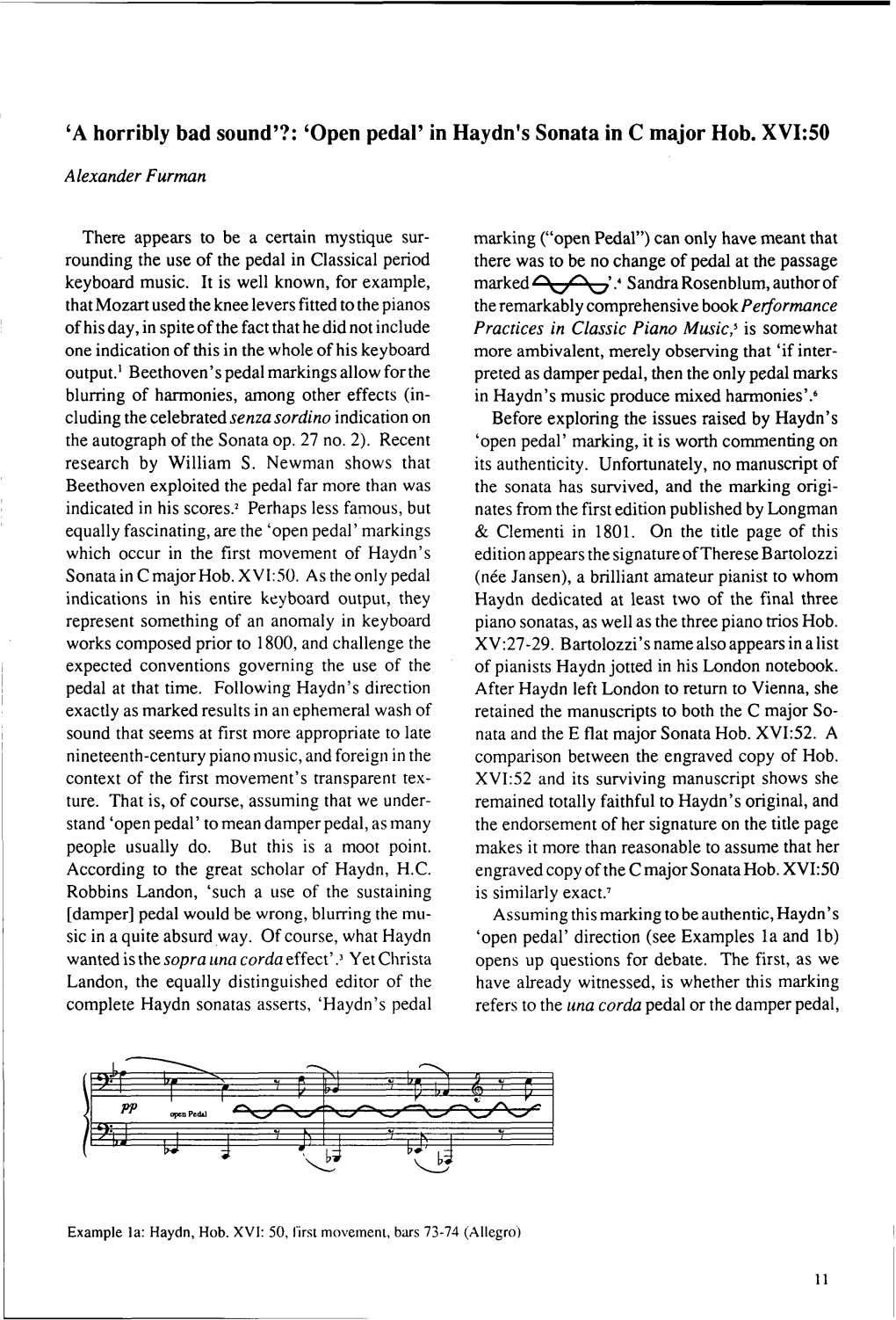

'A Horribly Bad Sound'?: 'Open Pedal' in Haydn's Sonata in C Major Hob

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Double Keyboard Concertos of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach

