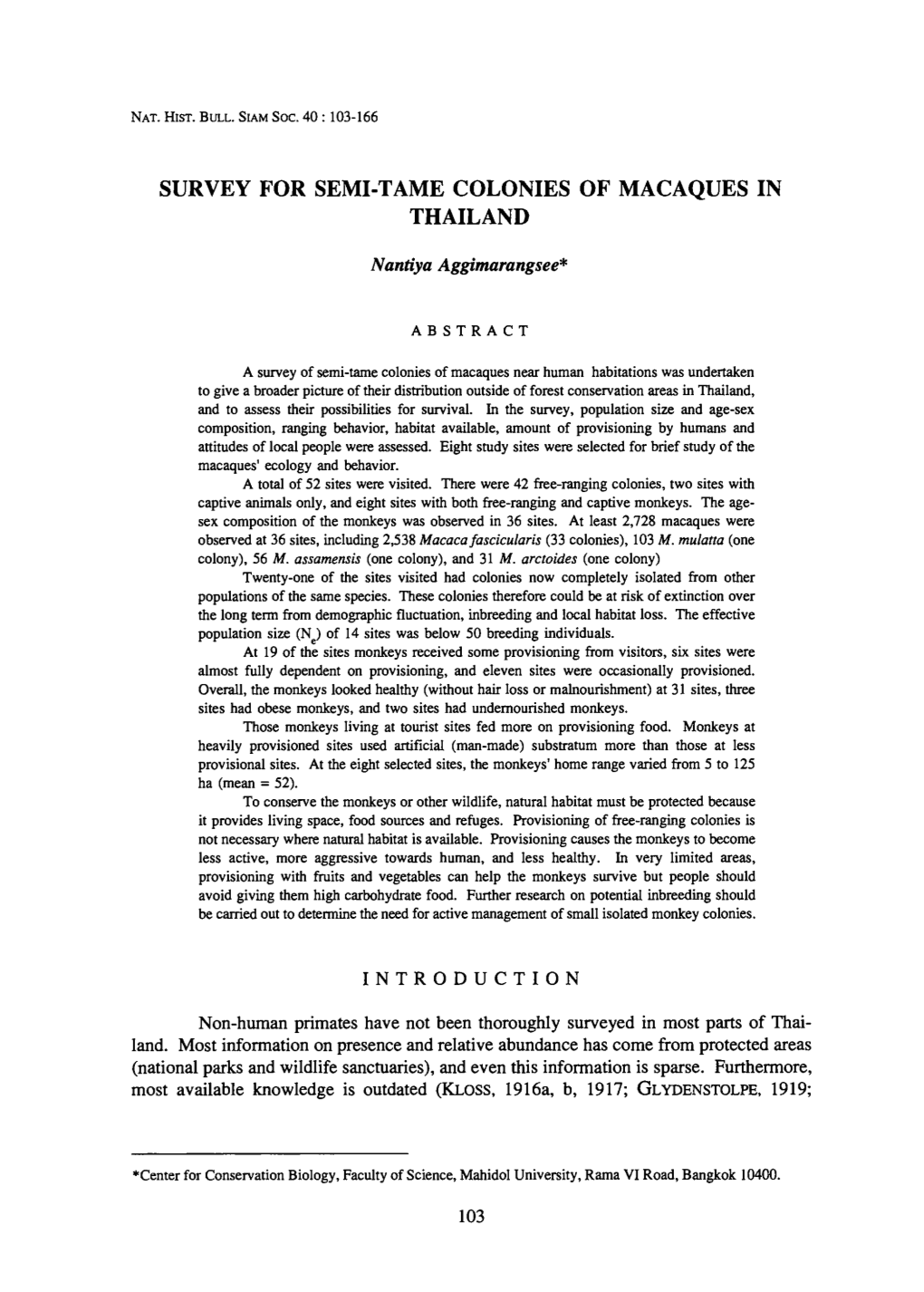

Survey for Semi-Tame Colonies of Macaques in Thailand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paper Title: Rocket Festival in Transition: Rethinking 'Bun Bangfai

