Stopping for Death: Plays, Poetry, and Prose

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Administrative Services

Administrative Services Administrative Services covers a broad scope of responsibilities around campus. We do more than the financial function on campus. We are very collaborative with every department on campus, as well as many off-campus stakeholders. Our needs may overlap with each other, but our roles cover specific services to work with our students, staff, visitors or patrons; our customers. We view customer service as a consistent attribute between all our areas. Our departments are very collaborative throughout campus, working with almost every campus unit. The departments represented in Administrative Services include the Vice President for Administrative Services, Business Office, Facilities Management, Food Service, NIACC BookZone and our Copy Center. All of these departments interact with many other departments to provide service to our customers or stakeholders. People who see our campus or purchase tickets to or attended a Performing Arts and Leadership event have had an interaction with Administrative Services. What We Do The office of the Vice President for Administrative Services serves as the College budget manager and advisor to the College President. I provide assistance in preparing the budget for the institution, providing support and tools to individual budget managers to monitor the progress during the year, and advise the President of the College of budgetary, institutional, facility and financing issues or concerns. I serve as the Secretary to the Board, handle the banking for the College and coordinate the efforts between the stated various departments. I serve as Secretary/Treasurer for the NIACC Foundation. Insurances services for the college are coordinated through this office as well as banking and audit services. -

Volume 8 Issue 8 August 2013 MA GU WAM; Infrastructure and Economic Development

Isleta Pueblo News Volume 8 Issue 8 August 2013 MA GU WAM; Infrastructure and Economic Development. The Indian Pueblo Cultural Center in Tribal recommendations were made in Albuquerque also was launched by the 19 Greetings from each of the areas of concern to Governor New Mexico pueblos in 1976, “to showcase Governor Eddie Paul Torres: Martinez and the Departments on how we the history and accomplishments of the I hope that this News Letter finds all of can work together. It was the consensus of pueblo people from pre-Columbian to you in good health. This month has been the tribal leaders that this year's summit current time.” It features a 10,000-square- very busy for the Administration and was more productive than the last two foot museum. Program Services. First of all, on behalf of State Summits as it involved more dialogue A posting on the council’s Facebook page the Administration, I extend our sincere and networking. Thursday morning, which was quickly condolences to the families of the loved removed, said, “It’s a sad day in Pueblo ones that have passed away recently, our All Indian Pueblo Council drops Country, as of today the All Indian Pueblo prayers are with you. nonprofit business status Council is no longer!! 400+ years of tribal 2013 New Mexico State and Tribal By Staci Matlock: The New Mexican / leadership has been dissolved by the current Leaders Summit, Mescalero NM. Posted: Thursday, July 18, 2013 7:30 pm. leadership...” the council’s Facebook page Copyright © 2012 The New Mexican, was not available later in the day. -

