Metropolitan Latino Political Behavior: Voter Turnout and Candidate Preference in Los Angeles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPDATED KPCC-KVLA-KUOR Quarterly Report JAN-MAR 2013

Date Key Synopsis Guest/Reporter Duration Quarterly Programming Report JAN-MAR 2013 KPCC / KVLA / KUOR 1/1/13 MIL With 195,000 soldiers, the Afghan army is bigger than ever. But it's also unstable. Rod Nordland 8:16 When are animals like humans? More often than you think, at least according to a new movement that links human and animal behaviors. KPCC's Stephanie O'Neill 1/1/13 HEAL reports. Stephanie O'Neill 4:08 We've all heard warning like, "Don't go swimming for an hour after you eat!" "Never run with scissors," and "Chew on your pencil and you'll get lead poisoning," from our 1/1/13 ART parents and teachers. Ken Jennings 7:04 In "The Fine Print," Pulitzer Prize-winning author David Cay Johnston details how the David Cay 1/1/13 ECON U.S. tax system distorts competition and favors corporations and the wealthy. Johnston 16:29 Eddie Izzard joins the show to talk about his series at the Steve Allen Theater, plus 1/1/13 ART he fills us in about his new show, "Force Majeure." Eddie Izzard 19:23 Our regular music critics Drew Tewksbury, Steve Hochman and Josh Kun join Alex Drew Tewksbury, Cohen and A Martinez for a special hour of music to help you get over your New Steve Hochman 1/1/13 ART Year’s Eve hangover. and Josh Kun 12:57 1/1/2013 IMM DREAM students in California get financial aid for state higher ed Guidi 1:11 1/1/2013 ECON After 53 years, Junior's Deli in Westwood has closed its doors Bergman 3:07 1/1/2013 ECON Some unemployed workers are starting off the New Year with more debt Lee 2:36 1/1/2013 ECON Lacter on 2013 predictions -

Governing Urban School Districts: Efforts in Los Angeles to Effect

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION Jump down to document ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT 6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Education View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. This product is part of the RAND Corporation technical report series. Reports may include research findings on a specific topic that is limited in scope; present discus- sions of the methodology employed in research; provide literature reviews, survey instruments, modeling exercises, guidelines for practitioners and research profes- sionals, and supporting documentation; or deliver preliminary findings. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure that they meet high standards for re- search quality and objectivity. Governing Urban School Districts Efforts in Los Angeles to Effect Change Catherine H. Augustine, Diana Epstein, Mirka Vuollo The research described in this report was conducted within RAND Education for the Presidents' Joint Commission on LAUSD Governance. -

2016 Forecast LA Conference Book

Forecast LA StudyLA 2016 2016 Forecast LA Conference Book Fernando J. Guerra et al Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/forecastla Recommended Citation Guerra, Fernando J. et al, "2016 Forecast LA Conference Book" (2016). Forecast LA. 3. https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/forecastla/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the StudyLA at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Forecast LA by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOYOLA MARYMOUNT UNIVERSITY | 2016 PREPARING FOR THE FUTURE OF THE REGION Forecast LA would like to thank the following companies and organizations for their support. THOMAS SAFRAN & ASSOCIATES PREPARING FOR THE FUTURE OF THE REGION Forecast LA Program Wednesday, April 20, 2016 | Gersten Pavilion Breakfast Welcome Timothy Law Snyder, President, Loyola Marymount University Opening Remarks Ron Galperin, Controller, City of Los Angeles Los Angeles Public Opinion Survey Fernando J. Guerra, Director, Center for the Study of Los Angeles, Loyola Marymount University Leaders Survey: Public School Superintendents of Los Angeles County Shane P. Martin, Dean, School of Education, Loyola Marymount University National, State & Regional Economic Forecast Chris Thornberg, Founding Partner, Beacon Economics Audience Q&A Closing Remarks Introduction Dean Logan, Registrar-Recorder/County Clerk, Los Angeles County Closing Remarks Alex Padilla, Secretary of State, State of California For more information: Thomas and Dorothy Leavey Center for the Study of Los Angeles Loyola Marymount University 1 LMU Drive, Suite 4119, Los Angeles, CA 90045 310.338.4565 [email protected] Contents ABOUT US & AUTHORS ....................................... -

