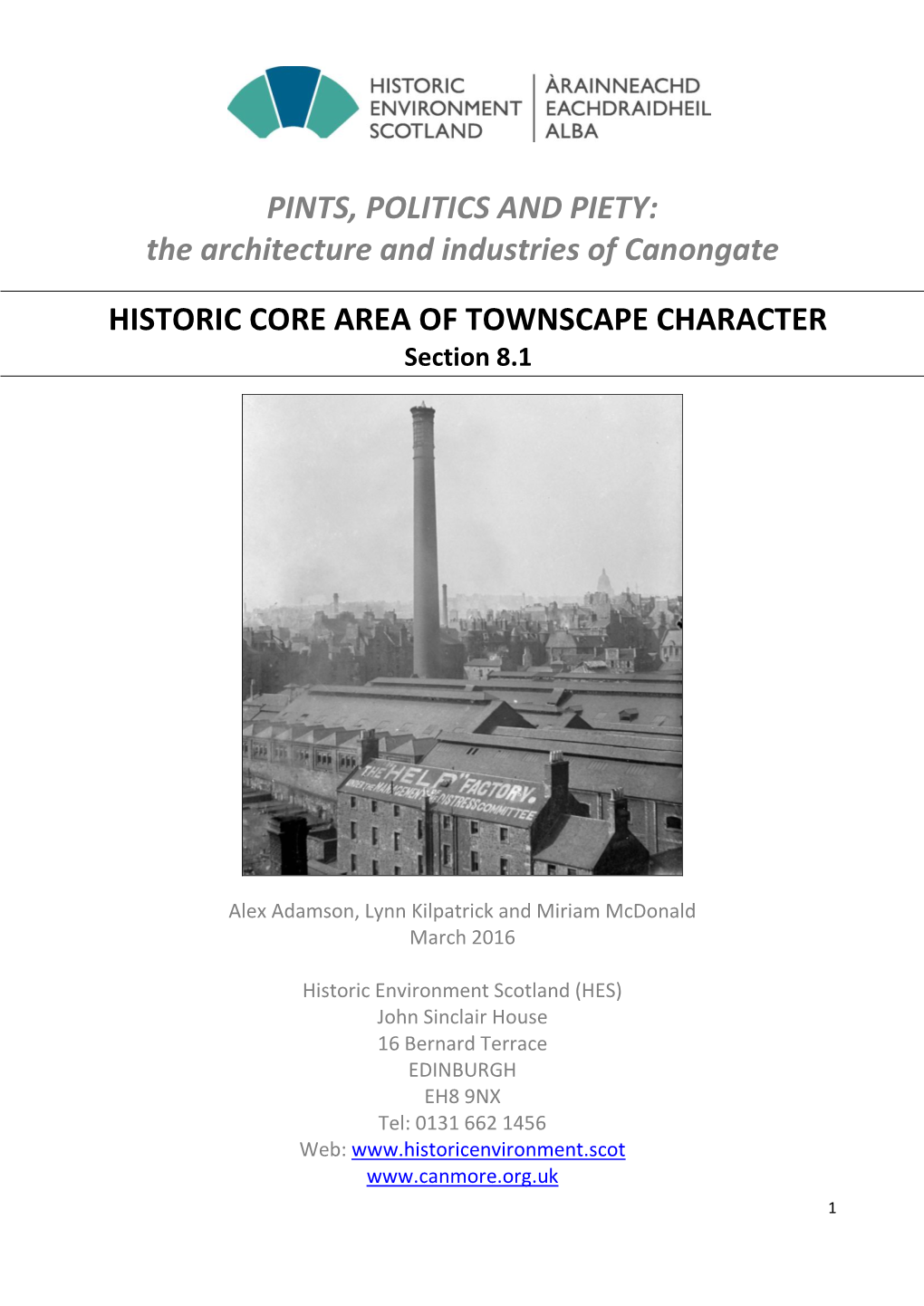

PINTS, POLITICS and PIETY: the Architecture and Industries of Canongate HISTORIC CORE AREA of TOWNSCAPE CHARACTER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Written Guide

