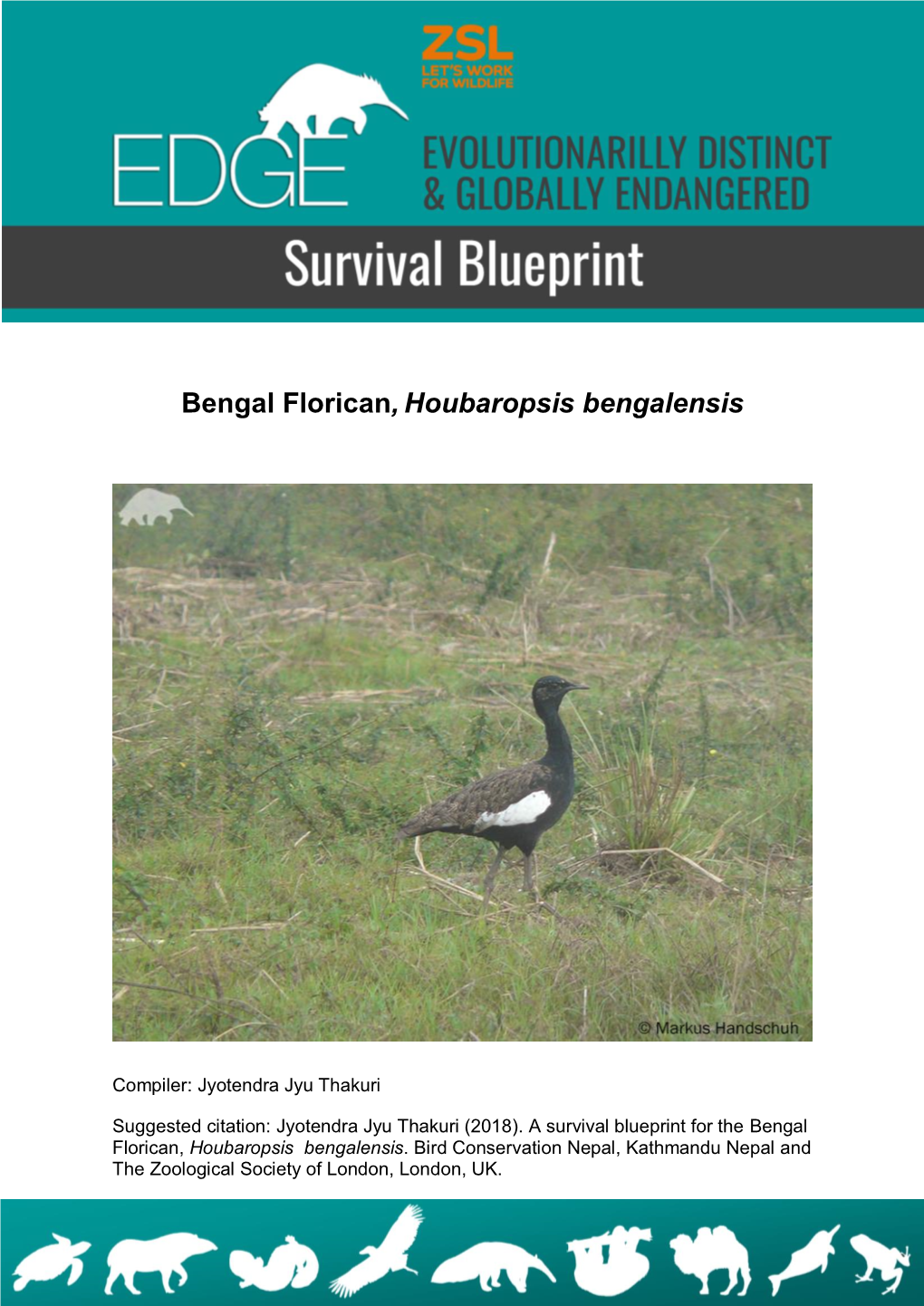

Bengal Florican,Houbaropsis Bengalensis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CEE Lesser Florican Community Leadership Programme, India