Communication from Public

Communication from Public Name: Brentwood Community Council Statement on 20-0692 Date Submitted: 06/21/2020 08:46 PM Council File No: 20-0692 Comments for Public Posting: BCC Response to Motion as Currently Drafted by Council President Nury Martinez, Councilmembers Wesson, Price (Council File 20-06092 The Brentwood Community Council ["BCC"] recognizes that people of color, particularly African Americans, frequently suffer needless levels of harm and loss of life during interactions with police departments around the United States, including Southern California. The BCC also recognizes that sworn LAPD officers have been expected to perform duties that may be better addressed by trained civilians or medical and mental health professionals. However, the BCC opposes the Council motion as it proposes an arbitrary reduction to the LAPD budget without describing specific steps the City will take to address the underlying societal issues it identifies, nor does it require an audit or other management improvements of the multiple City and County agencies involved in overall community safety, nor does it include wide community input, particularly since any change to the LAPD impacts all residents. Therefore, in the spirit of the City Council’s call to address societal repair and change, we recommend the following: •The City of Los Angeles first adopt a budget process that incorporates all potential sources of revenue and support for community safety and health, inside and outside the LAPD—to include, for example, the Prop HHH $1B in housing bonds, -

Here We Are, Learn Best Practices from Experienced Practitioners, Learn New Teaching Techniques and Strengthen Our National Network

JUNE 26–30, 2017 ARTS IN CORRECTIONS BUILDING BRIDGES to the FUTURE Table of Contents Program 1 Speakers/Presenters Biographies 13 Sequential Master Artist Classes Course Catalogue 27 Selected Session Notes 54 Final Report 65 Conference Photos 70 Thank you to our conference photographers. Peter Merts Arts in Corrections Photo Gallery Brian C. Moss Arts in Corrections Photo Gallery California Lawyers for the Arts and the William James Association In collaboration with Loyola Marymount University Present a National Conference Arts in Corrections: Building Bridges to the Future June 26 to 30, 2017 Loyola Marymount University Los Angeles, California This conference will provide expert practitioners in the field of arts in corrections with opportunities to showcase best practices, learn about current research models and results, and gain insights into new developments and challenges. The intended audience includes experienced artists as well as those who are new to arts in corrections. All participants will have opportunities to take sequential classes from master artists with years of experience teaching art of different disciplines in institutional settings. In addition to artists and arts administrators, speakers will include educators, lawyers, and other allied professionals. Desired Outcomes To celebrate and inspire creativity To share experience and expand knowledge To invite and encourage newcomers to the field To dialogue and cross-fertilize To build a network for mutual support Acknowledgements National Endowment for the Arts California -

Annual Report 2013 Mission Statement

LOS ANGELES POLICE DEPARTMENT ANNUAL REPORT 2013 MISSION STATEMENT It is the mission of the Los Angeles Police Depart- ment to safeguard the lives and property of the people we serve, to reduce the incidence and fear of crime, and to enhance public safety while working with the diverse communities to improve their quality of life. Our mandate is to do so with honor and integrity, while at all times conducting ourselves with the highest ethical standards to maintain public confidence. LOS ANGELES POLICE DEPARTMENT L e a d e r s h i p As 2013 draws to a close, I would like to take this opportunity to say Thank You to the men and women of the Los Angeles Police Department. Your hard work and dedication has us on pace to achieve an eleventh straight year of crime reduction in the City of Los Angeles. This is a tremendous achievement. The people of our great City are the safest they have been in decades and that is thanks in no small part to you. Your professionalism and commitment to constitutional policing throughout the year have made all the difference. Thank you for a job well done! Excerpt from Chief’s December 2013 message Police Commission The Board of Police Commissioners sets policies for the Los Angeles Police Department and oversees its operations. Commissioners are appointed by the Mayor and approved by the Los Angeles City Council. "We're going to keep up the momentum on crime to make every L.A. neighborhood safer and more prosperous," Mayor Garcetti said. -

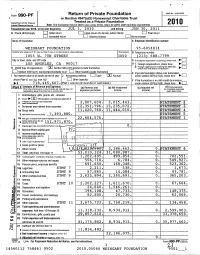

Form 990-PF Or Section 4947(A)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust ^O^ O

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust ^O^ O Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements For calendar year 2010 , or tax year beginning JUL 1, 2010 , and ending JUN 30, 2011 G Check all that apply initial return Initial return of a former public charity Final return Amended return 0 Address change Name change Name of foundation A Employer identification number WEINGART FOUNDATION 95-6054814 Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number 1055 W. 7TH STREET 13050 ( 213 ) 688-7799 El City or town , state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending , check here ► LOS ANGELES, CA 90017 D 1 • Foreign organizations , check here 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, H Check type of org anization X Section 501 ()()c 3 exempt private foundation check here and attach computation Section 4947 ) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable rivate foundation (a )( 1 0 p E If private foundation status was terminated LX I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method 0 Cash Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ► (from Part ll, col. (c), line 16) = Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination (Part 1, column (o( must be on cash basis.) ► $ 718,445,607 . under section 507 ( b)( 1 ) B , check here ► Part I Analysis of Revenue and Expenses ( Revenue and (b ) Net investment (c) Adjusted net ( d ) Disburs ements (The total of amounts in columns (c), and (d) may not for charitable purposes necessarily equal the amounts in column (a)) ex pensesPenses per books income income (cash basis only) 1 Contributions , gifts, grants , etc , received 2 Check [RI] It the foundation issnot required to attach Sch B ____________________________ _____________________________ Interest and temporary 3 nvestmentss 3,007,604. -

