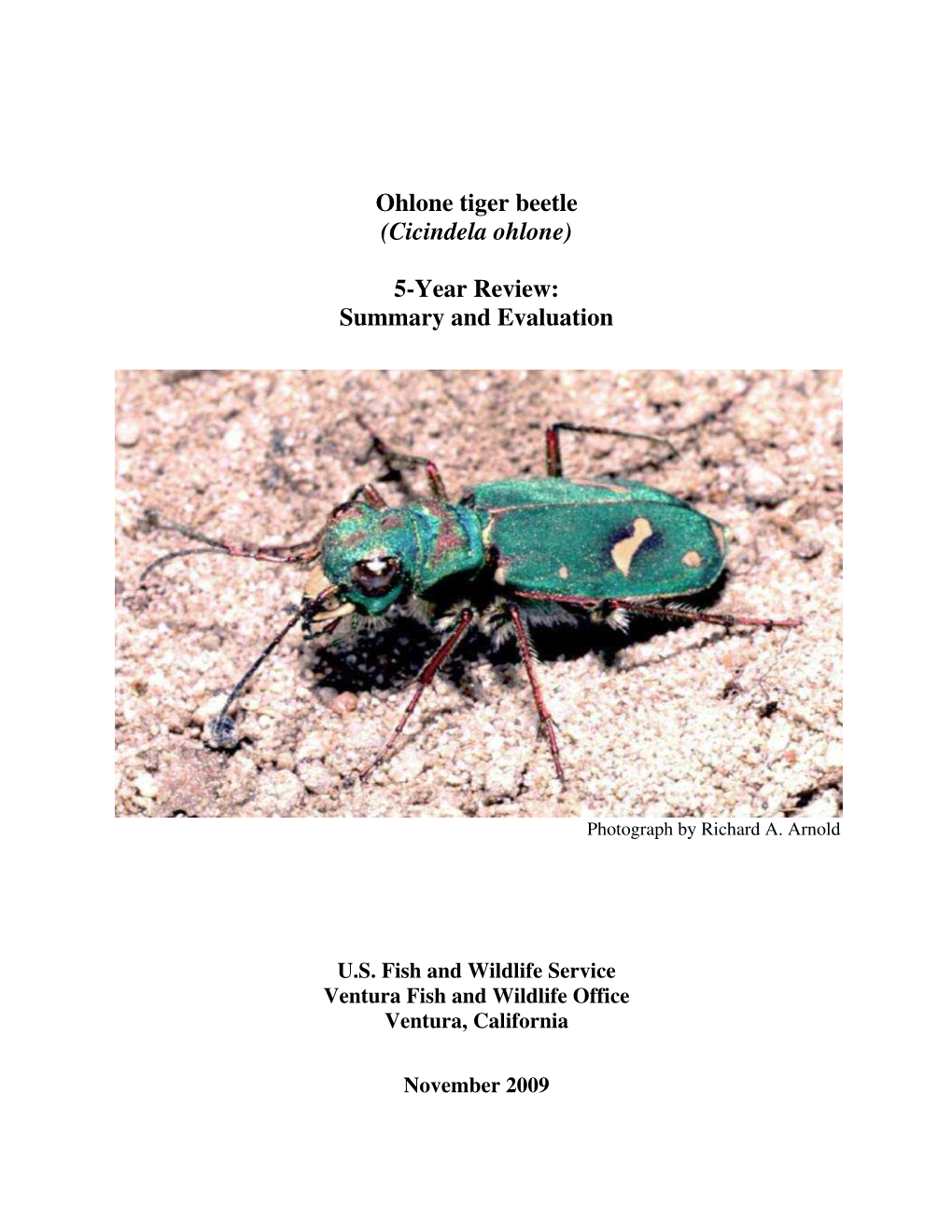

Ohlone Tiger Beetle (Cicindela Ohlone) 5-Year Review: Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northeastern Beach Tiger Beetle (Cicindela Dorsalis Dorsalis)

Northeastern Beach Tiger Beetle (Cicindela dorsalis dorsalis) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation u.s. Fish and Wildlife Service Virginia Field Office Gloucester, Virginia February 2009 5-YEAR REVIEW Species reviewed: Northeastern beach tiger beetle (Cicindela dorsalis dorsalis) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 GENERAL INFORMATION ...................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Reviewers........................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Methodology .................................................................................................................. 1 1.3 Background ..................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 REVIEW ANALYSIS 2.1 Application of 1996 Distinct Population Segment (DPS) Policy ................................... 2 2.2 Recovery Criteria ............................................................................................................ 2 2.3 Updated Information and Current Species Status ........................................................... 5 2.3.1 Biology and habitat .............................................................................................. 5 2.3.2 Five-factor analysis .............................................................................................. 10 2.4 Synthesis .........................................................................................................................13 -

