Pseudorca Crassidens)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Captive Orcas

Captive Orcas ‘Dying to Entertain You’ The Full Story A report for Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society (WDCS) Chippenham, UK Produced by Vanessa Williams Contents Introduction Section 1 The showbiz orca Section 2 Life in the wild FINgerprinting techniques. Community living. Social behaviour. Intelligence. Communication. Orca studies in other parts of the world. Fact file. Latest news on northern/southern residents. Section 3 The world orca trade Capture sites and methods. Legislation. Holding areas [USA/Canada /Iceland/Japan]. Effects of capture upon remaining animals. Potential future capture sites. Transport from the wild. Transport from tank to tank. “Orca laundering”. Breeding loan. Special deals. Section 4 Life in the tank Standards and regulations for captive display [USA/Canada/UK/Japan]. Conditions in captivity: Pool size. Pool design and water quality. Feeding. Acoustics and ambient noise. Social composition and companionship. Solitary confinement. Health of captive orcas: Survival rates and longevity. Causes of death. Stress. Aggressive behaviour towards other orcas. Aggression towards trainers. Section 5 Marine park myths Education. Conservation. Captive breeding. Research. Section 6 The display industry makes a killing Marketing the image. Lobbying. Dubious bedfellows. Drive fisheries. Over-capturing. Section 7 The times they are a-changing The future of marine parks. Changing climate of public opinion. Ethics. Alternatives to display. Whale watching. Cetacean-free facilities. Future of current captives. Release programmes. Section 8 Conclusions and recommendations Appendix: Location of current captives, and details of wild-caught orcas References The information contained in this report is believed to be correct at the time of last publication: 30th April 2001. Some information is inevitably date-sensitive: please notify the author with any comments or updated information. -

THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity Authors: Naomi A

s l a m m a y t T i M S N v I i A e G t A n i p E S r a A C a C E H n T M i THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity The Humane Society of the United State s/ World Society for the Protection of Animals 2009 1 1 1 2 0 A M , n o t s o g B r o . 1 a 0 s 2 u - e a t i p s u S w , t e e r t S h t u o S 9 8 THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity Authors: Naomi A. Rose, E.C.M. Parsons, and Richard Farinato, 4th edition Editors: Naomi A. Rose and Debra Firmani, 4th edition ©2009 The Humane Society of the United States and the World Society for the Protection of Animals. All rights reserved. ©2008 The HSUS. All rights reserved. Printed on recycled paper, acid free and elemental chlorine free, with soy-based ink. Cover: ©iStockphoto.com/Ying Ying Wong Overview n the debate over marine mammals in captivity, the of the natural environment. The truth is that marine mammals have evolved physically and behaviorally to survive these rigors. public display industry maintains that marine mammal For example, nearly every kind of marine mammal, from sea lion Iexhibits serve a valuable conservation function, people to dolphin, travels large distances daily in a search for food. In learn important information from seeing live animals, and captivity, natural feeding and foraging patterns are completely lost. -

213 Subpart I—Taking and Importing Marine Mammals

National Marine Fisheries Service/NOAA, Commerce Pt. 218 regulations or that result in no more PART 218—REGULATIONS GOV- than a minor change in the total esti- ERNING THE TAKING AND IM- mated number of takes (or distribution PORTING OF MARINE MAM- by species or years), NMFS may pub- lish a notice of proposed LOA in the MALS FEDERAL REGISTER, including the asso- ciated analysis of the change, and so- Subparts A–B [Reserved] licit public comment before issuing the Subpart C—Taking Marine Mammals Inci- LOA. dental to U.S. Navy Marine Structure (c) A LOA issued under § 216.106 of Maintenance and Pile Replacement in this chapter and § 217.256 for the activ- Washington ity identified in § 217.250 may be modi- fied by NMFS under the following cir- 218.20 Specified activity and specified geo- cumstances: graphical region. (1) Adaptive Management—NMFS 218.21 Effective dates. may modify (including augment) the 218.22 Permissible methods of taking. existing mitigation, monitoring, or re- 218.23 Prohibitions. porting measures (after consulting 218.24 Mitigation requirements. with Navy regarding the practicability 218.25 Requirements for monitoring and re- porting. of the modifications) if doing so cre- 218.26 Letters of Authorization. ates a reasonable likelihood of more ef- 218.27 Renewals and modifications of Let- fectively accomplishing the goals of ters of Authorization. the mitigation and monitoring set 218.28–218.29 [Reserved] forth in the preamble for these regula- tions. Subpart D—Taking Marine Mammals Inci- (i) Possible sources of data that could dental to U.S. Navy Construction Ac- contribute to the decision to modify tivities at Naval Weapons Station Seal the mitigation, monitoring, or report- Beach, California ing measures in a LOA: (A) Results from Navy’s monitoring 218.30 Specified activity and specified geo- graphical region. -