1 Paper Title: Rocket Festival in Transition: Rethinking ‘Bun Bangfai’ in Isan Name of Author: Pinwadee Srisupun Ph.D. Candidate in Sociology, Khon Kaen University, Thailand Advisor: Dr. Yaowaluk Apichartwallob Assoc.Prof., Khon Kaen University, Thailand Address & Contact details: Faculty of Liberal Arts, Ubon Ratchathani University, Ubon Ratchathani 34190 Thailand Tel: + 66 45 353 725 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Panel prefer to presentation: Socio – Cultural Transformation Abstract Every year from May to June, ethnic Lao from Laos and Northeastern Thailand hold a rocket festival called Bun Bangfai. Traditionally, rockets were launched in the festival to ask the gods, Phaya Thaen and the Naga, to produce rain in the human world for rice farming and as a blessing for happiness. The ritual combines fertility rites which are important to the agrarian society with the Buddhist concept of making merit. There is no precise history of the festival, but some believe that it originated in Tai or Dai culture in China’s Yunnan Province. The province of Yasothon in Thailand is very popular for tourists who seek traditional culture. We can see the changing of Bun Bangfai from the past to present which includes pattern, ideas, and level of arrangement and from the original ritual to some unrelated ones. This paper presents a preliminary study about Bun Bung Fai in Isan focusing on Yasothon Province of Thailand case, not only because it is well known, but it is also an international festival clearly showing the process of commodification. How can we deal with Bun Bangfai festival of Yasothon especially the commodification process from local to global level? And from this festival, how can we interpret and understand Isan people’s way of life? The study found that the festival was full of capitalists, local and international who engage in every site. -

Infected Areas As on 26 January 1989 — Zones Infectées an 26 Janvier 1989 for Criteria Used in Compiling This List, See No

Wkty Epidem Rec No 4 - 27 January 1989 - 26 - Relevé éptdém hebd . N°4 - 27 janvier 1989 (Continued from page 23) (Suite de la page 23) YELLOW FEVER FIÈVRE JAUNE T r in id a d a n d T o b a g o (18 janvier 1989). — Further to the T r i n i t é - e t -T o b a g o (18 janvier 1989). — A la suite du rapport report of yellow fever virus isolation from mosquitos,* 1 the Min concernant l’isolement du virus de la fièvre jaune sur des moustiques,1 le istry of Health advises that there are no human cases and that the Ministère de la Santé fait connaître qu’il n’y a pas de cas humains et que risk to persons in urban areas is epidemiologically minimal at this le risque couru par des personnes habitant en zone urbaine est actuel time. lement minime. Vaccination Vaccination A valid certificate of yellow fever vaccination is N O T required Il n’est PAS exigé de certificat de vaccination anuamarile pour l’en for entry into Trinidad and Tobago except for persons arriving trée à la Trinité-et-Tobago, sauf lorsque le voyageur vient d’une zone from infected areas. (This is a standing position which has infectée. (C’est là une politique permanente qui n ’a pas varié depuis remained unchanged over the last S years.) Sans.) On the other hand, vaccination against yellow fever is recom D’autre part, la vaccination antiamarile est recommandée aux per mended for those persons coming to Trinidad and Tobago who sonnes qui, arrivant à la Trinité-et-Tobago, risquent de se rendre dans may enter forested areas during their stay ; who may be required des zones de -

