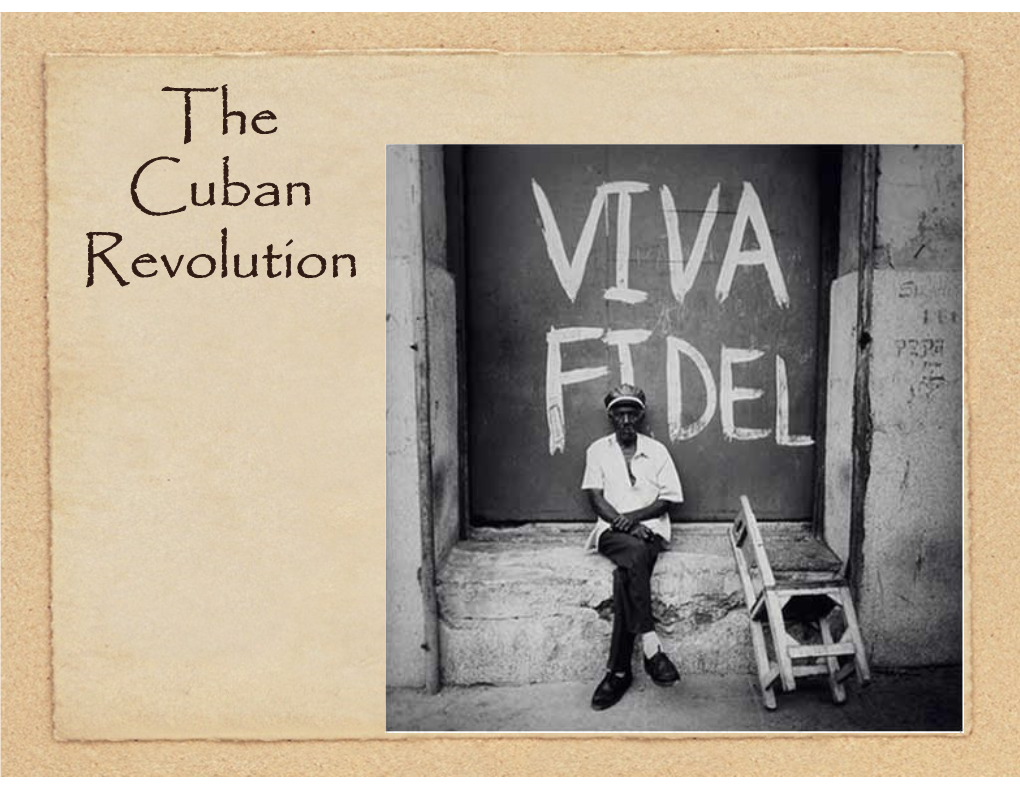

The Cuban Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overview Print Page Close Window

World Directory of Minorities Americas MRG Directory –> Cuba –> Cuba Overview Print Page Close Window Cuba Overview Environment Peoples History Governance Current state of minorities and indigenous peoples Environment Cuba is the largest island in the Caribbean. It is located 150 kilometres south of the tip of the US state of Florida and east of the Yucatán Peninsula. On the east, Cuba is separated by the Windward Passage from Hispaniola, the island shared by Haiti and Dominican Republic. The total land area is 114,524 sq km, which includes the Isla de la Juventud (formerly called Isle of Pines) and other small adjacent islands. Peoples Main languages: Spanish Main religions: Christianity (Roman Catholic, Protestant), syncretic African religions The majority of the population of Cuba is 51% mulatto (mixed white and black), 37% white, 11% black and 1% Chinese (CIA, 2001). However, according to the Official 2002 Cuba Census, 65% of the population is white, 10% black and 25% mulatto. Although there are no distinct indigenous communities still in existence, some mixed but recognizably indigenous Ciboney-Taino-Arawak-descended populations are still considered to have survived in parts of rural Cuba. Furthermore the indigenous element is still in evidence, interwoven as part of the overall population's cultural and genetic heritage. There is no expatriate immigrant population. More than 75 per cent of the population is classified as urban. The revolutionary government, installed in 1959, has generally destroyed the rigid social stratification inherited from Spanish colonial rule. During Spanish colonial rule (and later under US influence) Cuba was a major sugar-producing territory. -

