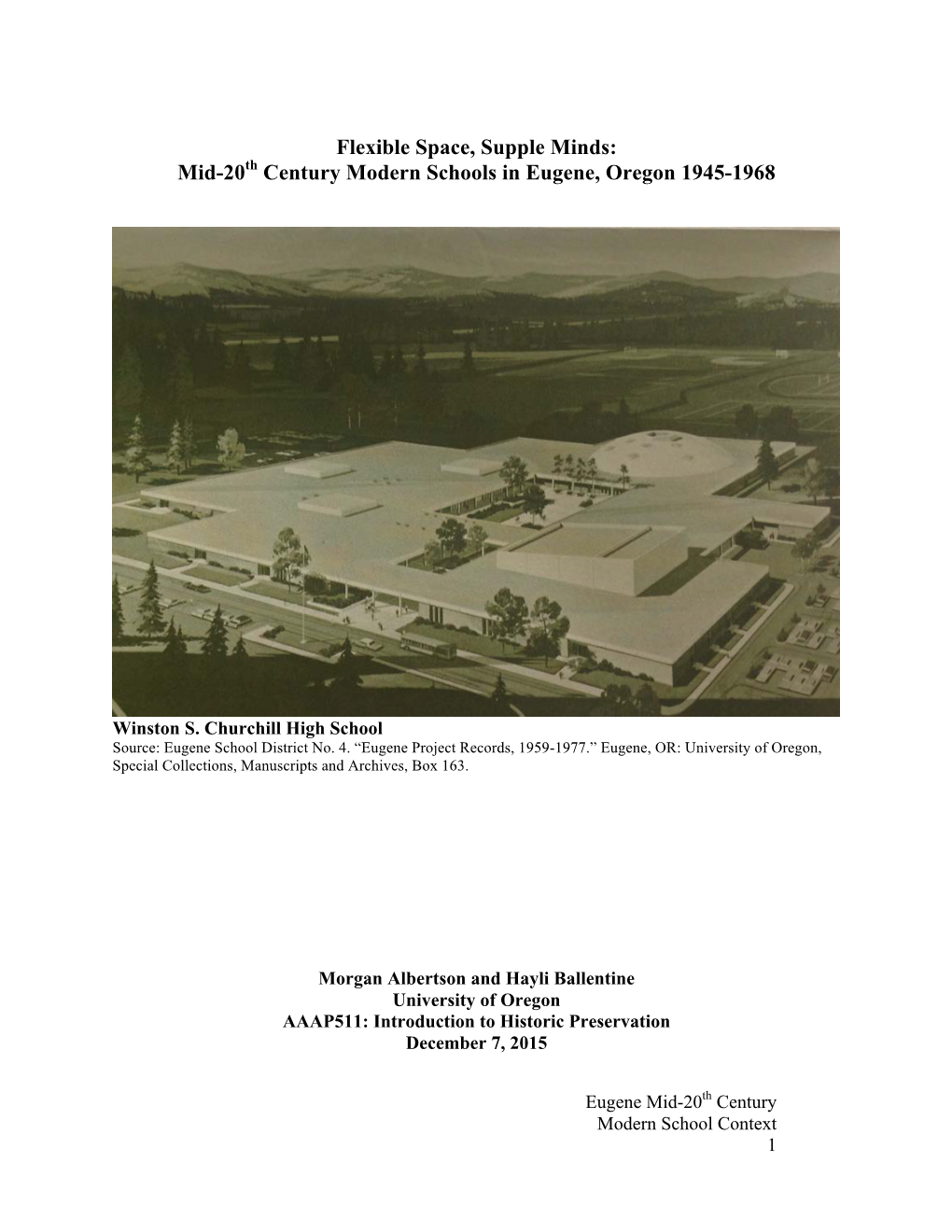

Mid-20Th Century Modern Schools in Eugene, Oregon 1945-1968

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-Gazette

VOL. 125 - NO. 15 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, APRIL 9, 2021 $.35 A COPY Public Meeting for the North End Residents Oppose Cross Street Hotel by Marie Simboli Silver Line Extension The North End community and its residents have mounted stiff opposition to a boutique luxury hotel planned for the property on the Alternatives Analysis Greenway-end of Salem Street. Since this project was fi rst proposed, residents have been saying that it is out of character with the neighborhood and many of their complaints are focused on its disruptive impact on the quality of life. Community stakeholders have organized a signature drive and have voiced opposition and it doesn’t appear that neighbors plan to go away, as they continue their message of “enough is enough” 134 key boutique hotel with 2 ground fl oors universal that North End residents DO NOT uses and seasonal roof top dining 300 people a WANT A HOTEL LOCATED THERE. 5-story building. Comments by business owner Dr. Paul M. 1. Blocking the view of greenway that has a Cangiano of Vision North: beautiful view with trees, grass and water sprin- “The North End needs every parking space it klers and residents enjoying that part of the park. can get its hands on. This proposed project is going to take public temporary/North End over- The MBTA and MassDOT project team will present an overview Residents will have no sunlight and no quality night parking spaces for its own benefi t. I have of the Silver Line Extension (SLX) Alternatives Analysis, share the of fresh air patients that use these spots daily to run into my fi ndings so far, and gather input from the community at a virtual 2. -

