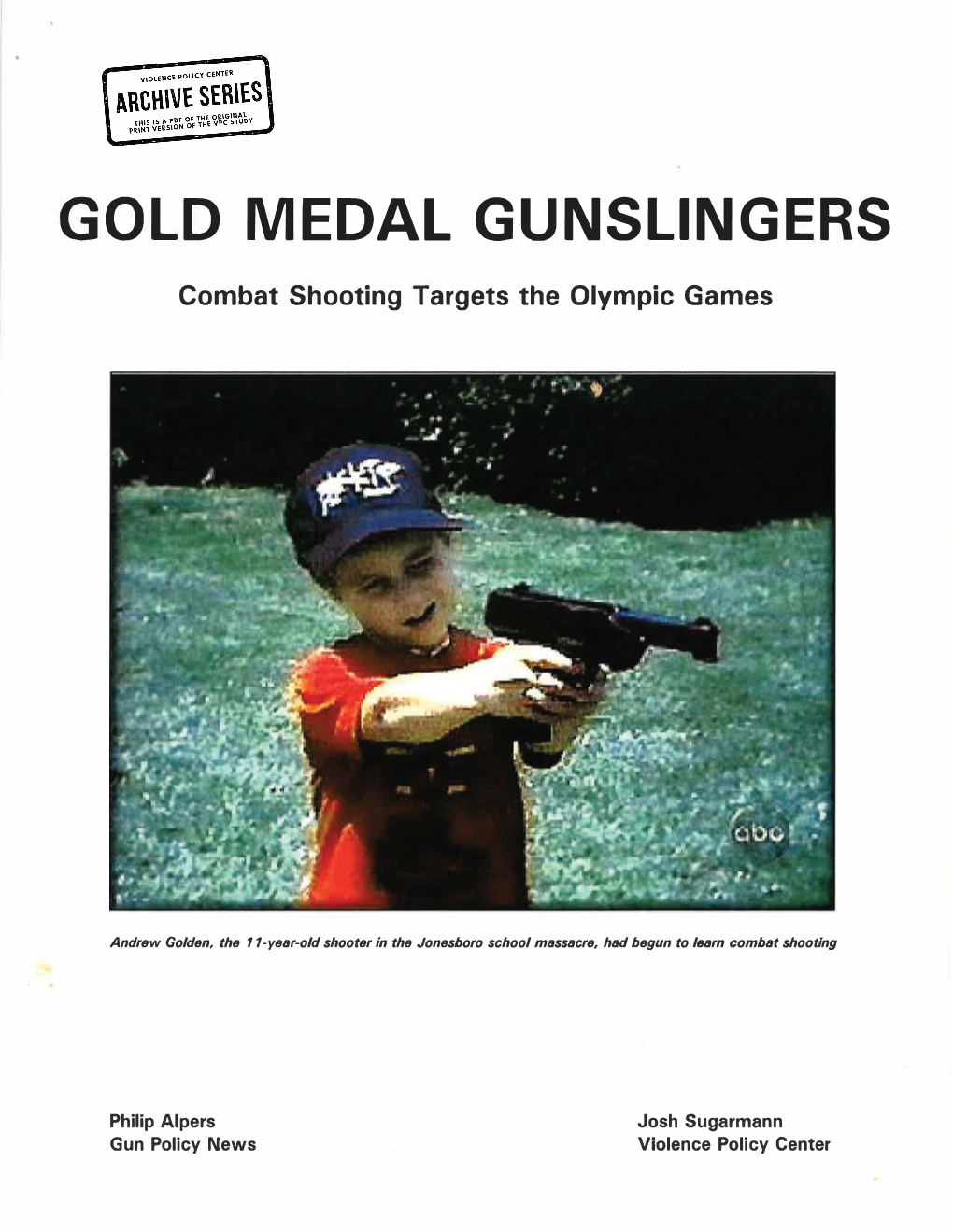

Gold Medal Gunslingers: Combat Shooting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURES Revision 10.0

STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURES Revision 10.0 Effective: November 10, 2020 Contents GTGC ADMINISTRATIVE ITEMS ............................................................................................................................................... 2 GTGC BOARD OF DIRECTORS: ............................................................................................................................................. 2 GTGC CHIEF RANGE SAFETY OFFICERS: ............................................................................................................................... 2 CLUB PHYSICAL ADDRESS: ................................................................................................................................................... 2 CLUB MAILING ADDRESS: .................................................................................................................................................... 2 CLUB CONTACT PHONE NUMBER ....................................................................................................................................... 2 CLUB EMAIL ADDRESS: ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 CLUB WEB SITE: ................................................................................................................................................................... 2 HOURS OF OPERATION ...................................................................................................................................................... -

National Rifle Association the Nra Handbook

NATIONAL RIFLE ASSOCIATION THE NRA HANDBOOK Including the NRA RULES OF SHOOTING and the Programme of THE IMPERIAL MEETING FRIDAY 12 JUNE TO SATURDAY 25 JULY 2020 This Handbook is issued by, and the Rules, Regulations and Conditions are made by, order of the Council and approved on 22 February 2020. This document is effective from 30 March 2020. Published by the National Rifle Association, Bisley Camp, Brookwood, Woking, Surrey, GU24 0PB Tel: 01483 797777 Fax: 01483 797285 £9.50 10 11 THE HANDBOOK OF THE NATIONAL RIFLE ASSOCIATION This book contains three Volumes, each containing Parts, Sections and Paragraphs. Appendices appear at the end of each Volume. Parts, Sections, Paragraphs and Appendices are all numbered consecutively through the entire book. To avoid repeating pronouns, the masculine form only is used throughout. Thus ‘he’ should be read as ‘he/she’, ‘him’ as ‘him/her’, and ‘his’ as ‘his/her(s)’. The 24 hour clock is used throughout. Volumes 4 to 6, the NRA Gallery Rifle and Pistol Handbook, the NRA Target Shotgun Handbook and the NRA Civilian Service Rifle and Practical Rifle Handbook, are published separately, but derive authority from the Council’s authorisation of this Handbook. Volume 7, the Classic and Historic Arms Handbook, is in preparation. This book is available in large print on A4 paper by application to Shooting Division. All Volumes of the Handbook are available as pdf downloads on the NRA website. Information contained in this Handbook is valid as at 22 February 2020. Changes will be notified via the NRA website, the NRA Journal and, if necessary, by e-mail and/or post. -

International Practical Shooting Confederation

INTERNATIONAL PRACTICAL SHOOTING CONFEDERATION REGLAMENTO PARA COMPETENCIAS DE ARMA CORTA EDICION DE ENERO 2004 International Practical Shooting Confederation PO Box 972, Oakville, Ontario Canada L6J 9Z9 Tel: +1 905 849 6960 Fax: +1 905 842 4323 Email: [email protected] Web: www.ipsc.org Traducido al español por José L. Beltrami (IPSC Uruguay) Revisado por Victor Ferrero (IPSC Ecuador) Copyright © 2003 International Practical Shooting Confederation Copyright © 2004 José L. Beltrami <[email protected]> Índice General Capítulo 1 - Diseño de etapas 1.1 Principios generales ................................................................................................................................................. 7 1.1.1 Seguridad ................................................................................................................................................. 7 1.1.2 Calidad ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1.3 Balance ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1.4 Diversidad ................................................................................................................................................ 7 1.1.5 Estilo libre ................................................................................................................................................ 7 1.1.6 Dificultad -

INTERNATIONAL PRACTICAL SHOOTING CONFEDERATION Minutes of the Thirtieth General Assembly Kavala, Greece, 9:00 Am Monday, 4 September 2006