The double keyboard concertos of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Waterman, Muriel Moore, 1923- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 18:28:06 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318085 THE DOUBLE KEYBOARD CONCERTOS OF CARL PHILIPP EMANUEL BACH by Muriel Moore Waterman A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 7 0 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of re quirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judg ment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED: APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: JAMES R. -

NOVEMBER 2020 COMPLIMENTARY GUIDE Catskillregionguide.Com

Catskill Mountain Region NOVEMBER 2020 COMPLIMENTARY GUIDE catskillregionguide.com WELCOME HOME TO THE CATSKILL MOUNTAINS! With a Special Section: Visit Woodstock November 2020 • GUIDE 1 2 • www.catskillregionguide.com IN THIS ISSUE www.catskillregionguide.com VOLUME 35, NUMBER 11 November 2020 PUBLISHERS Peter Finn, Chairman, Catskill Mountain Foundation Sarah Finn, President, Catskill Mountain Foundation EDITORIAL DIRECTOR, CATSKILL MOUNTAIN FOUNDATION Sarah Taft ADVERTISING SALES Barbara Cobb Steve Friedman CONTRIBUTING WRITERS & ARTISTS Benedetta Barbaro, Darla Bjork, Rita Gentile, Liz Innvar, Joan Oldknow, Jeff Senterman, Sarah Taft, Margaret Donsbach Tomlinson & Robert Tomlinson ADMINISTRATION & FINANCE Candy McKee On the cover: The Ashokan Reservoir. Photo by Fran Driscoll, francisxdriscoll.com Justin McGowan & Emily Morse PRINTING Catskill Mountain Printing Services 4 A CATSKILLS WELCOME TO THE GRAF PIANO DISTRIBUTION By Joan Oldknow & Sarah Taft Catskill Mountain Foundation 12 ART & POETRY BY RITA GENTILE EDITORIAL DEADLINE FOR NEXT ISSUE: November 10 The Catskill Mountain Region Guide is published 12 times a year 13 TODAY BUILDS TOMORROW: by the Catskill Mountain Foundation, Inc., Main Street, PO Box How to Build the Future We Want: The Fear Factor 924, Hunter, NY 12442. If you have events or programs that you would like to have covered, please send them by e-mail to tafts@ By Robert Tomlinson catskillmtn.org. Please be sure to furnish a contact name and in- clude your address, telephone, fax, and e-mail information on all correspondence. For editorial and photo submission guidelines 14 VISIT WOODSTOCK send a request via e-mail to [email protected]. The liability of the publisher for any error for which it may be held legally responsible will not exceed the cost of space ordered WELCOME HOME TO THE CATSKILL MOUNTAINS! or occupied by the error. -

The Keyboad Sonatas of Domenico Scalatti and Eighteenth-Centuy Musical Style

THE KEYBOAD SONATAS OF DOMENICO SCALATTI AND EIGHTEENTH-CENTUY MUSICAL STYLE W. DEAN SUTCLIFFE St Catharine’sCollege, Cambridge published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB2 1RP, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Cambridge University Press 2003 Thisbook isin copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Bembo 11/13 pt. System LATEX2ε [TB] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0 521 48140 6 hardback CONTENTS Preface page vii 1 Scarlatti the Interesting Historical Figure 1 2 Panorama 26 Place and treatment in history 26 The dearth of hard facts29 Creative environment 32 Real-life personality 34 The panorama tradition 36 Analysis of sonatas 38 Improvisation 40 Pedagogy 41 Chronology 43 Organology 45 Style classification 49 Style sources 54 Influence 55 Nationalism I 57 Nationalism II 61 Evidence old and new 68 3 Heteroglossia 78 An open invitation to the ear: topic and genre 78 A love-hate relationship? -