Lesser Florican Community Leadership Programme, India Project Code 100080 BP Conservation Leadership Programme Future Conservationist Award 2008 Final Report Supriya Jhunjhunwala& Anirban Dutta Gupta CEE TABLE OF CONTENTS: 1. Acknowledgments 2. Project Fact Sheet 3. Introduction 4. Species Description: Habitat Preferences, Distribution & Breeding 5. Threats & Conservation Status 6. Study Site 7. Programme Objectives 7.1 Objective 1: To Conserve the Lesser Florican and its habitat, Methods and Outputs 7.2 Objective 2: Developing and disseminating conservation education material; 7.3 Objective 3: Empowering stakeholder communities through community leadership programmes; 7.4 Objective 4: To disseminate learning’s to a wide stakeholder group, Methods and Outputs 7.5 Objective 5: To support ongoing local level conservation programmes; Methods and Outputs 7.6 Objective 6: To raise levels of awareness about the species and site; Methods and Outputs 7.7 Objective 7: To influence policy detrimental to the conservation of the Lesser Florican 8. Conservation Impact 9. Recommendation 10. Future Goals 11 Conclusion 12. Details of Expenditure 13. References CEE 1. ACKNOWLEDGMENT We would like to thank the following for their support: Madhya Pradesh Forest Department Mr. P. Gangopadhyay, Former PCCF, Mr. H. S. Pabla, Former Additional PCCF, Mr. P. M. Laad, Former PCCF , Mr. Vivek Jain, DFO Ratlam, Mr. Sanjeev Jhah, DFO Ratlam Mr. R.S Singod, Deputy Ranger Ratlam, Mr. D.K. Rajora, Range Officer Sailana ,Mr. Dashrat Singh Pawar, Van Rakshak Khimaji Mailda, fellow naturalist and field worker par excellence Mr. BMS Rathore, Senior Advisor, Winrock International India Mr. Bharat Singhji Former Forest Minister and Home Minister, Govt. of Madhya Pradesh Dr. -

A Description of Copulation in the Kori Bustard J Ardeotis Kori

i David C. Lahti & Robert B. Payne 125 Bull. B.O.C. 2003 123(2) van Someren, V. G. L. 1918. A further contribution to the ornithology of Uganda (West Elgon and district). Novitates Zoologicae 25: 263-290. van Someren, V. G. L. 1922. Notes on the birds of East Africa. Novitates Zoologicae 29: 1-246. Sorenson, M. D. & Payne, R. B. 2001. A single ancient origin of brood parasitism in African finches: ,' implications for host-parasite coevolution. Evolution 55: 2550-2567. 1 Stevenson, T. & Fanshawe, J. 2002. Field guide to the birds of East Africa. T. & A. D. Poyser, London. Sushkin, P. P. 1927. On the anatomy and classification of the weaver-birds. Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist. Bull. 57: 1-32. Vernon, C. J. 1964. The breeding of the Cuckoo-weaver (Anomalospiza imberbis (Cabanis)) in southern Rhodesia. Ostrich 35: 260-263. Williams, J. G. & Keith, G. S. 1962. A contribution to our knowledge of the Parasitic Weaver, Anomalospiza s imberbis. Bull. Brit. Orn. Cl. 82: 141-142. Address: Museum of Zoology and Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of " > Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109, U.S.A. email: [email protected]. 1 © British Ornithologists' Club 2003 I A description of copulation in the Kori Bustard j Ardeotis kori struthiunculus \ by Sara Hallager Received 30 May 2002 i Bustards are an Old World family with 25 species in 6 genera (Johnsgard 1991). ? Medium to large ground-dwelling birds, they inhabit the open plains and semi-desert \ regions of Africa, Australia and Eurasia. The International Union for Conservation | of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Animals lists four f species of bustard as Endangered, one as Vulnerable and an additional six as Near- l Threatened, although some species have scarcely been studied and so their true I conservation status is unknown. -