Killer Controversy, Why Orcas Should No Longer Be Kept in Captivity

Killer Controversy Why orcas should no longer be kept in captivity ©Naomi Rose - HSI Prepared by Naomi A. Rose, Ph.D. Senior Scientist September 2011 The citation for this report should be as follows: Rose, N. A. 2011. Killer Controversy: Why Orcas Should No Longer Be Kept in Captivity. Humane Society International and The Humane Society of the United States, Washington, D.C. 16 pp. © 2011 Humane Society International and The Humane Society of the United States. All rights reserved. i Table of Contents Table of Contents ii Introduction 1 The Evidence 1 Longevity/survival rates/mortality 1 Age distribution 4 Causes of death 5 Dental health 5 Aberrant behavior 7 Human injuries and deaths 8 Conclusion 8 Ending the public display of orcas 9 What next? 10 Acknowledgments 11 ii iii Killer Controversy Why orcas should no longer be kept in captivity Introduction Since 1964, when a killer whale or orca (Orcinus orca) was first put on public display1, the image of this black-and-white marine icon has been rehabilitated from fearsome killer to cuddly sea panda. Once shot at by fishermen as a dangerous pest, the orca is now the star performer in theme park shows. But both these images are one-dimensional, a disservice to a species that may be second only to human beings when it comes to behavioral, linguistic, and ecological diversity and complexity. Orcas are intelligent and family-oriented. They are long-lived and self- aware. They are socially complex, with cultural traditions. They are the largest animal, and by far the largest predator, held in captivity. -

Killer Whale) Orcinus Orca

AMERICAN CETACEAN SOCIETY FACT SHEET P.O. Box 1391 - San Pedro, CA 90733-1391 - (310) 548-6279 ORCA (Killer Whale) Orcinus orca CLASS: Mammalia ORDER: Cetacea SUBORDER: Odontoceti FAMILY: Delphinidae GENUS: Orcinus SPECIES: orca The orca, or killer whale, with its striking black and white coloring, is one of the best known of all the cetaceans. It has been extensively studied in the wild and is often the main attraction at many sea parks and aquaria. An odontocete, or toothed whale, the orca is known for being a carnivorous, fast and skillful hunter, with a complex social structure and a cosmopolitan distribution (orcas are found in all the oceans of the world). Sometimes called "the wolf of the sea", the orca can be a fierce hunter with well-organized hunting techniques, although there are no documented cases of killer whales attacking a human in the wild. PHYSICAL SHAPE The orca is a stout, streamlined animal. It has a round head that is tapered, with an indistinct beak and straight mouthline. COLOR The orca has a striking color pattern made up of well-defined areas of shiny black and cream or white. The dorsal (top) part of its body is black, with a pale white to gray "saddle" behind the dorsal fin. It has an oval, white eyepatch behind and above each eye. The chin, throat, central length of the ventral (underside) area, and undersides of the tail flukes are white. Each whale can be individually identified by its markings and by the shape of its saddle patch and dorsal fin. -

