Chapter 1–Budget Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enhanced Tax-Exempt Yield

June 2021 Enhanced Tax-Exempt Yield ® HYD VanEck Vectors® High Yield Muni ETF Would your portfolio benefit from tax-free income? Why HYD? High yield municipal bonds amplify two of the key features of the municipal bond asset class, Attractive Tax-Advantaged Income tax-exempt income and low default rates. For investors with taxable investment accounts, Underlying Index comprised of highest-yielding municipal bonds provide a source of tax-free compounding of returns. High-yield municipal municipal bonds with income generally exempt bonds provide an enhanced income potential due to their lower relative credit rating. from federal taxes. Enhanced Liquidity Index includes 25% BBB investment-grade Attractive Total Return Risk/Reward Profile1 exposure for enchanced liquidity. 6/30/2016 - 6/30/2021 Diverse Sector Exposure and Low Default Rates TAXABLE EQUIVALENT 12 (Federal Tax Rates) Index covers wide range of muni sectors and securities with historically low default rates.2 37% 35% 32% 10 24% VanEck’s Municipal Income Suite 8 High Yield Corps Yield Curve Positioning SMB | Short Muni ETF High Yield Muni 6 ITM | Intermediate Muni ETF MBS Corps MLN | Long Muni ETF Muni Credit Quality Focused 4 U.S. Aggregate Annualized Return (%) SHYD | Short High Yield Muni ETF Global Gov Agency U.S. Gov HYD | High Yield Muni ETF 2 Smart Beta XMPT | CEF Municipal Income ETF 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Tactical Risk (Annualized Standard Deviation) MAAX | Muni Allocation ETF Source: FactSet. All data based on indices. See reverse for index descriptions. 2Source: Moody’s Investors Services; “U.S. Municipal Bond High-yield municipal bonds have provided higher risk-adjusted returns and have experienced Defaults and Recoveries, 1970-2020” lower overall default rates when compared with other taxable and tax-exempt bonds. -

Forfeiting Federalism: the Faustian Pact with Big Tobacco

FORFEITING FEDERALISM: THE FAUSTIAN PACT WITH BIG TOBACCO Ryan D. Dreveskracht* 291 Ryan Dreveskracht is an Associate at Galanda Broadman, PLLC. His practice focuses on representing tribal governments in public affairs, energy, gaming, taxation, and general economic development. He can be reached at 206.909.3842 or [email protected]. The Author would like to thank Dale White, Lane Morgan, and John Peebles for their thoughtful comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of this work. Any mistakes are my own. 292 RICHMOND JOURNAL OF LAW AND THE PUBLIC INTEREST [Vol. XVIII:iii INTRODUCTION "Certainly many of us never anticipated that states would become addicted to the tobacco money as a way to finance their operations." 1 - Scott Harshbarger, Attorney General, State of Massachusetts This article discusses the effects of the largest legal settlement in United States history: the so-called Master Settlement Agreement2 , or "MSA." Part I discusses the settlement generally, and its intended effect on the U.S. tobacco market. Parts II through IV discuss the unintended consequences of the settlement.' Part II considers how states got into their current disar- ray, and how a perceived state windfall of billions of dollars ended up put- ting states on what by all accounts now appears to be very real risk of insol- vency. Part III examines how the major tobacco companies are using the states' dire financial condition to stifle tribal sovereignty and Indian indus- try. Part IV analyzes the federal government's role in similar oppressive tactics. The concluding section suggests lessons that might be learned from the MSA. -