INTERNATIONAL PRACTICAL SHOOTING CONFEDERATION Minutes of the Thirtieth General Assembly Kavala, Greece, 9:00 am Monday, 4 September 2006 ADMINISTRATION 1) IPSC Secretary to present a list of voting Regions and proxies Executive Council Present: IPSC President Mr. Nick Alexakos IPSC General Secretary Mr. Fritz Gepperth IPSC Secretary Mr. Vince Pinto IPSC Treasurer Mr. Ren Henderson IROA President Mr. Dino Evangelinos IROA Vice-president Mr. Juergen Tegge Regions Present: 21 Australia Mr. Des Lilley Belgium Mr. Yvan Vogels Czech Republic Mr. Josef Horejsi Denmark Mr. Tim Andersen Ecuador Mr. Victor Ferrero Finland Mr. Timo McKeown France Mr. Alain Joly Germany Mr. Fritz Gepperth Greece Mr. Dimitrios Tzimas Hong Kong Mr. Vince Pinto (alternate) Israel Mr. Nachum Zarzif Italy Mr. Riccardo Massantini Netherlands Mr. Kees Guichelaar Norway Mr. Geir Owe Philippines Mr. Rey Ganaban (alternate) Russia Mr. Vitaly Kryushin Slovak Republic Mr. Damjian Pesek South Africa Mr. Daan Kemp Switzerland Mr. Milan Stojanovic Thailand Mr. Peter Walker (alternate) United Kingdom Mr. Graham Gill Voting Regions: (36) The following Regions were eligible to vote and were either present at the meeting or submitted a valid proxy form, as indicated by italics: Argentina Aruba Australia Austria Belgium Brazil Canada Czech Republic Denmark Ecuador Finland France Germany Greece Hong Kong Hungary Indonesia Israel Italy Macau Malta Netherlands New Zealand Norway Papua New Guinea Philippines Russia Singapore Slovenia South Africa Switzerland Thailand United Kingdom United States Venezuela Zimbabwe 2) IPSC President to appoint two tellers Mr. Myro Lopez (PHI) Mr. Joey Racaza (PHI) 3) IPSC Executive Council Reports Individual verbal reports were given by each Executive Council member. -

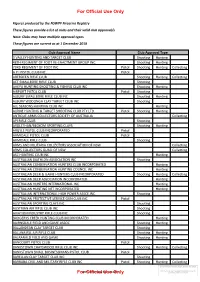

5842:ED Use - PAGE Only 1 Command, NSW Police Force

For Official Use Only Figures produced by the NSWPF Firearms Registry These figures provide a list of clubs and their valid club approval/s Note: Clubs may have multiple approval types These figures are current as at 1 December 2018 Club Approval Name Club Approval Type 3 VALLEY HUNTING AND TARGET CLUB Shooting Hunting 48TH REGIMENT OF FOOT RE-ENACTMENT GROUP INC. Shooting Hunting 73RD REGIMENT OF FOOT INC Pistol Shooting Hunting Collecting A P I PISTOL CLUB INC. Pistol ABERDEEN RIFLE CLUB Shooting Hunting Collecting ACT SMALLBORE RIFLE CLUB Shooting AHEPA HUNTING SHOOTING & FISHING CLUB INC Shooting Hunting AIRPORT PISTOL CLUB Pistol Shooting ALBURY SMALLBORE RIFLE CLUB INC Shooting Hunting ALBURY WODONGA CLAY TARGET CLUB INC Shooting ALL SEASONS HUNTING CLUB INC Hunting ALPINE HUNTING & TARGET SHOOTING CLUB PTY LTD Pistol Shooting Hunting ANTIQUE ARMS COLLECTORS SOCIETY OF AUSTRALIA Collecting API RIFLE CLUB Shooting ARDLETHAN/BECKOM SPORTING CLAYS Shooting Hunting ARGYLE PISTOL CLUB INCORPORATED Pistol ARMIDALE PISTOL CLUB Pistol ARMIDALE RIFLE CLUB Shooting ARMS AND MILITARIA COLLECTORS'ASSOCIATION OF NSW Collecting ARMS COLLECTORS GUILD OF NSW Collecting ASC HUNTING CLUB INC Hunting AUSTRALIAN BIATHLON ASSOCIATION INC Shooting AUSTRALIAN CONSERVATION HUNTERS CLUB INCORPORATED Hunting AUSTRALIAN CONSERVATION HUNTING COUNCIL INC Hunting AUSTRALIAN DEER & GAME HUNTERS CLUB INCORPORATED Shooting Hunting Collecting AUSTRALIAN DEER ASSOCIATION INCORPORATED Hunting AUSTRALIAN HUNTERS INTERNATIONAL INC Hunting AUSTRALIAN HUNTING NET INCORPORATED -