CONCERTED ACTION for the BENGAL FLORICAN (Houbaropsis Bengalensis Bengalensis)*

CONVENTION ON UNEP/CMS/COP13/Doc.28.2.11/Rev.1 MIGRATORY 23 January 2020 SPECIES Original: English 13th MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Gandhinagar, India, 17 - 22 February 2020 Agenda Item 28.2.11 PROPOSAL FOR A CONCERTED ACTION FOR THE BENGAL FLORICAN (Houbaropsis bengalensis bengalensis)* Summary: The Government of India has submitted the attached proposal for a Concerted Action for the Bengal Florican (Houbaropsis bengalensis bengalensis) in accordance with the process elaborated in Resolution 12.28. This revised version modifies the taxonomic scope of the proposal with a view to align it with the corresponding listing proposal. *The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CMS Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author UNEP/CMS/COP13/Doc.28.2.11/Rev.1 Proposal for Concerted Actions CMS COP 13 2020 Bengal Florican Houbaropsis bengalensis Proponent India (Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change) Target Species, Bengal Florican Houbaropsis bengalensis bengalensis (J.F. Lower taxon or Gmelin, 1789) population, or group of taxa with Only H. b. bengalensis is proposed for inclusion in Appendix I of needs in common CMS Convention. The proposed Concerted Action is therefore foreseen to focus on this subspecies. However, it is anticipated that individual activities might concern and support the conservation of the other recognized subspecies, Houbaropsis b. -

Conservation Status of Bengal Florican Houbaropsis Bengalensis

Cibtech Journal of Zoology ISSN: 2319–3883 (Online) An Online International Journal Available at http://www.cibtech.org/cjz.htm 2013 Vol. 2 (1) January-April, pp.61-69/Harish Kumar Research Article CONSERVATION STATUS OF BENGAL FLORICAN HOUBAROPSIS BENGALENSIS IN DUDWA TIGER RESERVE, UTTAR PRADESH, INDIA *Harish Kumar WWF-India, Dehradun Program Office, 32-1/72 Pine Hall School Lane, Rajpur Road, Dehradun, Uttarakhand-248001. *Author for Correspondence ABSTRACT Surveys for Bengal Florican were conducted in 2000 and 2001to assess the status and distribution of the species in Dudhwa National Park and Kishanpur WLS. The different grasslands were surveyed and from 26 different grassland sites 36 floricans were recorded. Males were most of the time in display and females were recorded from four different grasslands walking in Saccharum narenga and Sachharum sponteneum grass patches. The present study also recorded 36 different individuals thus a population of 72 floricans in the Dudwa Tiger Reserve The grasslands in Dudhwa after burning practices provides a good display ground for the floricans and a mosaic of upland grasslands Impreta cylindrica – Sacchrum spontaneum and low land Sacchrum narenga – Themeda arundancea provides ideal habitat for floricans in the Dudhwa NP and Kishanpur WLS. INTRODUCTION The Bengal Florican, Houbaropsis bengalensis (Gmelin 1789) is identified as critically endangered among the bustards by IUCN and global population is estimated at fewer than 400 individuals in the Indian subcontinent (Anon 2011). The Bengal Florican is listed in the Schedule I of the Indian Wildlife Protection Act. Distributed in the subcontinent in Assam, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal, West Bengal and the terai of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh (Ali and Ripley 1987), it is now considered one of the most endangered bustards of the world. -

International Protection for Great Indian Bustard, Bengal Florican And

Source : www.pib.nic.in Date : 2020-02-21 INTERNATIONAL PROTECTION FOR GREAT INDIAN BUSTARD, BENGAL FLORICAN AND ASIAN ELEPHANT Relevant for: Environment | Topic: Biodiversity, Ecology, and Wildlife Related Issues Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change International protection for Great Indian Bustard, Bengal Florican and Asian Elephant Posted On: 20 FEB 2020 7:52PM by PIB Delhi India’s proposal to include Great Indian Bustard, Asian Elephant and Bengal Florican in Appendix I of UN Convention on migratory species was unanimously accepted today at the ongoing thirteenth Conference of the Parties to the Convention on MigratorySpecies (CMS) in Gandhinagar. Asian Elephant The Government of India has declared Indian elephant as National Heritage Animal. Indian elephant is also provided highest degree of legal protection by listing it in Schedule I of the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972. #UPDATE :#CMSCOPIndia India's proposal to include mainland Asian elephant in Appendix I of @BonnConvention accepted unanimously. Move will promote conservation of Asian Elephant in its natural habitat as well as to reduce human elephant conflict in range countries.#CMSCOP13 pic.twitter.com/PgTRS9GOJX — PIB India (@PIB_India) February 20, 2020 Placing Indian elephant in Schedule I of the CMS Convention, will fulfil natural urge of migration of Indian elephant across India’s borders and back safely and thereby promote conservation of this endangered species for our future generations. Intermixing of smaller sub populations in Nepal, Bangladesh, Bhutan and Myanmar and widen the gene base of these populations. It will also help to reduce human elephant conflicts in many parts of its migratory routes. MainlandcrackIAS.com Asian elephants/Indian elephants migrate over long distances in search of food and shelter, across States and Countries. -