AEXT Ucsu2062256012007.Pdf (677.1Kb)

I N S E C T S E R I E S HOME & GARDEN Japanese Beetle no. 5.601 by W. Cranshaw1 The Japanese beetle, Popillia japonica, can be a very damaging insect in both the adult and larval stages. Larvae Quick Facts... chew roots of turfgrasses and it is the most important white grub pest of turfgrass in much of the northeastern quadrant Adult Japanese beetles cause of the United States. Adults also cause serious injury to leaves and serious injuries as they feed on the leaves flowers of many ornamentals, and flowers of many ornamentals, fruits, fruits, and vegetables. Among and vegetables. Among the plants most Figure 1. Japanese beetle. Photo the plants most commonly commonly damaged are rose, grape, courtesy of David Cappaert. damaged are rose, grape, crabapple, and beans. crabapple, and beans. Japanese beetle is also a regulated insect subject to internal quarantines in the United States. The presence of established Japanese beetle populations There are many insects in in Colorado restricts trade. Nursery products originating from Japanese beetle- Colorado that may be mistaken infested states require special treatment or are outright banned from shipment to for Japanese beetle. areas where this insect does not occur. To identify Japanese beetle Current Distribution of the Japanese Beetle consider differences in size, From its original introduction in New Jersey in 1919, Japanese beetle has shape and patterning. greatly expanded its range. It is now generally distributed throughout the country, excluding the extreme southeast. It is also found in parts of Ontario, Canada. Japanese beetle is most commonly transported to new locations with soil surrounding nursery plants. -

Ants As Prey for the Endemic and Endangered Spanish Tiger Beetle Cephalota Dulcinea (Coleoptera: Carabidae) Carlo Polidori A*, Paula C

Annales de la Société entomologique de France (N.S.), 2020 https://doi.org/10.1080/00379271.2020.1791252 Ants as prey for the endemic and endangered Spanish tiger beetle Cephalota dulcinea (Coleoptera: Carabidae) Carlo Polidori a*, Paula C. Rodríguez-Flores b,c & Mario García-París b aInstituto de Ciencias Ambientales (ICAM), Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, Avenida Carlos III, S/n, 45071, Toledo, Spain; bDepartamento de Biodiversidad y Biología Evolutiva, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (MNCN-CSIC), Madrid, 28006, Spain; cCentre d’Estudis Avançats de Blanes (CEAB-CSIC), C. d’Accés Cala Sant Francesc, 14, 17300, Blanes, Spain (Accepté le 29 juin 2020) Summary. Among the insects inhabiting endorheic, temporary and highly saline small lakes of central Spain during dry periods, tiger beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Cicindelinae) form particularly rich assemblages including unique endemic species. Cephalota dulcinea López, De la Rosa & Baena, 2006 is an endemic, regionally protected species that occurs only in saline marshes in Castilla-La Mancha (Central Spain). Here, we report that C. dulcinea suffers potential risks associated with counter-attacks by ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), while using them as prey at one of these marshes. Through mark–recapture methods, we estimated the population size of C. dulcinea at the study marsh as of 1352 individuals, with a sex ratio slightly biased towards males. Evident signs of ant defensive attack by the seed-harvesting ant Messor barbarus (Forel, 1905) were detected in 14% of marked individuals, sometimes with cut ant heads still grasped with their mandibles to the beetle body parts. Ant injuries have been more frequently recorded at the end of adult C. -

Rare Native Animals of RI

RARE NATIVE ANIMALS OF RHODE ISLAND Revised: March, 2006 ABOUT THIS LIST The list is divided by vertebrates and invertebrates and is arranged taxonomically according to the recognized authority cited before each group. Appropriate synonomy is included where names have changed since publication of the cited authority. The Natural Heritage Program's Rare Native Plants of Rhode Island includes an estimate of the number of "extant populations" for each listed plant species, a figure which has been helpful in assessing the health of each species. Because animals are mobile, some exhibiting annual long-distance migrations, it is not possible to derive a population index that can be applied to all animal groups. The status assigned to each species (see definitions below) provides some indication of its range, relative abundance, and vulnerability to decline. More specific and pertinent data is available from the Natural Heritage Program, the Rhode Island Endangered Species Program, and the Rhode Island Natural History Survey. STATUS. The status of each species is designated by letter codes as defined: (FE) Federally Endangered (7 species currently listed) (FT) Federally Threatened (2 species currently listed) (SE) State Endangered Native species in imminent danger of extirpation from Rhode Island. These taxa may meet one or more of the following criteria: 1. Formerly considered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for Federal listing as endangered or threatened. 2. Known from an estimated 1-2 total populations in the state. 3. Apparently globally rare or threatened; estimated at 100 or fewer populations range-wide. Animals listed as State Endangered are protected under the provisions of the Rhode Island State Endangered Species Act, Title 20 of the General Laws of the State of Rhode Island. -