North Eugene High School

Spotlight on Success: North Eugene High School “We’re experiencing more ownership of the school and more personalization. Hopefully [we’re] changing the climate so that the kids realize this school belongs 1 to them and their parents and their community.” North Eugene High School (NEHS) is one of four comprehensive high schools in the Eugene (OR) School District 4J, with additional magnet and alternative schools available to Eugene students. There are just under 1000 students at NEHS. Laurie Henry is the campus principal and works with each of the three small school principals; she is finishing her second year at NEHS. Laurie has been an educator with the Eugene School District 4J for 33 years, first as an elementary teacher and learning specialist. She was later an administrator at the elementary, middle, and high school levels. A lot of Laurie Henry’s background involved work with at-risk and low income students. She sees herself as an instructional leader because she believes one of her strengths is around instruction. She said, “It’s really exciting to have teachers coming to learn how to differentiate learning rather than just teaching content and hoping the kids get it.” What’s working? Key Components to Success Small Learning Communities North Eugene High School is in their second year of housing three small schools within one larger school. E3:OSSI (Oregon Small Schools Initiative), funded by the Meyer Memorial Trust and the Gates Foundation, provided initial funding to convert the comprehensive high school to the small schools model. There are three small learning communities of approximately 70-100 students. -

North Eugene High School

North Eugene High School “Home of the Highlanders” Welcome to North Eugene High School! We are committed to providing our students with a rich, challenging, and meaningful educational experience. North Eugene High School offers a unique academic program that provides every student the opportunity to excel. Our caring staff is committed to helping every student fulfill their potential. We know that participation in activities outside of the classroom contributes to student engagement and academic achievement. Our goal is to promote academic achievement and engagement for all students at North. At North, we believe one of the best ways to learn is by doing. Our vision includes robust Career and Technical Education (CTE) Programs of Study, in which students can complete a pathway of courses, explore career interests, and exit NEHS prepared for high demand jobs. Our state-approved CTE programs include Digital Media, Early Childhood Education, Health Occupations, and more. In addition to all of these learning opportunities, we offer International Baccalaureate, Japanese and Spanish Immersion, Culinary Arts, and more. In short, there is something for everyone at North! This planning guide provides a menu of all the exciting courses designed to meet the varied interests and needs of our diverse community of learners. It is an essential tool in making the important educational decisions that lie ahead. We endeavor to offer a breadth of elective courses, while ensuring a variety of academic courses required for graduation. As you look through -

2018 Ford Scholars ‐ Sorted by State, City and Last Name (14 from Siskiyou County, California and 110 from Oregon)

2018 Ford Scholars ‐ Sorted by State, City and Last Name (14 from Siskiyou County, California and 110 from Oregon) Home College Planning on Attending # Home City Last Name First Name High School or Community College St 2018‐19 1 CA Etna Cruz‐Navarro Jorge Sonoma State University Etna High School 2 CA Etna Ireson‐Janke Anya University of California Los Angeles Yreka High School 3 CA Etna Morrill Caleb University of California Davis Etna High School 4 CA Fort Jones Watton Dakota Sonoma State University Etna High School 5 CA Happy Camp Barnett Brittany Southern Oregon University Happy Camp High School 6 CA Happy Camp Offield Madison University of California Los Angeles Happy Camp High School 7 CA Hornbrook Bortolussi Amiee California State University Chico Yreka High School 8 CA Mount Shasta Berg Clayton California State University Northridge Mt Shasta High School 9 CA Mount Shasta Carter Violet University of California Berkeley Weed High School 10 CA Tulelake Gonzalez‐Zuniga Gabriela California State University Chico Tulelake High School 11 CA Tulelake Weaver Cambria University of California Santa Cruz Tulelake High School 12 CA Weed Arnett Victoria Humboldt State University Weed High School 13 CA Yreka Mao Anni University of California Berkeley Yreka High School 14 CA Yreka Williams OliviaRose Humboldt State University Yreka High School 15 OR Ashland Diab Jack Southern Oregon University Ashland High School 16 OR Ashland Gottschalk Aspyn Oregon State University Ashland High School 17 OR Ashland Safay Gabriela Oregon State University Logos -

