Ice Segregation As an Origin for Lenses of Non-Glacial Ice in •Œice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

River Ice Management in North America

RIVER ICE MANAGEMENT IN NORTH AMERICA REPORT 2015:202 HYDRO POWER River ice management in North America MARCEL PAUL RAYMOND ENERGIE SYLVAIN ROBERT ISBN 978-91-7673-202-1 | © 2015 ENERGIFORSK Energiforsk AB | Phone: 08-677 25 30 | E-mail: [email protected] | www.energiforsk.se RIVER ICE MANAGEMENT IN NORTH AMERICA Foreword This report describes the most used ice control practices applied to hydroelectric generation in North America, with a special emphasis on practical considerations. The subjects covered include the control of ice cover formation and decay, ice jamming, frazil ice at the water intakes, and their impact on the optimization of power generation and on the riparians. This report was prepared by Marcel Paul Raymond Energie for the benefit of HUVA - Energiforsk’s working group for hydrological development. HUVA incorporates R&D- projects, surveys, education, seminars and standardization. The following are delegates in the HUVA-group: Peter Calla, Vattenregleringsföretagen (ordf.) Björn Norell, Vattenregleringsföretagen Stefan Busse, E.ON Vattenkraft Johan E. Andersson, Fortum Emma Wikner, Statkraft Knut Sand, Statkraft Susanne Nyström, Vattenfall Mikael Sundby, Vattenfall Lars Pettersson, Skellefteälvens vattenregleringsföretag Cristian Andersson, Energiforsk E.ON Vattenkraft Sverige AB, Fortum Generation AB, Holmen Energi AB, Jämtkraft AB, Karlstads Energi AB, Skellefteå Kraft AB, Sollefteåforsens AB, Statkraft Sverige AB, Umeå Energi AB and Vattenfall Vattenkraft AB partivipates in HUVA. Stockholm, November 2015 Cristian -

Contemporary Periglacial Processes in the Swiss Alps: Seasonal, Inter-Annual and Long-Term Variations

Permafrost, Phillips, Springman & Arenson (eds) © 2003 Swets & Zeitlinger, Lisse, ISBN 90 5809 582 7 Contemporary periglacial processes in the Swiss Alps: seasonal, inter-annual and long-term variations N. Matsuoka & A. Ikeda Institute of Geoscience, University of Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan K. Hirakawa & T. Watanabe Graduate School of Environmental Earth Science, Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan ABSTRACT: Comprehensive monitoring of periglacial weathering and mass wasting has been undertaken near the lower limit of the mountain permafrost belt. Seven years of monitoring highlight both seasonal and inter- annual variations. On the seasonal scale, three types of movements are identified: (A) small magnitude events associated with diurnal freeze-thaw cycles, (B) larger events during early seasonal freezing and (C) sporadic events originating from refreezing of meltwater during seasonal thawing. Type A produces pebbles or smaller fragments from rockwalls and shallow (Ͻ10 cm) frost creep on debris slopes. Types B and C are responsible for larger debris production and deeper (Ͻ50 cm) frost creep/gelifluction. Some of these events contribute to perma- nent opening of rock joints and advance of solifluction lobes. Sporadic large boulder falls enhance inter-annual variation in rockwall retreat rates. On some debris slopes, prolonged snow melting occasionally triggers rapid soil flow, which causes inter-annual variation in rates of soil movement. 1 INTRODUCTION 9º40'E 10º00'E Piz Kesch Real-time monitoring of periglacial slope processes is 3418 Switzerland useful to predict ongoing slope instability problems in Inn alpine regions. Such a prediction, however, needs long- Piz d'Err Piz Ot term variations in slope processes caused by climate 3378 3246 Samedan Italia change to be distinguished from inter-annual scale vari- A 30'E 30'E º St. -

