National Fishery Sector Overview Samoa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FAO Fisheries & Aquaculture

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Fisheries and for a world without hunger Aquaculture Department Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles The Independent State of Samoa Part I Overview and main indicators 1. Country brief 2. General geographic and economic indicators 3. FAO Fisheries statistics Part II Narrative (2017) 4. Production sector Marine sub-sector Inland sub-sector Aquaculture sub-sector Recreational sub-sector Source of information United Nations Geospatial Information Section http://www.un.org/Depts/Cartographic/english/htmain.htm 5. Post-harvest sector Imagery for continents and oceans reproduced from GEBCO, www.gebco.net Fish utilization Fish markets 6. Socio-economic contribution of the fishery sector Role of fisheries in the national economy Trade Food security Employment Rural development 7. Trends, issues and development Constraints and opportunities Government and non-government sector policies and development strategies Research, education and training Foreign aid 8. Institutional framework 9. Legal framework Regional and international legal framework 10. Annexes 11. References Additional information 12. FAO Thematic data bases 13. Publications 14. Meetings & News archive FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department Part I Overview and main indicators Part I of the Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profile is compiled using the most up-to-date information available from the FAO Country briefs and Statistics programmes at the time of publication. The Country Brief and the FAO Fisheries Statistics provided in Part I may, however, have been prepared at different times, which would explain any inconsistencies. Country brief Prepared: May, 2018 Samoa has a population of 195 000 (2016), a land area of 2 935 km2, a coastline of 447 km, and an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of 129 000 km2. -

SAMOA Aquaculture Management and Development Plan 2013–2018

SAMOA Aquaculture Management and Development Plan 2013–2018 Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries SAMOA Aquaculture Management and Development Plan 2013–2018 Aquaculture Section Fisheries, Aquaculture and Marine Ecosystems Division Secretariat of the Pacific Community © Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC) 2012 All rights for commercial / for profit reproduction or translation, in any form, reserved. SPC authorises the partial reproduction or translation of this material for scientific, educational or research purposes, provided that SPC and the source document are properly acknowledged. Permission to reproduce the document and/or translate in whole, in any form, whether for commercial / for profit or non-profit purposes, must be requested in writing. Original SPC artwork may not be altered or separately published without permission. Original text: English Secretariat of the Pacific Community Cataloguing-in-publication data Samoa aquaculture management and development plan / Secretariat of the Pacific Community Aquaculture Section 1. Aquaculture — management — Samoa. 2. Aquaculture – Economic aspects — Samoa. 3. Aquaculture – Law and legislation — Samoa. I. Title. II. Secretariat of the Pacific Community. 639.8099614 AACR2 ISBN: 978-982-00-0598-3 Secretariat of the Pacific Community BP D5, 98848 Noumea Cedex, New Caledonia Tel: +687 26.20.00 Fax: +687 26.38.18 www.spc.int [email protected] Prepared for publication at SPC headquarters, Noumea, New Caledonia, 2012 Printed at SPC, Noumea, New Caledonia, 2012 CONTENTS Foreword 1. Vision and goal for aquaculture in Samoa 1 2. General introduction 1 2.1. Current status of the aquaculture sector 2.2. Legal and policy framework 3. Strategies 2 4. Action plan 4 4.1. -

Lessons from Past and Current Aquaculture Inititives in Selected

SUB-REGIONAL OFFICE FOR THE PACIFIC ISLANDS TCP/RAS/3301 LESSONS FROM PAST AND CURRENT AQUACULTURE INITIATIVES IN SELECTED PACIFIC ISLAND COUNTRIES Prepared by Pedro B. Bueno FAO Consultant ii Lessons learned from Pacific Islands Countries The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. © FAO, 2014 FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www. fao.org/contact-us/licence-request or addressed to [email protected]. -