INTERNATIONAL PRACTICAL SHOOTING CONFEDERATION Minutes of the 40Th IPSC General Assembly Hotel Eger, Hungary, Saturday 1 October 2016, 9:00 Am

INTERNATIONAL PRACTICAL SHOOTING CONFEDERATION Minutes of the 40th IPSC General Assembly Hotel Eger, Hungary, Saturday 1 October 2016, 9:00 am ADMINISTRATION Executive Council Present: IPSC President Mr. Nick Alexakos IPSC Gen. Secretary Mr. Alain Joly IPSC Treasurer Mr. Ren Henderson IPSC Secretary Mr. Dimitrios Tzimas IROA President Mr. Dino Evangelinos IROA Vice-President Mr. Juergen Tegge 1) IPSC Secretary to present a list of voting Regions and proxies Regions represented (voting and non-voting): 33 Australia Mr. Gareth Graham Austria Mr. Mario Kneringer Brazil Mr. Demetrius Da Silva Oliveira Bulgaria Mr. Krasimir Petrov Mihtiev Czech Republic Mr. Roman Sedy Denmark Mr. Tim Andersen Estonia Mr. Jaanus Viirlo (D) Finland Mr. Mikael Ekberg France Mr. Stephane Quertinier Germany Mr. Fritz Gepperth Great Britain Mr. Kevin Strowger Hungary Mr. Karoly Krizsan Ireland Mr. Andrew Pedlow Isle Of Man Mr. Geoff Mitchell Israel Mr. Nachum J. Zarzif Italy Mr. Luca Zolla Latvia Mr. Stanislav Sheiko Lithuania Mr. Linas Karosas Netherlands Mr. Sasja Barentsen Northern Ireland Mr. Cleland Rogers Norway Mr. Kyrre Lee Romania Dr. Jimmy R. Barbutti Russia Mr. Vitaly Kryuchin Serbia Mr. Spasoje Vulevic Slovak Republic Mrs. Janette Haviarova Slovenia Mr. Robert Cernigoj South Africa Mrs. Chrissie Wessels (D) Sweden Mr. Roland Dahlman Switzerland Mr. Alain Arnold (D) Ukraine Mr. Alexander Milyukov United Arab Emirates Mr. Salem Al Matrooshi United States Mr. Matt Hopkins (D) Zimbabwe Mrs. Chrissie Wessels (D) Voting Regions – Delegate or proxy: 59 Regions voting by delegate (30): Australia, Austria, Brazil, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Great Britain, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Lithuania, Netherlands, Northern Ireland, Norway, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, South Africa, Sweden, Switzerland, Ukraine, United States, Zimbabwe. -