Joel Wachs Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c82r3sdr No online items Joel Wachs Papers Clay Stalls William H. Hannon Library Loyola Marymount University One LMU Drive, MS 8200 Los Angeles, CA 90045-8200 Phone: (310) 338-5710 Fax: (310) 338-5895 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.lmu.edu © 2013 Loyola Marymount University. All rights reserved. Joel Wachs Papers CSLA-29 1 Joel Wachs Papers Collection number: CSLA-29 William H. Hannon Library Loyola Marymount University Los Angeles, California Processed by: Clay Stalls Date Completed: 2006 Encoded by: Clay Stalls © 2013 Loyola Marymount University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Joel Wachs papers Dates: 1951-2002 Bulk Dates: 1969-2002 Collection number: CSLA-29 Creator: Wachs, Joel Collection Size: 116 archival document boxes, 1 records storage box, 4 oversize boxes, 4 flat files Repository: Loyola Marymount University. Library. Department of Archives and Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90045-2659 Abstract: This collection contains constituent correspondence, mayoral and city council campaign records, and some personal papers of Joel Wachs, Los Angeles city councilman from 1971 until 2001. The holdings are especially valuable for understanding the critical mayoral campaigns in Los Angeles in 1993 and 2001, as well as issues of concern to the constituents of his city council district. These materials are not official city records; the official records of his city council tenure are located in the Los Angeles City Archives (213-473-8449). To learn more about the contents of this collection and their organization, consult the following sections of this on-line guide. Languages: Languages represented in the collection: English Access Collection is open to research under the terms of use of the Department of Archives and Special Collections, Loyola Marymount University. -

Here Was “Zero Evidence of Racial Profiling” and in Order to Examine Concerns Regarding Racial Profiling “Rigorous Investigation” Would Be Needed

1 Stop LAPD Spying Coalition February 24, 2015 Commissioner President Steve Soboroff Commissioner Vice President Paula Madison Commissioner Sandra Figueroa-Villa Commissioner Kathleen Kim Commissioner Robert M. Saltzman Los Angeles Board of Police Commissioners 100 West First Street, Suite 134 Los Angeles, California 90012 Dear Commissioners: On behalf of the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition (“coalition”) we write to you with deep concern on the failure of the Los Angeles Board of Police Commissioners (“commission”) to meaningfully respond to community concerns regarding the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD). The function and role of the Board of Police Commissioners officially states: “The Commissioners’ concerns are reflective of the community-at-large, and their priorities include implementing recommended reforms, improving service to the public by the Department, reducing crime and the fear of crime, and initiating, implementing and supporting community policing programs.”1 Yet on several occasions when communities across Los Angeles have brought to the commission’s attention LAPD programs, policies, and enforcement practices that continue to violate human and civil rights of residents of Los Angeles, the commission has repeatedly dismissed these concerns and failed to act upon communities’ requests to investigate and take corrective action. Following are some of the recent examples of the commission’s failure to act upon Los Angeles communities’ concerns: Racial Profiling On January 27, 2015 the Office of Inspector General (OIG) released the audit of LAPD Suspicious Activity Reporting (SAR) program for the fiscal year 2013-2014.2 The audit revealed disproportionately high numbers of SARs filed on Los Angeles’ Black communities – 30% of total SARs sent to Fusion centers were on blacks while the city’s black population is just under 10%. -