The Whale, Inside: Ending Cetacean Captivity in Canada* Katie Sykes**

The Whale, Inside: Ending Cetacean Captivity in Canada* Katie Sykes** Canada has just passed a law making it illegal to keep cetaceans (whales and dolphins) in captivity for display and entertainment: the Ending the Captivity of Whales and Dolphins Act (Bill S-203). Only two facilities in the country still possess captive cetaceans: Marineland in Niagara Falls, Ontario; and the Vancouver Aquarium in Vancouver, British Columbia. The Vancouver Aquarium has announced that it will voluntarily end its cetacean program. This article summarizes the provisions of Bill S-203 and recounts its eventful journey through the legislative process. It gives an overview of the history of cetacean captivity in Canada, and of relevant existing 2019 CanLIIDocs 2114 Canadian law that regulates the capture and keeping of cetaceans. The article argues that social norms, and the law, have changed fundamentally on this issue because of several factors: a growing body of scientific research that has enhanced our understanding of cetaceans’ complex intelligence and social behaviour and the negative effects of captivity on their welfare; media investigations by both professional and citizen journalists; and advocacy on behalf of the animals, including in the legislative arena and in the courts. * This article is current as of June 17, 2019. It has been partially updated to reflect the passage of Bill S-203 in June 2019. ** Katie Sykes is Associate Professor of Law at Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops, British Columbia. Her research focuses on animal law and on the future of the legal profession. She is co-editor, with Peter Sankoff and Vaughan Black, of Canadian Perspectives on Animals and the Law (Toronto: Irwin Law, 2015) the first book-length jurisprudential work to engage in a sustained analysis of Canadian law regulating the treatment of non-human animals at the hands of human beings. -

False Killer Whale Fact Sheet

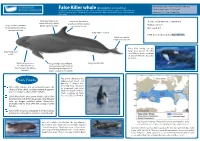

False Killer whale (pseudorca crassidens) Adult length: Up to 6m (male)/5m (female) Distribution: coastal and primarily offshore waters in tropical and temperate regions (see map below and Adult weight: up to 2,000kg (m) full list of countries in the detailed species account online at: https://wwhandbook.iwc.int/en/species/false- Newborn: 1.6-1.9m /Unknown killer-whale Dark grey/black body Prominent dorsal fin is Threats: entanglement, contaminants colour with only a faintly usually curved and slightly Habitat: offshore Long, slender head tapers darker cape (variable) rounded at the tip to rounded snout with no Diet: squid, fish pronounced beak Body may be scarred IUCN Conservation status: Data deficient Flukes are small in relation to body size False killer whales can eat Head hangs over large prey species like this mouth Ono/Wahoo. photo courtesy of Daniel Webster, Cascadia Reserach Lighter grey anchor or Long strongly curved flipper Long, slender body “W” shaped patch on with a pronounced corner or chest between the flippers bend giving the flipper an ‘S’ (variable) shape – unique to this species This photo illustrates the Fun Facts bullet-shaped head and typically ‘S’ shaped flip- pers that help observers False killer whales are so named because the to distinguish false killer shape of their skulls, not their external appear- ance, is similar to that of killer whales. whales from pilot whales. Photo courtesy of Paula Like killer whales and sperm whales, false killer Olson/SEFSC/NOAA. whales form stable family groups, and females who no longer produce calves themselves probably help to look after the young of other females False killer whales participate in prey-sharing; a behaviour thought to reinforce social bonds False Killer whale distribution. -

Benthic Foraging on Stingrays by Killer Whales (Orcinus Orca) in New Zealand Waters

220 MARINE MAMMAL SCIENCE, VOL. 15, NO. 1, 1999 demii Nauk SSSR, Moskow (translated by the Israel Program for scientific Trans- lations, Jerusalem, 1967). 717 pp. VON ZIEGESAR,0. 1992. A catalogue of Prince William Sound humpback whales identified by fluke photographs between the years 1977 and 1991. Report to the National Marine Mammal Laboratory, NMFS, NOAA, by the North Gulf Oceanic Society, P. 0. Box 15244, Homer, AK 99603. VON ZIEGESAR,O., E. MILLERAND M. E. DAHLHEIM.1994. Impacts on humpback whales in Prince William Sound. Pages 173-191 in T. R. Loughlin, ed. Marine mammals and the Exxon Vuldez. Academic Press. JANICEM. WAITE,MARILYN E. DAHLHEIM,RODERICK C. HOBBS,SALLY A. MIZROCH,NOAA, Alaska Fisheries Science Center, National Marine Mammal Laboratory, 7600 Sand Point Way N. E., Seattle, Washington 98115-0070, U.S.A.; e-mail: [email protected]; OLGAVON ZIEGESAR-MATKIN,North Gulf Oceanic Society, P.O. Box 15244, Homer, Alaska 99603, U.S.A.;JANICE M. STRALEY,P.O. Box 273, Sitka, Alaska 99835, U.S.A.; LOUISM. HERMAN, Kewalo Basin Marine Mammal Laboratory, University of Hawaii, 1129 Ala Moana Boulevard, Honolulu, Hawaii 968 14, U.S.A.; JEFFJACOBSEN, P.O. Box 4492, Arcata, CA 95521, U.S.A. Received 15 July 1994. Accepted 20 Feb- ruary 1998. MARINE MAMMAL SCIENCE, 15(1):220-227 (January 1999) 0 1999 by the Society for Marine Mammalogy BENTHIC FORAGING ON STINGRAYS BY KILLER WHALES (ORCINUS ORCA) IN NEW ZEALAND WATERS One method of foraging not previously reported for the killer whale is benthic foraging. This paper describes frequent feeding by killer whales on rays in shallow water off the North Island of New Zealand. -

