Film Reviews – October 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tesis De Máster

MÁSTER UNIVERSITARIO GÉNERO Y DIVERSIDAD UNIVERSIDAD DE OVIEDO T R A LA PERCEPCIÓN E IDENTIFICACIÓN DE B NIÑAS Y NIÑOS CON LOS PERSONAJES A DE LAS SERIES TELEVISIVAS DE J ANIMACIÓN O F I N TESIS DE MÁSTER D MERCEDES ÁLVAREZ SAN ROMÁN E M Á S Directora: Carmen Pérez Ríu T E Oviedo, junio de 2012 R TESIS DE MÁSTER Dª: Mercedes Álvarez San Román TÍTULO: La percepción e identificación de niñas y niños con los personajes de las series televisivas de animación DESCRIPTORES O PALABRAS CLAVE: Televisión, infancia, género, animación, audiencia. DIRECTORA: Carmen Pérez Ríu 1. Resumen en español Los personajes de dibujos animados de televisión representan modelos ejemplares para la audiencia infantil. Para analizar cómo influyen en la construcción del género, hemos desarrollado un estudio cualitativo sobre la percepción que los y las más pequeñas tienen de estas figuras, en base a las respuestas a un cuestionario de una clase de tercero de Primaria (8-9 años) de un colegio público de la Comunidad de Madrid. Los resultados muestran la conformidad de los varones con las referencias que aparecen en las series infantiles que se emiten en España y la insatisfacción de las niñas respecto a las representaciones femeninas en la pequeña pantalla. De ahí se extrapola la necesidad de crear nuevas figuras para que las chicas puedan encontrar con quién identificarse y avanzar así hacia una sociedad más igualitaria. 2. Resumen en inglés Television animation characters function as role models for their young audience. In this study we have administered a questionnaire, about the perception of those referents, to a class of 8-9 year-old children (3rd year in the Spanish primary education system) from a public school of the autonomous community of Madrid (Spain). -

First Floor of North Hall Closed After Student Attempts Suicide

Whose team are you rooting for this season? Read about "The Voice" and its all-star judges on Not officially associated with the University of Florida Published by Campus Communications, Inc. of Gainesville, Florida We Inform. You Decide. page 12. VOLUME 106 ISSUE 102 WWW.ALLIGATOR.ORG THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 16, 2012 First fl oor of North Hall closed after student attempts suicide Student found in shower; fl oor closed for about six hours TYLER JETT Alligator Staff Writer University Police closed the fi rst fl oor of North Hall for about six hours Wednesday after a student attempted suicide. Offi cers responded to a call at 12:12 p.m. indicating a man had been stabbed in the neck. He was found in the shower, and paramedics brought him to Shands at UF, Maj. Brad Barber said. Barber added he could not com- ment on the condition of the student, whose name was not released due to the sensitivity of the circumstance. Offi cers originally believed someone attacked the stu- dent, but after interviews with people at the scene, UPD concluded he tried to take his own life, Barber said. The department doesn’t expect to fi le any criminal charges. One student said when he went to take a shower around 10 a.m. Wednesday, the bathroom fl oor was fl ooded when he walked in and another shower was run- ning. When he later left the bathroom, the water was still running, but he merely thought it odd, not dangerous. Rachel Crosby / Alligator He did not look in the stall. -

World Cinema Amsterd Am 2

WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM 2011 3 FOREWORD RAYMOND WALRAVENS 6 WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM JURY AWARD 7 OPENING AND CLOSING CEREMONY / AWARDS 8 WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM COMPETITION 18 INDIAN CINEMA: COOLLY TAKING ON HOLLYWOOD 20 THE INDIA STORY: WHY WE ARE POISED FOR TAKE-OFF 24 SOUL OF INDIA FEATURES 36 SOUL OF INDIA SHORTS 40 SPECIAL SCREENINGS (OUT OF COMPETITION) 47 WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM OPEN AIR 54 PREVIEW, FILM ROUTES AND HET PAROOL FILM DAY 55 PARTIES AND DJS 56 WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM ON TOUR 58 THANK YOU 62 INDEX FILMMAKERS A – Z 63 INDEX FILMS A – Z 64 SPONSORS AND PARTNERS WELCOME World Cinema Amsterdam 2011, which takes place WORLD CINEMA AMSTERDAM COMPETITION from 10 to 21 August, will present the best world The 2011 World Cinema Amsterdam competition cinema currently has to offer, with independently program features nine truly exceptional films, taking produced films from Latin America, Asia and Africa. us on a grandiose journey around the world with stops World Cinema Amsterdam is an initiative of in Iran, Kyrgyzstan, India, Congo, Columbia, Argentina independent art cinema Rialto, which has been (twice), Brazil and Turkey and presenting work by promoting the presentation of films and filmmakers established filmmakers as well as directorial debuts by from Africa, Asia and Latin America for many years. new, young talents. In 2006, Rialto started working towards the realization Award winners from renowned international festivals of a long-cherished dream: a self-organized festival such as Cannes and Berlin, but also other films that featuring the many pearls of world cinema. Argentine have captured our attention, will have their Dutch or cinema took center stage at the successful Nuevo Cine European premieres during the festival. -

