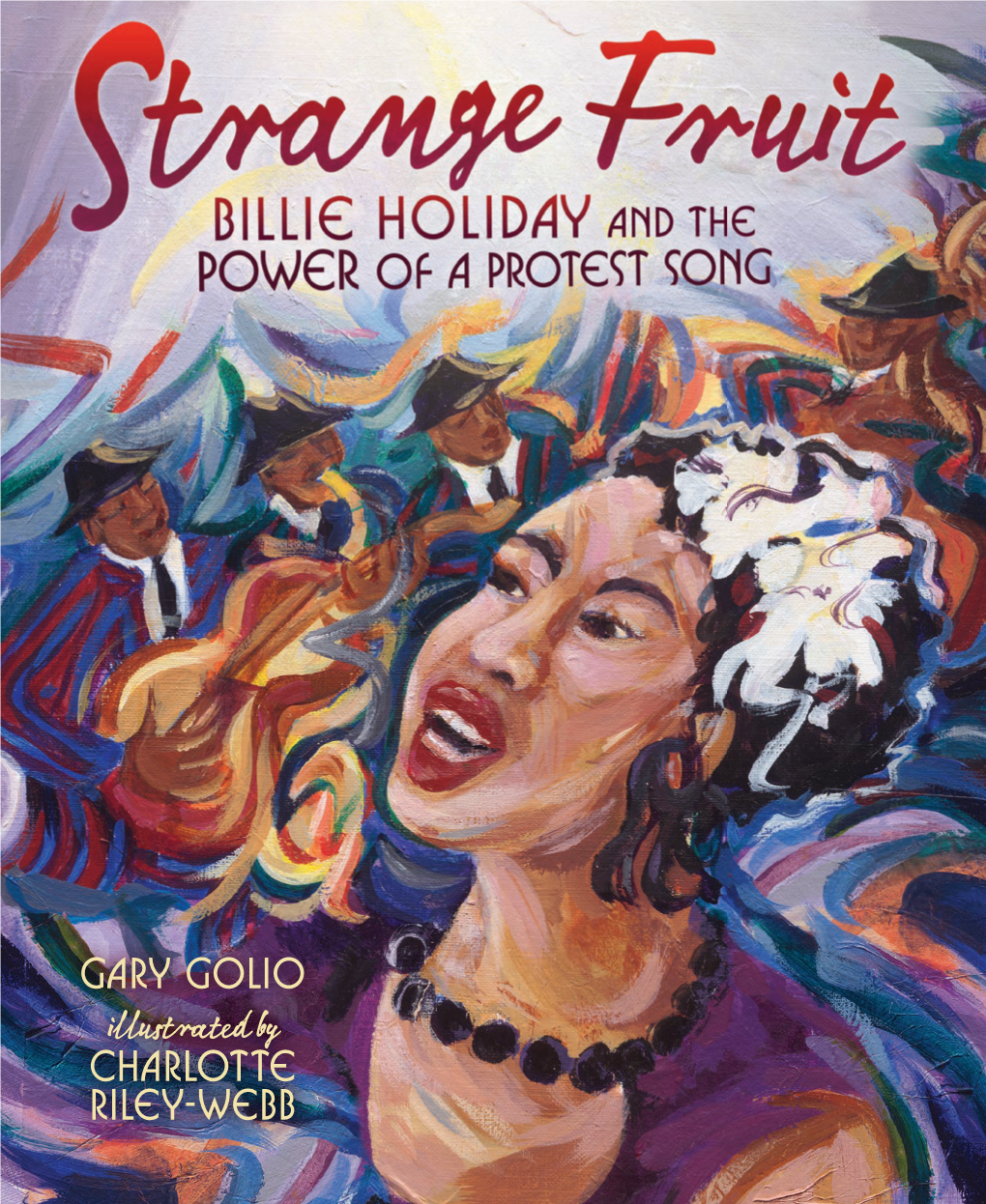

Gary Golio Charlotte Riley-Webb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67

Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 Marc Howard Medwin A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: David Garcia Allen Anderson Mark Katz Philip Vandermeer Stefan Litwin ©2008 Marc Howard Medwin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MARC MEDWIN: Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 (Under the direction of David F. Garcia). The music of John Coltrane’s last group—his 1965-67 quintet—has been misrepresented, ignored and reviled by critics, scholars and fans, primarily because it is a music built on a fundamental and very audible disunity that renders a new kind of structural unity. Many of those who study Coltrane’s music have thus far attempted to approach all elements in his last works comparatively, using harmonic and melodic models as is customary regarding more conventional jazz structures. This approach is incomplete and misleading, given the music’s conceptual underpinnings. The present study is meant to provide an analytical model with which listeners and scholars might come to terms with this music’s more radical elements. I use Coltrane’s own observations concerning his final music, Jonathan Kramer’s temporal perception theory, and Evan Parker’s perspectives on atomism and laminarity in mid 1960s British improvised music to analyze and contextualize the symbiotically related temporal disunity and resultant structural unity that typify Coltrane’s 1965-67 works. -

The Strange Fruit of American Political Development

Politics, Groups, and Identities ISSN: 2156-5503 (Print) 2156-5511 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rpgi20 The Strange Fruit of American Political Development Megan Ming Francis To cite this article: Megan Ming Francis (2018) The Strange Fruit of American Political Development, Politics, Groups, and Identities, 6:1, 128-137, DOI: 10.1080/21565503.2017.1420551 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2017.1420551 Published online: 12 Jan 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 3185 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 3 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rpgi20 POLITICS, GROUPS, AND IDENTITIES, 2018 VOL. 6, NO. 1, 128–137 https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2017.1420551 DIALOGUE: AMERICAN POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT IN THE ERA OF BLACK LIVES MATTER The Strange Fruit of American Political Development Megan Ming Francis Department of Political Science, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY What is the relationship between black social movements, state Received 18 December 2017 violence, and political development in the United States? Today, Accepted 19 December 2017 this question is especially important given the staggering number KEYWORDS of unarmed black women and men who have been killed by the American Political police. In this article, I explore the degree to which American Development; black politics; Political Development (APD) scholarship has underestimated the civil rights; law; social role of social movements to shift political and constitutional movements; Black Lives development. I then argue that studying APD through the lens of Matter Black Lives Matter highlights the need for a sustained engagement with state violence and social movements in analyses of political and constitutional development. -

AN ANALYSIS of the MUSICAL INTERPRETATIONS of NINA SIMONE by JESSIE L. FREYERMUTH B.M., Kansas State University, 2008 a THESIS S

AN ANALYSIS OF THE MUSICAL INTERPRETATIONS OF NINA SIMONE by JESSIE L. FREYERMUTH B.M., Kansas State University, 2008 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MUSIC Department of Music College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2010 Approved by: Major Professor Dale Ganz Copyright JESSIE L. FREYERMUTH 2010 Abstract Nina Simone was a prominent jazz musician of the late 1950s and 60s. Beyond her fame as a jazz musician, Nina Simone reached even greater status as a civil rights activist. Her music spoke to the hearts of hundreds of thousands in the black community who were struggling to rise above their status as a second-class citizen. Simone’s powerful anthems were a reminder that change was going to come. Nina Simone’s musical interpretation and approach was very unique because of her background as a classical pianist. Nina’s untrained vocal chops were a perfect blend of rough growl and smooth straight-tone, which provided an unquestionable feeling of heartache to the songs in her repertoire. Simone also had a knack for word painting, and the emotional climax in her songs is absolutely stunning. Nina Simone did not have a typical jazz style. Critics often described her as a “jazz-and-something-else-singer.” She moved effortlessly through genres, including gospel, blues, jazz, folk, classical, and even European classical. Probably her biggest mark, however, was on the genre of protest songs. Simone was one of the most outspoken and influential musicians throughout the civil rights movement. Her music spoke to the hundreds of thousands of African American men and women fighting for their rights during the 1960s. -

Kronos Quartet Performing Three from Its Fifty for the Future Initiative, Including the World Premiere of New Work by Anna Meredith