Race and Inequality in Cuban Tourism During the 21St Century

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 6-2015 Race and Inequality in Cuban Tourism During the 21st Century Arah M. Parker California State University - San Bernardino Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the Politics and Social Change Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Tourism Commons Recommended Citation Parker, Arah M., "Race and Inequality in Cuban Tourism During the 21st Century" (2015). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 194. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/194 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RACE AND INEQUALITY IN CUBAN TOURISM DURING THE 21 ST CENTURY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Social Sciences by Arah Marie Parker June 2015 RACE AND INEQUALITY IN CUBAN TOURISM DURING THE 21 ST CENTURY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Arah Marie Parker June 2015 Approved by: Dr. Teresa Velasquez, Committee Chair, Anthropology Dr. James Fenelon, Committee Member Dr. Cherstin Lyon, Committee Member © 2015 Arah Marie Parker ABSTRACT As the largest island in the Caribbean, Cuba boasts beautiful scenery, as well as a rich and diverse culture. -

Department of State

SI CUBA DEPARTMENT OF STATE CUBA DEPARTMENT OF STATE Contents I. The Betrayal of the Cuban Revolution . 2 Establishment of the Communist II.TheBridgehead 11 III. The Delivery of the Revolution to the Sino-Soviet Bloc 19 IV. The Assault on the Hemisphere ... 25 V.Conclusion 33 CUBA The present situation in Cuba confronts the Western Hemisphere and the inter-American sys¬ tem with a grave and urgent challenge. This challenge does not result from the fact chat the Castro government in Cuba was established by revolution. The hemisphere rejoiced at the over¬ throw of the Batista tyranny, looked with sympathy on the new regime, and welcomed its promises of political freedom and social justice for the Cuban people. The challenge results from the fact thar the leaders of the revolutionary regime betrayed their own revolution, delivered that revolution into the hands of powers alien to the hemisphere, and transformed it into an instrument employed with 1 calculated effect to suppress the rekindled hopes of the Cuban people for democracy and to intervene in the internal affairs of other American Republics. What began as a movement to enlarge Cuban democracy and freedom has been perverted, in short, into a mechanism for the destruction of free institutions in Cuba, for the seizure by international communism of a base and bridgehead in the Amer¬ icas, and for the disruption of the inter-American system. It is the considered judgment of the Government of the United States of America that the Castro regime in Cuba offers a clear and present danger to the authentic and autonomous revolution of the Americas—to the whole hope of spreading politi¬ cal liberty, economic development, and social prog¬ ress through all the republics of the hemisphere. -

Huber Matos Incansable Defensor De La Libertad En Cuba

Personajes Públicos Nº 003 Marzo de 2014 Huber Matos Incansable defensor de la libertad en Cuba. Este 27 de febrero murió en Miami, de un ataque al corazón, a los 95 años. , Huber Matos nació en 1928 en Yara, Cuba. guerra le valió entrar con Castro y Cienfue- El golpe de Estado de Fulgencio Batista (10 gos en La Habana, en la marcha de los vence- de marzo de 1952) lo sorprendió a sus veinti- dores (como se muestra en la imagen). cinco años, ejerciendo el papel de profesor en una escuela de Manzanillo. Años antes había conseguido un doctorado en Pedagogía por la Universidad de La Habana, lo cual no impidió, sin embargo, que se acoplara como paramili- tar a la lucha revolucionaria de Fidel Castro. Simpatizante activo del Partido Ortodoxo (de ideas nacionalistas y marxistas), se unió al Movimiento 26 de Julio (nacionalista y antiimperialista) para hacer frente a la dicta- dura de Fulgencio Batista, tras enterarse de la muerte de algunos de sus pupilos en la batalla De izquierda a derecha y en primer plano: de Alegría de Pío. El movimiento le pareció Camilo Cienfuegos, Fidel Castro y Huber Matos. atractivo, además, porque prometía volver a la legalidad y la democracia, y respetar la Una vez conquistado el país, recibió la Constitución de 1940. Arrestado por su comandancia del Ejército en Camagüey, pero oposición a Batista, escapó exitosamente a adoptó una posición discrepante de Fidel, a Costa Rica, país que perduró sentimental- quien atribuyó un planteamiento comunista, mente en su memoria por la acogida que le compartido por el Ché Guevara y Raúl dio como exiliado político. -