Distribution, Status and Conservation of the Bengal Florican Houbaropsis Bengalensis in Cambodia

Bird Conservation International (2009) 19:1–14. ª BirdLife International 2009 doi:10.1017/S095927090800765X Printed in the United Kingdom Distribution, status and conservation of the Bengal Florican Houbaropsis bengalensis in Cambodia THOMAS N. E. GRAY, NIGEL J. COLLAR, PETER J. A. DAVIDSON, PAUL M. DOLMAN, TOM D. EVANS, HARRY N. FOX, HONG CHAMNAN, RO BOREY, SENG KIM HOUT and ROBERT N. VAN ZALINGE Summary The Bengal Florican is a ‘Critically Endangered’ bustard (Otididae) restricted to India, Nepal and southern Indochina. Fewer than 500 birds are estimated to remain in the Indian subcontinent, whilst the Indochinese breeding population is primarily restricted to grasslands surrounding the Tonle Sap lake, Cambodia. We conducted the first comprehensive breeding season survey of 2 Bengal Florican within the Tonle Sap region (19,500 km ). During 2005/06 and 2006/07 we systematically sampled 1-km squares for territorial males. Bengal Florican were detected within 2 90 1-km squares at a mean density of 0.34 males kmÀ which, accounting for unequal survey 2 effort across grassland blocks, provides a mean estimate of 0.2 males kmÀ . Based on 2005 habitat extent, the estimated Tonle Sap population is 416 adult males (333–502 6 95% CI), more than half of them in Kompong Thom province. Tonle Sap grasslands are rapidly being lost due to intensification of rice cultivation and, based on satellite images, we document declines of 28% grassland cover within 10 grassland blocks between January 2005 and March 2007. Based on mean 2005 population densities the remaining grassland may support as few as 294 adult male 2 florican, a decline of 30% since 2005. -

To Read More

Draft of Final Report – PEP Bengal Florican Landscape level conservation of the Bengal Florican Houbaropsis bengalensis bengalensis through research and advocacy in Uttar Pradesh Final report November 2017 1 | P a g e Draft of Final Report – PEP Bengal Florican Landscape level conservation of the Bengal Florican Houbaropsis bengalensis bengalensis through research and advocacy in Uttar Pradesh Final Report November 2017 Principal Investigator Dr. Deepak Apte Co- Principal Investigator Dr. Sujit Narwade Senior Scientist Dr. Rajat Bhargav Scientists Ngulkholal Khongsai Research Fellows Rohit Jha (December 2016-February 2017) Balasaheb Lambture 2 | P a g e Draft of Final Report – PEP Bengal Florican Recommended citation Narwade, S.S., Lambture, B.R., Khongsai, N., Jha, R., Bhargav, R. and Apte, D. (2017): Landscape level conservation of the Bengal Florican Houbaropsis bengalensis bengalensis through research and advocacy in Uttar Pradesh. Report submitted by BNHS. Pp 30. BNHS Mission: Conservation of Nature, primarily Biological Diversity through action based on Research, Education and Public Awareness © BNHS 2017: All rights reserved. This publication shall not be reproduced either in full original part in any form, either in print or electronic or any other medium, without the prior written permission of the Bombay Natural History Society. Disclaimer: Google Earth Maps provided in the report are based on observations carried out by the BNHS team. Actual size and structure of the size may vary on ground. Address and contact details Bombay -

