Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Using Intervention Mapping to Develop a Digital Self-Management Program for People with Type 2 Diabetes: Tutorial on Mydesmond

JOURNAL OF MEDICAL INTERNET RESEARCH Hadjiconstantinou et al Tutorial Using Intervention Mapping to Develop a Digital Self-Management Program for People With Type 2 Diabetes: Tutorial on MyDESMOND Michelle Hadjiconstantinou1, BSc, MSc, PhD, CPsychol; Sally Schreder2, MSc; Christopher Brough2, BSc; Alison Northern2; Bernie Stribling2, MBA; Kamlesh Khunti1, MBChB, PhD, MD, FRCGP, DCH, DRCOG; Melanie J Davies1, MB, ChB, MD, FRCP, FRCGP 1Diabetes Research Centre, University of Leicester, Leicester, United Kingdom 2Leicester Diabetes Centre, NHS Trust, University Hospitals of Leicester, Leicester, United Kingdom Corresponding Author: Sally Schreder, MSc Leicester Diabetes Centre NHS Trust University Hospitals of Leicester Gwendolen Road Leicester United Kingdom Phone: 44 116 258 4320 Email: [email protected] Abstract Digital health interventions (DHIs) are increasingly becoming integrated into diabetes self-management to improve behavior. Despite DHIs becoming available to people with chronic conditions, the development strategies and processes undertaken are often not well described. With theoretical frameworks available in current literature, it is vital that DHIs follow a shared language and communicate a robust development process in a comprehensive way. This paper aims to bring a unique perspective to digital development, as it describes the systematic process of developing a digital self-management program for people with type 2 diabetes, MyDESMOND. We provide a step-by-step guide, based on the intervention mapping (IM) framework -

The Prediction of Clinical Outcome Using Hba1c in Acute Ischemic

Original Article Ann Rehabil Med 2015;39(6):1011-1017 pISSN: 2234-0645 • eISSN: 2234-0653 http://dx.doi.org/10.5535/arm.2015.39.6.1011 Annals of Rehabilitation Medicine The Prediction of Clinical Outcome Using HbA1c in Acute Ischemic Stroke of the Deep Branch of Middle Cerebral Artery Sung Bong Shin, MD1, Tae Uk Kim, MD, PhD1, Jung Keun Hyun, MD, PhD1,2,3, Jung Yoon Kim, MD, PhD1,4 1Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Dankook University College of Medicine, Cheonan; 2Department of Nanobiomedical Science & WCU Research Center, Dankook University, Cheonan; 3Institute of Tissue Regeneration Engineering (ITREN), Dankook University, Cheonan; 4Ewha Brain Institute, Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Korea Objective To elucidate the association between glycemic control status and clinical outcomes in patients with acute ischemic stroke limited to the deep branch of the middle cerebral artery (MCA). Methods We evaluated 65 subjects with first-ever ischemic stroke of the deep branches of the MCA, which was confirmed by magnetic resonance angiography. All subjects had blood hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) measured at admission. They were classified into two groups according to the level of HbA1c (low <7.0% or high ≥7.0%). Neurological impairment and functional status were evaluated using the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS), Functional Independence Measure (FIM), Korean version of Modified Barthel Index (K-MBI), Korean version of Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE-K), and the Loewenstein Occupational Therapy Cognitive Assessment (LOTCA) at admission and discharge. Body mass index, serum glucose, homocysteine and cholesterol levels were also measured at admission. Results The two groups did not show any difference in the NIHSS, FIM, K-MBI, MMSE-K, and LOTCA scores at any time point. -