Huber Matos: His Life and Legacy (A Panel Discussion) Cuban Research Institute, Florida International University

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons Cuban Research Institute Events Cuban Research Institute 3-11-2014 Huber Matos: His Life and Legacy (A Panel Discussion) Cuban Research Institute, Florida International University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/cri_events Part of the Latin American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Cuban Research Institute, Florida International University, "Huber Matos: His Life and Legacy (A Panel Discussion)" (2014). Cuban Research Institute Events. 12. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/cri_events/12 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Cuban Research Institute at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cuban Research Institute Events by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Huber Matos: His Life and Legacy (A Panel Discussion) March 11,2014 | 2:00 PM Modesto A. Maidique Campus Greeen Library 220 Huber Matos Benftez (1918-2014) was a Cuban political activist and writer. Born in Yara (Oriente province), Cuba, he became a rural school teacher and rice farmer. In 1952, Matos opposed Fulgencio Batista's coup d'etat. In 1956, he joined Fidel Castro's guerrilla movement and became one of the leaders of the 26th of July Movement, which overthrew Batista's dictatorship. Matos grew increasingly critical of the movement's shift toward Marxism and closer ties with Communist leaders. He resigned his post as Military Governor of Camaguey in October 1959. Convicted of "treason and sedition" by the Castro regime, he spent 20 years in prison (1959-1979). Once in exile, Matos founded the anti-Castro organization Cuba lndependiente y Democratica (Independent and Democratic Cuba). -

Revista Hispano Cubana

revista 16 índice 6/10/03 12:14 Página 1 REVISTA HISPANO CUBANA Nº 16 Primavera-Verano 2003 Madrid Mayo-Septiembre 2003 revista 16 índice 6/10/03 12:14 Página 2 REVISTA HISPANO CUBANA HC DIRECTOR Javier Martínez-Corbalán REDACCIÓN Celia Ferrero Orlando Fondevila Begoña Martínez CONSEJO EDITORIAL Cristina Álvarez Barthe, Luis Arranz, Mª Elena Cruz Varela, Jorge Dávila, Manuel Díaz Martínez, Ángel Esteban del Campo, Alina Fernández, Mª Victoria Fernández-Ávila, Carlos Franqui, José Luis González Quirós, Mario Guillot, Guillermo Gortázar Jesús Huerta de Soto, Felipe Lázaro, Jacobo Machover, José Mª Marco, Julio San Francisco, Juan Morán, Eusebio Mujal-León, Fabio Murrieta, Mario Parajón, José Luis Prieto Benavent, Tania Quintero, Alberto Recarte, Raúl Rivero, Ángel Rodríguez Abad, José Antonio San Gil, José Sanmartín, Pío Serrano, Daniel Silva, Rafael Solano, Álvaro Vargas Llosa, Alejo Vidal-Quadras. Esta revista es Esta revista es miembro de ARCE miembro de la Asociación de Federación Revistas Culturales Iberoamericana de de España Revistas Culturales (FIRC) EDITA, F. H. C. C/ORFILA, 8, 1ºA - 28010 MADRID Tel: 91 319 63 13/319 70 48 Fax: 91 319 70 08 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.revistahc.com Suscripciones: España: 24 Euros al año. Otros países: 58 Euros al año, incluído correo aéreo. Precio ejemplar: España 8 Euros. Los artículos publicados en esta revista, expresan las opiniones y criterios de sus autores, sin que necesariamente sean atribuibles a la Revista Hispano Cubana HC. EDICIÓN Y MAQUETACIÓN, Visión Gráfica DISEÑO, -