Piano History

ABOUT THE PIANO A SHORT HISTORY OF THE PIANO If you have ever played a harpsichord or a clavichord, you know they feel dif- ferent from a piano. In a piano, a hammer is thrown at the strings when you press a key on the keyboard. The hammer quickly rebounds so the string can vi- brate for as long as you hold the key down (or even longer if you use the damper pedal). The harpsichord is different because the strings are plucked by a plectrum (originally the pointed end of a feather, now made of plastic or other synthetic material). Because the harpsichord plucks the string (as opposed to a hammer striking the string), you are very conscious of the moment the plucking takes place. The clavichord strikes the string with a metal tangent. Unlike the piano’s ham- mer that rebounds right away, the tangent stays in contact with the string. So the clavichord, too, has its own feel. A keyboard instrument called a virginal was a small and simple rectangular form of the harpsichord. The spinet was another small harpsichord-type instru- ment. These are some of the earliest keyboard instruments. Even the fortepiano, the name given to the earliest piano to distinguish it from the modern pianoforte, or piano, has its own feel—the depth of the key fall is shallow and it takes much less weight to press the key down. THE CRISTOFORI PIANOFORTE The piano itself was invented in Italy in 1709 by Bartolommeo Cristofori. His was a four-octave instrument (compared to our seven-and-a half-octave modern instrument), with hammers striking the strings just as they do on a modern pi- ano. -

Two-Piano Music of Franz Liszt Department of Music, University of Richmond

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Music Department Concert Programs Music 10-17-2011 Poetry and Passion: Two-Piano Music of Franz Liszt Department of Music, University of Richmond Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/all-music-programs Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Department of Music, University of Richmond, "Poetry and Passion: Two-Piano Music of Franz Liszt" (2011). Music Department Concert Programs. 9. http://scholarship.richmond.edu/all-music-programs/9 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Department Concert Programs by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 3 3082 01189 4473 r THE UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC Presents POETRY AND PASSION: TWO-PIANO MUSIC OF FRANZ LISZT Paul Hanson Joanne Kong pianists Monday, October 17, 2011 7:30p.m. Booker Hall of Music Camp Concert Hall FRANZ L!SZT POETRY AND PASSION: TWO-PIANO MUSIC OF FRANZ LISZT (1811-1886) Weihnachtsbaum (Christmas Tree) (1882) Psallite (Sing Psalms) Die Hirten an der Krippe (The Shepherds at the Manger) Adeste Fideles Gleichsam ais Marsch der heiligen drei Konige (In the manner of "The March of the Three Holy Kings") Scherzoso (Playful) Man zundet dle Kerzen des Baumes an (Lighting the candles on the tree) Carillon (Chimes) Schlummerlied (Slumber Song) Altes provenzalisches Weihnachtslied (Old Proven9al Christmas Song) Abendglocken (Evening Bells) Ehemals (Old Times) Polnisch (Polish) 9nfermfssfon Symphonic Poems, transcribed for two pianos by Liszt Festklange (Festive Sounds) (1853) Orphee (Orpheus) (1853-1854) Hunnenschlacht (Battle of the Huns) (1857) @Please silence cell phones, digital watches, and paging devices before the concert. -

