Fluoxetine Effects on Molecular, Cellular and Behavioral Endophenotypes of Depression Are Driven by the Living Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

22 Psychiatric Medications for Monitoring in Primary Care

22 Psychiatric Medications for Monitoring in Primary Care Medication Warnings, Precautions, and Adverse Events Comments Class: SSRI Fluvoxamine Boxed Warnings: Suicidality Used much less than SSRIs in the group of eight Indications: Warnings and Precautions: Similar to other SSRIs medications for prescribing, probably because it has no Adult: OCD Adverse Events: Similar to other SSRIs FDA indication for MDD or any anxiety disorder. Still Child/Adolescent: OCD (10-17 years) somewhat popular as a medication for OCD. Uses: Anxiety, OCD Monitoring: Same as other SSRIs Citalopram Boxed Warning: Suicidality. Escitalopram, one of the SSRIs in the group of Indications: Warnings and Precautions: Similar to other SSRIs medications for prescribing, is an active metabolite of Adult: MDD Adverse Events: Similar to other SSRIs citalopram. Escitalopram reportedly has fewer AEs and Child/Adolescent: None less interaction with hepatic metabolic enzymes than Uses: Anxiety, MDD, OCD citalopram but is otherwise essentially identical. Citalopram offers no advantage other than price, as Monitoring: Same as other SSRIs escitalopram is branded until 2012. Paroxetine Boxed Warnings: Suicidality. Paroxetine used much less than the SSRIs for Indications: Warnings and Precautions: Similar to other SSRIs prescribing, probably because of its nonlinear kinetics. Adult: MDD, OCD, Panic Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Adverse Events: Similar to other SSRIs A study of children and adolescents showed doubling Disorder, Social Anxiety Disorder, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder the dose of paroxetine from 10 mg/day to 20 mg/day Child/Adolescent: None resulted in a 7-fold increase in blood levels (Findling et Uses: Anxiety, MDD, OCD al, 1999). Thus, once metabolic enzymes are saturated, paroxetine levels can increase dramatically with dose Monitoring: Same as other SSRIs increases and decrease dramatically with dose decreases, sometimes leading to adverse events. -

Drugs That Can Cause Delirium (Anticholinergic / Toxic Metabolites)

Drugs that can Cause Delirium (anticholinergic / toxic metabolites) Deliriants (drugs causing delirium) Prescription drugs . Central acting agents – Sedative hypnotics (e.g., benzodiazepines) – Anticonvulsants (e.g., barbiturates) – Antiparkinsonian agents (e.g., benztropine, trihexyphenidyl) . Analgesics – Narcotics (NB. meperidine*) – Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs* . Antihistamines (first generation, e.g., hydroxyzine) . Gastrointestinal agents – Antispasmodics – H2-blockers* . Antinauseants – Scopolamine – Dimenhydrinate . Antibiotics – Fluoroquinolones* . Psychotropic medications – Tricyclic antidepressants – Lithium* . Cardiac medications – Antiarrhythmics – Digitalis* – Antihypertensives (b-blockers, methyldopa) . Miscellaneous – Skeletal muscle relaxants – Steroids Over the counter medications and complementary/alternative medications . Antihistamines (NB. first generation) – diphenhydramine, chlorpheniramine). Antinauseants – dimenhydrinate, scopolamine . Liquid medications containing alcohol . Mandrake . Henbane . Jimson weed . Atropa belladonna extract * Requires adjustment in renal impairment. From: K Alagiakrishnan, C A Wiens. (2004). An approach to drug induced delirium in the elderly. Postgrad Med J, 80, 388–393. Delirium in the Older Person: A Medical Emergency. Island Health www.viha.ca/mhas/resources/delirium/ Drugs that can cause delirium. Reviewed: 8-2014 Some commonly used medications with moderate to high anticholinergic properties and alternative suggestions Type of medication Alternatives with less deliriogenic -