Long Term Development

Long Term Development Target Shooting: a lifetime sport Copyright: Shooting Federation of Canada, 2021 Table of Contents 2 Acknowledgements 3 Foreword 4 Target Shooting is unique 4 Becoming involved in Target Shooting 5 The disciplines of Olympic Target Shooting 6 Target Shooting for athletes with a physical disability 8 Use of Firearms 8 Environmental Concerns 9 Why is LTD important for Target Shooting? 10 Current status of Target Shooting sports in Canada 11 The factors influencing LTD 15 The Stages of Long Term Development for Target Shooting 16 • Active Start 17 • FUNdamentals 18 • Learn to Shoot 19 • Train to Train 20 • Train to Compete 21 • Train to Win 22 • Active for Life: Target Shooting is a lifetime sport 24 Appendices 24 1. Glossary of Terms 26 2. Development of Mental Skills 30 3. Resource List 31 4. LTD Steering Committee LONG TERM DEVELOPMENT 1 Acknowledgements Shooting Federation of Canada (SFC) LTD Steering Committee: Bernie Harrison Istvan Balyi (LTD Expert Group) Mo Johnson Cathy Haines (Consultant) Rick Ward Susan Verdier (SFC Technical Director) The SFC acknowledges the contribution of the following individuals in the preparation of this document: Mike LaRochelle Keith Stieb Reg Potter Curtis Wennberg We also wish to thank the Federation of Canadian Archers, Biathlon Canada and the Canadian Fencing Federation for being role models with their Long Term Development framework documents, and for allowing us the use of some of their materials and ideas. 2 LONG TERM DEVELOPMENT Foreword The SFC has created this Long Term Development framework as a model for the development of athletes in the Target Shooting sports. -

Smallbore Rifle

January 2021 www.ssusa.org Coming Events NRA SANCTIONED TOURNAMENTS To be listed, NRA must sanction matches by the 15th of the month, two months prior to the month of the magazine issue. If you are interested in entering a tournament, contact the individual listed. For any cancellations or changes to this listing, please contact Shelly Kramer: [email protected], NRA Competitive Shooting Division. 1 January 2021 www.ssusa.org Legend A: NRA Approved Tournament OAR: Open Air Rifle R: NRA Registered Tournament OF: Offhand 1800: 1800-pt. match OP: Open 2700: 2700-pt. match ORF: Open Rimfire 3200: 3200-pt. match OS: Open Sights 6400: 6400-pt. match OUT: Outdoor 3P: 3-Position PAL: Palma 4P: 4-Position PC: Pistol Cartridge Lever Action Silh AIR: Air Pistol PI: Pistol AP: Action Pistol POS: Position BP: Black Powder POST: Postal BPS: Black Powder Scope PPC: Police Pistol Combat CFP: Center-Fire Pistol PRE: Precision CON: Conventional PRN: Prone CC: Creedmoor Cup PRO: Production DR: Distinguished Revolver PRF: Production Rimfire FC: F-Class RF: Rimfire FRP: Free Pistol RFP: Rapid-Fire Pistol FBP: Fullbore Prone SAR: Sporter Air Rifle HPR: High Power SBHP: Smallbore Hunter’s Pistol HPHR: High Power Hunting Rifle SBHR: Smallbore Hunting Rifle HPSR: High Power Sporting Rifle SBR: Smallbore Rifle HPSA: High Power Semi-Auto SC: Short Course HP: Hunter’s Pistol SO: Scope Only IN: Indoor SCLA: Smallbore Lever Action Silh Rifle IND: Individual SER: Service INSER: Interservice SP: Service Pistol INV: Invitational SPI: Sport Pistol ISO: Iron Sight Only SPT: Sporter JR: Junior SR: Service Rifle LA: Lever Action Silh Rifle STA: Standing LM: Leg Match STD: Standard LR: Long-Range STK: Stock Gun LTR: Light Rifle TAR: Target MET: Meters TM: Team MR: Mid-Range USTA: Unlimited Standing MRP: Mid-Range Prone WSP: Women’s Sport Pistol MS: Metallic Sights YD: Yards 2 January 2021 www.ssusa.org Table of Contents (Click the Left Mouse button to jump to a section) PISTOL ..................................................................... -