Federal Register / Vol. 61, No. 42 / Friday, March 1, 1996 / Proposed

8014 Federal Register / Vol. 61, No. 42 / Friday, March 1, 1996 / Proposed Rules under CERCLA are appropriate at this FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: is currently known only from Santa time. Consequently, U.S EPA proposed Leslie K. Shapiro, Mass Media Bureau, Cruz County, California. The five known to delete the site from the NPL. (202) 418±2180. populations may be threatened by the EPA, with concurrence from the State SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: This is a following factors: habitat fragmentation of Minnesota, has determined that all synopsis of the Commission's Notice of and destruction due to urban appropriate Fund-financed responses Proposed Rule Making, MM Docket No. development, habitat degradation due to under CERCLA at the Kummer Sanitary 96±19, adopted February 6, 1996, and invasion of non-native vegetation, and Landfill Superfund Site have been released February 20, 1996. The full text vulnerability to stochastic local completed, and no further CERCLA of this Commission decision is available extirpations. However, the Service finds response is appropriate in order to for inspection and copying during that the information presented in the provide protection of human health and normal business hours in the FCC petition, in addition to information in the environment. Therefore, EPA Reference Center (Room 239), 1919 M the Service's files, does not provide proposes to delete the site from the NPL. Street, NW., Washington, DC. The conclusive data on biological vulnerability and threats to the species Dated: February 20, 1996. complete text of this decision may also be purchased from the Commission's and/or its habitat. Available information Valdas V. -

Proposed Endangered Status for the Ohlone Tiger Beetle

6952 Federal Register / Vol. 65, No. 29 / Friday, February 11, 2000 / Proposed Rules For further information, please confirmation from the system that we oviposition (egg laying) (Pearson 1988). contact: Chris Murphy, Satellite Policy have received your e-mail message, It is not known at this time how many Branch, (202) 418±2373, or Howard contact us directly by calling our eggs the Ohlone tiger beetle female lays, Griboff, Satellite Policy Branch, at (202) Carlsbad Fish and Wildlife Office at but other species of Cicindela are 418±0657. phone number 805/644±1766. known to lay between 1 and 14 eggs per (3) You may hand-deliver comments female (mean range 3.7 to 7.7), List of Subjects in 47 CFR Part 25 to our Ventura Fish and Wildlife Office, depending on the species (Kaulbars and Satellites. 2493 Portola Road, Suite B, Ventura, Freitag 1993). After the larva emerges Federal Communications Commission. California 93003. from the egg and becomes hardened, it Anna M. Gomez, FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: enlarges the chamber that contained the Deputy Chief, International Bureau. Colleen Sculley, invertebrate biologist, egg into a tunnel (Pearson 1988). Before pupation (transformation process from [FR Doc. 00±3332 Filed 2±10±00; 8:45 am] Ventura Fish and Wildlife Office, at the larva to adult), the third instar larva will BILLING CODE 6712±01±P above address (telephone 805/644±1766; facsimile 805/644±3958). plug the burrow entrance and dig a SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: chamber for pupation. After pupation, the adult tiger beetle will dig out of the DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Background soil and emerge. -

Recovery Plan for Northeastern Beach Tiger Beetle

Northeastern Beach Tiger Beetle, (Cincindela dorsalisdorsal/s Say) t1rtmow RECOVERY PLAN 4.- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service SFAVI ? Hadley, Massachusetts September 1994 C'AZ7 r4S \01\ Cover illustration by Katherine Brown-Wing copyright 1993 NORTHEASTERN BEACH TIGER BEETLE (Cicindela dorsalis dorsalis Say) RECOVERY PLAN Prepared by: James M. Hill and C. Barry Knisley Department of Biology Randolph-Macon College Ashland, Virginia in cooperation with the Chesapeake Bay Field Office U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and members of the Tiger Beetle Recovery Planning-Group Approved: . ILL Regi Director, Region Five U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Date: 9 29- ~' TIGER BEETLE RECOVERY PLANNING GROUP James Hill Philip Nothnagle Route 1 Box 2746A RFD 1, Box 459 Reedville, VA Windsor, VT 05089 Judy Jacobs Steve Roble U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service VA Natural Heritage Program Annapolis Field Office Main Street Station 177 Admiral Cochrane Drive 1500 East Main Street Annapolis, MD 21401 Richmond, VA 23219 C. Barry Knisley Tim Simmons Biology Department The Nature Conservancy Massachusetts Randolph-Macon College Field Office Ashland, VA 23005 79 Milk Street Suite 300 Boston, MA 02109 Laurie MacIvor The Nature Conservancy Washington Monument State Park 6620 Monument Road Middletown, MD 21769 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY NORTHEASTERN BEACH TIGER BEETLE RECOVERY PLAN Current Status: This tiger beetle occurred historically "in great swarms" on beaches along the Atlantic Coast, from Cape Cod to central New Jersey, and along Chesapeake Bay beaches in Maryland and Virginia. Currently, only two small populations remain on the Atlantic Coast. The subspecies occurs at over 50 sites within the Chesapeake Bay region. -