Prevention of Diabetic Foot Complications

Singapore Med J 2018; 59(6): 291-294 Commentary https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2018069 Prevention of diabetic foot complications Aziz Nather1, FRCSE, Shuo Cao1, Jamie Li Wen Chen1, An Yee Low1 ABSTRACT This paper discussed the importance of prevention of diabetic foot ulcers and our institution’s protocol for prevention, reviewing the existing evidence in the literature regarding the effectiveness of the preventive approach. Diabetes mellitus is the second most significant cause of disease in Singapore after ischaemic heart disease. National University Hospital, Singapore, adopts a two-pronged strategy for the management of diabetic foot ulcers. The most important strategy is prevention, and education is key. Education should mainly be directed at patients and caregivers, but also professionals (general practitioners, allied health professionals and nurses) so that they can effectively educate patients and caregivers. Patient education includes care of diabetes mellitus, care of the foot and use of appropriate footwear. Patients also tend to have poor foot hygiene. Annual foot screening for diagnosed diabetics plays an important role. However, prolonged and sustained government intervention is necessary to provide education and screening on a national scale. Keywords: annual foot screening, care of diabetes, care of foot and choice of footwear, education, prevention of diabetic foot wounds INTRODUCTION screening are required to prevent diabetic foot problems, with the Diabetes mellitus is on the rise in Singapore. It is now the second help of government intervention to run education and screening most significant cause of ill-health and disease in Singapore after programmes on a national scale. Our institution, the National ischaemic heart disease, affecting one in nine Singaporeans. -

Type 2 Diabetes Guidelines

Type 2 Diabetes Guidelines Version 4 Revised September 2012 for the DECENT Network Diabetes Education Care & Evaluation North of the Tees Covering the Stockton on Tees, Hartlepool and Easington areas Type 2 Diabetes Guidelines for the DECENT Network 1 NICE Diabetes in adults Quality Standards of Care 2011 1. People with diabetes and/or their carers receive a structured educational programme that fulfils the nationally agreed criteria from the time of diagnosis, with annual review and access to ongoing education. 2. People with diabetes receive personalised advice on nutrition and physical activity from an appropriately trained healthcare professional or as part of a structured educational programme. 3. People with diabetes participate in annual care planning which leads to documented agreed goals and an action plan. 4. People with diabetes agree with their healthcare professional a documented personalised HbA1c target, usually between 48 mmol/mol and 58 mmol/mol, and receive an ongoing review of treatment to minimise hypoglycaemia. 5. People with diabetes agree with their healthcare professional to start, review and stop medications to lower blood glucose, blood pressure and blood lipids in accordance with NICE guidance. 6. Trained healthcare professionals initiate and manage therapy with insulin within a structured programme that includes dose titration by the person with diabetes. 7. Women of childbearing age with diabetes are regularly informed of the benefits of preconception glycaemic control and of any risks, including medication that may harm an unborn child. Women with diabetes planning a pregnancy are offered preconception care and those not planning a pregnancy are offered advice on contraception. -

Dynamic Hyperglycemic Patterns Predict Adverse Outcomes in Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke Undergoing Mechanical Thrombectomy

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article Dynamic Hyperglycemic Patterns Predict Adverse Outcomes in Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke Undergoing Mechanical Thrombectomy 1,2, , 2,3, 4 2,5 Giovanni Merlino * y , Carmelo Smeralda y , Massimo Sponza , Gian Luigi Gigli , Simone Lorenzut 1, Alessandro Marini 2,3 , Andrea Surcinelli 2,3, Sara Pez 2,3, Alessandro Vit 4, Vladimir Gavrilovic 4 and Mariarosaria Valente 2,3 1 Stroke Unit, Department of Neuroscience, Udine University Hospital, 33100 Udine, Italy; [email protected] 2 Clinical Neurology, Udine University Hospital, 33100 Udine, Italy; [email protected] (C.S.); [email protected] (G.L.G.); [email protected] (A.M.); [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (S.P.); [email protected] (M.V.) 3 DAME, University of Udine, 33100 Udine, Italy 4 Division of Vascular and Interventional Radiology, Udine University Hospital, 33100 Udine, Italy; [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (A.V.); [email protected] (V.G.) 5 DMIF, University of Udine, 33100 Udine, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-043-255-2720 These authors contributed equally to this study. y Received: 5 May 2020; Accepted: 18 June 2020; Published: 20 June 2020 Abstract: Background: Admission hyperglycemia impairs outcome in acute ischemic stroke (AIS) patients undergoing mechanical thrombectomy (MT). Since hyperglycemia in AIS represents a dynamic condition, we tested whether the dynamic patterns of hyperglycemia, defined as blood glucose levels > 140 mg/dl, affect outcomes in these patients. Methods: We retrospectively analyzed data of 200 consecutive patients with prospective follow-up. -