0131-PT-A Section.Indd

Team founder YOUR ONLINE LOCAL Harry Glickman New world view TRAIL BLAZER refl ects on his DAILY NEWS Portland International Film NBA career Festival adds a little love www.portlandtribune.com PortlandSee SPORTS, B8 Tribune— See LIFE, B1 THURSDAY, JANUARY 31, 2013 • TWICE CHOSEN THE NATION’S BEST NONDAILY PAPER • PUBLISHED THURSDAY Cluster ■ Developments on Columbia River levee now deemed safety concerns plan ties parents in knots Many worry changes would water down Chief Joseph success By JENNIFER ANDERSON The Tribune The story time rug in Er- in Quinton’s classroom isn’t big enough to hold all of her students. Some of her 31 second-grad- ers spill onto the bare fl oor or sit in desk chairs behind the group. That’s about six or seven more than what Quinton — a teacher of six years at North Portland’s Chief Joseph Elemen- tary School — considers ideal. “So much is behavior man- agement,” says Quinton, whose teaching career began in Cali- otorists, bicyclists and jog- towers and miles of utility lines. fornia about 30 years ago. With gers enjoying Columbia “Everything’s changed since Ka- 31 students, River views along Marine trina,” says Dave Hendricks, director “we don’t have MDrive may not realize it, of special projects for Multnomah the materials; Levee holds but they’re traveling atop a mound of County Drainage District No. 1. “We want we don’t have sand that’s the main bulwark against “All this stuff is no longer accept- to be part the time. ... I massive fl ooding of North and North- able,” he says, unless engineers can of the don’t dive into east Portland. -

Lane County Voters Pamphlet

LANE COUNTY VOTERS’ LANE COUNTY VOTERS’ LANEPAM COUNTYPHLET PAMPH LET VOTERS’MAY 19, 2015 SPECIALPAMPHLET ELECTION MAY 19, 2015 SPECIAL ELECTION MAY 21, 2019 SPECIAL ELECTION The publication and distribution of this pamphlet is provided by Thethe publicationCounty Clerk and at distributionthe direction of ofthis the pamphlet County Commissioners.is provided by theThe County candidate Clerk and at themeasure direction information of the County was provided Commissioners. by Thecandidates, candidate special and measure districts, information and other interested was provided parties by that candidates,chose to participate special districts, in this portion and other of the interested election partiesprocess. that chose to participate in this portion of the election process. Your ballot will contain only those measures and candidates Yourwhich ballot you willare containeligible onlyto vote those on, measuresbased on whereand candidates you live. which you are eligible to vote on, based on where you live. Table of Contents Community College Candidate Statements: Lane Community College .........................................................................................................................20-3 Education Service District Candidate Statements: Lane Education Service District ................................................................................................................20-5 School District Candidate Statements: Bethel School District #52.........................................................................................................................20-6 -

Duck Men's Basketball

ATHLETIC COMMUNICATIONS (MBB) Greg Walker [email protected] O: 541-346-2252 C: 541-954-8775 Len Casanova Center | 2727 Leo Harris Parkway | @OregonMBB | Facebook.com/OregonMBB | GoDucks.com 2020-21 SCHEDULE DUCK MEN’S BASKETBALL NOVEMBER RESULT SCORE No. 21 OREGON (1-1) vs. EASTERN WASHINGTON (0-2) 25 Eastern Washington PPD PPD Date Monday, December 7, 2020 DECEMBER TIME TV Tip Time 4:06 p.m. PT Site / Stadium / Capacity Eugene, Ore. / Matthew Knight Arena / 12,364 1 2 vs. Missouri L 75-83 Television Pac-12 Network 4 vs. Seton Hall 1 W 83-70 Ann Schatz, play-by-play; Elise Woodward, analyst Radio Oregon Sports Network (95.3 FM KUJZ in Eugene/Springfi eld) 7 Eastern Washington 4:00 PM Pac-12 Net Joey McMurry, play-by-play; Jerry Allen, analyst 9 Florida A&M 8:00 PM Pac-12 Net Live Stats GoDucks.com 12 at Washington * 5:00 PM Pac-12 Net Live Audio GoDucks.com Twitter @OregonMBB 23 UCLA * 12:00 PM ESPN2 Internet tunein.com 31 California * TBA TBA Satellite Radio Sirius ch. 135 / XM ch. 197 / Internet 957 JANUARY TIME TV SERIES HISTORY 2 Stanford * TBA TBA All-Time Oregon leads, 3-0 Last Meeting Oregon 81, Eastern Washington 47, Nov. 9, 2018 (Eugene, Ore.) 7 at Colorado * TBA TBA Current Streak Ducks +3 10 at Utah * TBA TBA Last UO Win Oregon 81, Eastern Washington 47, Nov. 9, 2018 (Eugene, Ore.) Last EWU Win NA 14 Arizona State * TBA TBA 16 Arizona * TBA TBA 23 Oregon State * TBA TBA THE STARTING 5 28 at UCLA * TBA TBA A pair of defending conference champions, No. -