Airplane Icing

Federal Aviation Administration Airplane Icing Accidents That Shaped Our Safety Regulations Presented to: AE598 UW Aerospace Engineering Colloquium By: Don Stimson, Federal Aviation Administration Topics Icing Basics Certification Requirements Ice Protection Systems Some Icing Generalizations Notable Accidents/Resulting Safety Actions Readings – For More Information AE598 UW Aerospace Engineering Colloquium Federal Aviation 2 March 10, 2014 Administration Icing Basics How does icing occur? Cold object (airplane surface) Supercooled water drops Water drops in a liquid state below the freezing point Most often in stratiform and cumuliform clouds The airplane surface provides a place for the supercooled water drops to crystalize and form ice AE598 UW Aerospace Engineering Colloquium Federal Aviation 3 March 10, 2014 Administration Icing Basics Important Parameters Atmosphere Liquid Water Content and Size of Cloud Drop Size and Distribution Temperature Airplane Collection Efficiency Speed/Configuration/Temperature AE598 UW Aerospace Engineering Colloquium Federal Aviation 4 March 10, 2014 Administration Icing Basics Cloud Characteristics Liquid water content is generally a function of temperature and drop size The colder the cloud, the more ice crystals predominate rather than supercooled water Highest water content near 0º C; below -40º C there is negligible water content Larger drops tend to precipitate out, so liquid water content tends to be greater at smaller drop sizes The average liquid water content decreases with horizontal -

Overview of Icing Research at NASA Glenn

Overview of Icing Research at NASA Glenn Eric Kreeger NASA Glenn Research Center Icing Branch 25 February, 2013 Glenn Research Center at Lewis Field Outline • The Icing Problem • Types of Ice • Icing Effects on Aircraft Performance • Icing Research Facilities • Icing Codes Glenn Research Center at Lewis Field 2 Aircraft Icing Ground Icing Ice build-up results in significant changes to the aerodynamics of the vehicle This degrades the performance and controllability of the aircraft In-Flight Icing Glenn Research Center at Lewis Field 3 3 Aircraft Icing During an in-flight encounter with icing conditions, ice can build up on all unprotected surfaces. Glenn Research Center at Lewis Field 4 Recent Commercial Aircraft Accidents • ATR-72: Roselawn, IN; October 1994 – 68 fatalities, hull loss – NTSB findings: probable cause of accident was aileron hinge moment reversal due to an ice ridge that formed aft of the protected areas • EMB-120: Monroe, MI; January 1997 – 29 fatalities, hull loss – NTSB findings: probable cause of accident was loss-of-control due to ice contaminated wing stall • EMB-120: West Palm Beach, FL; March 2001 – 0 fatalities, no hull loss, significant damage to wing control surfaces – NTSB findings: probable cause was loss-of-control due to increased stall speeds while operating in icing conditions (8K feet altitude loss prior to recovery) • Bombardier DHC-8-400: Clarence Center, NY; February 2009 – 50 fatalities, hull loss – NTSB findings: probable cause was captain’s inappropriate response to icing condition 5 Glenn Research -

Frost Heave Due to Ice Lens Formation in Freezing Soils 1

Nordic Hydrolgy, 26, 1995, 125-146 No pd11 m,ty ix ~rproduredby .my proce\\ w~thoutcomplete leference Frost Heave due to Ice Lens Formation in Freezing Soils 1. Theory and Verification D. Sheng, K. Axelsson and S. Knutsson Department of Civil Engineering, Lulei University of Technology, Sweden A frost heave model which simulates formation of ice lenses is developed for saturated salt-free soils. Quasi-steady state heat and mass flow is considered. Special attention is paid to the transmitted zone, i.e. the frozen fringe. The permeability of the frozen fringe is assumed to vary exponentially as a function of temperature. The rates of water flow in the frozen fringe and in the unfrozen soil are assumed to be constant in space but vary with time. The pore water pres- sure in the frozen fringe is integrated from the Darcy law. The ice pressure in the frozen fringe is detcrmined by the generalized Clapeyron equation. A new ice lens is assumed to form in the liozen fringe when and where the effective stress approaches zero. The neutral stress is determined as a simple function of the un- frozen water content and porosity. The model is implemented on an personal computer. The simulated heave amounts and heaving rates are compared with expcrimental data, which shows that the model generally gives reasonable esti- mation. Introduction The phenomenon of frost heave has been studied both experimentally and theoreti- cally for decades. Experimental observations suggest that frost heave is caused by ice lensing associated with thermally-induced water migration. Water migration can take place at temperatures below the freezing point, by flowing via the unfrozen wa- ter film adsorbed around soil particles. -