Download Product Catalog

V6 HEADQUARTERS STAFFORD, TX SRT FABRICATION SUGAR LAND, TX ABOUT US Laser Shot provides affordable, alternative training solutions for military, ODZHQIRUFHPHQWSURIHVVLRQDOVDQGSURVKRRWHUV6LQFHLWVHVWDEOLVKPHQWLQ /DVHU6KRWKDVUHPDLQHGFRPPLWWHGWRGHYHORSLQJWKHPRVWUHDOLVWLF DQG SUDFWLFDO ¿UHDUP VLPXODWRUV FUHZ WUDLQLQJ VLPXODWRUV DQG OLYH¿UH Laser Shot, Inc. IDFLOLWLHVDYDLODEOHZRUOGZLGH &RUSRUDWH2I¿FH 4214 Bluebonnet Drive Stafford, Texas 77477 /DVHU 6KRW RIIHUV SURJUHVVLYH WUDLQLQJ VROXWLRQV WKDW DUH DSSOLFDEOH WR Phone: 281.240.1122 DOOVNLOOOHYHOVDGDSWDEOHIRULQGLYLGXDOFXVWRPHUQHHGV²DOOZKLOHIRFXVLQJ RQ ³WUDLQDV\RX¿JKW´ FRUH SULQFLSOHV 2XU WUDLQLQJ VROXWLRQV DXJPHQW H[LVWLQJ SURJUDPV ZLWK VDIH DOWHUQDWLYHV E\ XVLQJ WHFKQRORJLFDOO\ DGYDQFHG VLPXODWLRQV IRU LPPHUVLYH WUDLQLQJ ,Q OLYH¿UH IDFLOLWLHV WKH\ WXUQ FRQYHQWLRQDO PXQGDQH UDQJHV DQG VKRRW KRXVHV LQWR H[FHSWLRQDO FXWWLQJHGJHIDFLOLWLHV v10.5 SRT FABRICATION SUGAR LAND, TX CONTENTS SYSTEMS 06 TRAINING SOFTWARE 12 SIMULATED FIREARMS 29 ACCESSORIES 36 Shooting Range Technologies (SRT) )DEULFDWLRQ 730 Sartartia Rd RANGES 38 Sugar Land, Texas 77479 Phone: 281.240.1122 TECHNOLOGY 6LQFH/DVHU6KRWKDVUHVHDUFKHGFDPHUDWHFKQRORJ\WR¿QGDQRSWLPXPPHWKRGIRUWUDFNLQJVLPXODWHG¿UHDUPVXVLQJ YLVLEOHDQGLQIUDUHGODVHUV/DVHU6KRWFDPHUDVDUHWUXO\VWDWHRIWKHDUW:KHQFRPELQHGZLWK/DVHU6KRW¶VSURSULHWDU\VXESL[HO ODVHUWUDFNLQJDOJRULWKPWKHHQGUHVXOWLVWKHIDVWHVWDQGPRVWDFFXUDWHWUDFNLQJPHWKRGDYDLODEOHIRUVLPXODWHG¿UHDUPVRQWKH market today. /DVHU6KRW¶VFDPHUDWHFKQRORJ\LVDQLQWHJUDOSLHFHRIODUJHVFDOHPLOLWDU\WUDLQLQJVLPXODWRUVFXUUHQWO\LQXVHWKURXJKRXWWKH -

