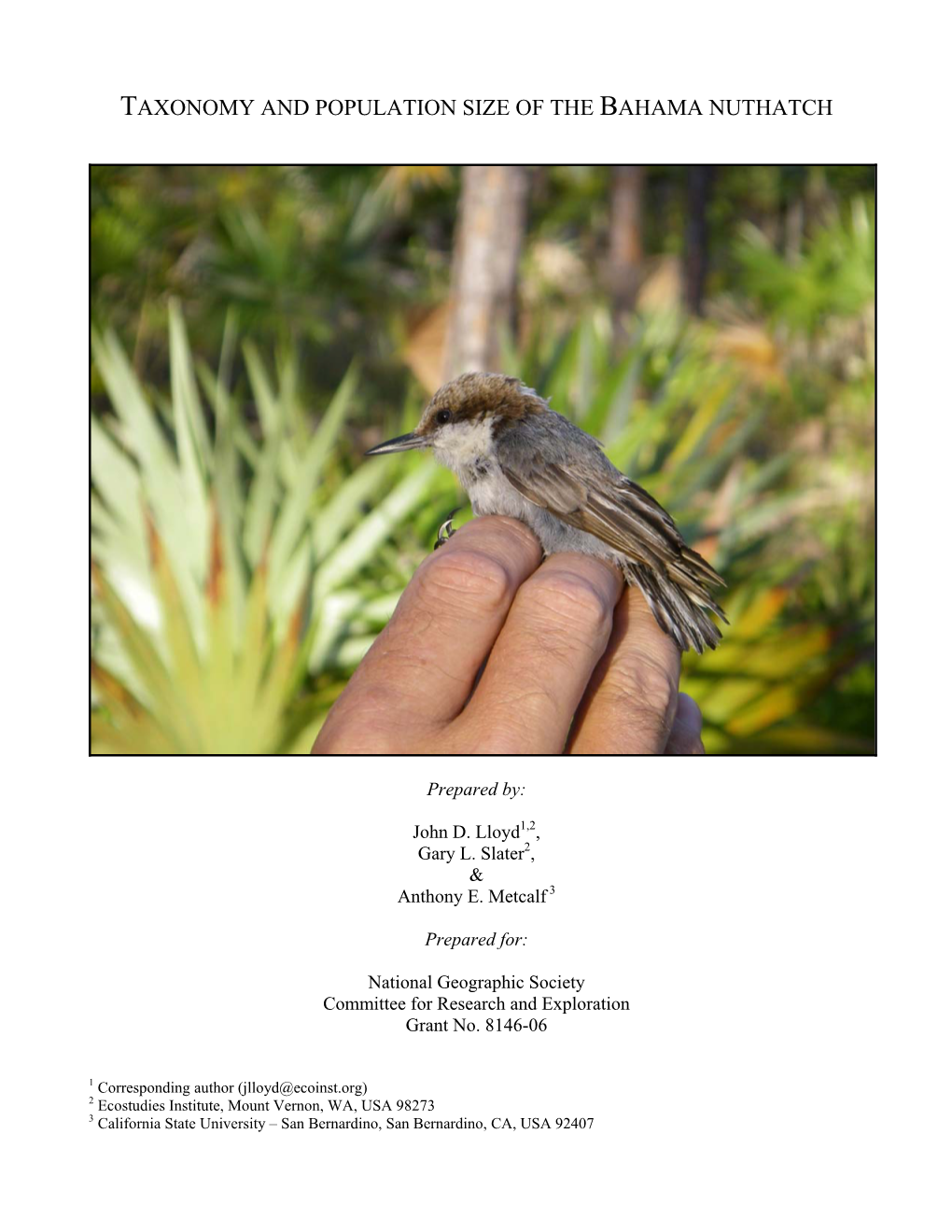

Taxonomy and Population Size of the Bahama Nuthatch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Checklist of Florida'a Birds