EMV Announces 11 New Concerts for the Remainder of Its 51St Season

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE December 21, 2020 EMV Announces 11 New Concerts for the Remainder of its 51st Season Includes performances by Canadian icon Angela Hewitt, recorder virtuoso Vincent Lauzer, and returning EMV favourites Vancouver, BC – Early Music Vancouver (EMV) begins the second half of its 51st season on Wednesday January 13, 2021 at 7:30pm as part of its Digital Concert Hall. The virtual season will continue to be released on a bi-weekly basis, concluding on June 2, 2021. The 11 concerts feature a diverse range of programs, including J.S. Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto no. 5 performed by the Pacific Baroque Orchestra, West African music performed by Ensemble Constantinople and kora player Ablaye Cissoko, and a recital of 19th century lieder sung by Vancouver native Tyler Duncan accompanied by Erika Switzer on fortepiano. The first concert of the new year will be Vivaldi & Bach: The Trio Sonata in the 18th Century, performed by veterans of the early music movement, Marc Destrubé, former Music Director of the Pacific Baroque Orchestra and co- concertmaster of the Orchestra of the 18th Century, Jeanne Lamon, Tafelmusik Music Director Emerita, Christina Mahler, former principal cellist of Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra, as well as Christina Hutten, keyboardist of the Pacific Baroque Orchestra. Other notable concerts include New Music for Old Instruments in which the Pacific Baroque Orchestra performs newly commissioned pieces from BC-based composers in collaboration with Vancouver Pro Musica; Metamorfosi, showcasing music by Barbara Strozzi in the context of music from the Persian and Ottoman Empires performed by Ensemble Constantinople and incoming Artistic & Executive Director of EMV, Suzie LeBlanc; Angela Hewitt in recital performing J.S. -

Johann Sebastian Bach and the Fortepiano

Johann Sebastian Bach and the Fortepiano The keyboard music of J.S. Bach (Johann Sebastian Bach, 1685-1750 was mostly intended for the harpsichord. At that time, this instrument had a central position in the musical world, and had reached a state of high perfection. However, because it used a plucked string mechanism, it was not possible to express nuances on the keyboard, by playing loud or soft. The clavichord, on the other hand, another very popular instrument instrument, functioned by striking the strings, thus making different expressive nuances possible. Unfortunately, this instrument had a small range, and an extremely discreet sonority, which makes for a particularly confidential usage: it could hardly be used for public concerts. For that reason, the idea arose of replacing the plucked string system of the harpsichord with another, newly developed mechanism using hammers, which would strike the strings and thus make it possible to play with different dynamics. This was the system developed by Bartolomeo Cristofori (1655-1731), circa 1700 in Florence, Tuscany. Over the years, he developed and perfected his invention to a level of complexity which made his instruments expensive. Simplifications were made soon afterwards, only for the complex designs of Cristofori to reappear later in yet more highly developed pianos. This is a sure sign of his exceptional creativity. The simplified mechanism was introduced by Gottfried Silbermann (1683-1753), a well-known German organ builder, who had shown an interest in Cristofori’s new piano. During the mid-1730s, Silbermann had presented his simplified instrument to J.S. Bach, who was at that time not well pleased; he is said to have complained about the pinched sound in the high notes, and the heavy touch required. -

Classical Vienna 1

Classical Vienna Music for Guitar & Piano James Akers romantic guitar Gary Branch fortepiano RES10182 Ferdinando Carulli (1770-1841) Classical Vienna 1. Nocturne No. 1 [4:33] Music for Guitar & Piano Anton Diabelli (1781-1858) Sonata for the Piano Forte and Guitar, Op. 71 2. Allegro moderato [5:42] 3. Menuetto & Trio [4:48] James Akers romantic guitar 4. Polonaise [3:15] Ignaz Moscheles (1794-1870) Gary Branch fortepiano 5. Fantasia on ‘Potem Mitzwo!’ [6:12] Ferdinando Carulli 6. Nocturne No. 2 [3:45] Mauro Giuliani (1781-1829) Sonata Brillante, Op. 15 7. Allegro [6:06] 8. Adagio [4:59] Mauro Giuliani Variations on ‘Nel cor più non mi sento’ & Polonaise 9. Introduzione [1:57] 10. Variations [7:44] 11. Polonaise [9:14] About James Akers: Ferdinando Carulli ‘It’s a small soundscape, but when played with such beauty, 12. Variations on Themes taste and subtlety, an utterly enchanting one.’ by Rossini [9:24] BBC Music Magazine Total playing time [67:47] Classical Vienna: Music for Guitar resounded to more comforting sounds. Music and Fortepiano publishers poured out vast quantities of works written by skilled craftsmen composers intent By the early-nineteenth century, long term on quieting, not arousing, the latent and societal changes in Europe had created a unseemly passions of the European elite. prosperous and expanding middle class. The values and culture of this group, mainly The market for music lessons, sheet music concerned with aspiration and self- and performances provided gainful improvement, quickly became established, employment for the composers featured on and remained reasonably consistent this recording, many of whom were able to thereafter. -