Integrated Management of Target Shooting Scoping Proposed Action 1

INTEGREATED MANAGEMENT OF TARGET SHOOTING ON THE PIKE NATIONAL FOREST Proposed Action for Public Scoping, January 2021 Background The Pike National Forest (the Forest), part of the Pike and San Isabel National Forests Cimarron and Comanche National Grasslands, is located in central Colorado, stretching north from Pikes Peak to Mount Evans, and west to the Continental Divide past the town of Fairplay (Figure 1). Given the Forest includes part of the Colorado Front Range adjacent to the two most populous centers in the state (the Denver metro area and Colorado Springs), much of this "urban" forest experiences heavy recreational use. In recent years, overall recreation use levels have increased in line with the population growth of the Colorado Front Range urban corridor. The US Census Bureau estimates the populations of Colorado, the Denver metro area, and the city of Colorado Springs grew by eight to ten percent in the five years between 2011 and 2016 (US Census Bureau, 2019). The combined population of the Denver metro area and Colorado Springs, both areas within a one-hour drive of the Pike National Forest, are estimated to have grown from over 3,263,400 in 2011 to over 3,570,500 in 2016 (ibid). The USDA Forest Service National Visitor Use Monitoring program estimates that annual visitation to the Pike and San Isabel National Forests (the smallest unit of measure available) increased five percent in the same period, from 4,281,000 site visits per year in 2011 to 4,502,000 site visits per year in 2016 (the last year data is available) (USDA Forest Service 2011, 2016). -

2019 Brookings County 4-H Shooting Sports Schedule

2019 Brookings County 4-H Shooting Sports Schedule Archery - 90 min BB Gun - 60 min Air Pistol - 60 min Air Rifle - 60 min .22 Rifle - 90 min .22 Pistol - 60 min Saturday Saturday Saturday Saturday Saturday Saturday 8:00 am 8:00 am 8:00 am 8:00 am 9:30 am 8:00 am 10:10 am 9:05 am 9:05 am 9:05 am 11:00 am 10:10 am 10:10 am 10:10 am Sunday Tuesday Sunday 11:15 am 11:15 am 3:00 pm 6:00 pm 5:15 pm All 4-H Shooting Sports disciplines will be held in Brookings at the Brookings County Outdoor Adventure Center; 2810 22nd Ave South SD 4-H Shooting Sports Website Link: www.sd4-hss.com sign up state time after qualified match score Brookings County 4-H Shooting Sports Page: https://www.facebook.com/brookings4hshootingsports Brookings County 4-H: https://www.facebook.com/brookings4H Cancellation Policy: If advising no travel in Brookings County then there will be no Shooting Sports. We will also list on KELO Closeline www.keloland.com/weather/closeline.cfm and Brookings County 4-H Shooting Sports Facebook page for the cancellation. There are many practice dates so use your best judgment if conditions are questionable in your area. Coaches will also use the Remind app for communicating reminders and schedule changes. Date Event Remember: November 19 – Online Registration Open: Payment is due to the Brookings County Extension/4-H December 2 https://fairentry.com/Fair/SignIn/2599 Office by 5 pm on December 7 or spots will be released. -

The Art of Shooting by Prof. Phillip Treleaven

Art of Shooting Art of Shooting An introduction to target shooting with rifle, pistol, shotgun and airgun Prof. Philip Treleaven Preface This handbook is a ‘primer’ for the new target shooter: introducing the firearms, shooting disciplines and firearm technology, and drawing on the expertise of Bisley, the home of British and Commonwealth target shooting. For someone interested in taking up target shooting, it is surprisingly difficult to find out what are the different shooting disciplines (or to give them their ISSF name Events), and perhaps more importantly what’s available in their area. Naturally you won’t find Shooting for Dummies in the local bookshop, but there are some excellent books and web sites, especially in the United States. Most cater for the experienced competitor in a specific discipline, like Smallbore or Benchrest, rather than the new shooter. I am fortunate in that I live 40 minutes drive from the world famous Bisley Camp, the home of British and Commonwealth shooting (cf. Camp Perry in America). The great thing about shooting at Bisley is the wealth of knowledge and experience available covering all aspects of the sport. People who have shot in the Olympics and Commonwealth Games, national champions for every shooting discipline, experts in ballistics and hand loading, gunsmiths and armourers … and national coaches. Truly a university of shooting – akin to Cambridge or Harvard! However, even at Bisley it is a daunting challenge to find out what shooting disciplines are available, and who to ask for advice. It’s like everyone else in the shooting world knows everything about shooting, marksmanship, ballistics and hand loading, and you the novice know nothing.