Overview of the Lehman Brothers Municipal Product Group

Confidential Presentation to: Lehman Brothers Overview of the Lehman Brothers Municipal Product Group July 26, 2007 Table of Contents Section Header (used to create Tab Pages and Table of Contents) I. The Basics of Municipal Bonds II. New Issues & Secondary Trading III. Short Term Municipal Products Group IV. Municipal High Yield V. Municipal Structured Products and Derivatives VI. Municipal Relative Value VII. Municipal Bond Index VIII. The Lehman Advantage IV. Municipal Contacts 1 I. The Basics of Municipal Bonds Municipal Asset Class ! Asset Preservation – Municipal assets are widely considered the safest fixed- income asset class, save Treasuries, boasting a 10-year cumulative default rate of 0.1032% since 1970, versus 9.70% for corporate bonds (Moody’s). Approximately 70% of the market is AAA rated. ! Income Stream – Municipal securities range in maturity from daily floaters to bonds maturing out 40 years and longer. Portfolios can be constructed to provide specific tax-exempt cash flows. ! Tax Advantage – Investors often under appreciate the value of tax savings. During 2006, long AAA municipal securities traded between 85% - 95% of the 30-year U.S. Treasury. Consequently, investors in the highest tax bracket could have earned as much as 145% of Treasuries on a tax adjusted basis. ! Lower Volatility – Tax-exempt yield movements lag the Treasury market. Muted municipal yield movements result in stability of investment capital. ! Correlation – Municipal risk is typically less correlated to the core risk in taxable investment portfolios. 2 Tax Status of Fixed Income Assets ! The interest received on all municipal securities is exempt from the Federal income tax. Investors who purchases municipal securities indigenous to their state of residence are often exempt from state and local taxes as well (although a few states do tax in-state municipal bonds). -

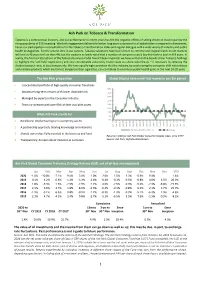

Ash Park on Tobacco & Transformation

Ash Park on Tobacco & Transformation Tobacco is a controversial industry, and our performance in recent years has felt the negative effects of selling driven at least in part by the rising popularity of ESG investing. We think engagement delivers far better long-term outcomes for all stakeholders compared to divestment, hence our participation in consultations for the Tobacco Transformation Index and regular dialogue with a wide variety of industry and public health protagonists. For the second time in our careers, Tobacco valuations have been driven to extreme and illogical levels: credit markets will lend at 40 years for less than 4%, but the equity is so lowly-rated that a number of companies could buy themselves back in 8-9 years. In reality, the financial attractions of the Tobacco business model haven’t been impaired; we have written to the boards of our Tobacco holdings to highlight the ‘self-help’ opportunity and very considerable value they could create via share repurchases – if necessary by rebasing the dividend payout ratio, at least temporarily. We have equally high conviction that the industry, by accelerating the consumer shift into tobacco and nicotine products which are far less dangerous than cigarettes, can contribute to enormous public health gains in the next 10-20 years. The Ash Park proposition Global Staples have never lost money in any 5yr period • Concentrated portfolio of high-quality consumer franchises 40% • Attractive long-term returns with lower downside risk 35% 30% • Managed by experts in the Consumer industry 25% • Team co-invested with over 90% of their available assets 20% 15% 10% What Ash Park stands for 5% 1. -

State Legislated Actions on Tobacco Issues: 2007 Improving Life, One Breath at a Time 1-800-LUNGUSA

T OBACCO P OLICY P ROJECT State Legislated Actions on Tobacco Issues: 2007 www.lungusa.org Improving Life, One Breath at a Time 1-800-LUNGUSA Foreword 2007 Passed Legislation– State Pages Summarizes major accomplish- by Issue Provides summaries of ments in state tobacco control Outlines relevant tobacco tobacco control laws with policy during 2007. control legislation passed in code/statute citations in each state and the District of effect in each state and the SLATI Overview Columbia in 2007 by issue. District of Columbia as of Gives a synopsis of current January 1, 2008. tobacco control laws in all 2007 Passed Legislation– 50 states and the District of by State Appendices Columbia as of January 1, Lists relevant tobacco control leg- Condenses certain information 2008 of each category islation passed in each state and presented in SLATI into nine tracked in SLATI. the District of Columbia in 2007. charts and maps. Acknowledgments State Legislated Actions On Tobacco Issues (SLATI), 19th Edition, 2007, was researched and written by the American Lung Association Government Relations Office. Thomas Carr, Manager, National Policy, wrote and edited the report. Josephine Ceselski, Manager, National Advocacy; Erika Sward, Director, National Advocacy; and Paul Billings, Vice President, National Policy and Advocacy helped review the report. Jean Haldorsen, Assistant Director, Production, assisted in the production of the report. American Lung Association field offices and their staff provided valuable information for and review of the report. Many others patiently answered requests for documents and information. The American Lung Association assumes sole responsibility for the content of the 19th edition of SLATI. -