FISHERY COUNTRY PROFILE Food and Agriculture Organization of The

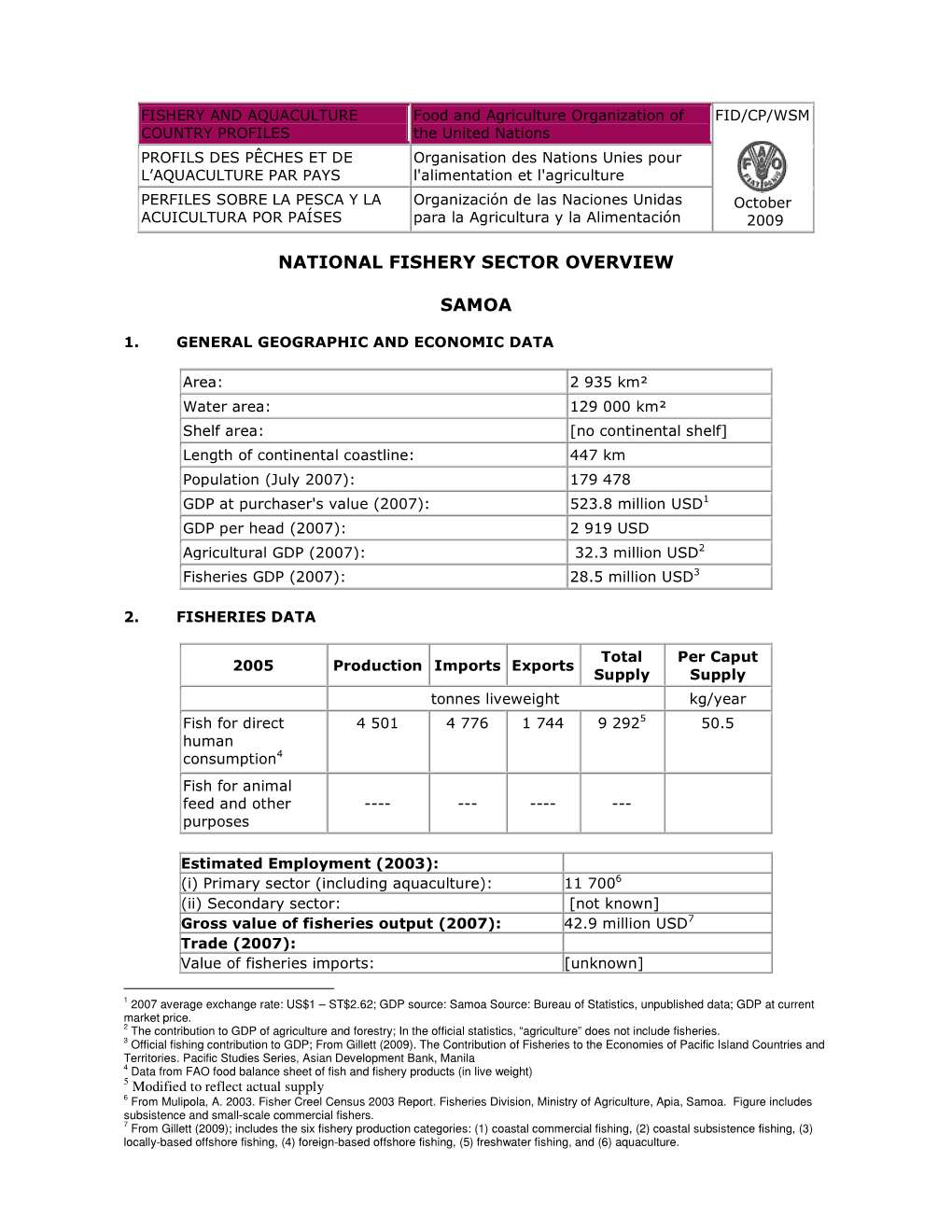

FISHERY Food and Agriculture FID/CP/SAM COUNTRY Organization of the United Rev.3 PROFILE Nations PROFIL DE LA Organisation des Nations PÊCHE PAR PAYS Unies pour l'alimentation April 2002 et l'agriculture RESUMEN Organización de las INFORMATIVO Naciones Unidas para la SOBRE Agricultura y la LA PESCA POR Alimentación PAISES SAMOA GENERAL ECONOMIC DATA1 Land area2: 2,935 sq. km Shelf area (to 200m): 4,500 sq. km Ocean area: 120,000 sq. km Length of coastline: 447 km Population (1999)3: 168,000 Gross Domestic Product US$ 230.1 million (1999)4: Fishing contribution to GDP US$ 15.3 million (1999): GDP per caput (1999): US$ 1,370 FISHERIES DATA Commodity balance (1999): Produc- Imports Exports Total Per tion supply caput supply Tonnes liveweight equivalent kg/yr Fish for 12,535 2,450 4,657 10,328 61.5 direct human consumption5 Fish for 0 0 0 0 animal feed and other purposes Estimated employment (1999): (i) Primary sector: 900 STRUCTURE AND CHARACTERISTICS OF THE INDUSTRY General Samoa consists of two main islands, Upolu and Savaii, seven smaller islands (two of which are inhabited), and several islets and rock outcrops. The total land area is 2,935 sq. km. The 1999 population of about 168,000 reside in 326 villages, of which 68% are on the island of Upolu. About 230 villages are considered to be coastal villages. Barrier reefs enclosing narrow lagoons encircle much of the coastline except for the north coast of Upolu, the main island, where there is an extensive shelf area which extends up to 14 miles offshore. -

TAHITI AQUACULTURE 2010 Book of Abstracts Livre Des Résumés