Face to Face with Huber Matos

Face to Face With Huber Matos Theodore Jacqueney INTRODUCTION BY VICTORIA JACQUENEY Huber Matos, Cuba’s best-known polit- Costa ,Ria in a Costa Rian Govcrn- filled with the testimony of Cubans ical prisoner, was released on October ment plane, to be welcomed by his fam- who, like Huber Matos. had lost their 21. 1979, after completing “every min- ily and an immense crowd of prcss. wcll- initial enthusiasm for Castro’s revolu- ute” of a twenty-year prison sentence. wishers, and Costa Rican ollicials, in- tion as it became increasingly repressive Matos had helped make Fidel Castro’s cluding his old friend “Don Pepe” Fig- and had become victims of that reprcs- revolution, not only as a military com- ucres. sion themselves. mander in the rebel army, but by per- My husband, Ted Jacqueney, was On the day the Washington Post ran suading the then president of Costa there, at the invitation of the Matos Td’s first article about his trip, an Op- Ria, JosC Figuercs, to send arms to family. We had met one of the Matos Ed piece which concentrated on Huber Castro. When Matos asked to resign sons through a neighbor in Bli;r.ibeth, Matos, klubcr Matos Jr. .was seriously from Castro’s government because he New Jersey, just before Ted went to wounded near his home in Costa Rica disapproved of its increasingly Marxist Cuba in October, 1976. with a group of by gunmen who sprayed his car with direction, lie was charged with “slan- Ripon Society members who planned to machine-gun fire, escaping to Panama. -

Review of Julia E. Sweig's Inside the Cuban Revolution

Inside the Cuban Revolution: Fidel Castro and the Urban Underground. By Julia E. Sweig. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2002. xx, 255 pp. List of illustrations, acknowledgments, abbre- viations, about the research, notes, bibliography, index. $29.95 cloth.) Cuban studies, like former Soviet studies, is a bipolar field. This is partly because the Castro regime is a zealous guardian of its revolutionary image as it plays into current politics. As a result, the Cuban government carefully screens the writings and political ide- ology of all scholars allowed access to official documents. Julia Sweig arrived in Havana in 1995 with the right credentials. Her book preface expresses gratitude to various Cuban government officials and friends comprising a who's who of activists against the U.S. embargo on Cuba during the last three decades. This work, a revision of the author's Ph.D. dissertation, ana- lyzes the struggle of Fidel Castro's 26th of July Movement (M-26-7) against the Fulgencio Batista dictatorship from November 1956 to July 1958. Sweig recounts how the M-26-7 urban underground, which provided the recruits, weapons, and funds for the guerrillas in the mountains, initially had a leading role in decision making, until Castro imposed absolute control over the movement. The "heart and soul" of this book is based on nearly one thousand his- toric documents from the Cuban Council of State Archives, previ- ously unavailable to scholars. Yet, the author admits that there is "still-classified" material that she was unable to examine, despite her repeated requests, especially the correspondence between Fidel Castro and former president Carlos Prio, and the Celia Sánchez collection. -

CELIA and FIDEL the Cuban Revolution Profile: Fidel Castro Profile: Celia Sánchez Cuba-U.S

ARENA’S PAGE STUDY GUIDE THE PLAY Meet the Playwright Key Terms CELIA AND FIDEL The Cuban Revolution Profile: Fidel Castro Profile: Celia Sánchez Cuba-U.S. Relations Asylum-Seekers at the Peruvian Embassy and the Mariel Boatlift Three Big Questions Resources THE PLAY Fidel Castro, the political leader of Cuba and its revolution, is celebrating. Cuba’s support of the socialists in Angola (see article) is succeeding and, to him, it represents Cuba’s growing influence and power in the world. Celia Sánchez, his fellow revolutionary and most trusted political advisor, wants him to focus on his upcoming speech to the United Nations. She also urges him to face the realities in Cuba, where the people are clamoring for change and freedom. Fidel refuses. BY Consuelo, a spy and Fidel’s protégée, EDUARDO MACHADO arrives. She tells Fidel that Manolo, DIRECTED BY MOLLY SMITH a former revolutionary, is in Havana to meet with him. Manolo now works NOW PLAYING IN THE KOGOD CRADLE | FEBRUARY 28 - APRIL 12, 2020 for the U.S. government and is in Cuba on behalf of President Carter to discuss ending the trade embargo. “But, things are changing. People that grew up under our revolution are Their meeting is interrupted with unhappy. I think we have not given them enough things to dream and work for. startling news: hundreds of Cubans have stormed the Peruvian embassy They know about the world. And they want their own voice.” in Havana, asking the Peruvian — Celia Sánchez, Celia and Fidel government to help them leave Cuba. Will Fidel be able to cooperate with Celia, Manolo and Consuelo Celia and Fidel was generously commissioned by Drs. -