Beetle (Cicindela Albissima)

AMENDMENT TO THE 2009 CONSERVATION AGREEMENT AND STRATEGY FOR THE CORAL PINK SAND DUNES TIGER BEETLE (CICINDELA ALBISSIMA) March 2013 Prepared by the Conservation Committee for the Coral Pink Sand Dunes Tiger Beetle BACKGROUND Initially formalized in 1997 (Conservation Committee 1997, entire), and revised in 2009 (Conservation Committee 2009, entire) , the Conservation Agreement for the Coral Pink Sand Dunes Tiger Beetle (CCA) is a partnership for the development and implementation of conservation measures to protect the tiger beetle and its habitat. The purpose of the partnership is to ensure the long-term persistence of the Coral Pink Sand Dunes tiger beetle within its historic range and provide a framework for future conservation efforts. The Utah Department of Natural Resources, Division of Parks and Recreation, Bureau of Land Management (BLM), U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), and Kane County, Utah, are signatories to these agreements and have implemented conservation actions to benefit the Coral Pink Sand Dunes (CPSD) tiger beetle and its habitat, monitored their effectiveness, and adapted strategies as new information became available. Among other actions, coordination under the CCA resulted in the establishment of two Conservation Areas that protect the Coral Pink Sand Dunes tiger beetle from off-road vehicle (ORV) use—Conservation Areas A and B (77 FR 60208). This amendment to the 2009 CCA outlines several new conservation actions that will be enacted to address the threats that were identified in the USFWS October 2, 2012 proposed rule (77 FR 60208). This amendment evaluated the most recent tiger beetle survey information (Knisley and Gowan 2013) and concluded that modifications to the boundaries of the Conservation Areas are needed to ensure continued protection of the tiger beetle from ongoing threats (see below description of threats). -

The Occurrence of the Endemic Tiger Beetle Cicindela (Ifasina) Waterhousei in Bopath Ella, Ratnapura

J.Natn.Sci.Foundation Sri Lanka 2011 39 (2): 163-168 SHORT COMMUNICATION The occurrence of the endemic tiger beetle Cicindela (Ifasina) waterhousei in Bopath Ella, Ratnapura Chandima Dangalle 1* , Nirmalie Pallewatta 1 and Alfried Vogler 2 1 Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, University of Colombo, Colombo 03. 2 Department of Entomology, The Natural History Museum, London SW7 5BD, United Kingdom. Revised: 04 January 2011 ; Accepted: 21 January 2011 Abstract: The occurrence of the endemic tiger beetle Cicindela species are found in the Oriental region of the world in (Ifasina) waterhousei from Bopath Ella, Ratnapura is recorded countries such as Malaysia, Indonesia, Japan and China for the first time. The study reveals a population of 276 beetles (Pearson, 1988). Fifty-six species have been recorded from the sandy bank habitat of Bopath Ella. A site description from Sri Lanka of which thirty-five species are said to be is given stating the abiotic environmental factors of climate and endemic to the island (Cassola & Pearson, 2000). soil. Morphology of the species is described using diagnostic features of the genus, and in comparison with reference specimens at the Department of National Museums, Colombo Cicindela (Ifasina) waterhousei Horn is endemic and the type specimen at the British Natural History Museum, to Sri Lanka and has been recorded along watercourses London. According to the findings of the study, at present, within dark, moist forests of Labugama (Colombo the species is recorded only from Bopath Ella and is absent District, Western Province), Avissawella (Colombo from its previously recorded locations at Labugama, Kitulgala, District, Western Province), Kitulgala (Kegalle District, Karawanella and Avissawella. -