Headshop Highs & Lows

HeadshopHeadshop HighsHighs && LowsLows AA PresentationPresentation byby DrDr DesDes CorriganCorrigan HeadshopsHeadshops A.K.A.A.K.A. ““SmartSmart ShopsShops””,, ““HempHemp ShopsShops””,, ““HemporiaHemporia”” oror ““GrowshopsGrowshops”” RetailRetail oror OnlineOnline OutletsOutlets sellingselling PsychoactivePsychoactive Plants,Plants, ‘‘LegalLegal’’ && ““HerbalHerbal”” HighsHighs asas wellwell asas DrugDrug ParaphernaliaParaphernalia includingincluding CannabisCannabis growinggrowing equipment.equipment. Headshops supply Cannabis Paraphernalia HeadshopsHeadshops && SkunkSkunk--typetype (( HighHigh Strength)Strength) CannabisCannabis 1.1. SaleSale ofof SkunkSkunk--typetype seedsseeds 2.2. AdviceAdvice onon SinsemillaSinsemilla TechniqueTechnique 3.3. SaleSale ofof HydroponicsHydroponics && IntenseIntense LightingLighting .. CannabisCannabis PotencyPotency expressedexpressed asas %% THCTHC ContentContent ¾¾ IrelandIreland ¾¾ HerbHerb 6%6% HashHash 4%4% ¾¾ UKUK ¾¾ HerbHerb** 1212--18%18% HashHash 3.4%3.4% ¾¾ NetherlandsNetherlands ¾¾ HerbHerb** 20%20% HashHash 37%37% * Skunk-type SkunkSkunk--TypeType CannabisCannabis && PsychosisPsychosis ¾¾ComparedCompared toto HashHash smokingsmoking controlscontrols ¾¾ SkunkSkunk useuse -- 77 xx riskrisk ¾¾ DailyDaily SkunkSkunk useuse -- 1212 xx riskrisk ¾¾ DiDi FortiForti etet alal .. Br.Br. J.J. PsychiatryPsychiatry 20092009 CannabinoidsCannabinoids ¾¾ PhytoCannabinoidsPhytoCannabinoids-- onlyonly inin CannabisCannabis plantsplants ¾¾ EndocannabinoidsEndocannabinoids –– naturallynaturally occurringoccurring -

The Psychoactive Effects of Psychiatric Medication: the Elephant in the Room

Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 45 (5), 409–415, 2013 Published with license by Taylor & Francis ISSN: 0279-1072 print / 2159-9777 online DOI: 10.1080/02791072.2013.845328 The Psychoactive Effects of Psychiatric Medication: The Elephant in the Room Joanna Moncrieff, M.B.B.S.a; David Cohenb & Sally Porterc Abstract —The psychoactive effects of psychiatric medications have been obscured by the presump- tion that these medications have disease-specific actions. Exploiting the parallels with the psychoactive effects and uses of recreational substances helps to highlight the psychoactive properties of psychi- atric medications and their impact on people with psychiatric problems. We discuss how psychoactive effects produced by different drugs prescribed in psychiatric practice might modify various disturb- ing and distressing symptoms, and we also consider the costs of these psychoactive effects on the mental well-being of the user. We examine the issue of dependence, and the need for support for peo- ple wishing to withdraw from psychiatric medication. We consider how the reality of psychoactive effects undermines the idea that psychiatric drugs work by targeting underlying disease processes, since psychoactive effects can themselves directly modify mental and behavioral symptoms and thus affect the results of placebo-controlled trials. These effects and their impact also raise questions about the validity and importance of modern diagnosis systems. Extensive research is needed to clarify the range of acute and longer-term mental, behavioral, and physical effects induced by psychiatric drugs, both during and after consumption and withdrawal, to enable users and prescribers to exploit their psychoactive effects judiciously in a safe and more informed manner. -

Adverse Effects of First-Line Pharmacologic Treatments of Major Depression in Older Adults

Draft Comparative Effectiveness Review Number xx Adverse Effects of First-line Pharmacologic Treatments of Major Depression in Older Adults Prepared for: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20857 www.ahrq.gov This information is distributed solely for the purposes of predissemination peer review. It has not been formally disseminated by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The findings are subject to change based on the literature identified in the interim and peer-review/public comments and should not be referenced as definitive. It does not represent and should not be construed to represent an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or Department of Health and Human Services (AHRQ) determination or policy. Contract No. 290-2015-00012I Prepared by: Will be included in the final report Investigators: Will be included in the final report AHRQ Publication No. xx-EHCxxx <Month, Year> ii Purpose of the Review To assess adverse events of first-line antidepressants in the treatment of major depressive disorder in adults 65 years or older. Key Messages • Acute treatment (<12 weeks) with o Serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) (duloxetine, venlafaxine), but not selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (escitalopram, fluoxetine) led to a greater number of adverse events compared with placebo. o SSRIs (citalopram, escitalopram and fluoxetine) and SNRIs (duloxetine and venlafaxine) led to a greater number of patients withdrawing from studies due to adverse events compared with placebo o Details of the contributing adverse events in RCTs were rarely reported to more clearly characterize what adverse events to expect. -