CONTACT: Louisa Spier Jeanette Peach Cal Performances Cal Performances (510) 643-6714 (510) 642-9121 [email protected] [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: November 10, 2016 Press Room CAL PERFORMANCES AT UC BERKELEY PRESENTS KRONOS QUARTET PERFORMING THREE FROM ITS FIFTY FOR THE FUTURE INITIATIVE, INCLUDING THE WORLD PREMIERE OF NEW WORK BY ANNA MEREDITH COMMEMORATING THE CENTENNIAL OF THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE, MARY KOUYOUMDJIAN’S SILENT CRANES RECEIVES BAY AREA PREMIERE SATURDAY, DECEMBER 3, 2016 Berkeley, November 10, 2016 — Cal Performances welcomes back the Kronos Quartet for a concert featuring three works by composers from Fifty for the Future: The Kronos Learning Repertoire, on Saturday, December 3, at 8pm in Zellerbach Hall. Through its Fifty for the Future initiative, Kronos is commissioning a collection of 50 new works—10 per year for five years—from an eclectic group of 50 composers (25 men and 25 women); the new works explore contemporary approaches to the string quartet, designed for student players and emerging professional ensembles. Cal Performances is a major project partner for Fifty for the Future, which aligns closely with its Berkeley RADICAL initiative to cultivate artistic literacy in future generations. Of Fifty for the Future, Kronos Quartet artistic director, violinist and founder David Harrington told NPR, “What I hope will happen is that the art form is just going to expand. And the explorations that will be possible from this body of work will just bring a lot of new energy into the field.” The score for each of Kronos’ Fifty for the Future commissions will be made available to musicians free of charge, along with accompanying digital learning materials, recordings, and performance notes. -

Sammy Figueroa Full

Sammy Figueroa has long been regarded as one of the world’s great musicians. As a much-admired percussionist he provided the rhythmical framework for hundreds of hits and countless recordings. Well-known for his versatility and professionalism, he is equally comfortable in a multitude of styles, from R & B to rock to pop to electronic to bebop to Latin to Brazilian to New Age. But Sammy is much more than a mere accompanist: when Sammy plays percussion he tells a story, taking the listener on a journey, and amazing audiences with both his flamboyant technique and his subtle nuance and phrasing. Sammy Figueroa is now considered to be the most likely candidate to inherit the mantles of Mongo Santamaria and Ray Barretto as one of the world’s great congueros. Sammy Figueroa was born in the Bronx, New York, the son of the well-known romantic singer Charlie Figueroa. His first professional experience came at the age of 18, while attending the University of Puerto Rico, with the band of bassist Bobby Valentin. During this time he co-founded the innovative Brazilian/Latin group Raices, which broke ground for many of today’s fusion bands. Raices was signed to a contract with Atlantic Records and Sammy returned to New York, where he was discovered by the great flautist Herbie Mann. Sammy immediately became one of the music world’s hottest players and within a year he had appeared with John McLaughlin, the Brecker Brothers and many of the world’s most famous pop artists. Since then, in a career spanning over thirty years, Sammy has played with a -

Strange Fruit

Get hundreds more LitCharts at www.litcharts.com Strange Fruit antithetical to the South's purported values. The poem thus SUMMARY forcefully argues that no society can call itself civil and also be capable of acts like lynching; the South can’t be an idyllic The trees in the southern United States hang heavy with an “pastoral” place if black people’s corpses swing in the breeze. unusual fruit. These trees have blood on their leaves and at According to the poem, notions of progress and civilization are their roots. The dead bodies of black lynching victims sway nothing but hollow lies if such racism is allowed to thrive. back and forth in the gentle southern wind; these bodies are the strange fruit that hang from the branches of poplar trees. And, importantly, this racist hatred affects the entire tree—which becomes covered in blood “on the leaves” “at Picture the natural beauty and chivalry of the American South, and the root.” Just as a tree must suck up water from the ground where corpses hang with swollen eyes and contorted mouths. and spread it all the way through its branches, the poem implies The sweet, fresh smell of magnolia flowers floats on the air, that the "blood" shed by racism works its way through until suddenly interrupted by the smell of burning flesh. humanity. Lynching is thus a failure of humanity that results in Crows will eat the flesh from these bodies. The rain will fall on the rotting of the human family tree. them, the wind will suck them dry, and the sun will rot them. -

The Art of Lyric Improvisation

THE ART OF LYRIC IMPROVISATION A Comparative Study of Two Renowned Jazz Singers ______________________________________________ A thesis in partial fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Music in the University of Canterbury by S. J. de Jong University of Canterbury 2008 _________________________________________ de Jong i Table of Contents THE ART OF LYRIC IMPROVISATION ........................................................................................................ i Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................................... i Abstract .................................................................................................................................................... iii Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: Historical and Biographical Overviews ....................................................................................... 5 1.1: Jazz Historical Background ................................................................................................................ 5 1.2: “Sometimes I’m Happy” .................................................................................................................... 6 1.3: Sarah Vaughan .................................................................................................................................. -