Table of Content

UNESCO- IUCN Enhancing Our Heritage Project: Monitoring and Managing for Success in Natural World Heritage Sites Final Management Effectiveness Evaluation Report Kaziranga National Park, Assam, India November 2007 Table of Content Project Background 1 How the Evaluation was carried out 2 The Project Workbook and Tool Kits 3 Section 1: Introduction 4-7 Section 2: Context and Planning Assessment 8-36 Tool 1: Identifying Site Values and Management Objectives 11 Tool 2: Identifying Threats 14 Tool 3: Engagement of Stakeholder/Partners 28 Tool 4: Review of National Context 35 Section 3: Planning 37-48 Tool 5: Assessment of Management Planning 37 Tool 6: Design Assessment 44 Section 4: Inputs and Process Assessment 49-51 Tool 7: Assessment of Management Needs and Inputs 49 Section 5: Assessment of Management Process 52-64 Tool 8: Assessment of Management Processes 52 Section 6: Outputs 65-69 Tool 9: Assessment of Management Plan Implementation 66 Tool 10: Assessment of Work/Site Output Indicators 67 Section 7: Outcomes 70-78 Tool 11: Assessing the Outcomes of Management – Ecological Integrity 70 Tool 12: Assessing the Outcomes of Management – Achievement of Principal Objectives 75 List of Boxes Box 1: Kaziranga National Park ~ 100 Years of Success Story 5 Box 2: IUCN-WCPA framework for Management Effectiveness Evaluation 7 Box 3: Protection Strategy 17 Box 4: Conservation of Beels for Waterbirds in Kaziranga National Park, Assam 20 Box 5: Management of Invasive Species in Kaziranga National Park, Assam 24 Box 6: Declaration of Kaziranga Tiger Reserve in 2007 46 Box 7 Raptor community of Kaziranga National Park, Assam 72 Box 8: Kaziranga Centenary Celebrations (1905-2005) 77 References 79 List of Annexures Annexure-I: List of water birds recorded during 2005-2006 from Kaziranga National Park. -

Shukla Brochure 2019

Accommodation and other facilities Park Regulations to follow or There is one lodge and 10 home stay with 40 Beds operating just at the things to remember edge of park boundary near park headquarter. Other hotels are available in Mahendranagar. The Elephant camp (Hattisar) is located in Pipriya • An entry fee of Rs. 1,500 (Foreigners), Rs. 750 (SAARC Nationals) near the famous Mahakali suspension bridge and anybody can enjoy and Rs. 100 (Nepali) visitor should be paid at designated ticket for elephant riding. Blackbuck sighting and jungle driving facilities is counter per person per day. available in Arjuni check posts for the visitors. • Valid entry permits are available at entrance gate of ShNP. http//:www.dnpwc.gov.np Use of Park’s revenue • The entry permit is non-refundable, non-transferable and is for a single entry only. Website: 30-50 percent of the Park’s revenue goes directly to the Buffer Zone • Entering the park without a permit is illegal. Park personnel may | Communities for: ask for the permit, so visitors are requested to keep the permit • Biodiversity Conservation Programme with them. • Community Development • Get special permit for documentary/filming from the Department • Conservation Education of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation (DNPWC). • Income Generation and Skill Development ARK • Documentary/filming fee of US$ 1,500 (Foreigners), Rs. 50,000 [email protected] [email protected] P (SAARC Nationals) and Rs. 10,000 (Nepali) should be paid at Phone: +977-99-414309 How to Get Park DNPWC. Additional 25% should be paid while using drone for Email: The Park is accessible by road from any part of the country and documentary/filming. -

Bengal Florican Conservation Action Plan 2016-2020 BENGAL FLORICAN CONSERVATION ACTION PLAN 2016-2020

