widow Carol was presented an American flag at the ceremony aboard the USS Philippine Sea that included a bugler and rifle salute. "Neil will always be remembered for taking humankind's first small step on another world," NASA Administrator Charles Bolden said at the National Cathedral service. "But it was the courage, grace and humility he displayed throughout his life that lifted him above the stars." Armstrong's Apollo 11 crew mates Michael Collins and Buzz Aldrin, Eugene Cernan—the Apollo 17 mission commander and last man to walk on the moon—attended the memorial service. Also present Thursday was John Glenn, the former US senator and first American to orbit the Earth. Armstrong came to be known around the world for the immortal words he uttered on July 20, 1969, as he became the first person ever to step onto another body in space: "That's one small step for (a) man, one giant leap for mankind." (c) 2012 AFP APA citation: Remains of astronaut legend Neil Armstrong buried at sea (2012, September 15) retrieved 29 September 2021 from https://phys.org/news/2012-09-astronaut-legend-neil-armstrong-sea.html 1 / 2 This document is subject to copyright. -

Topographic Power Spectra of Cratered Terrains: 10.1002/2014JE004746 Theory and Application to the Moon

JournalofGeophysicalResearch: Planets RESEARCH ARTICLE Topographic power spectra of cratered terrains: 10.1002/2014JE004746 Theory and application to the Moon Key Points: Margaret A. Rosenburg1, Oded Aharonson2, and Re’em Sari3 • Impact cratering produces characteristic variations in the 1Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California, USA, 2Department topographic PSD of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Weizmann Institute of Technology, Rehovot, Israel, 3Racah Institute of Physics, Hebrew • The size-frequency distribution and shape of craters control University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel PSD variations • We investigate the topographic PSD on model terrains and Impact cratering produces characteristic variations in the topographic power spectral density lunar topography Abstract (PSD) of cratered terrains, which are controlled by the size-frequency distribution of craters and the spectral content (shape) of individual features. These variations are investigated here in two parallel Correspondence to: approaches. First, a cratered terrain model, based on Monte Carlo emplacement of craters and benchmarked M. A. Rosenburg, [email protected] by an analytical formulation of the one-dimensional PSD, is employed to generate topographic surfaces at a range of size-frequency power law exponents and shape dependencies. For self-similar craters, the slope of the PSD, , varies inversely with that of the production function, , leveling off to 0 at high (surface Citation: Rosenburg, M. A., O. Aharonson, topography dominated by the smallest craters) and maintaining a roughly constant value ( ∼ 2) at low and R. Sari (2015), Topographic (surface topography dominated by the largest craters). The effects of size-dependent shape parameters power spectra of cratered terrains: and various crater emplacement rules are also considered. -

Raptis-Rare-Books-Digital-Holiday

1 FOR THE COLLECTION OF A LIFETIME The process of creating one’s personal library is the pursuit of a lifetime. It requires special thought and consideration. Each book represents a piece of history, and it is a remarkable task to assemble these individual items into a collection. Our aim at Raptis Rare Books is to render tailored, individualized service to help you achieve your goals. We specialize in working with private collectors with a specific wish list, helping individuals find the ideal gift for special occasions, and partnering with representatives of institutions. We are here to assist you in your pursuit. Thank you for letting us be your guide in bringing the library of your imagination to reality. FOR MORE INFORMATION For further details regarding any of the items featured in these pages, visit our website or call 561-508-3479 for expert assistance from one of our booksellers. Raptis Rare Books | 226 Worth Avenue | Palm Beach, Florida 33480 561-508-3479 | [email protected] www.RaptisRareBooks.com Contents History, Philosophy & Religion..........................................................................2 American History...............................................................................................10 Literature.............................................................................................................24 Heroes and Leaders.............................................................................................40 Travel, Adventure and Sport.............................................................................54