![European Journal of American Studies, 11-2 | 2016, « Summer 2016 » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 11 Août 2016, Consulté Le 08 Juillet 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0640/european-journal-of-american-studies-11-2-2016-%C2%AB-summer-2016-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-11-ao%C3%BBt-2016-consult%C3%A9-le-08-juillet-2021-770640.webp)

European Journal of American Studies, 11-2 | 2016, « Summer 2016 » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 11 Août 2016, Consulté Le 08 Juillet 2021

European journal of American studies 11-2 | 2016 Summer 2016 Édition électronique URL : https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/11535 DOI : 10.4000/ejas.11535 ISSN : 1991-9336 Éditeur European Association for American Studies Référence électronique European journal of American studies, 11-2 | 2016, « Summer 2016 » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 11 août 2016, consulté le 08 juillet 2021. URL : https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/11535 ; DOI : https:// doi.org/10.4000/ejas.11535 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 8 juillet 2021. Creative Commons License 1 SOMMAIRE The Land of the Future: British Accounts of the USA at the Turn of the Nineteenth Century David Seed The Reader in It: Henry James’s “Desperate Plagiarism” Hivren Demir-Atay Contradictory Depictions of the New Woman: Reading Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence as a Dialogic Novel Sevinc Elaman-Garner “Nothing Can Touch You as Long as You Work”: Love and Work in Ernest Hemingway’s The Garden of Eden and For Whom the Bell Tolls Lauren Rule Maxwell People, Place and Politics: D’Arcy McNickle’s (Re)Valuing of Native American Principles John L. Purdy “Why Don’t You Just Say It as Simply as That?”: The Progression of Parrhesia in the Early Novels of Joseph Heller Peter Templeton “The Land That He Saw Looked Like a Paradise. It Was Not, He Knew”: Suburbia and the Maladjusted American Male in John Cheever’s Bullet Park Harriet Poppy Stilley The Writing of “Dreck”: Consumerism, Waste and Re-use in Donald Barthelme’s Snow White Rachele Dini The State You’re In: Citizenship, Sovereign -

The Field Guide to Sponsored Films

THE FIELD GUIDE TO SPONSORED FILMS by Rick Prelinger National Film Preservation Foundation San Francisco, California Rick Prelinger is the founder of the Prelinger Archives, a collection of 51,000 advertising, educational, industrial, and amateur films that was acquired by the Library of Congress in 2002. He has partnered with the Internet Archive (www.archive.org) to make 2,000 films from his collection available online and worked with the Voyager Company to produce 14 laser discs and CD-ROMs of films drawn from his collection, including Ephemeral Films, the series Our Secret Century, and Call It Home: The House That Private Enterprise Built. In 2004, Rick and Megan Shaw Prelinger established the Prelinger Library in San Francisco. National Film Preservation Foundation 870 Market Street, Suite 1113 San Francisco, CA 94102 © 2006 by the National Film Preservation Foundation Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Prelinger, Rick, 1953– The field guide to sponsored films / Rick Prelinger. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-9747099-3-X (alk. paper) 1. Industrial films—Catalogs. 2. Business—Film catalogs. 3. Motion pictures in adver- tising. 4. Business in motion pictures. I. Title. HF1007.P863 2006 011´.372—dc22 2006029038 CIP This publication was made possible through a grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. It may be downloaded as a PDF file from the National Film Preservation Foundation Web site: www.filmpreservation.org. Photo credits Cover and title page (from left): Admiral Cigarette (1897), courtesy of Library of Congress; Now You’re Talking (1927), courtesy of Library of Congress; Highlights and Shadows (1938), courtesy of George Eastman House. -

Old Fashioned Music (W)