Pseudorca Crassidens) and Nine Other Odontocete Species from Hawai‘I

Ecotoxicology DOI 10.1007/s10646-014-1300-0 Cytochrome P4501A1 expression in blubber biopsies of endangered false killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) and nine other odontocete species from Hawai‘i Kerry M. Foltz • Robin W. Baird • Gina M. Ylitalo • Brenda A. Jensen Accepted: 2 August 2014 Ó Springer Science+Business Media New York 2014 Abstract Odontocetes (toothed whales) are considered insular false killer whale. Significantly higher levels of sentinel species in the marine environment because of their CYP1A1 were observed in false killer whales and rough- high trophic position, long life spans, and blubber that toothed dolphins compared to melon-headed whales, and in accumulates lipophilic contaminants. Cytochrome general, trophic position appears to influence CYP1A1 P4501A1 (CYP1A1) is a biomarker of exposure and expression patterns in particular species groups. No sig- molecular effects of certain persistent organic pollutants. nificant differences in CYP1A1 were found based on age Immunohistochemistry was used to visualize CYP1A1 class or sex across all samples. However, within male false expression in blubber biopsies collected by non-lethal killer whales, juveniles expressed significantly higher lev- sampling methods from 10 species of free-ranging els of CYP1A1 whenP compared to adults. Total polychlo- Hawaiian odontocetes: short-finned pilot whale, melon- rinated biphenyl ( PCBs) concentrations in 84 % of false headed whale, pygmy killer whale, common bottlenose killer whalesP exceeded proposed threshold levels for health dolphin, rough-toothed dolphin, pantropical spotted dol- effects, and PCBs correlated with CYP1A1 expression. phin, Blainville’s beaked whale, Cuvier’s beaked whale, There was no significant relationship between PCB toxic sperm whale, and endangered main Hawaiian Islands equivalent quotient and CYP1A1 expression, suggesting that this response may be influenced by agonists other than the dioxin-like PCBs measured in this study. -

False Killer Whale Dorsal Fin Disfigurements As A

False Killer Whale Dorsal Fin Disfigurements as a Possible Indicator of Long-Line Fishery Interactions in Hawaiian Waters1 Robin W. Baird 2 and Antoinette M. Gorgone3 Abstract: Scarring resulting from entanglement in fishing gear can be used to examine cetacean fishery interactions. False killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) are known to interact with the Hawai‘i-based tuna and swordfish long-line fish- ery in offshore Hawaiian waters. We examined the rate of major dorsal fin dis- figurements of false killer whales from nearshore waters around the main Hawaiian Islands to assess the likelihood that individuals around the main is- lands are part of the same population that interacts with the fishery. False killer whales were encountered on 11 occasions between 2000 and 2004, and 80 dis- tinctive individuals were photographically documented. Three of these (3.75%) had major dorsal fin disfigurements (two with the fins completely bent over and one missing the fin). Information from other research suggests that the rate of such disfigurements for our study population may be more than four times greater than for other odontocete populations. We suggest that the most likely cause of such disfigurements is interactions with longlines and that false killer whales found in nearshore waters around the main Hawaiian Islands are part of the same population that interacts with the fishery. Two of the animals docu- mented with disfigurements had infants in close attendance and were thought to be adult females. This implies that even with such injuries, at least some fe- males may be able to produce offspring, despite the importance of the dorsal fin in reproductive thermoregulation. -