00001. Rugby Pass Live 1 00002. Rugby Pass Live 2 00003

00001. RUGBY PASS LIVE 1 00002. RUGBY PASS LIVE 2 00003. RUGBY PASS LIVE 3 00004. RUGBY PASS LIVE 4 00005. RUGBY PASS LIVE 5 00006. RUGBY PASS LIVE 6 00007. RUGBY PASS LIVE 7 00008. RUGBY PASS LIVE 8 00009. RUGBY PASS LIVE 9 00010. RUGBY PASS LIVE 10 00011. NFL GAMEPASS 1 00012. NFL GAMEPASS 2 00013. NFL GAMEPASS 3 00014. NFL GAMEPASS 4 00015. NFL GAMEPASS 5 00016. NFL GAMEPASS 6 00017. NFL GAMEPASS 7 00018. NFL GAMEPASS 8 00019. NFL GAMEPASS 9 00020. NFL GAMEPASS 10 00021. NFL GAMEPASS 11 00022. NFL GAMEPASS 12 00023. NFL GAMEPASS 13 00024. NFL GAMEPASS 14 00025. NFL GAMEPASS 15 00026. NFL GAMEPASS 16 00027. 24 KITCHEN (PT) 00028. AFRO MUSIC (PT) 00029. AMC HD (PT) 00030. AXN HD (PT) 00031. AXN WHITE HD (PT) 00032. BBC ENTERTAINMENT (PT) 00033. BBC WORLD NEWS (PT) 00034. BLOOMBERG (PT) 00035. BTV 1 FHD (PT) 00036. BTV 1 HD (PT) 00037. CACA E PESCA (PT) 00038. CBS REALITY (PT) 00039. CINEMUNDO (PT) 00040. CM TV FHD (PT) 00041. DISCOVERY CHANNEL (PT) 00042. DISNEY JUNIOR (PT) 00043. E! ENTERTAINMENT(PT) 00044. EURONEWS (PT) 00045. EUROSPORT 1 (PT) 00046. EUROSPORT 2 (PT) 00047. FOX (PT) 00048. FOX COMEDY (PT) 00049. FOX CRIME (PT) 00050. FOX MOVIES (PT) 00051. GLOBO PORTUGAL (PT) 00052. GLOBO PREMIUM (PT) 00053. HISTORIA (PT) 00054. HOLLYWOOD (PT) 00055. MCM POP (PT) 00056. NATGEO WILD (PT) 00057. NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC HD (PT) 00058. NICKJR (PT) 00059. ODISSEIA (PT) 00060. PFC (PT) 00061. PORTO CANAL (PT) 00062. PT-TPAINTERNACIONAL (PT) 00063. RECORD NEWS (PT) 00064. -

PLC-Restart-Plan-2020-2021.Pdf

Pineland Learning Center RESTART AND RECOVERY PLAN FALL 2020 Ms. Mary Ellen Graham PLC Leadership Team 8/3/20 Executive Director 2 The Restart and Recovery Plan to Reopen Pineland Learning Center Fall 2020-2021 INTRODUCTION 13 The Six Key Principles 13 Principle 1: Demonstrate sustained reductions in new COVID-19 Cases & Hospitalizations 13 Principle 2: Expand testing capacity 13 Principle 3: Implement robust contact tracing 13 Principle 4: Secure safe places & resources for isolation and quarantine 14 Principle 5: Execute a responsible economic restart 14 Principle 6: Ensure New Jersey’s resiliency 14 Pineland Learning Center Demographics 15 Pineland Learning Center demographics table 15 Projected enrollment 16 The 2020-2021 Planning Design 16 Parent survey #1—student engagement 16 Staff survey #1—staff engagement 18 A. CONDITIONS FOR LEARNING 19 1. Health & Safety—Standards for Establishing Safe & Healthy Conditions for Learning 20 a. Critical area of operation #1—general health and safety guidelines 21 (1) COVID-19 actions 21 (a) Communication to determine current mitigation levels 21 (b) Supporting high-risk students and staff 22 (c) The CDC's Guidance for Schools and Childcare Programs 23 (d) Promoting behaviors that reduce the spread of COVID-19 24 (e) Accommodations for individuals having a higher risk for severe illness from COVID-19 25 b. Critical area of operation #2—classrooms, testing, and therapy rooms 26 (1) Social distancing in the classroom 26 (2) Face-coverings are required for students, visitors, & staff 27 (a) Face-coverings -