Permafrost Soils and Carbon Cycling

SOIL, 1, 147–171, 2015 www.soil-journal.net/1/147/2015/ doi:10.5194/soil-1-147-2015 SOIL © Author(s) 2015. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Permafrost soils and carbon cycling C. L. Ping1, J. D. Jastrow2, M. T. Jorgenson3, G. J. Michaelson1, and Y. L. Shur4 1Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station, Palmer Research Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks, 1509 South Georgeson Road, Palmer, AK 99645, USA 2Biosciences Division, Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, IL 60439, USA 3Alaska Ecoscience, Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA 4Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA Correspondence to: C. L. Ping ([email protected]) Received: 4 October 2014 – Published in SOIL Discuss.: 30 October 2014 Revised: – – Accepted: 24 December 2014 – Published: 5 February 2015 Abstract. Knowledge of soils in the permafrost region has advanced immensely in recent decades, despite the remoteness and inaccessibility of most of the region and the sampling limitations posed by the severe environ- ment. These efforts significantly increased estimates of the amount of organic carbon stored in permafrost-region soils and improved understanding of how pedogenic processes unique to permafrost environments built enor- mous organic carbon stocks during the Quaternary. This knowledge has also called attention to the importance of permafrost-affected soils to the global carbon cycle and the potential vulnerability of the region’s soil or- ganic carbon (SOC) stocks to changing climatic conditions. In this review, we briefly introduce the permafrost characteristics, ice structures, and cryopedogenic processes that shape the development of permafrost-affected soils, and discuss their effects on soil structures and on organic matter distributions within the soil profile. -

Ice Segregation As an Origin for Lenses of Non-Glacial Ice in "Ice-Cemented" Rock Glaciers

Journal of Glaciology, VoI. 27, No. 97, .g8. ICE SEGREGATION AS AN ORIGIN FOR LENSES OF NON-GLACIAL ICE IN "ICE-CEMENTED" ROCK GLACIERS By WILLIAM J. WAYNE (Department of Geology, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska 68588, D.S.A.) 0 ABSTRACT. In order to flow with the gradients observed (100 to 15 ) rock glaciers cannot be simply ice-cemented rock debris, but probably contain masses or lenses of debris-free ice. The nature and origin of the ice in rock glaciers that are in no way connected to ice glaciers has not been adequately explained. Rock glaciers and tal us above them are permeable. Water from snow-melt and rain flows through the lower part of the debris on top of the bedrock floor. In the headward part of a rock glacier, where the total thick ness is not great, if this groundwater flow is able to maintain water pressure against the base of an aggrading permafrost, segregation of ice lenses should take place. Ice segregation on a large scale would produce lenses of clear ice of sufficient size to permit the streams or lobes of rock debris to flow with gradients comparable to those of glaciers. It would also account for the substantial loss in volume that takes place when a rock glacier stabilizes and collapses. RESUME. La segregation de la glace a l'origine des lentilles de glace d'origine non glaciaire dans les glaciers rocheux soudis par la glace. Pour qu'ils puissent s'ecouler sur les pentes ou on les observe (100 a 150), les glaciers rocheux ne peuvent pas etre simplement constitues de debris rocheux soudes par la glace, mais contient probablement des blocs ou des lentilles de glace depourvus de sediments. -

High-Throughput Sequencing of Fungal Communities Across the Perennial Ice Block of Scărisoara̦ Ice Cave