Late Night Jazz: Old Fashioned Music (W) Samstag, 09. Dezember 2017, 22.05 - 24.00 Uhr Heute geht man «clubben» und «tanzt ab» wenn vorne der coole DJ hinter seinen Apparaturen steht. In den alten Zeiten waren die Apparaturen Trompeten, Posaunen und Saxophone, die Musiker waren hot und heizten ordentlich ein, im Club oder im Ballroom. Wir feiern eine old fashioned Tanzparty mit Big Bands von Fletcher Henderson bis Artie Shaw und heissen Kapellen mit so schönen Namen wie «Andy Kirk an his Twelve Clouds of Joy» oder «McKinney’s Cotton Pickers»! Redaktion: Beat Blaser Moderation: Annina Salis Louis Armstrong and his Orchestra 1936-1937 Label: Classics Records Track 15: Swing That Music Louis Armstrong and his Orchestra 1934-1936 Label: Classics Records Track 21: The Music Goes Round and Around The definitive Fletcher Henderson (1931) Label: Decca Track 12: Radio Rhythm Fats Waller - Ain't Misbehavin' - Jazz Reference (1939) Label: Dreyfus Jazz Track 9: Your feet's Too Big The Definitive Ella Fitzgerald (1936) Label: Verve Track 2: Vote For Mr. Rhythm Art Tatum 1933-37 (1933) Label: Membran Track 10: Tea for Two Ella Fitzgerald 75th Birthday Celebration - The Original Decca Recordings (1938) Label: MCA Track 1: A-Tisket, A-Tasket McKinney's Cotton Pickers. 1928-1929 Label: Classics Records Track 2: Put it There Irving Berlin - A Hundred Years (1934) Label: CBS Track 9: The Boswell Sisters - Alexander's Ragtime Band Ken Burns Jazz - The Story of America's Music, Disc 1 (1934) Label: Columbia 549 352-2 Track 16: Duke Ellington - The Mooche Billie Holiday: Fine and Mellow - Vol. -

Billie Holiday, “Strange Fruit” (1939)

Billie Holiday, “Strange Fruit” (1939) “Strange Fruit” was written by Abel Meeropol, a white English teacher from New York City, as a protest against the horrors of lynching. Lynching was a practice that involved mob-style execution without trial, most often by hanging, and almost exclusively of African Ameri- cans. Thousands of African Americans were lynched between the end of the Civil War and the 1960s. In spite of the efforts of anti-lynching crusaders such as Ida B. Wells beginning in the 1880s, lynching was never directly addressed by the federal government until the Justice for Lynching Act was passed on December 19, 2018, making lynching a federal crime. Jazz great Billie Holiday recorded “Strange Fruit” in 1939. Her recording company, Columbia Records, re- fused to release it, fearing the response in the South. So Holiday released the al- bum with the Commodore label, where it would go on to become her best-sell- ing record. With its harsh indictment of the Jim Crow south, the song enjoyed a revival during the Civil Rights movement, and has been covered by numerous artists in the years since. Lyric Excerpt Southern trees bear a strange fruit, Blood on the leaves and blood at the root Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze, Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees Pastoral scene of the gallant south The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth Scent of magnolias, sweet and fresh Then the sudden smell of burning flesh Here is fruit for the crows to pluck For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck For the sun to rot, for the trees to drop Here is a strange and bitter crop. -

John Coltrane John Coltrane John Coltrane

THE JOHN COLTRANE THE JOHN COLTRANE QUARTET PLAYS QUARTET PLAYS JOHN COLTRANE JOHN COLTRANE ™ ™ IMPD -214 IMPD -214 The John Coltrane The John Coltrane Quartet Plays Quartet Plays JOHN COLTRANE JOHN COLTRANE Several years ago in the course of reviewing one of his Personnel Several years ago in the course of reviewing one of his Personnel albums I had occasion to remark “that I consider [John] John Coltrane, soprano saxophone, tenor saxophone albums I had occasion to remark “that I consider [John] John Coltrane, soprano saxophone, tenor saxophone Coltrane the outstanding new artist to gain prominence McCoy Tyner, piano Coltrane the outstanding new artist to gain prominence McCoy Tyner, piano during the last half decade.” From my present vantage Jimmy Garrison, bass during the last half decade.” From my present vantage Jimmy Garrison, bass Art Davis, bass (#3, 5 & 6) point, the only regrets I have concerning that statement is point, the only regrets I have concerning that statement is Art Davis, bass (#3, 5 & 6) Elvin Jones, drums Elvin Jones, drums that I was so parsimonious with my praise. Not only is that I was so parsimonious with my praise. Not only is Coltrane the most distinguished jazz performer, in my Original sessions produced by Bob Thiele Coltrane the most distinguished jazz performer, in my Original sessions produced by Bob Thiele opinion, to have emerged since 1950, but more than perhaps Reissue produced by Michael Cuscuna opinion, to have emerged since 1950, but more than perhaps Reissue produced by Michael Cuscuna is realized, his career epitomizes all of the most crucial Recording engineer: Rudy Van Gelder is realized, his career epitomizes all of the most crucial Recording engineer: Rudy Van Gelder 2 developments that have taken place since then.