Bengal Florican Conservation Action Plan 2016-2020 BENGAL FLORICAN CONSERVATION ACTION PLAN 2016-2020 Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation a BENGAL FLORICAN CONSERVATION ACTION PLAN 2016-2020 Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation TECHNICAL TEAM Mr. Laxman Prasad Poudyal Dr. Naresh Subedi Dr. Kanchan Thapa Mr. Rishi Ranabhat Mr. Jyotendra Jyu Thakuri REVIEWER TEAM Mr. Krishna Prasad Acharya Dr. Maheshwar Dhakal Dr. Hem Sagar Baral Dr. Narendra Man Babu Pradhan Mr. Bijaya Raj Paudyal Dr. Paul Donald Mr. Ian Barber Copyright © Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, Babarmahal, Kathmandu, 2016. Waiver The materials of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for education or non-commercial uses, without permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for resale or other commercial purpose without prior permission of the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, Nepal. Citation DNPWC (2016) Bengal Florican Conservation Action Plan, Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, Kathmandu, Nepal. Cover Photo: Bengal Florican, Male © Bed Bahadur Khadka Foreword Nepal is rich in both faunal and floral biodiversity despites graded grassland and farmland leaves them vulnerable to its small size and terrain geography. The richness of bird further threats reducing their chances of survival. There- species is much higher than other species as the record fore, it is highly essential to develop an action plan of Ben- shows more than 878 bird species inhabits in Nepal from gal Florican and implement the conservation activities. -

Proposal for Inclusion of the Bengal Florican in Appendix I of The

CONVENTION ON UNEP/CMS/COP13/Doc. 27.1.5 MIGRATORY 25 September 2019 Original: English SPECIES 13th MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Gandhinagar, India, 17 - 22 February 2020 Agenda Item 27.1 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF THE BENGAL FLORICAN (Houbaropsis bengalensis bengalensis) IN APPENDIX I OF THE CONVENTION Summary: The Government of the Republic of India has submitted the attached proposal for the inclusion of the Bengal Florican (Houbaropsis bengalensis bengalensis) in Appendix I of CMS. The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CMS Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author PROPOSAL FOR INCLUSION IN CMS APPENDICES A. PROPOSAL To include the Bengal Florican Houbaropsis bengalensis bengalensis in the Appendix I of the Convention on Migratory Species B. PROPONENT India (Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change) C. SUPPORTING STATEMENT The Bengal Florican Houbaropsis bengalensis bengalensis, an iconic, critically endangered species of topmost conservation priority, exhibits transboundary movements, and its migration exposes it to threats such as land use changes, collision with power transmission line at boundary area of India-Nepal and probable power-line collisions. Inclusion of the species in Appendix I of CMS will aid in transboundary conservation efforts facilitated by International conservation bodies and existing international laws and agreement. 1. Taxonomy 1.1 Class - Aves 1.2 Order - Otidiformes 1.3 Family - Otididae 1.4 Genus, species or subspecies, including author and year -Bengal Florican Houbaropsis bengalensis(J.F. -

Rapid Decline of the Largest Remaining Population of Bengal Florican Houbaropsis Bengalensis and Recommendations for Its Conservation

Bird Conservation International (2013), page 1 of 9. © BirdLife International, 2013 doi:10.1017/S0959270913000567 Rapid decline of the largest remaining population of Bengal Florican Houbaropsis bengalensis and recommendations for its conservation C . E . P A C K M A N , D . A . S H O W L E R , N . J . C O L L A R , S O N V I R A K , S . P . M A H OOD , M. HANDSCHUH , T. D. EVANS , HONG CHAMNAN and P. M. DOLMAN Summary A census of the Critically Endangered Bengal Florican Houbaropsis bengalensis was conducted between March and May 2012 on and surrounding the Tonle Sap floodplain in Cambodia, which supports the last extant population of the Indochinese subspecies blandini . We found a decline in the number of displaying males of 44–64% since a comparable estimate from the same sites in 2005 to 2007. The estimated population, including five individuals at one previously unsurveyed site, is now 216 (95% CI 156–275) displaying males, plus potential non-displaying males and an unknown number of females. If numbers continue to be lost at a similar rate, it is possible that blandini would become extinct within 10 years. Although the population faces multiple threats, this critical situation has primarily been caused by the recent, rapid conversion of the florican’s grassland habitat to intensive, industrial-scale, irrigated rice cultivation. To protect the Bengal Florican from extinction in South East Asia, existing Bengal Florican Conservation Areas (BFCAs) need expansion and improvements, including strengthened legal status by prime ministerial sub- decree and better demarcation, patrolling and management.