Oomipramine Administered During the Luteal Phase Reduces the Symptoms of Premenstrual Syndrome: a Placebo-Controlled Trial Charlotta Sundblad, M.D., Marina A

NtUROPSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY 1993-VOL. 9, NO. 2 133 Oomipramine Administered during the Luteal Phase Reduces the Symptoms of Premenstrual Syndrome: A Placebo-Controlled Trial Charlotta Sundblad, M.D., Marina A. Hedberg, M.D., and Elias Eriksson, M.D., Ph.D. II.previous controlled trial we have shown that registered daily using a visual analogue scale) were pmntTIstrual irritability and depressed mood significantly reduced during treatment; in the placebo t,mnenstrual syndrome) can be effectively reduced by group, this symptom reduction was about 45%, whereas ...doses of the potent (but nonselective) serotonin in the clomipramine group it was greater than 70%. The nptakeinhi bitor clomipramine taken each day of the mean premenstrual ratings of irritability and depressed f/tIIStrualcycle. The present study was undertaken to mood during the three treatment cycles were significantly GIIfIine to what extent intermittent administration of lower in the clomipramine group than in the placebo dDmipramine, during the luteal phase only, is also group. Also with respect to the rating of global Iftdiveagainst premenstrual complaints. Twenty-nine improvement, the result obtained with clomipramine was ..dtpressed women displaying severe premenstrual significantly better than that obtained with placebo. The iriMbility and/or depressed mood and fulfilling the study confirms the previously reported effectiveness of DSM·/ll·R criteria of late luteal phase dysphoric disorder low doses of clomipramine in the treatment of IrIr treateddaily from the day of ovulation until the premenstrual syndrome and demonstrates that the time .nof the menstruation either with clomipramine (25 lag between onset of medication and clinical effect is � 7Smg) (n = 15) or with placebo (n = 14) for three shorter when clomipramine is used for premenstrual III/StCUtive menstrual cycles; another nine subjects (seven syndrome than when it is used for depression, panic • cIomipramine, two on placebo) dropped out during disorder, or obsessive compulsive disorder. -

Frequently Asked Questions About Antidepressant Medications

Frequently Asked Questions about Antidepressant Medications How do antidepressant medications work? Antidepressants affect the balance of chemicals in the brain that affect mood. These are called neurotransmitters. However, research has not clarified exactly how antidepressants work. Are antidepressants addictive? No. They are not habit – forming and do not produce a “high.” Once you reach a dose that works for you, you do not require ever increasing doses to maintain the beneficial effect. Will I get better if I take an antidepressant? Antidepressant medications are proven to improve mood for most people with moderate or severe depression. Combining antidepressant medication with psychotherapy is even more effective. For mild depression, many people may improve with supportive counseling and active follow up from their primary care physician. If mild depression persists, then antidepressant medication and / or psychotherapy are usually effective. For all levels of depression, healthy lifestyle is important. This include eating healthy foods, sleeping and exercising regularly, engaging in pleasurable activities, using stress reduction techniques, and sharing your thoughts and concerns with supportive friends or family. How long will it take for the antidepressant medication to work? People usually start to feel better two to four weeks after starting an antidepressant. Sleep and appetite may improve first, but it may take longer for your mood and energy to improve. If your depression is not improved after a few weeks, your doctor may suggest adding psychotherapy (if you are not already doing this), increasing the dose or switching to another medication. Are there any side effects from antidepressants? Side effects are usually mild. -