The tale of a tail A self-guided walk along Edinburgh’s Royal Mile ww.discoverin w gbrita in.o the stories of our rg lands discovered th cape rough w s alks 2 Contents Introduction 4 Route map 5 Practical information 6 Commentary 8 Credits © The Royal Geographical Society with the Institute of British Geographers, London, 2015 Discovering Britain is a project of the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) The digital and print maps used for Discovering Britain are licensed to the RGS-IBG from Ordnance Survey Cover image: Detail from the Scottish Parliament Building © Rory Walsh RGS-IBG Discovering Britain 3 The tale of a tail Discover the stories along Edinburgh’s Royal Mile A 1647 map of The Royal Mile. Edinburgh Castle is on the left Courtesy of www.royal-mile.com Lined with cobbles and layered with history, Edinburgh’s ‘Royal Mile’ is one of Britain’s best-known streets. This famous stretch of Scotland’s capital also attracts visitors from around the world. This walk follows the Mile from historic Edinburgh Castle to the modern Scottish Parliament. The varied sights along the way reveal Edinburgh’s development from a dormant volcano into a modern city. Also uncover tales of kidnap and murder, a dramatic love story, and the dramatic deeds of kings, knights and spies. The walk was originally created in 2012. It was part of a series that explored how our towns and cities have been shaped for many centuries by some of the 206 participating nations in the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games. -

The Old and New Towns of Edinburgh World Heritage Site Management Plan

The Old and New Towns of Edinburgh World Heritage Site Management Plan July 2005 Prepared by Edinburgh World Heritage on behalf of the Scottish Ministers, the City of Edinburgh Council and the Minister for Media and Heritage Foreword en years on from achieving World Heritage Site status we are proud to present Edinburgh’s first World Heritage Site Management Plan. The Plan provides a framework T for conservation in the heart of Scotland’s capital city. The preparation of a plan to conserve this superb ‘world’ city is an important step on a journey which began when early settlers first colonised Castle Rock in the Bronze Age, at least 3,000 years ago. Over three millennia, the city of Edinburgh has been shaped by powerful historical forces: political conflict, economic hardship, the eighteenth century Enlightenment, Victorian civic pride and twentieth century advances in science and technology. Today we have a dynamic city centre, home to 24,000 people, the work place of 50,000 people and the focus of a tourism economy valued at £1 billion per annum. At the beginning of this new millennium, communication technology allows us to send images of Edinburgh’s World Heritage Site instantly around the globe, from the broadcasted spectacle of a Festival Fireworks display to the personal message from a visitor’s camera phone. It is our responsibility to treasure the Edinburgh World Heritage Site and to do so by embracing the past and enhancing the future. The World Heritage Site is neither a museum piece, nor a random collection of monuments. It is today a complex city centre which daily absorbs the energy of human endeavour. -

The Daniel Wilson Scrapbook

The Daniel Wilson Scrapbook Illustrations of Edinburgh and other material collected by Sir Daniel Wilson, some of which he used in his Memorials of Edinburgh in the olden time (Edin., 1847). The following list gives possible sources for the items; some prints were published individually as well as appearing as part of larger works. References are also given to their use in Memorials. Quick-links within this list: Box I Box II Box III Abbreviations and notes Arnot: Hugo Arnot, The History of Edinburgh (1788). Bann. Club: Bannatyne Club. Beattie, Caledonia illustrated: W. Beattie, Caledonia illustrated in a series of views [ca. 1840]. Beauties of Scotland: R. Forsyth, The Beauties of Scotland (1805-8). Billings: R.W. Billings, The Baronial and ecclesiastical Antiquities of Scotland (1845-52). Black (1843): Black’s Picturesque tourist of Scotland (1843). Black (1859): Black’s Picturesque tourist of Scotland (1859). Edinburgh and Mid-Lothian (1838). Drawings by W.B. Scott, engraved by R. Scott. Some of the engravings are dated 1839. Edinburgh delineated (1832). Engravings by W.H. Lizars, mostly after drawings by J. Ewbank. They are in two series, each containing 25 numbered prints. See also Picturesque Views. Geikie, Etchings: Walter Geikie, Etchings illustrative of Scottish character and scenery, new edn [1842?]. Gibson, Select Views: Patrick Gibson, Select Views in Edinburgh (1818). Grose, Antiquities: Francis Grose, The Antiquities of Scotland (1797). Hearne, Antiquities: T. Hearne, Antiquities of Great Britain illustrated in views of monasteries, castles and churches now existing (1807). Heriot’s Hospital: Historical and descriptive account of George Heriot’s Hospital. With engravings by J. -

Development Brief Princes Street Block 10 Approved by the Planning Commitee 15 May 2008 DEVELOPMENT BRIEF BLOCK 10