Chamber Recognizes Urban Design Achievements

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Erin Kettle, (310) 226-3063 October 12, 2004 [email protected] CHAMBER RECOGNIZES URBAN DESIGN ACHIEVEMENTS 69th Annual Construction Industry Awards recognize impact of individuals on LA’s built environment Los Angeles, CA – The Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce presents the 69th Annual Construction Industry Awards today, honoring renowned individuals for their contributions to the Los Angeles cityscape. Ray Kappe, Steve Soboroff and the late Paul Williams were presented with Lifetime Achievement Awards, and the LAUSD Facilities Services Division, led by Superintendent Roy Romer, received the Ira Yellin Distinguished Achievement Award at a luncheon at the Omni Los Angeles Hotel in Downtown LA. Ray Kappe is an internationally recognized and published architect-planner- educator who has been in the architectural practice for 50 years. While his work is considered to be an extension of the early Southern California master architects, he will also leave a lasting mark in the industry as the founder of the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-ARC). Thom Mayne, partner at Morphosis and architect of the new Caltrans headquarters in Downtown LA, presented Kappe with his award. Steve Soboroff is a real estate executive who has had a significant impact on the Los Angeles landscape. He is a past president of the Recreation and Parks Commission, served as a senior advisor to former Mayor Richard Riordan and spearheaded such projects as the Alameda Corridor and Staples Center. Currently, Soboroff serves as the president of Playa Vista, one of the nation’s most significant mixed-use real estate projects. Riordan, who currently serves as California Secretary for Education, was on hand to present the award to Soboroff. -

Annual Report 2005 2005 Annual Report 2005 Annual Report

Making a Difference...Helping Members Grow Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce Annual Report 2005 2005 Annual Report 2005 Annual Report Christopher C. Martin FAIA Russell J. “Rusty” Hammer Chief Executive Officer President & CEO AC Martin Partners Los Angeles Area 2005 Board Chair Chamber of Commerce To Our Members: The Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce responded to pressing issues in 2005 with a strong, unified front resulting in significant progress for our region’s business community. The L.A. region is one of the most vibrant places in the world to do business and to live. Each day we advocated for change— supporting initiatives for the education of our children and pushing to rebuild our infrastructure. Since its founding in 1888, the Chamber has been serving the needs of the Los Angeles business community through business development, public policy and advocacy initiative programs. More than a century later, the Chamber has been more active than ever in raising its voice on critical business and political issues on topics that matter the most to our members. This annual report highlights the Chamber’s activities in 2005, including programs that helped enhance members’ companies and Access advocacy trips to Washington, D.C., Sacramento and Los Angeles City Hall. Through our partnerships with other business organizations across the L.A. region, we created a powerful voice for businesses. Our Chamber leaders and committees led the way to great achievements in 2005. Sincerely, 1 2005 Annual Report Mission By being the voice of business, helping its members grow and promoting collaboration, the Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce seeks full prosperity for the Los Angeles region THE VOICE OF BUSINESS Advocacy & Public Policy Initiatives Major Public Policy Accomplishments Business advocacy at the local, state and federal level remained a focal point for the Chamber in 2005. -

Los Angeles Lawyer September 2015

CALIFORNIACORPORATE ATTORNEYS COUNSEL THE MAGAZINE OF THE LOS ANGELES COUNTY BAR ASSOCIATION GUIDE TO ’S SEPTEMBER 2015 / $4 EARN MCLE CREDIT PLUS Evidentiary LA Signage Objections Litigation page 25 page 30 New Paid Sick Leave Law page 14 When Trial Transcripts Are Needed page 10 Cyberinsurance Coverage Achieving page 37 Ability Los Angeles lawyer Thomas E. Beltran outlines the ABLE Act’s applications for public benefits recipients page 18 • Rigorous standards • Tailored service • Prompt turnaround • Free initial consultations • Free resume book • Reasonable rates L O C A L O F F I C E Pro/Consul Inc. 1945 Palo Verde Avenue, Suite 200 Long Beach, CA 90815-3443 (562) 799-0116 • Fax (562) 799-8821 Hours of Operation: 6 a.m. - 6 p.m. [email protected] • ExpertInfo.com FEATURES 18 Achieving Ability BY THOMAS E. BELTRAN ABLE accounts will soon allow the use of relatively small amounts of money to make periodic payments on behalf of eligible beneficiaries 25 Evidently Objectionable BY VIVIAN F. WANG A recent Judicial Council report recommends amending Section 437c of the Code of Civil Procedure to provide greater clarity for rulings on objections to evidence Plus: Earn MCLE credit. MCLE Test No. 249 appears on page 27. 30 Floors, Ceilings, and Signs BY JAMES S. AZADIAN AND ERIC G. SALBERT The Los Angeles Superior Court recently concluded that the Ninth Circuit could not dispense with the California Supreme Court’s Article 1 jurisprudence Special Pullout Section Corporate Counsel's Guide to California Law Firms and Attorneys Los Angeles Lawyer DEPARTME NTS the magazine of the Los Angeles County 8 On Direct 37 Computer Counselor Bar Association Steve Soboroff How courts have decided coverage issues September 2015 INTERVIEW BY DEBORAH KELLY in cyber insurance cases BY JIM VORHIS AND JOAN COTKIN Volume 38, No.