Performance Practice and the Classic Period Malcom S

Performance Practice Review Volume 1 Article 4 Number 1 Spring/Fall 'Back to the Land': Performance Practice and the Classic Period Malcom S. Cole Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Musicology Commons, Music Performance Commons, and the Music Practice Commons Cole, Malcom S. (1988) "'Back to the Land': Performance Practice and the Classic Period," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 1: No. 1, Article 4. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.198801.01.4 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol1/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'Back to the Land': Performance Practice and the Classic Period1 Malcolm S. Cole Interest in performance practice (performing practice, historical performance) is a 20th-century phenomenon. Digging through the accretions of centuries, performer-scholars in ever-growing numbers are striving to recover "authentic" styles, to go "back to the land," in Adam Carse's delightful phrase. For the Classic period specifically, no longer does the misconception prevail that performance problems declined dramatically (or vanished) as notation and instruments became more like today's. To the contrary, numerous issues invite attention. First, however, I recommend reflection in three broad areas: the peculiarly elusive nature of the subject; the ground covered by the term "Classic period"; the apparent continuity of performing tradition from 1. The following abbreviations are used in this paper AM: Acta musicologica; JAMS: Journal of the American Musicological Society; JM: Journal of Musicoiogy; MJb: Mozart Jahibuch; ML: Music and Letters; MT. -

Domenico Scarlatti

Nimbus DOMENICO Nimbus 5 CDs SCARLATTI DOMENICO SCARLATTI • THE COMPLETE SONATAS • DOMENICO SCARLATTI VOLUME V THE COMPLETE SONATAS • DOMENICO SCARLATTI Venice XII – XIII (1756-7) (K484 – 543) Continuo Sonatas (K78, K81, K88 – 91) Richard Lester Harpsichord & Fortepiano Academia Musicali NI 1729 NI 1729 DOMENICO SCARLATTI 5 CD set The Complete Sonatas DOMENICO other titles in this series SCARLATTI Volumes I • II • III • IV • VI • VII VOLUME V DOMENICO DOMENICO DOMENICO SCARLATTI SCARLATTI SCARLATTI Venice XII – XIII (1756-7) VOLUME I VOLUME II VOLUME III (K484 – 543) Essercizi per Gravicembalo Venice III – V (1753) Venice VI – VIII (1753-4) (K1-30) (K206 – 295) (K296 – 355, K358 – 387) Venice I & II (1752) (K49, K98, K99, K129, K148-201) Continuo Sonatas RICHARD LESTER RICHARD LESTER Harpsichord RICHARD LESTER Harpsichord & Organ Harpsichord & organ (K78, K81, K88 – 91) Richard Lester DOMENICO DOMENICO DOMENICO SCARLATTI SCARLATTI SCARLATTI Harpsichord & Fortepiano VOLUME IV VOLUME VI VOLUME VII Venice IX – XI (1754-6) Appendices & Diversities Academia Musicali Venice XIV (1742) (K388 – 451, K454 – 483) 57 Sonatas (K3, 10-12, 17, 31, 36-38, 43-77, 79, 80, 82-87, 92, 93) RICHARD LESTER Venice XV (1749) RICHARD LESTER (K96, K98-138) Harpsichord Harpsichord & FORTEPIANO RICHARD LESTER Harpsichord For availability and complete track details please visit www.wyastone.co.uk/nrl/scarlatti.html NI 1729 DOMENICO SCARLATTI Richard Lester Scarlatti’s sonatas. He subsequently recorded an album of Scarlatti sonatas which was hailed by all the The Complete Sonatas Through this single recorded marathon Richard major recording magazines as ‘brilliant’. He has Lester has now established an international reputation written extensively for music magazines and as a virtuoso harpsichordist. -