TTAAHHIITTII AAQQUUAACCUULLTTUURREE 22001100 BBooookk ooff aabbssttrraaccttss LLiivvrree ddeess rrééssuummééss SUMMARY Opening presentation 4 National and regional presentations (part 1) 6 National and regional presentations (part 2) 21 Experts presentations: Challenges in island aquaculture 37 Aquatic animal health management in tropical island environment 46 Hatchery based aquaculture (1) : shrimp farming 55 SPC shrimp working group 61 Hatchery based aquaculture (2): fish farming 63 Hatchery based aquaculture (3) 71 Capture based aquaculture 81 Governance of aquaculture in tropical islands environment 86 Aquaculture’s social and economic development and interactions 90 with fisheries on tropical islands Poster Session 97 - 2 - SOMMAIRE 4 Discours d'ouverture 6 Présentations nationales / régionales (1ère partie) 21 Présentations nationales / régionales (2ème partie) 37 Les enjeux : présentations d'experts 46 Environnement et santé aquacole en milieu insulaire tropical 55 Aquaculture basée sur l'écloserie (1) : Crevetticulture 61 Groupe de travail Crevettes CPS 63 Aquaculture basée sur l'écloserie (2) : pisciculture 71 Aquaculture basée sur l'écloserie (3) 81 Aquaculture basée sur le prélèvement durable dans le milieu naturel 86 Gouvernance de l'aquaculture en milieu insulaire tropical Développement économique et social et interactions avec la pêche 90 en milieu insulaire tropical 97 Session Poster - 3 - English Opening presentation Chair : Dr. J. JIA Monday 6/12 Facilitator : M. L. DEVEMY 10.10 - 12.20 am Chief of aquaculture service (FIRA), FAO Dr. Jiansan JIA Global Aquaculture Development - Present Status,Trends and Challenges for Future Growth Français Discours d'ouverture Président : Dr. J. JIA Lundi 6/12 Modérateur : M. L. DEVEMY 10.10 - 12.20 am Chef, service Aquaculture (FIRA), FAO Dr. -