Michael L. Fitzgerald, Treasurer of State REQUEST FOR

Michael L. Fitzgerald, Treasurer of State REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS LEAD MANAGING AND CO-MANAGER UNDERWRITERS TOBACCO SETTLEMENT ASSET-BACKED BONDS ISSUING OFFICE State of Iowa Treasurer’s Office Issued on January 22, 2021 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 In 2000, the General Assembly enacted HF 2579 creating the Tobacco Settlement Authority (the “Authority” or “TSA”) in order to provide the framework to allow for the securitization of payments stemming from the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement. During the 2001 legislative session, SF 532 was approved, which authorized the securitization of the Tobacco Settlement Revenues (“TSRs”) and the subsequent sale by the State of 100% of the TSRs to the Authority. In October of 2001 the Authority issued $644,245,000 of Series 2001 Tobacco Settlement Asset-Backed Bonds (the “Series 2001 Bonds”) comprising $604,245,000 of tax-exempt bonds and $40,000,000 of taxable bonds. Seventy-eight percent (78.0%) of the available TSRs was pledged for the repayment of the Series 2001 Bonds. On November 30, 2005, the TSA issued $831,962,030 of Series 2005 Tobacco Settlement Asset- Backed Bonds (the “Series 2005 Bonds”) in order to fully refund the outstanding Series 2001 Bonds, of which $609,052,030 were tax-exempt and $222,910,000 were taxable. The Authority is a body both corporate and politic, created for the sole purpose of purchasing and receiving any assignment of the TSRs and issuing obligations to fund that purchase. The Authority is comprised of three members: the Treasurer of State, the Auditor of State and the Director of the Department of Management. -

Request for Proposal for Senior Underwriter State of Illinois

Request for Proposal for Senior Underwriter State of Illinois 30-Aug-2010 Goldman, Sachs & Co. | 200 West Street | New York, New York 10282 Tel. 212-902-1000 Samuel A. Ramirez & Company, Inc. | 61 Broadway | New York, New York 10006 Tel. 212-248-0500 August 30, 2010 Kevin S. Hovis Governor’s Office of Management and Budget 603 Stratton Building 401 S. Spring Street Springfield, IL 62706 Dear Mr. Hovis: Goldman, Sachs & Co. (“Goldman Sachs”) and Samuel A. Ramirez & Company, Inc. (“Ramirez”) are pleased to submit a joint response to the Railsplitter Tobacco Settlement Authority’s (“Railsplitter” or the “Authority”) Request for Proposals for Senior Managing Underwriter. Goldman Sachs and Ramirez (the “Firms” or the “Team”) are committed to serving the Authority with an experienced group of professionals who will leverage the vast resources of both firms to deliver an extensive marketing process and seamless execution. This cover letter and accompanying proposal respond specifically to your listed requirements including the individuals that will be assigned to executing your transaction and their “tobacco securitization” experience, the Firms’ expertise, the marketing of your transaction, time line and capital resources. We believe that the State has placed the correct scoring emphasis in your response categories on the personnel assigned to this transaction (75 points) and the transaction marketing (75 points) totaling 150 points. In contrast, the other three concerns total only 100 points. We agree with this emphasis due to the significant changes that have occurred over the last several years in both the firms that transact municipal underwriting assignments and their personnel. Given the maturity of the tobacco securitization sector, credit, structuring and security issues (banking) are now well understood and have taken a “back seat” to marketing. -