Lane Community College Foundation 2015 ANNUAL REPORT

Lane Community College Foundation 2015 ANNUAL REPORT INVEST IN LANE. INVEST IN SUCCESS. For many of our students, Lane is their only safe space and our faculty, staff, students, and donors become their family. This “family” is real and critical to their success. MARY SPILDE, LANE COMMUNITY COLLEGE PRESIDENT A Letter from the President amily is an integral part of Lane Community College. Siblings, Fparents, children, cousins, and other relatives share the experience of a Lane education. I have met students who are the second, or even the third generation in their family to attend Lane, and others who are the first in their family to go to college. I know older adults inspired to complete their education because of their child’s experience here. When families embrace higher education together, the chances of success are much greater. For many of our students, Lane is their only safe space and our faculty, staff, students, and donors become their family. This “family” is real and critical to their success. Whether it’s a cohort of students in our Women’s Program, a staff member in the Veterans Center, a mentor in our Multicultural Center, an inspirational teacher, or a generous scholarship donor, students can find encouragement, assistance, and people who truly care about them. Just a few short months ago, our campus family came together to celebrate the grand opening of our renovated campus core. This transformative project included our library, tutoring center, quiet study space, and food services, as well as our well-known culinary student restaurant, the Renaissance Room. -

Minutes of the Regular Meeting of Board of Directors School District No

MINUTES OF THE REGULAR MEETING OF BOARD OF DIRECTORS SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 4J, LANE COUNTY, OREGON December 7, 2005 Meeting Convened The Board of Directors of School District No. 4J, Lane County, Eugene, Oregon, held a regular meeting on December 7, 2005, at 7 p.m., at the Education Center, 200 North Monroe Street, Eugene, Oregon. Notice of the meeting was mailed to the media and posted in Education Center on December 2, 2005, and published in The Register-Guard on December 5, 2005. ROLL CALL BOARD MEMBERS: Beth Gerot, Chair Tom Herrmann, Vice-Chair Eric Forrest Charles Martinez, Jr. Craig Smith Virginia Thompson STAFF: Barbara Bellamy, Director, Communications and Intergovernmental Relations Ted Heid, Director of Labor Relations Tom Henry, Deputy Superintendent and Chief Academic Officer Hillary Kittleson, Director of Financial Services Susan Fahey, Operations and Reporting Manager Caroline Passerotti, Financial Analyst STUDENT REPRESENTATIVES: Katie Parker, Churchill High School Jordan Ries, North Eugene High School MEDIA: Anne Williams, The Register-Guard KEZI News CALL TO ORDER, ROLL CALL, AND FLAG SALUTE Board Chair Beth Gerot called the meeting to order at 7 p.m. and led the salute to the flag. She noted that Board Member Anette Spickard and Superintendent George Russell would not be present at the meeting. Deputy Superintendent Tom Henry would be filling in for Superintendent Russell. INTRODUCTION OF GUESTS AND SUPERINTENDENT’S REPORT Mr. Henry introduced the following guests who would be speaking to the first item of information of the agenda: Mike Garling, temporary principal at Edgewood/Evergreen School, Marily Walker, a teacher at Evergreen, Julie Hulme, a teacher at Edgewood, Laura Blake Jones, a parent at Evergreen, and Kris Shaughnessy, a parent at Edgewood. -