Ocean Governance in Samoa: a Case Study of Ocean Governance in the South Pacific

OCEAN GOVERNANCE IN SAMOA: A CASE STUDY OF OCEAN GOVERNANCE IN THE SOUTH PACIFIC Anama Solofa DIVISION FOR OCEAN AFFAIRS AND THE LAW OF THE SEA OFFICE OF LEGAL AFFAIRS, THE UNITED NATIONS NEW YORK, 2009 The United Nations-Nippon Foundation Fellowship Programme 2009 - 2010 DISCLAIMER The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of Samoa, the United Nations, the Nippon Foundation of Japan, or the University of Delaware. © 2009 Anama Solofa. All rights reserved. ii SUPERVISORS: Prof. Biliana Cicin-Sain Dr. François Bailet iii Acknowledgements This research paper would not have been possible had I not had the support, assistance, and encouragement of so many people. My sincerest gratitude goes to the Nippon Foundation of Japan and the United Nations’ Division of Ocean Affairs and Law of the Sea (UN-DOALOS) for their continued support of the Fellowship Programme. This research would not have been possible without the Fellowship award that was granted to me. I would like thank Dr. Biliana Cicin-Sain, my supervisor during the first phase of the Fellowship with the Gerard J Mangone Center for Marine Policy of the University of Delaware, for showing me the ropes and allowing me to learn from her wealth of experience in the field of marine policy. The staff, students and volunteers at the Center were supportive and encouraging as I waded into the realm of ocean policy and governance. A special thank you to Dr. Miriam Balgos for her patience, understanding, assistance, and tolerance of all my questions. -

Impact Assessment of Investment in Aquaculture-Based Livelihoods in the Pacific Islands Region and Tropical Australia

Impact assessment of investment in aquaculture-based livelihoods in the Pacific islands region and tropical Australia ACIAR Impact Assessment Series 96 Impact assessment of investment in aquaculture-based livelihoods in the Pacific islands region and tropical Australia Mr Michael Clarke AgEconPlus Pty Ltd Dr Katja Mikhailovich KPM Epoch Consulting ACIAR Impact Assessment Series Report No. 96 Research that works for developing countries and Australia The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) was established in June 1982 by an Act of the Australian Parliament. ACIAR operates as part of Australia’s international development cooperation program, with a mission to achieve more productive and sustainable agricultural systems, for the benefit of developing countries and Australia. It commissions collaborative research between Australian and developing‑country researchers in areas where Australia has special research competence. It also administers Australia’s contribution to the International Agricultural Research Centres. Where trade names are used, this constitutes neither endorsement of nor discrimination against any product by ACIAR. ACIAR IMPACT ASSESSMENT SERIES ACIAR seeks to ensure that the outputs of the research it funds are adopted by farmers, policymakers, quarantine officers and other beneficiaries. In order to monitor the effects of its projects, ACIAR commissions independent assessments of selected projects. This series of publications reports the results of these independent studies. Numbers in this series are distributed internationally to selected individuals and scientific institutions, and are also available from ACIAR’s website at aciar.gov.au. © Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) 2018 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from ACIAR, GPO Box 1571, Canberra ACT 2601, Australia, [email protected]. -

Fisheries in the Economies of the Pacific Island Countries and Territories

Fisheries in the Economies Pacific Studies Series About Fisheries in the Economies of the Pacific Island Countries and Territories The fishing industry benefits the people and economies of the Pacific in various ways but the full value of these benefits is not reflected in the region’s statistics. Records may be maintained but they are not complete, or accurate, or comparable. The research summarized in this report reaffirms the importance of this sector to the economies and societies of the Pacific island countries. The research reveals that the full value of fisheries is likely to have eluded statisticians, and therefore fisheries authorities, government decision makers, and donors. But its value has never escaped the fisher, fish trader, and fish processor. The difference in appreciation between public and private individuals must raise the question of whether fisheries are receiving adequate attention from the public sector—including the necessary management and protection, appropriate research, development, extension and training, and sufficient investment. About the Asian Development Bank of the Pacific Island Countries and Territories of the Pacific ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacific region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries substantially reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to two-thirds of the world’s poor: 1.8 billion people who live on less than $2 a day, with 903 Fisheries in the Economies million struggling on less than $1.25 a day. ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally of the Pacific Island Countries sustainable growth, and regional integration. -