In Re: Oppenheimer Rochester Funds Group Securities Litigation 09-MD

Case 1:09-md-02063-JLK-KMT Document 250 Filed 01/15/2010 USDC Colorado Page 1 of 80 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLORADO Master Docket No. 09-md-02063-JLK-KMT (MDL Docket No. 2063) IN RE: OPPENHEIMER ROCHESTER FUNDS GROUP SECURITIES LITIGATION This document relates to: In re California Municipal Fund 09-cv-01484-JLK-KMT (Lowe) 09-cv-01485-JLK-KMT (Rivera) 09-cv-01486-JLK-KMT (Tacicinann) 09-cv-01487-JLK-KMT (Milhem) CONSOLIDATED CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT FOR VIOLATION OF THE FEDERAL SECURITIES LAWS AND DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL Case 1:09-md-02063-JLK-KMT Document 250 Filed 01/15/2010 USDC Colorado Page 2 of 80 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. SUMMARY OF THE ACTION 1 A. Misstatements and Omissions in the Registration Statements and Prospectuses 1 B. Violations of the Investment Company Act 5 C. Violations of California Business & Professions Code Sections 17200, Et. Seq. 6 D. Breaches Of Fiduciary Duty 6 E. The Huge Losses Suffered By The Fund 6 II. JURISDICTION AND VENUE 6 III. PARTIES 7 A. Plaintiff. 7 B. Defendants. 8 IV. FACTUAL ALLEGATIONS 12 A. Introduction To The Fund 12 B. Misstatements Relating To The Fund's "Preservation Of Capital" Fundamental Investment Policy 13 C. Misstatements Relating To The Fund's Over-Concentration In The California Real Estate Industry. 20 D. Misstatements Relating To The Fund's Over-Concentration In Junk Bonds And Unrated Bonds. 27 E. Misstatements Relating To The Fund's Investments In Illiquid Securities 30 F. Misstatements Relating To The Fund's Investment In Inverse Floaters. -

(A Public Benefit Corporation of the State of New York) Series 2012A Subordinate Lien Refunding Bonds

NEW ISSUE – BOOK-ENTRY-ONLY In the opinion of each of Hawkins Delafield & Wood LLP and Gonzalez Saggio & Harlan LLP, Co-Bond Counsel, under existing statutes and court decisions (i) interest on the Series 2012A Subordinate Bonds is excluded from gross income for federal income tax purposes under section 103 of the Code, and (ii) interest on the Series 2012A Subordinate Bonds is not treated as a preference item in calculating the federal alternative minimum tax imposed on individuals and corporations under the Code; such interest, however, is included in the adjusted current earnings of certain corporations for purposes of calculating the federal corporate alternative minimum tax imposed on such corporations. Co-Bond Counsel are also of the opinion that interest on the Series 2012A Subordinate Bonds is exempt from personal income taxes imposed by the State of New York or any political subdivision thereof (including The City of New York). Co-Bond Counsel express no opinion regarding any other tax consequences related to the ownership or disposition of, or the accrual or receipt of interest on, the Series 2012A Subordinate Bonds. See “Part 9—TAX MATTERS.” $86,845,000 New York Local Government Assistance Corporation (A Public Benefit Corporation of the State of New York) Series 2012A Subordinate Lien Refunding Bonds Dated: Date of Delivery Due: April 1, as shown on the inside cover The Series 2012A Subordinate Bonds will be issued as registered bonds. The Series 2012A Subordinate Bonds will be issued under a book-entry-only system and will be registered in the name of Cede & Co., as nominee of The Depository Trust Company (“DTC”), New York, New York, which will act as securities depository for the Series 2012A Subordinate Bonds. -

Fiscal Year 2008 Report on Debt Management to the Public Finance Management Board