美國影集的字彙涵蓋量 語料庫分析 the Vocabulary Coverage in American

國立臺灣師範大學英語學系 碩 士 論 文 Master’s Thesis Department of English National Taiwan Normal University 美國影集的字彙涵蓋量 語料庫分析 The Vocabulary Coverage in American Television Programs A Corpus-Based Study 指導教授:陳 浩 然 Advisor: Dr. Hao-Jan Chen 研 究 生:周 揚 亭 Yang-Ting Chou 中 華 民 國一百零三年七月 July, 2014 國 立 英 臺 語 灣 師 學 範 系 大 學 103 碩 士 論 文 美 國 影 集 的 字 彙 涵 蓋 量 語 料 庫 分 析 周 揚 亭 中文摘要 身在英語被視為外國語文的環境中,英語學習者很難擁有豐富的目標語言環 境。電視影集因結合語言閱讀與聽力,對英語學習者來說是一種充滿動機的學習 資源,然而少有研究將電視影集視為道地的語言學習教材。許多研究指出媒體素 材有很大的潛力能激發字彙學習,研究者很好奇學習者要學習多少字彙量才能理 解電視影集的內容。 本研究探討理解道地的美國電視影集需要多少字彙涵蓋量 (vocabulary coverage)。研究主要目的為:(1)探討為理解 95%和 98%的美國影集,分別需要 英國國家語料庫彙編而成的字族表(the BNC word lists)和匯編英國國家語料庫 (BNC)與美國當代英語語料庫(COCA)的字族表多少的字彙量;(2)探討為理解 95%和 98%的美國影集,不同的電視影集類型需要的字彙量;(3)分析出現在美國 影集卻未列在字族表的字彙,並比較兩個字族表(the BNC word lists and the BNC/COCA word lists)的異同。 研究者蒐集六十部美國影集,包含 7,279 集,31,323,019 字,並運用 Range 分析理解美國影集需要分別兩個字族表的字彙量。透過語料庫的分析,本研究進 一步比較兩個字族表在美國影集字彙涵蓋量的異同。 研究結果顯示,加上專有名詞(proper nouns)和邊際詞彙(marginal words),英 國國家語料庫字族表需 2,000 至 7,000 字族(word family),以達到 95%的字彙涵 蓋量;至於英國國家語料庫加上美國當代英語語料庫則需 2,000 至 6,000 字族。 i 若須達到 98%的字彙涵蓋量,兩個字族表都需要 5,000 以上的字族。 第二,有研究表示,適當的文本理解需要 95%的字彙涵蓋量 (Laufer, 1989; Rodgers & Webb, 2011; Webb, 2010a, 2010b, 2010c; Webb & Rodgers, 2010a, 2010b),為達 95%的字彙涵蓋量,本研究指出連續劇情類(serial drama)和連續超 自然劇情類(serial supernatural drama)需要的字彙量最少;程序類(procedurals)和連 續醫學劇情類(serial medical drama)最具有挑戰性,因為所需的字彙量最多;而情 境喜劇(sitcoms)所需的字彙量差異最大。 第三,美國影集內出現卻未列在字族表的字會大致上可分為四種:(1)專有 名詞;(2)邊際詞彙;(3)顯而易見的混合字(compounds);(4)縮寫。這兩個字族表 基本上包含完整的字彙,但是本研究顯示語言字彙不斷的更新,新的造字像是臉 書(Facebook)並沒有被列在字族表。 本研究也整理出兩個字族表在美國影集字彙涵蓋量的異同。為達 95%字彙涵 蓋量,英國國家語料庫的 4,000 字族加上專有名詞和邊際詞彙的知識才足夠;而 英國國家語料庫合併美國當代英語語料庫加上專有名詞和邊際詞彙的知識只需 3,000 字族即可達到 95%字彙涵蓋量。另外,為達 98%字彙涵蓋量,兩個語料庫 合併的字族表加上專有名詞和邊際詞彙的知識需要 10,000 字族;英國國家語料 庫字族表則無法提供足以理解 98%美國影集的字彙量。 本研究結果顯示,為了能夠適當的理解美國影集內容,3,000 字族加上專有 名詞和邊際詞彙的知識是必要的。字彙涵蓋量為理解美國影集的重要指標之一, ii 而且字彙涵蓋量能協助挑選適合學習者的教材,以達到更有效的電視影集語言教 學。 關鍵字:字彙涵蓋量、語料庫分析、第二語言字彙學習、美國電視影集 iii ABSTRACT In EFL context, learners of English are hardly exposed to ample language input. -