Fisheries of the Pacific Islands: Regional and National Information

RAP PUBLICATION 2011/03 Fisheries of the Pacific Islands Regional and national information vi RAP PUBLICATION 2011/03 Fisheries of the Pacific Islands Regional and national information Robert Gillett FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS REGIONAL OFFICE FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC BANGKOK, 2011 i The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-106792-5 All rights reserved. FAO encourages reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Non-commercial uses will be authorized free of charge, upon request. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes, including educational purposes, may incur fees. Applications for permission to reproduce or disseminate FAO copyright materials, and all other queries concerning rights and licences, should be addressed by e-mail to [email protected] or to the Chief, Publishing Policy and Support Branch, Office of Knowledge Exchange, Research and Extension, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy. -

Fish, Fishing and Community in North Korea and Neighbours Vibrant Matter(S) Fish, Fishing and Community in North Korea and Neighbours

Robert Winstanley-Chesters Fish, Fishing and Community in North Korea and Neighbours Vibrant Matter(s) Fish, Fishing and Community in North Korea and Neighbours Robert Winstanley-Chesters Fish, Fishing and Community in North Korea and Neighbours Vibrant Matter(s) Robert Winstanley-Chesters University of Leeds Leeds, West Yorkshire, UK ISBN 978-981-15-0041-1 ISBN 978-981-15-0042-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-0042-8 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adap- tation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publi- cation does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

SPC Fisheries Newsletter #158 - January–April 2019 • SPC Activities •

FisheriesNewsletter #158 January–April 2019 In this issue Editorial SPC activities Two of the three feature articles in this issue relate to coastal marine resource P 2 Scaling up Tonga special management areas through community- assessments, and they, not surprisingly, ring alarm bells. to-community exchange In Fiji, Jeremy Prince and colleagues assessed the spawning potential of 29 ISSN: 0248-076X P 7 Electronic reporting logsheet systems: Beauty and the beast reef fish species using a new technique called the length-based spawning P 8 PROTEGE takes off potential ratio (p. 28). The methodology involves community members P 10 Strengthening small aquaculture businesses through improved who are trained to measure fish length and assess fish maturity stages. The financial literacy training gives them a glimpse of the science ‘hiding’ behind management decisions. With a better understanding of why stocks need to be managed, News from in and around the region community members should better accept regulations when these are put in P 12 Golden sandfish farming in Tonga – initial trials underway place. And, regulations will be needed, as the researchers’ findings show that P 14 Mozuku farming in Tonga: Treasure under the sea! many of the stocks studied are in crisis. P 16 2018 Market price update for beche-de-mer in Melanesian countries In Pohnpei, Federated States of Micronesia, Andrew Halford, Pauline P 21 Scientists collect the world’s deepest mesophotic coral: A hope for Bosserelle and their research team have collected data on mangrove crab rescuing shallow-water corals stocks (p. 42). They found a resource clearly in need of a new management P 24 Mainstreaming gender into fisheries and aquaculture in Samoa plan but note that the real challenge will be its effective implementation. -

Study on the Potential of Aquaculture in the Pacific

Study on the Potential of Aquaculture in the Pacific To the ACP-EU Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Co-operation (CTA) Prepared by Moses Amos, Ruth Garcia, Tim Pickering & Robert Jimmy Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC), Noumea August, 2014 Table of Contents Acronyms .......................................................................................................................................... 3 1 Summary ................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Preparation of this document ............................................................................................. 4 1.2 General Conclusions ........................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Key aspirations and attributes for Pacific Aquaculture ........................................................ 5 1.3.1 Aspirations ................................................................................................................. 5 1.3.2 Attributes ................................................................................................................... 5 1.4 Contribution to food and nutrition security ........................................................................ 5 1.5 Contribution to improving livelihoods ................................................................................ 5 1.6 Addressing long-term sustainability of the aquaculture sector ..........................................