Secular Changes in U.S. Prediabetes Prevalence Defined by Hemoglobin

Epidemiology/Health Services Research ORIGINAL ARTICLE Secular Changes in U.S. Prediabetes fi Prevalence De ned by Hemoglobin A1c and Fasting Plasma Glucose National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 1999–2010 1 1 KAI MCKEEVER BULLARD, PHD LINDA S. GEISS, MA 199 mg/dL (impaired glucose tolerance 1 1 SHARON H. SAYDAH, PHD YILING J. CHENG, PHD 1 1 [IGT]), or hemoglobin A1c (A1C) 5.7 to GIUSEPPINA IMPERATORE, MD, PHD DEBORAH B. ROLKA, MS , , 2 1 6.5% (39 to 48 mmol/mol) (2). In CATHERINE C. COWIE, PHD DESMOND E. WILLIAMS, MD, PHD 1 1 2010, 79 million U.S. adults had predia- EDWARD W. GREGG, PHD CARL J. CASPERSEN, PHD, MPH betesbasedonIFGorelevatedA1Ccrite- ria (1). Fortunately, the Diabetes Prevention Program of the National Institutes of OBJECTIVEdUsing a nationally representative sample of the civilian noninstitutionalized U.S. population, we estimated prediabetes prevalence and its changes during 1999–2010. Health and other studies have shown that among adults with elevated glucose RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODSdData were from 19,182 nonpregnant individ- levels, type 2 diabetes can be delayed or uals aged $12 years who participated in the 1999–2010 National Health and Nutrition Exam- prevented (3–6). Further, recent studies fi , , ination Surveys. We de ned prediabetes as hemoglobin A1c 5.7 to 6.5% (39 to 48 mmol/mol, have shown that effective lifestyle-based , A1C5.7) or fasting plasma glucose (FPG) 100 to 126 mg/dL (impaired fasting glucose [IFG]). interventions can be successfully imple- We estimated the prevalence of prediabetes, A1C5.7, and IFG for 1999–2002, 2003–2006, and – mented in community-based settings 2007 2010. -

OBSERVATIONS Athy

LETTERS 1 liferative or proliferative diabetic retinop- ATSUSHI MINAMOTO, PHD 3 OBSERVATIONS athy. Data are presented as means Ϯ SD. HIDEHARU FUNATSU, PHD 4 The Mann-Whitney U test was used to HIDETOSHI YAMASHITA, PHD ␣ 5 compare IL-6 and TNF- levels. To deter- SHIGEO NAKAMURA, PHD 4 mine the relationship between the sever- KEN KIRIYAMA, PHD 5 Relationship ity of periodontal disease and ETDRS, HIDEMI KURIHARA, PHD 1 retinopathy severity, or angiogenic fac- HIROMU K. MISHIMA, PHD Between Periodontal tors, as well as between X and Y parame- Disease and Diabetic ters, Spearman’s rank-order correlation Retinopathy coefficient and logistic regression model From the 1Department of Ophthalmology and Vi- were applied. sual Science, Hiroshima University Graduate School The severity of periodontal disease of Biomedical Sciences, Hiroshima, Japan; the 2De- was significantly correlated with the se- partment of Ophthalmology, Hiroshima Prefectural ecently, various studies have re- verity of diabetic retinopathy (P ϭ Hospital, Hiroshima, Japan; the 3Department of ported that periodontal disease ad- 0.0012), and the risk of proliferative dia- Ophthalmology, Diabetes Center, Tokyo Women’s Medical University, Tokyo, Japan; the 4Department versely affects diabetes (1). The betic retinopathy was significantly higher R of Ophthalmology and Visual Science, Yamagata control of periodontal disease in elderly in the presence of periodontal disease ϭ ϭ University School of Medicine, Yamagata, Japan; individuals has been reported to improve (odds ratio 2.80, P 0.036). There and the 5Department of Periodontal Medicine, Hi- the control of blood glucose (2). Severe was no significant relationship between roshima University Graduate School of Biomedical periodontal disease is associated with el- the severity of periodontal disease and Sciences, Hiroshima, Japan. -