Artwork by Ann Marie Tavares 2016 Checklist of Florida’s Birds Prepared by Dr. Greg Schrott and Andy Wraithmell The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Florida’s wild places are home to an incredible diversity of birds. Over 500 native bird species or naturally occurring strays have been recorded in the state in historic times, and about 330 native species commonly occur here (four have gone extinct). A further 14 nonnative species are considered to have established large, stable populations in Florida. More than 70 natural community types support this diversity, from the pine flatwoods of Apalachicola National Forest, to the scrub communities of the Lake Wales Ridge, and the vast sawgrass marshes and mangrove swamps of Everglades National Park. Our natural areas harbor many bird species seen nowhere else in the United States such as the Florida Scrub-Jay, Mangrove Cuckoo, and Snail Kite. In addition, Florida’s birdlife changes with the cycle of the seasons. A constant turnover of breeding, wintering and migratory species provides new birding experiences throughout the year. To help you keep track of the spectacular range of birdlife the state has to offer, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) has published this checklist. The first edition of Checklist of Florida’s Birds was prepared by Dr. Henry M. Stevenson in 1986. During his lifetime, Dr. Stevenson made many contributions to the field of ornithology, culminating with his writing The Birdlife of Florida with Bruce H. Anderson (1994). This book offers the most comprehensive information published on the lives of Florida’s birds. -

Florida State University Libraries

)ORULGD6WDWH8QLYHUVLW\/LEUDULHV 2018 Using a Call-Response Occupancy Survey with Brown-headed Nuthatches (Sitta pusilla) to Evaluate the Biological Species Concept Heather Levy Follow this and additional works at DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS & SCIENCES USING A CALL-REPONSE OCCUPANCY SURVEY WITH BROWN-HEADED NUTHATCHES (SITTA PUSILLA) TO EVALUATE THE BIOLOGICAL SPECIES CONCEPT By HEATHER LEVY A Thesis submitted to the Department of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with Honors in the Major Degree Awarded: Spring 2018 ! Heather Levy FSU EAOS Honors Thesis Using a Call-Response Occupancy Survey with Brown-headed Nuthatches (Sitta pusilla) to Evaluate the Biological Species Concept Abstract The status of the endangered Bahama Nuthatch (Sitta insularis) as an independent species is being debated. The Bahama Nuthatch currently is listed as a subspecies of the Brown-headed Nuthatch (Sitta pusilla), even though the two differ in morphology, song, genetic characteristics, and range. According to the biological species concept, if two populations of the same species are unable to vocally recognize one another, then the two populations would not be able to interbreed, inferring two distinct species. Birds generally react more aggressively to vocalizations of conspecifics, or of the same species, than those of non-predatory heterospecifics, or of a different species, because two members of one species are in closer competition for mates, resources, and territories. In this study, I used a call-response occupancy survey at St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge to determine if using playback increased detection probabilities of Brown-headed Nuthatches. -

Cuba Birding Tour – March 2017

CUBA BIRDING TOUR – MARCH 2017 By Chris Lotz Cuban Tody, photographed on this tour by Jean Kirkwood www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | T R I P R E P O R T Cuba Birding Tour: March 2017 This was another fantastic Cuban birding tour with a wonderful group of participants. We found all the Cuban and regional endemics we were targeting, except for Gundlach’s Hawk, and we also saw a truly excellent number of North American migrants, such as a plethora of colorful wood warblers. The smallest bird in the world, Bee Hummingbird, numerous Cuban Trogon and Cuban Tody sightings, and brilliant views of Blue-headed Quail-Dove, Grey-fronted Quail-Dove and Key West Quail-Dove were some of the many avian highlights. A map showing the route we take on our annual set departure Cuba trip – we do Jamaica as an extension and in future years we’ll be adding other Caribbean destinations such as the Dominican Republic Day 1, 1 March 2017. Arrival in Havana All nine of us arrived early before the tour was to officially begin tomorrow. From our comfortable base near Havana airport we already started getting nicely acquainted with some of the single-island and regional endemics. There was a Cuban Emerald nest right outside the back door of the place we stayed (http://www.donaamaliacuba.com/en/place) and Red- legged Thrush was very much in evidence (as it always is throughout Cuba, even in the middle of cities). Antillean Palm Swift winged its way overhead, and Cuban Pewee showed very well and gave its characteristic call. -