Thailand Singapore

National State of Oceans and Coasts 2018: Blue Economy Growth THAILAND SINGAPORE National State of Oceans and Coasts 2018: Blue Economy Growth THAILAND National State of Oceans and Coasts 2018: Blue Economy Growth of Thailand July 2019 This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes or to provide wider dissemination for public response, provided prior written permission is obtained from the PEMSEA Executive Director, acknowledgment of the source is made and no commercial usage or sale of the material occurs. PEMSEA would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale, any commercial purpose or any purpose other than those given above without a written agreement between PEMSEA and the requesting party. Published by Partnerships in Environmental Management for the Seas of East Asia (PEMSEA). Printed in Quezon City, Philippines PEMSEA and Department of Marine and Coastal Resources (DMCR, Thailand). 2019. National State of Oceans and Coasts 2018: Blue Economy Growth of Thailand. Partnerships in Environmental Management for the Seas of East Asia (PEMSEA), Quezon City, Philippines. 270 p. ISBN 978-971-812-056-9 The activities described in this report were made possible with the generous support from our sponsoring organizations - the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of PEMSEA Country Partners and its other participating organizations. The designation employed and the presentation do not imply expression of opinion, whatsoever on the part of PEMSEA concerning the legal status of any country or territory, or its authority or concerning the delimitation of its boundaries. -

Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 120/2013

Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 120/2013. (See end of Document for details) Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 120/2013 of 11 February 2013 entering a name in the register of protected designations of origin and protected geographical indications ( (Khao Hom Mali Thung Kula Rong-Hai) (PGI)) COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) No 120/2013 of 11 February 2013 entering a name in the register of protected designations of origin and protected geographical indications ( (Khao Hom Mali Thung Kula Rong-Hai) (PGI)) THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION, Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Having regard to Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 November 2012 on quality schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs(1), and in particular Article 52(3)(b) thereof, Whereas: (1) Pursuant to Article 6(2) of Council Regulation (EC) No 510/2006 of 20 March 2006 on the protection of geographical indications and designations of origin for agricultural products and foodstuffs(2), an application from Thailand received on 20 November 2008 to register the name ‘ (Khao Hom Mali Thung Kula Rong-Hai)’ as a protected geographical indication was published in the Official Journal of the European Union(3). (2) Belgium, France, Italy, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom lodged objections to such registration under Article 7(1) of Regulation (EC) No 510/2006. The objections were deemed admissible under points (a), (b), (c) and (d) the first subparagraph of Article 7(3) thereof. -

Innovation for Public Service in Managing in Intrusion of Public Areas”

“Innovation for Public Service in Managing in Intrusion of Public Areas” Roi Et Municipality, Mueang Roi Et District, Roi Et Province --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Innovation for Public Service in Managing in Intrusion of Public Areas Roi Et Municipality, Mueang Roi Et District, Roi Et Province THAILAND Table of Content 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 2. Problems ................................................................................................................ 2 3. Challenges ............................................................................................................. 5 4. Guidelines for problem resolution .................................................................. 5 5. Innovation .............................................................................................................. 6 6. Purpose .................................................................................................................. 8 7. Method of operation ........................................................................................... 9 8. Success indicators .............................................................................................. 17 9. Obstacles in operations and solutions to the problem. .......................... 17 10. Benefits ............................................................................................................ -

Isan New Testament

“The Isan Saga” (An Abbreviated Version) “Faith Comes By Hearing; That is, Hearing the Word of God” Thailand and the Isan Region One-Third of Total Population & Landmass 40/12 Million In 1973 68/25 Million+ In 2016 Without Any Scriptures In Their Heart Language!! Isan New Testament Completed, Printed, Distributed “Faith Comes By Hearing; That is, Hearing the Word of God” Romans 10:17 Target Audience: Christian Minority Rural, Agrarian Isan Peasant Worker-class High Literacy Rate; Low Education & Opportunity Level; Thai Bible Hard to Understand ; Nearly 100% Buddhist. After 20-plus Years of Work Here’s The First Scriptures Ever In The Heart Language Of 25-Million Isan People Attractive Three-Cross Cover Design Isan being An Unwritten Language, The Thai Script and Spelling Rules Were Adapted John 3:16 เพราะว่าพระเจ้าทรงรักโลกยิ่งนัก จนได้ทรงประทานพระบุตรองค์เดียว ของพระองค์ที่บังเกิดมา เพื่อผู้ใดที่เชื่อในพระบุตรนั้นจะไม่พินาศ แต่มีชีวิตนิรันดร์ Christian-owned Four-One Printers Left-to-Right: Ron Myers, Ms. Kai (Owner), Dr. Steve Combs, Ms. Kai’s Assistant Isan New Testaments In Process Christian Print Shop Owner, Ms. Kai, Gave A Special Price Per Copy (62 Baht Each, or $1.70) Isan New Testament Covers All Bible Materials Imported From Finland, Same as Thai Gideon New Testaments Ron Reads First Completed Isan NT Location: Alliance Guest Home, Bangkok Thailand Ron Gives Isan NT To Isan Taxi Driver Isan New Testament Foreword Contains “Consideration Creation” Evangelism Booklet Dedication & Presentation Venue Second Floor, Rhombus Industries -