Reseña De" Cómo Llegó La Noche. Revolución Y Condena De Un

Revista Mexicana del Caribe ISSN: 1405-2962 [email protected] Universidad de Quintana Roo México Camacho Navarro, Enrique Reseña de "Cómo llegó la noche. Revolución y condena de un idealista cubano. Memorias" de Huber Matos Revista Mexicana del Caribe, vol. VII, núm. 14, 2002, pp. 217-224 Universidad de Quintana Roo Chetumal, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=12871407 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto RESEÑAS Huber Matos, Cómo llegó la noche. Revolución y condena de un idealista cubano. Memorias, prólogos de Hugh Thomas y Carlos Echeverría, Barce- lona, Tusquets (Tiempo de Memoria, 19), 2002. n marzo de 2003 tuve en mis manos un libro que se había E editado un año atrás. Se trataba del material que en el 2001 fue galardonado por el jurado del Premio Comillas de biografía, autobiografía y memorias. Jorge Semprún, en calidad de presi- dente, además de Miguel Ángel Aguilar, Ma. Teresa Castells, Jorge Edwards, Santos Juliá y Antonio López Lamadrid en representa- ción de Tusquets Editores, fueron los integrantes de dicho jurado. Desde su publicación se desarrolló una fuerte promoción en torno a ese texto y a su autor. En México se realizaron varias presen- taciones del autor e innumerables reseñas. Pese a que mi contacto con la obra fue tardío —es decir, sin estar al ritmo urgente de las modas académicas—, llevé a cabo mi lectura de Cómo llegó la noche. -

Presidential Brief: the Situation in Cuba

Resource Sheet #1 Presidential Brief: The Situation in Cuba Why was Cuba a concern for the United States in the 1950s? U.S. worries in the Caribbean and Central America, however, did not end with Arbenz. On the contrary, Cuba was an even bigger concern in the 1950s. Politically, Cuba had been fairly stable since Fulgencio Batista seized power from a reform-minded government in 1934. Washington supported Batista as a strongman who would maintain order on the island and not upset U.S. interests. Even after Batista’s defeat in elections in 1944, Cuba remained close to the United States. At the same time, though, official corruption and raft were mounting. Hope for reform suffered a setback when Batista staged a coup to take power in 1952. Few Cubans expected the Batista regime to tolerate democratic change in their country. As a result, resentment against the government grew during the 1950s. Few Americans were aware of Cuba’s political troubles. In the United States, Cuba was known best as a glamorous resort. A boom in tourism to the island began in the 1920s and reshaped Cuba’s image. Cuba was associated with casinos, nightclubs, and tropical beaches. American money helped provide Havana with more Cadillacs per capita than any city in the world during the 1950s. But the wealth also brought problems to Cuba. By the 1950s, American organized crime was firmly established on the island, along with drugs and prostitution. Economically, Cuba could claim one of the highest per capita incomes in Latin America. In reality, however, many Cubans could not find full-time employment, especially in the country side. -

Fidel Castro

History in the Making Volume 10 Article 10 January 2017 In Memoriam: Fidel Castro Andria Preciado CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making Part of the Latin American History Commons Recommended Citation Preciado, Andria (2017) "In Memoriam: Fidel Castro," History in the Making: Vol. 10 , Article 10. Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol10/iss1/10 This In Memoriam is brought to you for free and open access by the History at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in History in the Making by an authorized editor of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. In Memoriam In Memoriam: Fidel Castro By Andria Preciado “A revolution is a struggle to the death between the future and the past.” – Fidel Castro Fidel Castro died on November 25, 2016 at 90 years old in Havana, Cuba, after a dictatorship that lasted nearly five decades. Castro was a staple of the 20th century and an emblem of the Cold War. He was either loved or hated by those he encountered – national leaders and civilians alike – some were swayed by his charm and others fled from his brutal leadership. The Russians praised him; the Americans feared him; the world was perplexed by him; and his impact changed Cuba forever. Even after Castro’s death, people were still drawn to him; crowds mourned his passing in Havana, while others celebrated his death in the United States. The radically different reactions to his death across the globe stands as a testament to the revolutionary legacy he left behind.