Blue-Gray Gnatcatcher

Blue-gray Gnatcatcher Polioptila caerulea Taxa: Avian SE-GAP Spp Code: bBGGN Order: Passeriformes ITIS Species Code: 179853 Family: Sylviidae NatureServe Element Code: ABPBJ08010 KNOWN RANGE: PREDICTED HABITAT: P:\Proj1\SEGap P:\Proj1\SEGap Range Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Range_bBGGN.pdf Predicted Habitat Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Dist_bBGGN.pdf GAP Online Tool Link: http://www.gapserve.ncsu.edu/segap/segap/index2.php?species=bBGGN Data Download: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/region/vert/bBGGN_se00.zip PROTECTION STATUS: Reported on March 14, 2011 Federal Status: --- State Status: ID (P), KY (N), NJ (INC/S), NV (YES), NY (PB), RI (Not Listed), UT (None), UT (None), BC (8 (2005)), QC (Non suivie) NS Global Rank: G5 NS State Rank: AL (S5B,S3N), AR (S5B), AZ (S5), CA (S4), CO (S5B), CO (S5B), CT (S5B), CT (S5B), DC (S3B,S3N), DE (S5B), FL (SNRB,SNRN), GA (S5), IA (S4B,S4N), ID (S3?), IL (S5), IN (S4B), KS (S4B), KY (S5B), LA (S3N,S4B), MA (S4B), MD (S5B), ME (S2S3), MI (S5), MN (SNRB), MO (SNRB), MS (S5B), MS (S5B), MT (S1B), NC (S5B,S2N), NE (S4), NH (S4B), NJ (S4B), NM (S4B,S4N), NV (S4B), NY (S5), OH (S5), OK (S5B), OR (S3B), PA (S5B), RI (S4B), SC (SNRB,SNRN), SD (S1B), SD (S1B), TN (S5), TX (S3B), UT (S5B), UT (S5B), VA (S5), VT (S3B), VT (S3B), WA (SNA), WI (S4B), WI (S4B), WV (S5B), WY (S3?B), WY (S3?B), AB (SNA), BC (SNA), LB (SNA), MB (SNA), NB (SNA), NF (SNA), NS (SNA), ON (S4B), PE (SNA), QC (S4B), SK (SNA) bBGGN Page 1 of 6 SUMMARY OF PREDICTED HABITAT BY MANAGMENT AND GAP PROTECTION STATUS: US FWS US Forest Service Tenn. -

Bird Checklist Guánica Biosphere Reserve Puerto Rico

United States Department of Agriculture BirD CheCklist Guánica Biosphere reserve Puerto rico Wayne J. Arendt, John Faaborg, Miguel Canals, and Jerry Bauer Forest Service Research & Development Southern Research Station Research Note SRS-23 The Authors: Wayne J. Arendt, International Institute of Tropical Forestry, U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Sabana Field Research Station, HC 2 Box 6205, Luquillo, PR 00773, USA; John Faaborg, Division of Biological Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211-7400, USA; Miguel Canals, DRNA—Bosque de Guánica, P.O. Box 1185, Guánica, PR 00653-1185, USA; and Jerry Bauer, International Institute of Tropical Forestry, U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Río Piedras, PR 00926, USA. Cover Photos Large cover photograph by Jerry Bauer; small cover photographs by Mike Morel. Product Disclaimer The use of trade or firm names in this publication is for reader information and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture of any product or service. April 2015 Southern Research Station 200 W.T. Weaver Blvd. Asheville, NC 28804 www.srs.fs.usda.gov BirD CheCklist Guánica Biosphere reserve Puerto rico Wayne J. Arendt, John Faaborg, Miguel Canals, and Jerry Bauer ABSTRACt This research note compiles 43 years of research and monitoring data to produce the first comprehensive checklist of the dry forest avian community found within the Guánica Biosphere Reserve. We provide an overview of the reserve along with sighting locales, a list of 185 birds with their resident status and abundance, and a list of the available bird habitats. Photographs of habitats and some of the bird species are included. -