The Analysis of Problem and Threat of Small and Medium Enterprises In

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Clute Institute: Journals International Business & Economics Research Journal – September 2010 Volume 9, Number 9 The Analysis Of Problem And Threat Of Small And Medium-Sized Enterprizes In Northeast Thailand Thongphon Promsaka Na Sakolnakorn, Prince of Songkla University, Thailand ABSTRACT The objectives of the study are: 1) to study the problems of small and medium-sized enterprises in the northeastern region of Thailand and 2) to analyze the problems of the operation and management of small and medium-sized enterprises in the northeastern region of Thailand. The researcher used a qualitative method with in-depth interviews of 30 entrepreneurs in small and medium-sized enterprises in northeast Thailand. In addition, content analysis was used to analyze this data. The researcher found five problems affecting SMEs in northeast Thailand: 1) public policy and government support, 2) financial support, 3) knowledge capital, 4) labor, and 5) marketing. Keywords: Small and Medium-sized Enterprises, Problem and Threat, Northeast of Thailand INTRODUCTION ne of the potential processes to develop the economy in the country is to spread modernity to all regions of the country. When modernization comes to the area economic growth will follow, especially for small and O medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which are very important in developing countries. SMEs are crucial to a developing country because they increase the growth of the economy and industry in the country (Chen & Rozelle, 1999). SMEs still are one of the important factors that help and support the growth of the economy over the decades. -

Alternative Agriculture in Isan: a Way out for Small-Scale Farmers Michael J

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Master's Capstone Projects Center for International Education 1997 Alternative Agriculture in Isan: A Way Out for Small-Scale Farmers Michael J. Goldberg Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cie_capstones Part of the Education Commons Goldberg, Michael J., "Alternative Agriculture in Isan: A Way Out for Small-Scale Farmers" (1997). Master's Capstone Projects. 150. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cie_capstones/150 This Open Access Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for International Education at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALTERNATIVE AGRICULTURE IN ISAN: A WAY OUT FOR SMALL-SCALE FARMERS A Thesis Presented by MICHAEL J. GOLDBERG Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF EDUCATION May 1997 School of Education TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS I. INTRODUCTION 1 11. THAI DEVELOPMENT: THEORETICAL AND 3 EXPLANATORY CONSIDERATIONS A. Thai Society: A Marxist Perspective 4 B. Human Ecology 6 C. Political Economy 8 Ill. THAI HISTORICAL PROCESS: SOCIAL, ECONOMIC 9 AND POLITICAL CHANGE IN RURAL THAILAND A. Changing Landscape: The Opening of Thailand to 10 the World Market B. Welcome into the Fold: Isan is Incorporated into 13 the Thai State C. Cash Cropping in Isan: 1950's Onward 14 D. Contesting Alternatives 16 IV. TIME FOR CHANGE: A CONVERGENCE OF FACTORS 19 SUPPORT ALTERNATIVE AGRICULTURE A. -

The Diversity of Acorn Barnacles (Cirripedia, Balanomorpha) Across Thailand’S Coasts: the Andaman Sea and the Gulf of Thailand