Annals of Glaciology 59(77) 2018 doi: 10.1017/aog.2019.6 134 © The Author(s) 2019. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the same Creative Commons licence is included and the original work is properly cited. The written permission of Cambridge University Press must be obtained for commercial re-use. High-throughput sequencing of fungal communities across the perennial ice block of Scărisoara̦ Ice Cave Antonio MONDINI,1 Johanna DONHAUSER,2 Corina ITCUS,1 Constantin MARIN,3 Aurel PERȘOIU,1,4,5 Paris LAVIN,6,7 Beat FREY,2 Cristina PURCAREA1 1Department of Microbiology, Institute of Biology, Bucharest, Romania E-mail: [email protected] 2Swiss Federal Research Institute WSL, Birmensdorf, Switzerland 3Emil Racovita Institute of Speleology, Bucharest, Romania 4Stable Isotope Laboratory, Ștefan cel Mare University, Suceava, Romania 5Emil Racovită̦Institute of Speleology, Cluj-Napoca, Romania 6Laboratorio de Complejidad Microbiana y Ecología Funcional, Instituto Antofagasta, Universidad de Antofagasta, Antofagasta, Chile 7Departamento de Biotecnología, Facultad de Ciencias del Mar y Recursos Biológicos, Universidad de Antofagasta, Antofagasta, Chile ABSTRACT. This survey presents the first high-throughput characterisation of fungal distribution based on ITS2 Illumina sequencing of uncultured microbiome from a 1500 years old perennial ice deposit in Scărisoara̦ Ice Cave, Romania. Of the total of 1 751 957 ITS2 sequences, 64% corresponded to 182 fungal operational taxonomic units, showing a low diversity, particularly in older ice strata, and a distinct temporal distribution pattern. -

Preventing Ice Dams

{Property} Preventing Ice Dams waterWhat CAU Recommends: Introduction > Clean rain gutters annually to Ice dams represent a costly (and potentially remove obstructions that can dangerous) hazard for property owners and block the flow of water from community associations. Even worse, once a the roof building has shown itself to be susceptible to ice > Inspect attic insulation and dams, it is more likely to keep developing them ventilation during future cold weather. > Install ice shields or other waterproof membranes The majority of ice dams form as a ridge of ice beneath the roof covering along a rain gutter and roof eave. As ice builds during roof replacement up, it creates an unintended dam that prevents projects melting snow from draining off of the roof. Some > Locate a contractor that can can be very easy to see, but others form around clear ice dams from your skylights, chimneys, and other features that make buildings them harder to detect from the ground. Need More Information? Whether they are visible or not, ice dams can Additional information relating cause significant damage to a building or unit. to ice dam prevention is That’s because water that pools up behind it can available from The Institute find its way under the roof and into the structure for Business and Home Safety and the interior of a home. It isn’t unusual for (www.disastersafety.org) or by ice dams to cause damage to insulation, wall contacting CAU’s Loss Control interiors, ceiling finishes, and trim. Exterior Department. damage to roofs, gutters, and spaces below an ice dam (like windows and landscaping) is also common. -

Water Rescue Ice Rescue Training

Ice Rescue Know the Ice Ice Formation: Cold air cools surface of the water. As the surface water cools it becomes more dense and sinks—being replaced by the less dense and warmer water. This thermal inversion continues until the water is a consistent 39 degrees. At this point the water no longer becomes dense as it gets colder. The cold air continues to cool the water surface until the temperature is sufficient to create ice. Ice expands 9% as it is converted from water. It is therefore less dense and floats. Types of Ice: • Frazil - thin layers of new ice in disc shapes—very weak. • Clear Ice - New, Strong Ice • Snow Ice - Formed from refrozen snow, murky, porous--weak • Layer Ice - Layers of snow and other forms of ice, refrozen—weak • Anchor Ice - Form on very cold river bottoms and then releases with the warmth of the sun. • Pack Ice - Broken pieces of Ice, blown together and frozen in place. Will have holes and weak spots. Ice Strength: Thickness is only one factor in judging the strength of Ice. The formula for calculating the strength of Clear Ice is: Strength = 50 x thickness squared. (S = 50Tsq.) or 2" will support 200 lbs, 4" will support 800 lbs. Remember that Ice will be thickest near to shore. If you measure 3" at shore, count on losing at least an inch of ice as you move to deeper water. Other factors affecting ice: • Snow on Ice - can insulate Ice from the cold air. Warmer water below the ice may help it deteriorate. -