BEETHOVEN World.Citizen.Music 17 December 2019 to 26 April 2020

BEETHOVEN World.Citizen.Music 17 December 2019 to 26 April 2020 Media Conference: Friday, 13 December 2019, 11.30 a.m. Content 1. General Information Page 2 2. Media Information Page 4 3. Chapters in the Exhibition Page 5 4. Publication Page 10 5. Guided Tours and Events Page 11 Press Officer Sven Bergmann T +49 228 9171-205 F +49 228 9171-211 [email protected] General Information Exhibition 17 December 2019 to 26 April 2020 Managing Director Patrick Schmeing Curator s Agnieszka Lulięska Julia Ronge Press Officer Sven Bergmann Catalogue / Press Copy €35/ 17 Opening Hours Tuesday and Wednesday: 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. Thursday to Sunday: 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. Public Holidays: 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. Closed on Mondays 24 December closed 25 and 26 December 2019 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. 31 December 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. 1 January 2020 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. Admission €14/ €9 (incl. mediaguide) standard / reduced combined ticket, €20/ €13 Bundeskunsthalle and Beethoven-Haus Bonn standard / reduced Free admission for all under 19s and for refugees Happy Hour-Ticket € 7 Tuesday and Wednesday: 7 to 9 p.m. Thursday to Sunday: 5 to 7 p.m. (for individuals only) Public Transport Underground lines 16, 63, 66 and bus lines 610, 611 and 630 to Heussallee / Museumsmeile Deutsche Bahn / UN-Campus: Lines RE 5 (Rhein-Express), RB 26 (MittelrheinBahn), RB 30 (Rhein-Ahr-Bahn) and RB 48 (Rhein-Wupper-Bahn) Parking There is a car and coach park on Emil-Nolde- Straße behind the Bundeskunsthalle. -

MAKER: Interdisciplinary Senior Design Project to Print Mozart's

Paper ID #15574 MAKER: Interdisciplinary Senior Design Project to Print Mozart’s Fortepi- ano Dr. Yalcin Ertekin, Drexel University (Tech.) Dr. Ertekin received his BS degree in mechanical engineering from Istanbul Technical University. He received MS degree in Production Management from Istanbul University. After working for Chrysler Truck Manufacturing Company in Turkey as a project engineer, he received dual MS degrees in engi- neering management and mechanical engineering from Missouri University of Science and Technology (MS&T), formerly the University of Missouri-Rolla. He worked for Toyota Motor Corporation as a qual- ity assurance engineer for two years and lived in Toyota City, Japan. He received his Ph.D. in mechanical engineering from MS&T in 1999 while he worked as a quality engineer for Lumbee Enterprises in St. Louis, Missouri. His first teaching position was at the architectural and manufacturing Sciences depart- ment of Western Kentucky University. He was a faculty at Trine University teaching mainly graduate courses as well as undergraduate courses in engineering technology and mechanical engineering depart- ments. He is currently teaching in Engineering Technology Program at Drexel University. His area of expertise is in CAD/CAM, Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machining, rapid prototyping and qual- ity control. His research interest includes sensor based condition monitoring of CNC machining, machine tool accuracy characterization and enhancement, non-invasive surgical tool design, reverse engineering and bio materials. Dr. Warren Rosen, Drexel University (Eng. & Eng. Tech.) Dr. Warren Rosen received his Ph.D. in physics from Temple University. He has served as Assistant Professor of Physics at Colby and Vassar Colleges where he carried out research in solar physics, medical physics, and instrumentation.