Zoosyst. Evol. 93 (1) 2017, 13–34 | DOI 10.3897/zse.93.10769 museum für naturkunde The diversity of acorn barnacles (Cirripedia, Balanomorpha) across Thailand’s coasts: The Andaman Sea and the Gulf of Thailand Ashitapol Pochai1, Sutin Kingtong1, Woranop Sukparangsi1, Salinee Khachonpisitsak1 1 Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Burapha University, Chon Buri, Thailand http://zoobank.org/9FF0B30A-A535-48DE-B756-BD1C0DFE2B92 Corresponding author: Salinee Khachonpisitsak ([email protected]) Abstract Received 11 October 2016 The acorn barnacle is a sessile crustacean, inhabiting the intertidal areas of tropical and Accepted 7 December 2016 temperate regions worldwide. According to current practices on Cirripedia morpholo- Published 11 January 2017 gy, shell, opercular valves, and arthropodal characters including cirri and mouthparts are used as a tool for taxonomic classification, and using these characteristics the pres- Academic editor: ent study aimed to provide better resolution for the barnacle diversity and geographical Michael Ohl distribution within coastlines of Thailand: the Andaman Sea and the Gulf of Thailand. A total of ten species belonging to three families (Chthamalidae, Tetraclitidae, and Bal- Key Words anidae) were identified in this study. Subsequently, five species were newly recorded for the first time from Thailand’s coasts: Newmanella spinosus Chan & Cheang, 2016, Eu- acorn barnacle raphia hembeli Conrad, 1837, Euraphia depressa (Poli, 1795), Tetraclita kuroshioensis Cirripedia Chan, Tsang & Chu, 2007, and Tetraclita singaporensis Chan, Tsang & Chu, 2007. The Balanomorpha others, already mentioned in previous records, include: Tetraclita squamosa (Bruguière, shell morphology 1789), Chthamalus malayensis Pilsbry, 1916, Amphibalanus amphitrite (Darwin, 1854), opercular valve Amphibalanus reticulatus (Utinomi, 1967), and Megabalanus tintinnabulum (Linnae- distribution us, 1758). -

When Does a Farmer Sell Rice?: a Case Study in a Village in Yasothon Province, Northeast Thailand

Southeast Asian Studies. Vol. 33, No.4, March 1996 When Does a Farmer Sell Rice?: A Case Study in a Village in Yasothon Province, Northeast Thailand Y oshiaki NAKADA * I Introduction Thailand is a big rice exporter, but the Northeast region, which accounts for more than one third of the country's total rice acreage, produces little surplus rice [Fukui 1993: 22, 52J . In the region, irrigated paddylands are limited and rice is mostly rainfed. Production fluctuates greatly from year to year, and this prevents farmers from producing a constant surplus [Kono 1991: 57, 63-65J. Recently, however, commercial cultivation of rice started in part of the region, including Yasothon Province [Kono and Nagata 1992: 242J. Na Hom village in Yasothon, which I studied in detail, sold about one half of the harvest in 1992, for example [Nakada 1995: 542, Fig. 8J. It is often reported that farmers in Thailand do not wait for a favorable price in future but sell rice immediately after the harvest [Horita 1991: 147J, and this appears to be true in general. One study reported that 77-86% of rice for sale was sold just after harvest in the Central Region and the North, while in the Northeast, only 8% was sold immediately and the rest later: 58% within one month and 34% two to five months after harvest [Zenkoku Nogyo Kyodo Kumiai Chuokai 1987: 45, Table 19J .1) Why farmers in the Northeast sell rice later is yet to be studied. This paper searches for reasons for the delayed transaction of rice based on a case study of Na Hom Village in Kham Khuan Kaeo District in Yasothon Province (Fig. -