Common Birds of the Prescott Area Nuthatch.Cdr

Birds are listed by their typical habitats. Coniferous Forest Riparian (Creekside) Woodland (Some species may be found in more Sharp-shinned Hawk (w) Anna's Hummingbird (s) than one habitat.) Cooper's Hawk Black-chinned Hummingbird (s) (w) = winter (s) = summer Broad-tailed Hummingbird (s) Rufous Hummingbird (s) Acorn Woodpecker Black Phoebe Pinyon/Juniper/Oak Woodland Red-naped Sapsucker (w) Plumbeous Vireo (s) and Chaparral Hairy Woodpecker Warbling Vireo (s) Gambel's Quail . Western Wood-Pewee (s) House Wren (s) Ash-throated Flycatcher (s) Cordilleran Flycatcher (s) Lucy's Warbler (s) Western Scrub-Jay Hutton's Vireo Yellow Warbler (s) Bridled Titmouse Steller's Jay Summer Tanager (s) Juniper Titmouse . Mountain Chickadee Song Sparrow (w) Bushtit White-breasted Nuthatch Lincoln's Sparrow (w) Bewick's Wren . Pygmy Nuthatch Blue Grosbeak (s) Ruby-crowned Kinglet (w) Brown Creeper Brown-headed Cowbird (s) Blue-gray Gnatcatcher (s) Western Bluebird Bullock's Oriole (s) Crissal Thrasher Hermit Thrush Lesser Goldfinch Phainopepla (s) Yellow-rumped Warbler (w) Lake and Marsh Virginia's Warbler (s) Grace's Warbler (s) Black-throated Gray Warbler (s) Red-faced Warbler (s) Pied-billed Grebe Spotted Towhee Painted Redstart (s) Eared Grebe (w) Canyon Towhee Hepatic Tanager (s) Double-crested Cormorant Rufous-crowned Sparrow Western Tanager (s) Great Blue Heron White-crowned Sparrow (w) Chipping Sparrow Gadwall (w) Black-headed Grosbeak (s) Dark-eyed Junco (w) American Wigeon (w) Scott’s Oriole (s) Pine Siskin Mallard Lake and Marsh (cont.) Varied or Other Habitats Cinnamon Teal (s) Turkey Vulture (s) Common Birds Northern Shoveler (w) Red-tailed Hawk Northern Pintail (w) Rock Pigeon of the Green-winged Teal (w) Eurasian Collared-Dove Prescott Canvasback (w) Mourning Dove Ring-necked Duck (w) Greater Roadrunner Area Lesser Scaup (w) Ladder-backed Woodpecker Bufflehead (w) Northern Flicker Common Merganser (w) Cassin's Kingbird (s) Ruddy Duck (w) Common Raven American Coot Violet-green Swallow (s) . -

PPCO Twist System

A Brown-headed Nuthatch brings food to the nest. Color-coded leg bands enable the authors and their colleagues to discern the curious and potentially complex relationships among the various individuals at Tall Timbers Research Station on the Florida–Georgia line. Photo by © Tara Tanaka. photos by Tara Tanaka Tallahassee, Florida [email protected] 46 BIRDING • FEBRUARY 2016 arblers are gorgeous, jays boisterous, and sparrows elusive, Wbut words like “cute” and “adorable” come to mind when the conversation shifts to Brown-headed Nuthatches. The word “cute” doesn’t appear in the scientifc literature regularly, but science may help to explain its frequent association with nuthatch- es. The large heads and small bodies nuthatches possess have propor- tions similar to those found on young children. Psychologists have found that these proportions conjure up “innate attractive” respons- es among adult humans even when the proportions fall on strange objects (Little 2012). This range-restricted nuthatch associated with southeastern pine- woods has undergone steep declines in recent decades and is listed as a species of special concern in most states in which it breeds (Cox and Widener 2008). The population restricted to Grand Bahama Island appears to be critically endangered (Hayes et al. 2004). Add to these concerns some intriguing biology that includes helpers at the nest, communal winter roosts, seed caching, social grooming, and the use of tools, and you have some scintillating science all bound up in one “cute” and “adorable” package. James -