This Work Is Licensed Under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. THE TIGER BEETLES OF ALBERTA (COLEOPTERA: CARABIDAE, CICINDELINI)' Gerald J. Hilchie Department of Entomology University of Alberta Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2E3. Quaestiones Entomologicae 21:319-347 1985 ABSTRACT In Alberta there are 19 species of tiger beetles {Cicindela). These are found in a wide variety of habitats from sand dunes and riverbanks to construction sites. Each species has a unique distribution resulting from complex interactions of adult site selection, life history, competition, predation and historical factors. Post-pleistocene dispersal of tiger beetles into Alberta came predominantly from the south with a few species entering Alberta from the north and west. INTRODUCTION Wallis (1961) recognized 26 species of Cicindela in Canada, of which 19 occur in Alberta. Most species of tiger beetle in North America are polytypic but, in Alberta most are represented by a single subspecies. Two species are represented each by two subspecies and two others hybridize and might better be described as a single species with distinct subspecies. When a single subspecies is present in the province morphs normally attributed to other subspecies may also be present, in which case the most common morph (over 80% of a population) is used for subspecies designation. Tiger beetles have always been popular with collectors. Bright colours and quick flight make these beetles a sporting and delightful challenge to collect. -

Insects and Related Arthropods Associated with of Agriculture

USDA United States Department Insects and Related Arthropods Associated with of Agriculture Forest Service Greenleaf Manzanita in Montane Chaparral Pacific Southwest Communities of Northeastern California Research Station General Technical Report Michael A. Valenti George T. Ferrell Alan A. Berryman PSW-GTR- 167 Publisher: Pacific Southwest Research Station Albany, California Forest Service Mailing address: U.S. Department of Agriculture PO Box 245, Berkeley CA 9470 1 -0245 Abstract Valenti, Michael A.; Ferrell, George T.; Berryman, Alan A. 1997. Insects and related arthropods associated with greenleaf manzanita in montane chaparral communities of northeastern California. Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-167. Albany, CA: Pacific Southwest Research Station, Forest Service, U.S. Dept. Agriculture; 26 p. September 1997 Specimens representing 19 orders and 169 arthropod families (mostly insects) were collected from greenleaf manzanita brushfields in northeastern California and identified to species whenever possible. More than500 taxa below the family level wereinventoried, and each listing includes relative frequency of encounter, life stages collected, and dominant role in the greenleaf manzanita community. Specific host relationships are included for some predators and parasitoids. Herbivores, predators, and parasitoids comprised the majority (80 percent) of identified insects and related taxa. Retrieval Terms: Arctostaphylos patula, arthropods, California, insects, manzanita The Authors Michael A. Valenti is Forest Health Specialist, Delaware Department of Agriculture, 2320 S. DuPont Hwy, Dover, DE 19901-5515. George T. Ferrell is a retired Research Entomologist, Pacific Southwest Research Station, 2400 Washington Ave., Redding, CA 96001. Alan A. Berryman is Professor of Entomology, Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164-6382. All photographs were taken by Michael A. Valenti, except for Figure 2, which was taken by Amy H. -

Status and Conservation of an Imperiled Tiger Beetle Fauna in New York State, USA

J Insect Conserv (2011) 15:839–852 DOI 10.1007/s10841-011-9382-y ORIGINAL PAPER Status and conservation of an imperiled tiger beetle fauna in New York State, USA Matthew D. Schlesinger • Paul G. Novak Received: 29 October 2010 / Accepted: 17 January 2011 / Published online: 15 February 2011 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2011 Abstract New York has 22 documented species of tiger Introduction beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae). Over half of these species are considered rare, at risk, or potentially extirpated Tiger beetles (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) are strikingly from the state. These rare species specialize on three sandy patterned, predatory insects that have captured the attention habitat types under threat from human disturbance: bea- of entomologists and collectors for centuries. Beyond their ches, pine barrens, and riparian cobble bars. In 2005, we intrinsic interest, tiger beetles can serve as model organ- began a status assessment of eight of New York’s rarest isms or indicator species to enable broad conclusions about tiger beetles, examining museum records, searching the a region or ecosystem’s biodiversity (Pearson and Cassola literature, and conducting over 130 field surveys of his- 1992; Pearson and Vogler 2001). Tiger beetles are threa- torical and new locations. Significant findings included (1) tened by habitat destruction and modification, alteration of no detections of four of the eight taxa; (2) no vehicle-free natural processes like fire and flooding, and overcollection; beach habitat suitable for reintroducing Cicindela dorsalis across the United States, approximately 15% of taxa are dorsalis; (3) C. hirticollis at only 4 of 26 historical loca- threatened with extinction (Pearson et al.