Man Stabbed in Walmart Parking Lot

READERS SUBMIT FIRST DAY OF GET YOUR BALLOT SCHOOL PHOTOS, A8-10 INSIDE! Sports editor says California law hits new level of insanity, B1 TheTThehe AndersonAAndersonnderson NewsNNewsews Setting standards of excellence since 1877 Lawrenceburg, Kentucky Wednesday, August 21, 2013 75 cents Man stabbed in Walmart parking lot Sunday afternoon in the renceburg man Michael serious injuries, police said, Sunday afternoon when he 28-year-old man Walmart parking lot, several Aaron Joseph, 28, 1777 Bypass and as of Monday afternoon, saw Joseph, who had been witnesses told South, for first degree assault Washington was recuperat- shopping with his wife at arrested, charged with city police. after he stabbed Cedric ing from surgery in the hos- Walmart. Then one of Washington, 29, of Lawrence- pital. The two men started talk- first degree assault the men yelled burg once in the stomach According to Lt. Mike ing in the parking lot, not too By Meaghan Downs that he’d been with a small hunting knife Schell of the Lawrenceburg far away from the grocery News staff stabbed and to in the Walmart parking lot. police department, Wash- entrance of the store. call 911. Washington was trans- ington said he had finished Washington’s girlfriend The two men looked like City police ported to the University of eating at Subway with his buddies catching up on a arrested Law- Joseph Kentucky medical center for girlfriend around 4:30 p.m. See ASSAULT, Page A2 WELCOME BACK, ANDERSON COUNTY STUDENTS! Man saves grandson, gets run over by tractor Best airlifted for serious injuries in accident on Wooldridge Spur By Meaghan Downs News staff A Lawrenceburg man pushed his two-year-old grandson out of the way before being run over by a trac- tor on Wooldridge Spur last Friday evening. -

PUC Approves Golden State Water's Tiered Rate Plan

Serving the Community of Orcutt, California • September 23, 2009 • www.OrcuttPioneer.com • Circulation 17,000 + PUC Approves Golden State Water’s Tiered Rate Plan Some changes are under way at proportion of Golden State’s fixed that all of the proposed changes were usage customers toward reduced Golden State Water, the company costs will be recovered based on the reasonable, consistent with law, and usage and provide incentive to stay that provides water for many Orcutt water consumed.” in the public interest, which resulted within the second tier, according to area homes. A.08-09-010The ALJ/GW2/jycdocument goes on to explain in approval. Golden State. The Public Utilities Commission that “water sales and revenue col- The new three-tier system is part of However, according to opponent of the State of California authorized lection will be decoupled throughTABLE a 1three13 year Pilot Program and will Gerald Trimble at OrcuttWater.com, Golden State to “implement a rateA.08-09-010 a water ALJ/GW2/jyc revenue adjustmentPROPOSED mecha- RESIDENTIALinvolve RATES extensive FOR regular reports to some calculations show that cus- BAY POINT, LOS OSOS, SANTA MARIA & SIMI VALLEY design that will establish different nism and a modified cost balancing the Commission. The purpose of the tomers may be billed less, but that rates based on levels of consumptionRATEMAKING account.”CURRENT PROPOSED The CommissionCURRENT foundPROPOSED three-tier13 QUANTITY RATEstructure is to shiftAVERAGE higher CONSUMPTION additional charges may show up on AREA SERVICE SERVICE QUANTITY TABLE 1 ANNUAL AT WHICH in order to promote con- (METER) (METER) RATE TIER I TIER II TIER III CONSUMPTION NEW BILL later bills for unused water. -