The Journal of Caribbean Ornithology

THE J OURNAL OF CARIBBEAN ORNITHOLOGY SOCIETY FOR THE C ONSERVATION AND S TUDY OF C ARIBBEAN B IRDS S OCIEDAD PARA LA C ONSERVACIÓN Y E STUDIO DE LAS A VES C ARIBEÑAS ASSOCIATION POUR LA C ONSERVATION ET L’ E TUDE DES O ISEAUX DE LA C ARAÏBE 2005 Vol. 18, No. 1 (ISSN 1527-7151) Formerly EL P ITIRRE CONTENTS RECUPERACIÓN DE A VES M IGRATORIAS N EÁRTICAS DEL O RDEN A NSERIFORMES EN C UBA . Pedro Blanco y Bárbara Sánchez ………………....................................................................................................................................................... 1 INVENTARIO DE LA A VIFAUNA DE T OPES DE C OLLANTES , S ANCTI S PÍRITUS , C UBA . Bárbara Sánchez ……..................... 7 NUEVO R EGISTRO Y C OMENTARIOS A DICIONALES S OBRE LA A VOCETA ( RECURVIROSTRA AMERICANA ) EN C UBA . Omar Labrada, Pedro Blanco, Elizabet S. Delgado, y Jarreton P. Rivero............................................................................... 13 AVES DE C AYO C ARENAS , C IÉNAGA DE B IRAMA , C UBA . Omar Labrada y Gabriel Cisneros ……………........................ 16 FORAGING B EHAVIOR OF T WO T YRANT F LYCATCHERS IN T RINIDAD : THE G REAT K ISKADEE ( PITANGUS SULPHURATUS ) AND T ROPICAL K INGBIRD ( TYRANNUS MELANCHOLICUS ). Nadira Mathura, Shawn O´Garro, Diane Thompson, Floyd E. Hayes, and Urmila S. Nandy........................................................................................................................................ 18 APPARENT N ESTING OF S OUTHERN L APWING ON A RUBA . Steven G. Mlodinow................................................................ -

Biological Resources Core Area

Sweetwater Reservoir/ San Miguel Mountains/ Sweetwater River BRCA 94 Jamul Mountains BRCA eArea.mxd Mountains/Marron Valley BRCA Project Area Proposed Proctor Valley Road Alignment Otay Lakes/Otay Mesa/ Otay Ranch RMP Preserve, Conserved Open Space and Non-Impacted LDA Otay River Valley BRCA Cores Linkages 0 1,700 3,400 Feet SOURCE: USGS 7.5-minute Topographic Map; Hunsaker 2017; SANGIS 2016 FIGURE 3-3 Biological Resources Core Area Otay Ranch Village 14 and Planning Areas 16/19 - Preserve Status Report NOTE: See Figure 6-2 for Corridor and Habitat Linkages Post Exchange and Boundary Line Adjustment Date: 2/8/2018 - Last saved by: mmcginnis - Path: Z:\Projects\j820701\MAPDOC\DOCUMENT\BTR\PreserveAppendix\Figure3_3_BioCor - Path: mmcginnis by: saved Last - 2/8/2018 Date: Otay Ranch Village 14 and Planning Areas 16/19 Otay Ranch RMP Preserve Status Report INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 8207 122 February 2018 L4 R1 L4 R1 94 L3 L3 R1 L4 PRESUMPTIVE CORRIDOR Project Area R1 Proposed Proctor Valley Road Alignment Otay Ranch RMP Preserve, Conserved Open Space and Non-Impacted LDA Otay Ranch Village 13 L3 Public Lands CDFW Owned Land L3 K R E Wildlife Crossings Z U A R1 L E Upper R7 U R D C Proctor Valley Land Use Otay Project Applicant Otay Ranch Development Reservoir R7 Project Applicant Otay Ranch Preserve feCorridors.mxd Existing Wildlife Corridors Major Local Corridor for Focal Mammal and Bird Species Regional Corridor for Focal Mammal and Bird Species R2 R10 Public Lands R2 BLM R2 CDFW R10 DOD USFWS R11 R2 R8 0 1,700 3,400 Lower Otay Reservoir -

The Evolution of Nest Construction in Swallows (Hirundinidae) Is Associated with the Decrease of Clutch Size