Depression and Anxiety Pharmacological Treatment in General Practice

THEME Mental health Depression and anxiety Pharmacological treatment in general practice BACKGROUND Depression and anxiety are common presentations in general practice and medications are one of the key treatment strategies. OBJECTIVE This article provides an overview of important practical issues to consider when prescribing medications for anxiety and depression. Steven Ellen MBBS, MMed(Psych), DISCUSSION MD, FRANZCP, is Head, Key questions for the general practitioner to consider are: Consultation-Liaison • Are medications the best option? Psychiatry, The Alfred Hospital, • Which is the best medication for this patient? Melbourne, Victoria. s.ellen@ alfred.org.au • What are the practical aspects of prescribing this medication? • What is the next step if it doesn’t work? Rob Selzer MBBS, PhD, FRACP, FRANZCP, is Consultant Psychiatrist, Primary Mental Health & Early General practitioners are the main providers symptom of other disorders such as physical illness. From Intervention Team, The Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, Victoria. of treatment for anxiety and depression in our a prescribing point of view, separating depression from community and medications are often prescribed anxiety and vice versa, is less crucial as they often occur Trevor Norman as part of the treatment plan. The BEACH study together, and the pharmacological first line for both is often BSc, PhD, is Associate Professor, Department of (Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health Program)1 the same (an antidepressant). Psychiatry, University of showed that GPs treat psychological problems at a Following diagnosis, the next important issue is the Melbourne, Austin Hospital, rate of 11.5 per 100 encounters, and medications are patient’s attitude to medication. What are their preferences Heidelberg, Victoria. -

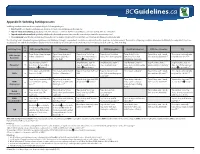

Appendix D: Switching Antidepressants Switching Antidepressants Can Be Accomplished by the Following Strategies: 1

Appendix D: Switching Antidepressants Switching antidepressants can be accomplished by the following strategies: 1. Direct switch: stop the first antidepressant abruptly and start new antidepressant the next day. 2. Taper & switch immediately: gradually taper the first antidepressant, then start the new antidepressant immediately after discontinuation. 3. Taper & switch after a washout: gradually withdraw the first antidepressant, then start the new antidepressant after a washout period. 4. Cross-tapering: taper the first antidepressant (usually over 1-2 week or longer), and build up the dose of the new antidepressant simultaneously. The following table is intended for general guidance only. Whichever strategy is used, patients should be closely monitored for symptoms and adverse events. The duration of tapering should be determined individually for each patient. Physicians should balance the risk of discontinuation symptoms versus risk of delay in new treatment. The washout period is mostly dependent on the t1/2 of the first drug. To Switching From ➞ SSRIs (except fluoxetine) Fluoxetine SNRIs NDRI (bupropion) NaSSA (mirtazapine) RIMA (moclobemide) TCA Taper & stop, then start new Taper & stop, then start Taper & stop5 (or to low Taper & stop5 (or to low Taper & stop5 (or to Taper & stop, wait 1 week, Cross-taper cautiously with SSRIs (except ➞ SSRI at a low dose1,† fluoxetine at low dose dose),1 then start low dose dose),2 then start bupropion. low dose),1 then start then start moclobemide.1,5 very low dose TCA.1,3,5,‡,§ fluoxetine) (10 mg daily)1,† SNRI & very slowly.1,3,5,† mirtazapine cautiously. Stop fluoxetine, wait 4-7 Stop fluoxetine, wait 4-7 Stop fluoxetine, wait 4-7 Stop fluoxetine, wait 4-7 Stop fluoxetine, wait 5 Stop fluoxetine, wait 4-7 Fluoxetine* ➞ days. -

Antidepressant- and Anxiolytic Effects of the Novel Melatonin Agonist Neu-P11 in Rodent Models

Acta Pharmacologica Sinica (2010) 31: 775–783 npg © 2010 CPS and SIMM All rights reserved 1671-4083/10 $32.00 www.nature.com/aps Original Article Antidepressant- and anxiolytic effects of the novel melatonin agonist Neu-P11 in rodent models Shao-wen TIAN1, #, *, Moshe LAUDON2, #, Li HAN1, 3, Jun GAO1, Fu-lian HUANG1, Yu-feng YANG1, Hai-feng DENG1 1Department of Physiology, Medical School, University of South China, Hengyang 421001, China; 2Neurim Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Tel- Aviv, Israel; 3Department of Physiology, Changsha Medical University, Changsha 410219, China Aim: To investigate the potential antidepressant and anxiolytic effects of Neu-P11, a novel melatonin agonist, in two models of depression in rats and a model of anxiety in mice. Methods: In the learned helplessness test (LH), Neu-P11 or melatonin (25–100 mg/kg, ip) was administered to rats 2 h before the beginning of the dark phase once a day for 5 days and the number of escape failures and intertrial crossings during the test phase were recorded. In the forced swimming test (FST), rats received a single or repeated administration of Neu-P11 (25–100 mg/kg, ip). The total period of immobility during the test phase was assessed. In the elevated plus-maze test (EPM), mice were treated with Neu- P11 (25–100 mg/kg, ip) or melatonin in the morning or in the evening and tested 2 h later. The percentage of time spent in the open arms and the open arms entries were assessed. Results: In the LH test, Neu-P11 but not melatonin significantly decreased the escape deficit and had no effect on the intertrial cross- ings. -