Development Brief Princes Street Block 10 Approved by the Planning Commitee 15 May 2008 DEVELOPMENT BRIEF BLOCK 10 Contents Page 1.0 Introduction 2 2.0 Site and context 2 3.0 Planning Policy Context 4 4.0 Considerations 6 4.1 Architectural Interest 4.2 Land uses 4.4 Setting 4.5 Transport and Movement 4.12 Nature Conservation/Historic Gardens and Designed Landscapes 4.16 Archaeological Interests 4.17 Contaminated land 4.18 Sustainability 5.0 Development Principles 12 6.0 Implementation 16 1 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Following the Planning Committee approval of the City Centre Princes Street Development Framework (CCPSDF) on 4 October 2007, the Council have been progressing discussions on the individual development blocks contained within the Framework area. The CCPSDF set out three key development principles based on reconciling the needs of the historic environment with contemporary users, optimising the site’s potential through retail-led mixed uses and creating a high quality built environment and public realm. It is not for this development brief to repeat these principles but to further develop them to respond to this area of the framework, known as Block 10. 1.2 The purpose of the development brief is to set out the main planning and development principles on which development proposals for the area should be based. The development brief will be a material consideration in the determination of planning applications that come forward for the area. 2.0 Site and context The Site 2.1 The development brief area is situated at the eastern end of the city centre and is the least typical of all the development blocks within the CCPSDF area. -

Appendix 2 OLD TOWN DRAFT CONSERVATION AREA

Appendix 2 OLD TOWN DRAFT CONSERVATION AREA CHARACTER APPRAISAL LOCATION AND BOUNDARIES The Old Town is an easily recognised entity within the wider city boundaries, formed along the spine of the hill which tails down from the steep Castle rock outcrop and terminates at the Palace of Holyroodhouse. It has naturally defined boundaries to the north, where the valley contained the old Nor’ Loch, and on the south the corresponding parallel valley of the Cowgate. The northern and western boundaries of the Conservation Area are well defined by the Castle and Princes Street Gardens, and to the east by Calton Hill and Calton Road. Arthur’s Seat, to the southeast, is a dominating feature which clearly defines the edge of the Conservation Area. DATES OF DESIGNATION/AMENDMENTS The Old Town Conservation Area was designated in July 1977 with amendments in 1982, 1986 and 1996. An Article 4 Direction Order which restricts normally permitted development rights was first made in 1984. WORLD HERITAGE STATUS The Old Town Conservation Area forms part of the Old and New Towns of Edinburgh World Heritage Site which was inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage Site list in 1995. This was in recognition of the outstanding architectural, historical and cultural importance of the Old and New Towns of Edinburgh. Inscription as a World Heritage Site brings no additional statutory powers. However, in terms of UNESCO’s criteria, the conservation and protection of the World Heritage Site are paramount issues. Inscription commits all those involved with the development and management of the Site to ensure measures are taken to protect and enhance the area for future generations. -

Edimburgo Edinburgh

INFORMACIÓN ELABORADA PARA: EDIMBURGO EDINBURGH PAÍS POBLACIÓN Reino Unido de Gran Bretaña (Escocia). 453.500 habitantes. BREVE DESCRIPCIÓN HISTÓRICA Capital de Escocia. Fue en su orígenes un campamento romano, siendo la ciudad fundada, según la tradición, a principios del siglo VII por el rey Edwinde Northumberland, del cual se deriva su nombre. En la historia aparece en la época de Malcolm III Canmore, quien, en la segunda mitad del siglo XI, mandó construir en ella su palacio real. Sede de los reyes de Escocia, que la ampliaron y embellecieron, se convirtió en capital del Reino en 1437. Ocupada y saqueada por los ingleses en 1544, después de la unión de Escocia con Inglaterra, en 1707, la ciudad fue escenario de agitaciones políticas y luchas religiosas. PLANO DE LA CIUDAD DÍAS FESTIVOS Ciudad de contrastes, de callejuelas y callejones 1 de enero Año nuevo. medievales, de amplias avenidas y calles en forma de 2 de enero Bank Holiday. semicírculo. 2 de mayo Day Bank Holiday. 30 de mayo Spring Bank Holiday. 1 de agosto Bank Holiday. 29 de agosto Summer Bank Holiday. Noviembre San Andrés, patrón de Escocia. 25 de diciembre Navidad. 26 de diciembre Boxing Day. FECHAS DESTACADAS Marzo/abril Edinburgh Folk Festival. Festival anual de música y danza folk, en los que participa el público. Agosto Edinburgh Military Tatto. En el castillo de Edimburgo. Espectacular exhibición nocturna de bandas militares escocesas. 1 Agosto/sept. Festival Internacional de HORARIOS DEL COMERCIO Edimburgo. Uno de los más famosos De 09,00 a 17,00/18,00 h. Algunas tiendas cierran el festivales del mundo. -

Ward, Christopher J. (2010) It's Hard to Be a Saint in the City: Notions of City in the Rebus Novels of Ian Rankin. Mphil(R) Thesis