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Linzer biol. Beitr. 38/1 711-716 21.7.2006 The evolution of nest construction in swallows (Hirundinidae) is associated with the decrease of clutch size P. HENEBERG A b s t r a c t : Variability of the nest construction in swallows (Hirundinidae) is more diverse than in other families of oscine birds. I compared the nest-building behaviour with pooled data of clutch size and overall hatching success for 20 species of swallows. The clutch size was significantly higher in temperate cavity-adopting swallow species than in species using other nesting modes including species breeding in evolutionarily advanced mud nests (P<0.05) except of the burrow-excavating Bank Swallow. Decrease of the clutch size during the evolution of nest construction is not compensated by the increase of the overall hatching success. K e y w o r d s : Hirundinidae, nest construction, clutch size, evolution Birds use distinct methods to avoid nest-predation: active nest defence, nest camouflage and concealment or sheltered nesting. While large and powerful species prefer active nest-defence, swallows and martins usually prefer construction of sheltered nests (LLOYD 2004). The nests of swallows vary from natural cavities in trees and rocks, to self-exca- vated burrows to mud retorts and cups attached to vertical faces. Much attention has been devoted to the importance of controlling for phylogeny in com- parative tests (HARVEY & PAGEL 1991), including molecular phylogenetic studies of swallows (WINKLER & SHELDON 1993). Interactions between the nest-construction va- riability and the clutch size, however, had been ignored. -

Caribbean Naturalist No

Caribbean Naturalist No. 26 2015 Observations of New Bird Species for San Salvador Island, The Bahamas Michael E. Akresh and David I. King The Caribbean Naturalist . ♦ A peer-reviewed and edited interdisciplinary natural history science journal with a re- gional focus on the Caribbean ( ISSN 2326-7119 [online]). ♦ Featuring research articles, notes, and research summaries on terrestrial, fresh-water, and marine organisms, and their habitats. The journal's versatility also extends to pub- lishing symposium proceedings or other collections of related papers as special issues. ♦ Focusing on field ecology, biology, behavior, biogeography, taxonomy, evolution, anatomy, physiology, geology, and related fields. Manuscripts on genetics, molecular biology, anthropology, etc., are welcome, especially if they provide natural history in- sights that are of interest to field scientists. ♦ Offers authors the option of publishing large maps, data tables, audio and video clips, and even powerpoint presentations as online supplemental files. ♦ Proposals for Special Issues are welcome. ♦ Arrangements for indexing through a wide range of services, including Web of Knowledge (includes Web of Science, Current Contents Connect, Biological Ab- stracts, BIOSIS Citation Index, BIOSIS Previews, CAB Abstracts), PROQUEST, SCOPUS, BIOBASE, EMBiology, Current Awareness in Biological Sciences (CABS), EBSCOHost, VINITI (All-Russian Institute of Scientific and Technical Information), FFAB (Fish, Fisheries, and Aquatic Biodiversity Worldwide), WOW (Waters and Oceans Worldwide), and Zoological Record, are being pursued. ♦ The journal staff is pleased to discuss ideas for manuscripts and to assist during all stages of manuscript preparation. The journal has a mandatory page charge to help defray a portion of the costs of publishing the manuscript. Instructions for Authors are available online on the journal’s website (www.eaglehill.us/cana). -

Tree Swallow in Scilly: New to the Western Palearctic Jeremy Hickman

Tree Swallow in Scilly: new to the Western Palearctic Jeremy Hickman The Isles of Scilly is renowned as a haven for displaced migrant birds, and the autumn pilgrimage of observers in September and October is famous in ornithological circles. June is usually a quiet month for numbers of visiting birdwatchers, as are the other months outside the autumn, but June 1990 was the exception. In one five-day period, between 800 and 1,000 people came to see one bird: the first record for Britain & Ireland, Europe and the Western Palearctic of a North American species, Tree Swallow Tachycineta bicolor. On Wednesday 6th June 1990, having finished my shift behind the bar in the Mermaid Inn, I decided to go to Porth Hellick. I watched from the main hide for a while and could hardly believe how devoid of bird life it was. I could not even console myself by counting the Moorhens Gallinula chloropus. At about 19.00 BST, five hirundines approached low over the pool: one House Martin Delichon urbica, three Barn Swallows Hirundo rustica and another bird. This fifth bird gave the impression of a martin, but with no white rump and a glossy blue-green mantle and crown, and pure white underparts. My heart sank as the bird then flew to the back of the pool and began hawking around the pines and surrounding fields. I rushed to Sluice to obtain closer views and to note its plumage in detail. It appeared slightly bigger and bulkier in the body than a House Martin, with broader-based wings and more powerful flight.