Killer Whale (Orcinus Orca) Occurrence and Predation in the Bahamas

Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, page 1 of 5. # Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 2013 doi:10.1017/S0025315413000908 Killer whale (Orcinus orca) occurrence and predation in the Bahamas charlotte dunn and diane claridge Bahamas Marine Mammal Research Organisation, PO Box AB-20714, Marsh Harbour, Abaco, Bahamas Killer whales (Orcinus orca) have a cosmopolitan distribution, yet little is known about populations that inhabit tropical waters. We compiled 34 sightings of killer whales in the Bahamas, recorded from 1913 to 2011. Group sizes were generally small (mean ¼ 4.2, range ¼ 1–12, SD ¼ 2.6). Thirteen sightings were documented with photographs and/or video of suffi- cient quality to allow individual photo-identification analysis. Of the 45 whales photographed, 14 unique individual killer whales were identified, eight of which were re-sighted between two and nine times. An adult female (Oo6) and a now-adult male (Oo4), were first seen together in 1995, and have been re-sighted together eight times over a 16-yr period. To date, killer whales in the Bahamas have only been observed preying on marine mammals, including Atlantic spotted dolphin (Stenella frontalis), Fraser’s dolphin (Lagenodelphis hosei), pygmy sperm whale (Kogia breviceps) and dwarf sperm whale (Kogia sima), all of which are previously unrecorded prey species for Orcinus orca. Keywords: killer whales, Bahamas, predation, Atlantic, Orcinus orca Submitted 30 December 2012; accepted 15 June 2013 INTRODUCTION encounters with killer whales documented during dedicated marine mammal surveys. Since 1991, marine mammal sight- Killer whales are predominantly temperate or cold water species ing reports have been obtained through a public sighting and much is known about their distribution, behavioural ecology network established and maintained by the Bahamas Marine and localized abundance in colder climes (Forney & Wade, Mammal Research Organization (BMMRO). -

(Orcinus Orca) and Hammerhead Sharks (Sphyrna Sp.) in Galápagos Waters

LAJAM 5(1): 69-71, June 2006 ISSN 1676-7497 INTERACTION BETWEEN KILLER WHALES (ORCINUS ORCA) AND HAMMERHEAD SHARKS (SPHYRNA SP.) IN GALÁPAGOS WATERS LUCA SONNINO SORISIO1, ALESSANDRO DE MADDALENA2 AND INGRID N. VISSER3,4 ABSTRACT: A possible predatory interaction between killer whales (Orcinus orca) and hammerhead sharks (Sphyrna sp.) was observed during April 1991 near Punta Cormorant, Galápagos Islands. Three killer whales were observed in close proximity to a freshly dead female hammerhead. One of the killer whales (approximately 6m in length) was observed motionless in a vertical position above the shark carcass and later was seen chasing an approximately 40cm hammerhead, supposedly a pup born prematurely from the dead shark. The sharks are thought to have been scalloped hammerheads (S. lewini). RESÚMEN: Una posible interacción predatoria entre orcas (Orcinus orca) y peces martillo (Sphyrna sp.) fue observada en Abril de 1991 cerca de Punta Cormorán, Islas Galápagos. Tres orcas fueron vistas muy próximas a una hembra de pez martillo recién muerta. Una de las orcas (de unos 6m de longitud), fue observada inmóvil en posición vertical sobre la carcasa del tiburón y después fue vista persiguiendo a un pez martillo de unos 40cm, supuestamente una cría nacida prematuramente de la hembra muerta. Se piensa que los tiburones pudieran ser cornudas negras (S. lewini). KEYWORDS: killer whale; Orcinus orca; hammerhead shark; Sphyrna; predation. Observations of killer whales (Orcinus orca) feeding on, the infrequent sightings and even rarer number of or attacking sharks are relatively infrequent (Table 1). observations of killer whale predation off the Galápagos Reports of killer whales off the Galápagos Islands are Islands, we report here on a possible predatory not common (e.g., Day, 1994; Merlen, 1999; Smith and interaction between killer whales and hammerhead Whitehead, 1999) as during a 27-year period of record sharks (Sphyrna sp.).