Cryolithogenesis Ground Ice Content of Frost Mounds In

EARTH’S CRYOSPHERE SCIENTIFIC JOURNAL Kriosfera Zemli, 2019, vol. XXIII, No. 2, pp. 25–32 http://www.izdatgeo.ru CRYOLITHOGENESIS DOI: 10.21782/EC2541-9994-2019-2(25-32) GROUND ICE CONTENT OF FROST MOUNDS IN THE NADYM RIVER BASIN N.M. Berdnikov1, A.G. Gravis1, D.S. Drozdov1–4, O.E. Ponomareva1,2, N.G. Moskalenko1, Yu.N. Bochkarev1,5 1 Earth Cryosphere Institute, Tyumen Scientifi c Centre SB RAS, P/O box 1230, Tyumen, 625000, Russia; [email protected] 2 Russian State Geological Prospecting University (MGRI–RSGPU), 23, Miklukho-Maclay str., Moscow, 117997, Russia 3 Tyumen State Oil and Gas University, 56, Volodarskogo str., Tyumen, 625000, Russia 4 Тyumen State University, 6, Volodarskogo str., Tyumen, 625003, Russia 5 Lomonosov Moscow State University, Faculty of Geography, 1, Leninskie Gory, Moscow, 119991, Russia The “classical type” ice-cored frost mounds (palsas) are widespread in the northern taiga of Western Si- beria. Besides, morphologically diff erent forms of permafrost hummocky landforms are developed, diff erentiat- ing from the “classical” frost mounds by size and fl atter top surface. Using core samples from ten-meter deep boreholes, we have analyzed the total thickness of segregated ice and the contribution of ice inclusions to the total soil ice content, to determine the origin of such fl at-topped mounds. A good correlation has been revealed between surface elevations and volumetric ice content of sediments composing fl at-topped peat mounds, whose ice content is found to be higher than in the intermound depressions. These facts indicate the local nature of ice segregation and therefore suggest that the investigated landforms were formed by the frost heave processes, rather than being remnant permafrost landforms. -

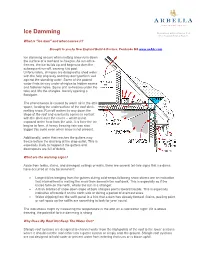

Ice Damming Reproduced with Permission from New England Build & Restore

Ice Damming Reproduced with permission from New England Build & Restore. What is "ice dam" and what causes it? Brought to you by New England Build & Restore, Pembroke MA www.neAbr.com Ice damming occurs when melting snow runs down the surface of a roof and re-freezes. As run-off re- freezes, the ice builds up and begins to dam the subsequent run-off, causing it to pool. Unfortunately, shingles are designed to shed water with the help of gravity and they don’t perform well against the standing water. Some of the pooled water finds its way under shingles to hidden seams and fastener holes. Some of it re-freezes under the tabs and lifts the shingles, literally opening a floodgate. The phenomenon is caused by warm air in the attic space, heating the undersurface of the roof deck, melting snow. Run-off makes its way down the slope of the roof and eventually comes in contact with the deck over the eaves -- which is not exposed to the heat from the attic. It is here the ice begins to form. A heavy freezing rain can also trigger this cycle even when snow is not present. Additionally, water that reaches the gutters may freeze before the draining at the drop outlet. This is especially likely to happen if the gutters and downspouts are full of debris. What are the warning signs? Aside from leaks, stains, and damaged ceilings or walls, there are several tell-tale signs that ice dams have occurred or may be imminent: • Large icicles hanging from the gutters during cold-snaps following snow storms are an indication that internal heat is melting the snow from beneath the roof deck.