Influence of Diabetes- Related Knowledge on Foot Ulceration

Influence of diabetes- related knowledge on foot ulceration Cynthia Formosa, Lourdes Vella Article points To investigate the relationship between diabetes-related knowledge 1. This study aimed to and foot ulceration among people with type 2 diabetes, the authors explore the relationship assessed diabetes knowledge in groups with and without foot between diabetes-related knowledge and foot ulceration. There was no significant difference in diabetes-related ulceration in a Maltese knowledge between the two groups, although the mean level of population with type 2 knowledge in the group with foot ulceration was greater. The authors’ diabetes. question current approaches to diabetes education and suggest that a 2. No significant difference new approach to diabetes education programmes is needed. in diabetes-related knowledge was found he incidence of diabetes is increasing Strine et al (2005) reported that 50–80% to exist between those worldwide and an estimated 1–4% of people with diabetes worldwide have with and without foot ulceration. T of people with type 2 diabetes significant knowledge deficits in relation to develop a foot ulcer each year (Boulton et al, the management of their condition. These 3. Diabetic foot ulcers are 2005). This is of concern for both people data suggest that people are either not a global concern leading with diabetic foot ulceration and healthcare receiving diabetes education, or that the to patient morbidity and mortality, and providers, with episodes of ulceration strongly education offered is not effective. A fuller improvements in the associated with lower-extremity amputations, understanding of the factors that contribute approach to diabetes reduced quality of life, long periods of to suboptimal self-management, leading education may improve hospitalisation and substantial healthcare ultimately to distressing and costly diabetic outcomes. -

Designed for the Management of Adults with Diabetes Mellitus Across Wales: Consensus Guidelines

Designed for the Management of Adults with Diabetes Mellitus across Wales: Consensus Guidelines To Support Implementation of the Diabetes National Service Framework for Wales Quality Requirements October 2008 ISBN 978 0 7504 4731 7 © Crown copyright, October 2008 CMK-12-128 D0800809 Ministerial Foreword The Welsh Assembly Government has shown commitment to people with diabetes across Wales by supporting many initiatives in the promotion and implementation of the Delivery Strategy of the National Service Framework for Diabetes in Wales. The Standards were launched in April 2002 and the Delivery Strategy in March 2003. In 2003 the estimated prevalence of diabetes across Wales was 3.8% and by 2006/7 the prevalence rate recorded from the Quality and Outcomes Framework database had increased to 4.18%. It is estimated that there are 50,000 people with diabetes who remain undiagnosed in Wales. The Delivery Strategy set the foundation for the planning and implementation of the 12 Standards of care and includes Action Plans designed to raise standards of diabetes care in Wales. Although some areas in Wales have developed their own local Management Guidelines many health professionals have requested All Wales Consensus Guidelines for the management of diabetes. The All Wales Consensus Group - health care professionals working in partnership with people with diabetes, their carers, voluntary organisations and service users - have been responsible for the development of these Guidelines designed to provide support and to improve diabetes care across Wales. Implementation of the Consensus Guidelines will assist in • the planning of services; • improved quality of services; • reducing inequalities in diabetes care across Wales. -

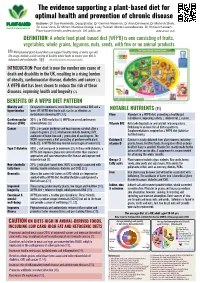

The Evidence Supporting a Plant-Based Diet for Optimal Health

The evidence supporting a plant-based diet for optimal health and prevention of chronic disease Authors: Dr Sue Kenneally, Doug Bristor, Dr Gemma Newman, Dr Alan Desmond, Dr Mahesh Shah, Dr Luke Vano, Dr Miriam Martinez-Biarge, Lucy Russell, Marta Lewandowska, Dr Shireen Kassam. Plant-based health professionals, UK (pbhp.uk) Updated April 2020 DEFINITION: A whole food plant-based diet (WFPB) is one consisting of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, seeds, with few or no animal products. Well-planned plant-based diets can support healthy living at every age and life-stage. Include a wide variety of healthy whole foods to ensure your diet is balanced and sustainable. The British Dietetic Association (BDA) INTRODUCTION: Poor diet is now the number one cause of death and disability in the UK, resulting in a rising burden of obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and cancer (1). A WFPB diet has been shown to reduce the risk of these diseases, improving health and longevity (2). BENEFITS OF A WFPB DIET PATTERN Obesity and Compared to omnivores, more likely to have normal BMI and a hypertension lower BP. WFPB diet low in salt, can be as effective as NOTABLE NUTRIENTS (11) medication in lowering BP (3,4). Fibre Abundant in a WFPB diet, promoting a healthy gut ↓ ↓ Cardiovascular 30% ↓ in CVD mortality (5). WFPB can arrest and reverse microbiome, improving satiety, cholesterol, cancer. disease (CVD) atherosclerosis (6). Vitamin B12 Not made by plants or animals but microorganisms. Cancer 15% ↓ in cancer incidence and may improve survival after a Deficiency is an issue for all dietary patterns. -