Theodore Roosevelt Junior High School Eugene, Oregon 1949–2016

THEODORE ROOSEVELT JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL EUGENE, OREGON 1949–2016 Liz Carter HERITAGE RESEARCH ASSOCIATES REPORT NO. 412 THEODORE ROOSEVELT JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL, EUGENE, OREGON, 1949–2016 by Liz Carter Prepared for Eugene School District 4J Eugene, Oregon Heritage Research Associates, Inc., 1997 Garden Avenue Eugene, Oregon 97405 March 2016 Heritage Research Associates Report No. 412 ABSTRACT The 1949–1950 International Style Roosevelt Junior High (Middle) School, in Eugene, Lane County, Oregon, was designed by Portland architects Wolff and Phillips. Built to its current configuration over a period of years, it replaced the 1924 Roosevelt Junior High, which was converted to Condon Elementary School in 1953 and is now owned by the University of Oregon, known as Agate Hall. The subject school is representative of the community’s response to post-World War II population growth as well as the changing architectural trends of the mid-twentieth century. As evaluated under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act, Roosevelt Middle School was found to be historically significant for its association with post-World War II educational shifts and trends, and for its architectural character as a good local example of the International Style, which came into common use in the years following the war. Although not the first post-war school constructed in Eugene—it was preceded by Colin Kelly Junior High—and certainly not the last to be built in response to the Baby Boom, Roosevelt became a lauded focal point of new, progressive pedagogical approaches, and the building reflected those ideas architecturally. The original portion of the new school building was constructed in 1949–1950, with historic-period additions made between 1950 and 1957 (in 1950, 1951, 1954, 1955, and 1957). -

Highlander Parents and Students

North Eugene High School Academic Planning Guide 2017-18 NEHS Academic Planning Guide Page 1 Table of Contents Graduation Requirements………………………………..………………………………………..…………… 3 College Credit at North Eugene…………………………….………………………………….……………… 6 RTEC………………………………………………….………………………………………..…...…………… 8 Career Skills………………………………………………………….…………………………………..……… 9 Academic Recognition…………….…………………………………….……………………………………… 10 Applied & Fine Arts………………………………….………………………..………………………………… 11 Art / Graphic / Digital……………………………………………………..……………………………… 12 Drama …..……………………………………………………………………...………………………… 14 Music………………………………………………………..………………………………………….. 15 Industrial Education………………………………………….………………………………………… 17 Family & Consumer Sciences………………………………………………………………………………… 18 Early Childhood Education……………………………………………………………………………… 18 Culinary ……..…………………………………………………………………………………………… 19 Health & PE ………..…………………………………………………………………………………………… 20 Language Arts…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 22 Mathematics…………………………..………………………………………………………………………… 24 Other Subjects………………………………..………………………………………………………………… 27 Computer Science………………………………………………………………………………………. 27 Science………………………………………………………..………………………………………………… 30 Social Studies………………………………………………………..………………………………………… 33 World Languages……………………………………………………….……………………………………… 35 American Sign Language ……………………………………………………………………………… 35 Japanese ………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 36 Spanish ………………………………………………………………………………………………… 36 Support Services……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 38 Special Education………………………………………………………………………………………. -

Transformational Leadership: Profile of a High School Principal. INSTITUTION Oregon School Study Council, Eugene

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 359 652 EA 025 093 AUTHOR Liontos, Lynn Balster TITLE Transformational Leadership: Profile of a High School Principal. INSTITUTION Oregon School Study Council, Eugene. REPORT NO ISSN-0095-6694 PUB DATE Jul 93 NOTE 65p. AVAILABLE FROMPublication Sales, Oregon School Study Council, University of Oregon, 1787 Agate Street, Eugene, OR 97403 ($7 prepaid, nonmember; $4.50 prepaid, member; $3 postage and handling on billed orders). PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) Historical Materials (060) JOURNAL CIT OSSC Bulletin; v36 n9 Jul 1993 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Administrator Characteristics; *Administrator Effectiveness; Biographies; Change Agents; Educational Improvement; High Schools; *Leadership Styles; Participative Decision Making; Personality Traits; *Principals; School Restructuring; *Teamwork IDENTIFIERS Caring; Empowerment; *Eugene Public Schools OR: Facilitator Styles; *Transformational Leadership ABSTRACT Drawing on extensive staff interviews, this publication profiles a high school principal in Eugene, Oregon, who exhibits many aspects of transformational leadership. Transformational leadership is improvement oriented and comprises three elements: (1) a collaborative, shared decision-making approach; (2) an emphasis on teacher professionalism and empowerment; and (3) an understanding of change, including how to encouragechange in others. Bob Anderson is principal at North Eugene High School, which has evolved into an outstanding, innovative school under his leadership. Chapter 1 tells how Anderson entered the administration field and describes his personality. Chapter 2, devoted to Anderson's first years at North Eugene, traces his evolution as a transformational leader and describes how he set the stage for risk-taking, growth, and change. Chapters 3 through 7 focus on five key aspects of transformational leadership: working in teams, seeing the big picture, empowering others, creating ownership, and continually improving the school.