At-A-Glance: Psychotropic Drug Information for Children and Adolescents

At-A-Glance: Psychotropic Drug Information for Children and Adolescents Pediatric Dosage/ Drug Generic FDA Approval Serum Level Name Age/Indication when applicable Warnings and Precautions/Black Box Warnings Combination Antipsychotic/Antidepressant fluoxetine & 18 and older N/A: Pediatric Black Box Warning for fluoxetine/olanzapine olanzapine dosing is currently combination formula (marketed as Symbyax): Usage unavailable or not increased the risk of suicidal thinking and behaviors in applicable for this children and adolescents with major depressive disorder drug. and other psychiatric disorders. Other precautions for fluoxetine/olanzapine combination: Possibly unsafe during lactation. Avoid abrupt withdrawal. Antipsychotic Medications *Precautions which apply to all atypical or second generation antipsychotics (SGA): Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome/Tardive Dyskinesia/ Hyperglycemia/ Diabetes Mellitus/ Weight Gain/ Akathisia/Dyslipidemia †Precautions which apply to all typical or first generation antipsychotics (FGA): Extrapyramidal symptoms/Tardive Dyskinesia aripiprazole * (SGA) 10 and older for 2-10 mg/kg/day Black Box Warning for aripiprazole: Not approved for bipolar disorder, depression in under age 18. Increased risk of suicidal manic, or mixed thinking and behavior in short-term studies in children episodes; 13 to 17 and adolescents with major depressive disorder and for schizophrenia other psychiatric conditions. and bipolar; 6 to 17 for irritability associated with autistic disorder asenapine* 18 and older N/A Black Box Warning for asenapine: Not approved for dementia-related psychosis. Increased mortality risk for elderly dementia patients due to cardiovascular or infectious events. chlorpromazine† 18 and older 0.25 mg/kg tid Other precautions for chlorpromazine: May alter cardiac (FGA) conduction; sedation; Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome; weight gain. Use caution with renal disease, seizure disorders, and respiratory disease and in acute illness. -

Medication Guide Antidepressant Medicines, Depression and Other Serious Mental Illnesses, and Suicidal Thoughts Or Actions

Medication Guide Antidepressant Medicines, Depression and other Serious Mental Illnesses, and Suicidal Thoughts or Actions Read the Medication Guide that comes with you or your family member’s antidepressant medicine. This Medication Guide is only about the risk of suicidal thoughts and actions with antidepressant medicines. Talk to your, or your family member’s, healthcare provider about: • all risks and benefits of treatment with antidepressant medicines • all treatment choices for depression or other serious mental illness What is the most important information I should know about antidepressant medicines, depression and other serious mental illnesses, and suicidal thoughts or actions? 1. Antidepressant medicines may increase suicidal thoughts or actions in some children, teenagers, and young adults within the first few months of treatment. 2. Depression and other serious mental illnesses are the most important causes of suicidal thoughts and actions. Some people may have a particularly high risk of having suicidal thoughts or actions. These include people who have (or have a family history of) bipolar illness (also called manic-depressive illness) or suicidal thoughts or actions. 3. How can I watch for and try to prevent suicidal thoughts and actions in myself or a family member? • Pay close attention to any changes, especially sudden changes, in mood, behaviors, thoughts, or feelings. This is very important when an antidepressant medicine is started or when the dose is changed. • Call the healthcare provider right away to report new or sudden changes in mood, behavior, thoughts, or feelings. • Keep all follow-up visits with the healthcare provider as scheduled. Call the healthcare provider between visits as needed, especially if you have concerns about symptoms.