Ward, Christopher J. (2010) It's hard to be a saint in the city: notions of city in the Rebus novels of Ian Rankin. MPhil(R) thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/1865/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] It’s Hard To Be A Saint In The City: Notions of City in the Rebus Novels of Ian Rankin Christopher J Ward Submitted for the degree of M.Phil (R) in January 2010, based upon research conducted in the department of Scottish Literature and Faculty of Arts, University of Glasgow © Christopher J Ward, 2010 Contents Acknowledgements 3 Introduction: The Crime, The Place 4 The juncture of two traditions 5 Influence and intent: the origins of Rebus 9 Combining traditions: Rebus comes of age 11 Noir; Tartan; Tartan Noir 13 Chapter One: Noir - The City in Hard-Boiled Fiction 19 Setting as mode: urban versus rural 20 Re-writing the Western: the emergence of hard-boiled fiction 23 The hard-boiled city as existential wasteland 27 ‘Down these mean streets a man must -

The Royal Mile, Edinburgh: a Preliminary Search for Authenticity One Year Later' University of Edinburgh Business School Working Paper Series, Vol

Edinburgh Research Explorer An Audit of a UNESCO World Heritage site - the Royal Mile, Edinburgh: a preliminary search for authenticity One year later Citation for published version: Harwood, S & El-Manstrly, D 2012 'An Audit of a UNESCO World Heritage site - the Royal Mile, Edinburgh: a preliminary search for authenticity One year later' University of Edinburgh Business School Working Paper Series, vol. 12-03, University of Edinburgh Business School. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Early version, also known as pre-print Publisher Rights Statement: © Harwood, S., & El-Manstrly, D. (2012). An Audit of a UNESCO World Heritage site - the Royal Mile, Edinburgh: a preliminary search for authenticity One year later. (University of Edinburgh Business School Working Paper Series). University of Edinburgh Business School. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 05. Oct. 2021 An Audit of a UNESCO World Heritage site - the Royal Mile, Edinburgh: a preliminary search for authenticity One year later Stephen A. Harwood, Dahlia El-Manstrly JULY 2012 UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH BUSINESS SCHOOL An Audit of a UNESCO World Heritage site - the Royal Mile, Edinburgh: a preliminary search for authenticity One year later Stephen A. -

Plan of Sanitary Improvements of the City of Edinburgh, August 17, 1866

PLAN 01'’ SANITARY IMPROVEMENTS OF THE CITY OF EDINBURGH. BY MESSRS COUSIN AND LESSEES, ARCHITECTS. AUGUST 17. 18GG. OTO&'K IMPROVEMENTS ;uion£7il^ PUVN OF PROJECTED . Qiarrity \P*y aWor-klTo. ^-<2 (ifKt/onu ARCHIT prtseni thorough enrwn entity so ' air 300 7QOO ScftBtH 'SeweAgi Manured ^WonJes fawner Tfo.irherl Wi/Treapof Crtur. ' V\ tra* signed "^1 Steam. Washing Mouse . faaisi S'nvgioam Ux)Spitiu' mr&/eQ' d Ya r , 1320 anii'i-U(*s School C attLe unity; ituekt rffi. \n< t st oy plaxk /zoz<l .Lrjfi Hsijpff iv .tA K. JOHNSTON. EDINBURGH PLAN OF SANITARY IMPROVEMENTS OF THE CITY OF EDINBURGH. BY MESSES COUSIN AND LESSEES, AECHITECTS. AUGUST 17. 1866. CITY IMPROVEMENT SCHEME. “ The Plans of tlio proposed Improvements, as prepared by Mr Cousin and Mr Lessels, with tbe relative Sections, will be open for inspection by tbe Public in the Council Chamber, for one month from this date. 1 ‘ The Lord Provost’s Committee will proceed, as early as possible in September, to consider the Plan in detail, along with such suggestions or observations thereon as may be lodged with the City Clerk on or before the 1st September next. “A small lithographed Plan of the proposed improvements, with an explanatory statement by Messrs Cousin and Lessels, and estimates of the cost, are in course of preparation, and will be circulated as soon as they can be got ready among the various public bodies. Copies, price 6d. each, will be supplied to the public by Messrs W. & A. K. Johnston, St Andrew Square. Intimation will be given by advertisement when the copies are ready for sale. -