August - September 2015

Kenny Loosvelt Volume 10 YMS PRINCIPAL Number 1 Be Safe, Be Respectful, Be Responsible August - September 2015 Middle Years—Each month I provide a publication called, ‘The Middle Years.’ This publication is jammed packed with tips and information that will aid parents and students in their trek through middle school. The publication will be found inside every newsletter and we hope you enjoy the information. What can I control? York Public Schools Mission Statement These three short years at YMS are full of changes for students both York Public Schools will prepare each learner physically, emotionally, socially as well as academically. Two constants with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary that everyone can control is your Attitude & Effort. I want all students to become an effective citizen by providing to come to school each day knowing that if they choose a positive atti- diversified curriculum and experiences. tude and give a great effort, they will have had a successful day. Parents thank you for encouraging your middle school child to chose a great Attitude & Effort each day! Hello York Middle School Parents and Students. I am extremely excited to be the new principal at YMS. This is my 17th year in Be Safe, Be Respectful, Be Responsible— YMS behavior expecta- education. I taught life science at Madison High School for 14 tions are based upon the 3 B’s. Doing this will allow all students to grow years before taking the responsibilities of the PreK-5 grade academically, physically, emotionally and socially. Throughout the year principal, also at Madison. I feel working with students at the students will be taught what it looks like to be safe, respectful, and re- high school level and at the elementary level makes me a great sponsible at school and also throughout their daily lives. -

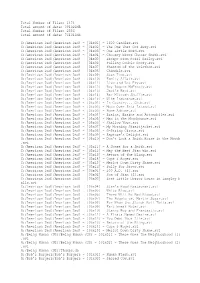

2556 Total Amount of Data: 761041MB G:/America

Total Number of Files: 1474 Total amount of data: 391021MB Total Number of Files: 2556 Total amount of data: 761041MB G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x01] - 1600 Candles.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x02] - The One That Got Away.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x03] - One Little Word.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x04] - Choosey Wives Choose Smith.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x05] - Escape From Pearl Bailey.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x06] - Pulling Double Booty.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x07] - Phantom of the Telethon.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x08] - Chimdale.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x09] - Stan Time.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x10] - Family Affair.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x11] - Live and Let Fry.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x12] - Roy Rogers McFreely.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x13] - Jack's Back.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x14] - Bar Mitzvah Shuffle.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [04x15] - Wife Insurance.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [05x01] - In Country... Club.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [05x02] - Moon Over Isla Island.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [05x03] - Home Adrone.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [05x04] - Brains, Brains and Automobiles.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [05x05] - Man in the Moonbounce.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [05x06] - Shallow Vows.avi G:/American Dad!/American Dad! - [05x07] - My Morning Straitjacket.avi G:/American -

Watch All Seasons of Scrubs Online Free

Watch all seasons of scrubs online free click here to download Scrubs - Season 1 Scrubs is a comedy which takes place in the unreal world of Sacred Heart Hospital. It has content tells about John J.D Dorian, who learns the. Watch Scrubs: Season 1 Online | scrubs: season 1 | Scrubs Season 1 () | Director: | Cast: Zach. Scrubs. 9 Seasons available with subscription. Start Your Free Trial. Season 1 24 Episodes. Season 2 22 Episodes. Season 3 22 Episodes. Season 4 On this website you can watch all Scrubs series episodes online and for free. "Scrubs" is an American medical comedy-drama television series created by Bill. Watch Scrubs Online: Watch full length episodes, video clips, highlights and more. Scrubs Online. Watch Scrubs now on Hulu logo. kill All Free (0); All Paid. In the unreal world of Sacred Heart Hospital, intern John 'J.D' Dorian learns the ways of medicine, friendship and life., streaming, watch online. «Scrubs» – Season 1, Episode 2 watch in HD quality with subtitles in different languages for free and without registration! Buy Scrubs Season 1: Read Movies & TV Reviews - www.doorway.ru Scrubs 9 Seasons .. Format, Amazon Video (streaming online video). Watch Scrubs Saison 1 Online, In the unreal world of Sacred Heart Hospital, intern Episode Season 1, Episode 24 - My Last Day Episode Season 1. Scrubs Season 1 Online All Episodes free to Watch. Watch scrubs season 1 here: www.doorway.ru?p=12 watch complete season. Watch Scrubs - Season 1 YIFY Movies Online. Scrubs is a comedy which takes place in the unreal world of Sacred Heart Hospital.