Association of Baseline Hyperglycemia with Outcomes Of

Diabetes Volume 68, September 2019 1861 Association of Baseline Hyperglycemia With Outcomes of Patients With and Without Diabetes With Acute Ischemic Stroke Treated With Intravenous Thrombolysis: A Propensity Score–Matched Analysis From the SITS-ISTR Registry Georgios Tsivgoulis,1,2 Aristeidis H. Katsanos,1,3 Dimitris Mavridis,4,5 Vaia Lambadiari,6 Christine Roffe,7 Mary Joan Macleod,8 Petr Sevcik,9 Manuel Cappellari,10 Miroslava Nevšímalová,11 Danilo Toni,12 and Niaz Ahmed13,14 Diabetes 2019;68:1861–1869 | https://doi.org/10.2337/db19-0440 Available data from observational studies on the asso- with patients without aHG. Similarly, in the DM group, ciation of admission hyperglycemia (aHG) with outcomes patients with aHG had lower rates of 3-month favor- COMPLICATIONS of patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS) treated with able functional outcome (mRS scores 0–1, 34.1% vs. intravenous thrombolysis (IVT) are contradictory, espe- 39.3%, P < 0.001) and FI (48.2% vs. 52.5%, P < 0.001), cially when stratified by diabetes mellitus (DM) history. higher 3-month mortality rates (23.7% vs. 19.9%, P < We assessed the association of aHG (‡144 mg/dL) with 0.001), and similar SICH rates (2.2% vs. 2.7%, P = 0.224) outcomes stratified by DM history using propensity compared with patients without aHG. In conclusion, aHG score–matched (PSM) data from the SITS-ISTR. The was associated with unfavorable 3-month clinical out- primary safety outcome was symptomatic intracranial comes in patients with and without DM and AIS treated hemorrhage (SICH); 3-month functional independence with IVT. -

Managing Diabetic Foot Ulcers

Review Review MANAGING DIABETIC FOOT ULCERS: BEST PRACTICE Despite a wealth of evidence and clinical guidelines, the prevention and management of diabetic foot ulcers remains a challenge. This article aims to defi ne best practice through the exploration of ten key points taken from current evidence and guidelines in an attempt to help non-specialist practitioners to implement best practice when treating patients with diabetes. Caroline McIntosh and Veronica Newton are Senior Lecturers in Podiatry, University of Huddersfi eld The need for standardised care in diabetes has been highlighted by the development of numerous clinical guidelines and best practice statements from key sources such as the National Institute for Health Figure 1. Diabetic foot and Clinical Excellence (NICE, ulcer. 2004); the Department of Health (Dept of Health, 2001); the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, (SIGN, 2001), and the Royal College to have an appreciation of the characterised by chronic of General Practitioners underlying disease process. hyperglycaemia. (Hutchinson et al, 2000) (Table 1). New evidence is constantly Diabetes mellitus occurs when There are two main types of emerging within the field there is inadequate uptake of diabetes: type 1 and type of diabetes care, making it glucose by the cells of the body 2. In people with type 1 difficult for the non-specialist resulting in raised blood glucose diabetes, the pancreas does practitioner to remain up-to- levels (Pocock and Richards, not produce enough insulin. date with current best evidence. 2004). This is an autoimmune disease This review aims to identify the whereby the insulin producing basic requirements of diabetic Insulin, a hormone produced β-cells are destroyed by the foot examination and to define in the pancreas, regulates the body’s own immune system.