The Transformation of Drumlanrig Castle at the End of Seventeenth-Century

First Construction History Conference Queens' College, Cambridge, 11th -12th of April 2014 González-Longo The transformation of Drumlanrig Castle at the end of seventeenth-century Cristina González-Longo, Department of Architecture, University of Strathclyde Abstract The transformation of Drumlanrig Castle between 1679-98 makes it one of the most original and interesting buildings of its time in Britain. It was carried out at almost the same time as the Royal Palace of Holyrood, whose design, construction and procurement influenced the making of Drumlanrig. James Smith, one of the mason-contractors at Holyrood, went to work at Drumlanrig as an independent architect for the first time, providing a unique design that was in continuity with local practices but also aware of contemporary Continental architectural developments. The careful selection of craftsmen, techniques and materials make this building one of the finest in Scotland. Although the original drawings and accounts of the project have now disappeared, it is possible to trace the history of its design and construction through a series of documents and drawings at Drumlanrig Castle and by looking at the building itself. This paper will unravel the transformation of the building at the end of seventeenth-century, identifying the people, skills, materials, technologies and practices involved and discussing how the design ideas were implemented during the construction. Figure 1: North elevation of Drumlanrig Castle Introduction John Summerson considered Drumlanrig Castle the most remarkable building emerging from the tradition initiated by the King Mastermason William Wallace (d.1631), ‘the last great gesture of the Scottish castle style’ and ‘obstinately Scottish’.[1] He did not make any reference to the fact that the building incorporates an earlier building, which makes it even 1 First Construction History Conference Queens' College, Cambridge, 11th -12th of April 2014 González-Longo more remarkable. -

My Favourite History Place Maggie Wilson Dinburgh’S Royal Mile Runs Between the Castle and Holyrood Palace

Gladstone’s Land Wellhead Witchs Well Advocates Close Riddles Court Railings for crinolines My Favourite History Place Maggie Wilson dinburgh’s Royal Mile runs between the Castle and Holyrood Palace. In addition to these and other well-known sites such as St Giles Cathedral, John whets our appetite Knox’s house, the Canongate Tolbooth and Canongate Kirk, and stories of for exploration of DeaconE Brodie, David Hume, James Boswell, Robert Burns and, obviously, Mary Queen of Scots, are hundreds of other less-visited gems. There must be more history Edinburgh’s Royal Mile. along the Royal Mile than any other street of similar length. Until the mid-eighteenth century all of Edinburgh, by then around 50,000 people, was housed in tenements either side of Castlehill, the Lawnmarket, the High Street and Canongate, which make up the mile-long stretch. Rich and poor, famous and infamous lived cheek by jowl in lands separated by narrow closes and wynds. These atmospheric alleys still exist and it takes little effort to imagine their past inhabitants. Tenements could be 12 storeys high. There was no main drainage so, after the 10pm curfew, windows high above the road were thrown open for the ejection of waste, including the contents of chamber pots. A cry of ‘Haud yer hand’ might save a late passer-by but Edinburgh in the eighteenth century was not called ‘Auld Reekie’ for nothing. Tenement – a room or set of rooms forming a separate residence within a While some buildings have been rebuilt or renovated, many are original, dating house or block of flats. -

HISTORY Scheinker Syndrome (GSS) Consequence Ofexposure Totheseinfected Individuals

J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2005; 35:268–274 PAPER © 2005 Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh Dangerous dissections: the hazard from bodies supplied to Edinburgh anatomists, winter session, 1848–9 MH Kaufman School of Biomedical and Clinical Laboratory Sciences, University of Edinburgh,Scotland ABSTRACT After the 1832 Anatomy Act,all bodies that were to be used by medical Correspondence to MH Kaufman, students for dissection were supplied to Schools of Anatomy based on their needs. School of Biomedical and Clinical During the Winter Session of 1848–9, a high proportion of the bodies supplied to Laboratory Sciences, Hugh Robson the University of Edinburgh, and the majority of those supplied to the Argyle Building, George Square, Edinburgh Square School had died of an infectious disease. Most had died from cholera, while EH8 9XD others had died of typhus, tuberculosis or other infectious diseases. These bodies tel. +44 (0)131 650 3113 were not embalmed before dissection. Therefore, both medical students and their teachers in Departments of Anatomy, in addition to those in the hospitals in which fax. +44 (0)131 650 3711 they had died, would have been at risk of becoming infected or even dying as a consequence of exposure to these infected individuals. e-mail [email protected] KEYWORDS Infected bodies, Schools of Anatomy, cholera, typhus, tuberculosis, bodies not embalmed, risk of infection LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS Creutzfeldt Jacob Disease (CJD), Gerstmann-Straussler- Scheinker syndrome (GSS) DECLARATION OF INTEREST No conflict of interests declared. Shortly after the implementation of the 1832 Anatomy and therefore had relatively little difficulty in obtaining an Act,1 there was considerable concern in the various adequate number for this purpose, this tended to be the extra-mural schools in Edinburgh, all of which were exception rather than the rule.