Budgetworldclass Drives

Budget WorldClass Drives Chiang Mai-Sukhothai Loop a m a z i n g 1998 Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT) SELF DRIVE VACATIONS THAILAND 1999 NORTHERN THAILAND : CHIANG MAI - SUKHOTHAI AND BURMESE BORDERLANDS To Mae Hong Son To Fang To Chiang Rai To Wang Nua To Chiang Rai 1001 1096 1 107 KHUN YUAM 118 1317 1 SAN KAMPHAENG 1269 19 CHIANG MAI1006 MAE ON 1317 CHAE HOM HANG DONG SARAPHI 108 Doi Inthanon 106 SAN PA TONG 11 LAMPHUN 1009 108 116 MAE CHAEM 103 1156 PA SANG 1035 1031 1033 18 MAE THA Thung Kwian MAE LA NOI 11 Market 1088 CHOM TONG 1010 1 108 Thai Elephant HANG CHAT BAN HONG 1093 Conservation 4 2 1034 Centre 3 LAMPANG 11 To 106 1184 Nan 15 16 HOD Wat Phrathat 1037 LONG 17 MAE SARIANG 108 Lampang Luang KO KHA 14 MAE 11 PHRAE km.219 THA Ban Ton Phung 1103 THUNG 1 5 SUNGMEN HUA SOEM 1099 DOI TAO NGAM 1023 Ban 1194 SOP MOEI CHANG Wiang Kosai DEN CHAI Mae Sam Laep 105 1274 National Park WANG CHIN km.190 Mae Ngao 1125 National Park 1124 LI SOP PRAP OMKOI 1177 101 THOEN LAP LAE UTTARADIT Ban Tha 102 Song Yang Ban Mae Ramoeng MAE SI SATCHANALAI PHRIK 1294 Mae Ngao National Park 1305 6 Mae Salit Historical 101 km.114 11 1048 THUNG Park SAWAN 105 SALIAM 1113 7 KHALOK To THA SONG SAM NGAO 1113 Phitsa- YANG Bhumipol Dam Airport nuloke M Y A N M A R 1056 SI SAMRONG 1113 1195 Sukhothai 101 ( B U R M A ) 1175 9 Ban Tak Historical 1175 Ban 12 Phrathat Ton Kaew 1 Park BAN Kao SUKHOTHAI MAE RAMAT 12 DAN LAN 8 10 105 Taksin 12 HOI Ban Mae Ban National Park Ban Huai KHIRIMAT Lamao 105 TAK 1140 Lahu Kalok 11 105 Phrathat Hin Kiu 13 104 1132 101 12 Hilltribe Lan Sang Miyawadi MAE SOT Development National Park Moei PHRAN KRATAI Bridge 1090 Centre 1 0 10 20 kms. -

24/7 Emergency Operation Center for Flood, Storm and Landslide

No. 13/2011, Tuesday, September 6, 2011, 11:00 AM 24/7 Emergency Operation Center for Flood, Storm and Landslide DATE: Tuesday, September 6, 2011 TIME: 09.00 LOCATION: Meeting Room 2, Ministry of Interior CHAIRPERSON: Mr. Panu Yamsri Director of Disaster Mitigation Directing Center, Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation 1. CURRENT SITUATION 1.1 Current flooded provinces: there are 10 recent flooded provinces: Sukhothai, Phichit, Phitsanulok, Nakhon Sawan, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya, Ang Thong, Chai Nat, Ubon Ratchathani, Sing Buri, and Chon Buri. The total of 50 Districts, 343 Sub-Districts, 2,038 Villages, 122,485 families and/or 393,808 people are affected by the flood. The total fatalities are 66 deaths and 1 missing. (Fatalities : 1 in Udon Thani, Sakon Nakhon, Uttaradit, Phetchabun; 2 in Tak, Nakhon Phanom, Roi Et, and Phang-Nga; 3 in Chiang Mai; 4 in Prachin Buri, Nakhon Sawan; 5 in Phitsanulok; 6 in Sukhothai; 7 in Mae Hong Son; 8 in Phrae; and 17 in Phichit: Missing : 1 in Mae Hong Son due to landslide) 1.2 Weather Condition: The monsoon trough lies across the North and the Northeast and the southwest monsoon over the Andaman Sea, Thailand and the Gulf of Thailand are intensifying. Increasing rainfall and isolated heavy fall is likely over upper the North and the Northeast and the East. People in the areas should beware of heavy rain during 1-2 days. (Thai Meteorological Department : TMD) 1.3 Amount of Rainfall: The heaviest rainfall in the past 24 hours is at Khaisi District of Bungkan Province at 163.0 mm.