Fiscal Year 2008 Report on Debt Management To the Public Finance Management Board October 2009 State of Rhode Island And Providence Plantations OFFICE OF THE GENERAL TREASURER FRANK T. CAPRIO GENERAL TREASURER Table of Contents Section Page 1. 2008 Findings _________________________________________________________ 1 2. Rhode Island State Debt _________________________________________________ 8 3. Classification and Analysis of State Debt __________________________________ 10 4. Debt Policies and Practices ______________________________________________ 20 5. Recommended Priorities and Issues for 2009 and 2010 ________________________ 26 Exhibit A. Schedule of Tax-Supported Debt B. Recent Credit Rating Reports C. Schedule of Debt Issuances SECTION 1 2008 Findings The 2008 Report includes the following: Φ Analysis of current State debt position and trends. Φ Status report on the implementation of debt management methods and policies. Φ Evaluation of projected new debt issuance in compliance with the Public Finance Management Board’s (“PFMB”) adopted Credit Guidelines. Φ Information about outstanding debt issued by State-related agencies and summary information on local government debt position and trends. The principal findings of this report are summarized below. Rhode Island’s Debt Burden Remains Moderately High Rhode Island’s debt levels continue to improve, but are still relatively high, as evidenced by the following statistics provided by a Moody’s Investor Service Special Comment Report, April 2008 and the FY10 Capital Budget: • Rhode Island ranks 12th highest among all states in Net Tax Supported Debt as a percent of personal income, at 4.5% (based on Moody’s calculations and 2007 personal income). • Rhode Island ranks 9th highest among all states in Net Tax Supported Debt per capita at $1,812 (based on Moody’s calculations). -

Ten-Year Capital Strategy, Fiscal Years 2002-2011

The City of New York Fiscal Years 2002-2011 Rudolph W. Giuliani, Mayor Ten-Year Capital Strategy Office of Management and Budget Department of City Planning Adam L. Barsky, Director Joseph B. Rose, Director April, 2001 This page intentionally left blank Ten-Year Capital Strategy Summary Cover Photo, City of Bridges, by Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani This page intentionally left blank Ten Year Capital Strategy Overview his Strategy provides a total of $54.4 billion in capital funding over the next ten years. TG.O. funded commitments will total $36.5 billion through 2011 as compared to $35.3 billion in the City’s 2002 Preliminary Ten-Year Capital Strategy. In order to keep the amount of planned general obligation debt within the constitutional debt limit, the capital program will be supported by $3.7 billion in financing from the New York City Transitional Finance Authority and TSASC, Inc. The City will also use $2.8 billion financed by the Dormitory Authority of the State of New York and other lease financing sources. The Ten-Year Capital Strategy provides over $13.3 billion for the construction, reconstruction, rehabilitation and modernization of the City’s schools. In addition, $12.0 billion is allocated for transportation and transit projects, $12.2 billion for water and sewer and sanitation systems, and $7.4 billion is devoted to parks, housing and economic development projects. i The Ten Year Capital Strategy 2002 - 2011 Totals $54.4 Billion in All Funds ($ in billions) Environmental Protection $9.3 Bridges & Highways $10.6 17% 19% Infrastructure -

U.S. State Tobacco Settlement Revenue Securitizations

U.S. State Tobacco Settlement Revenue Securitizations Joshua Cain The Leonard N. Stern School of Business Glucksman Institute for Research in Securities Markets Faculty Advisor: Robert Whitelaw April 3, 2017 1 I. INTRODUCTION Tobacco settlement securitizations, also known as tobacco bonds, are a class of securities backed by the ongoing payments from a 1998 civil settlement with U.S. tobacco companies. States began to issue these bonds in 2000, and, as the market for them matured, twenty states and territories (as well as some counties and cities in certain states), executed securitization transactions. Bloomberg quoted the size of this market as $34 billion as of May 2016. (Chappatta, 2016) Today, many of these bonds are distressed, with bond ratings well into non-investment grade, or "junk", territory. The underlying reason for this is relatively simple: the settlement payments that back the bonds have been significantly lower than forecasted, mostly due to faster declines in cigarette consumption than the forecasts assumed. However, the credit outlook varies widely from bond to bond. In 2015, for example, Moody's announced ratings actions on a number of tobacco bonds, issuing both upgrades and downgrades. (Moody's Global Credit Research, 2015) The ratings issued ranged all the way from Aaa (sf) (Moody's highest category for structured finance) to Caa1 (sf) (seven notches below investment-grade). Since all tobacco settlement securitizations are backed by the same underlying cash flow, differences in structure, mainly those that affect coverage and seniority/payment priority, are the primary source of this variance in credit quality. Clearly, the relative aggressiveness and complexity of different tobacco bonds has had a real effect on their economics.