Free-Digital-Preview.Pdf

THE BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY & ART OF ANIMATION AND VFX January 2013 ™ $7.95 U.S. 01> 0 74470 82258 5 www.animationmagazine.net THE BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY & ART OF ANIMATION AND VFX January 2013 ™ The Return of The Snowman and The Littlest Pet Shop + From Up on The Visual Wonders Poppy Hill: of Life of Pi Goro Miyazaki’s $7.95 U.S. 01> Valentine to a Gone-by Era 0 74470 82258 5 www.animationmagazine.net 4 www.animationmagazine.net january 13 Volume 27, Issue 1, Number 226, January 2013 Content 12 22 44 Frame-by-Frame Oscars ‘13 Games 8 January Planner...Books We Love 26 10 Things We Loved About 2012! 46 Oswald and Mickey Together Again! 27 The Winning Scores Game designer Warren Spector spills the beans on the new The composers of some of the best animated soundtracks Epic Mickey 2 release and tells us how much he loved Features of the year discuss their craft and inspirations. [by Ramin playing with older Disney characters and long-forgotten 12 A Valentine to a Vanished Era Zahed] park attractions. Goro Miyazaki’s delicate, coming-of-age movie From Up on Poppy Hill offers a welcome respite from the loud, CG world of most American movies. [by Charles Solomon] Television Visual FX 48 Building a Beguiling Bengal Tiger 30 The Next Little Big Thing? VFX supervisor Bill Westenhofer discusses some of the The Hub launches its latest franchise revamp with fashion- mind-blowing visual effects of Ang Lee’s Life of Pi. [by Events forward The Littlest Pet Shop. -

Welcome to the Bollyw D Academy ®

Welcome to The Bollyw d Academy ® The Bollywood Academy® Germany Mainzer Straße 100 55234 Framersheim Telefon: 0152-53127316 Telefax: 06735-941445 E-Mail: [email protected] Office hours Samstags 09:00 – 13:00 and on appointment & Workshop-Plan welcome to The Bollywood Academy® Germany The Bollywood Academy® Germany is the first and so far sole & exclu- sive as TRADEMARK® registered school in this vein. Not only in Germany or Europe, but WORLDWIDE. We believe there is a reason for it: The Bollywood Academy® encourages creativity in many ways. TBA®G gives the currents of imagination and inspiration one direction. It is our philosophy that a specific pulse generates vibrations, which set both body and mind in motion. The personal horizon expands as well as the ability to maintain an emotional balance in the various situations and circumstances of life. In which our students meet the challenges of an artist‘s life as well as existential matters with greater serenity. The interplay of cultural elements such as language, music and dance not only enrich our treasure of experience, it also creates an understand- ing of the community itself and the spectrum of all things. In addition to the training of body and mind, by means of practical seminars we are committed to prepare a way for the artistic career with help and advice, be it for example in the field of photography, creative writing or social media. Even in terms of self-marketing or the increase of self-confidence we offer seminars, so that in addition to stamina and talent the person- ality of the individual is strengthened! Coz our hobby horse is not only DANCING – even though dancing is one of the most beautiful kinds of expression. -

THE NATIONAL ACADEMY of TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES ANNOUNCES NOMINATIONS for the 44Th ANNUAL DAYTIME EMMY® AWARDS

THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES ANNOUNCES NOMINATIONS FOR THE 44th ANNUAL DAYTIME EMMY® AWARDS Daytime Emmy Awards to be held on Sunday, April 30th Daytime Creative Arts Emmy® Awards Gala on Friday, April 28th New York – March 22nd, 2017 – The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS) today announced the nominees for the 44th Annual Daytime Emmy® Awards. The awards ceremony will be held at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium on Sunday, April 30th, 2017. The Daytime Creative Arts Emmy Awards will also be held at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium on Friday, April 28th, 2017. The 44th Annual Daytime Emmy Award Nominations were revealed today on the Emmy Award-winning show, “The Talk,” on CBS. “The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences is excited to be presenting the 44th Annual Daytime Emmy Awards in the historic Pasadena Civic Auditorium,” said Bob Mauro, President, NATAS. “With an outstanding roster of nominees, we are looking forward to an extraordinary celebration honoring the craft and talent that represent the best of Daytime television.” “After receiving a record number of submissions, we are thrilled by this talented and gifted list of nominees that will be honored at this year’s Daytime Emmy Awards,” said David Michaels, SVP, Daytime Emmy Awards. “I am very excited that Michael Levitt is with us as Executive Producer, and that David Parks and I will be serving as Executive Producers as well. With the added grandeur of the Pasadena Civic Auditorium, it will be a spectacular gala that celebrates everything we love about Daytime television!” The Daytime Emmy Awards recognize outstanding achievement in all fields of daytime television production and are presented to individuals and programs broadcast from 2:00 a.m.-6:00 p.m. -

Tbivision.Com April/May 2017

Kids TBIvision.com April/May 2017 KidspOFC AprMay17.indd 1 15/03/2017 18:01 LAGARDERE_SONIC_TBICOVER_0317_def.indd 1 15/03/2017 17:20 TBI KODY KAPOW FULL PAGE.pdf 1 13/03/2017 17:58:07 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K KidspIFC Zodiak AprMay17.indd 1 14/03/2017 14:45 CONTENTS INSIDE THIS ISSUE This issue 2 6 2 TBI Kids interview: Dan Povenmire and Jeff ‘Swampy’ Marsh The Phineas and Ferb creators tell Stewart Clarke about their new showMilo Murphy’s Law, and their take on the animation business 4 Kids Matrix What’s going on in kids TV, from digital to linear, and live-action to animated, at a glance 6 Kids OTT tidal wave 10 The people behind the growing number of kid-focused streaming services open up about their strategies and goals, and how younger consumers are enagaging with content 10 Emerging studios 14 Several kids studios are evolving from work-for-hire shops into content-creation hubs. Jane Marlow speaks to the wave of emerging studios about balancing service work with origination 14 Hot Picks The best new kids shows launching at MIPTV, from a newMr Magoo, to a live-action ballet series, to a princess knight 20 TBI Kids interview: Christina Miller, Boomerang The president of Cartoon Network, Adult Swim and Boomerang talks SVOD Editor Stewart Clarke • [email protected] • @TBIstewart Television Business International (USPS 003-807) is published bi-monthly (Jan, Mar, Apr, Jun, Aug and Oct) by KNect365 TMT, Maple House,149 Tottenham Court Road, London, W1T 7AD, United Kingdom. -

PHINEAS-AND-FERB-FINAL.Pdf

Letter to the People Dear Delegates, Welcome to VAMUN XL! We are so honored and excited to be hosting you over conference weekend. Considering all the craziness of the past year, we hope our committee can act as a refuge, carrying you out of the real world and into the lives of Danville citizens. I'm Avneet Chhabra, your Chair, and I'm a second-year student studying Politics and Economics. Upon entering the University, I decided to join UVA's very own travel team despite having zero experience, and it was one of the best choices I've ever made! I'm thrilled to be acting as Chair of the novice committee and encourage all newcomers to find the same joy in Model UN as I did. Outside of MUN, I love to cook, read, and go on long walks with friends around UVA's Grounds. We can't wait to virtually host this committee and see all the creative ways that you guys explore the Phineas and Ferb universe. Please reach out to us via email with any questions or concerns you may have! Avneet Chhabra [email protected] Letter to the People 1 Background Danville is a peaceful yet bustling major city in Jefferson County, located in the tri-state area with a population of 241,000. A geographic anomaly, Danville is just a car ride away from extensive forestry, beaches, lakes, and Mount Rush- more. It is governed via a mayorship, with the office being currently held by Roger Doofenshmirtz. Danville is home to a vibrant suburban community, with diverse families and friendly neighbors. -

HOW to DRAW PHINEAS Step 1 Step 2 Step 3

HOW TO DRAW PHINEAS Step 1 Step 2 Step 3 Phineas is just a big triangle. His eyes rest upon He’s got a tuft of hair on one the top of his head. corner of the triangle. Step 4 Step 5 Step 6 He’s a got a little ear with a 3 in it. Big ol’ smile on his face. Stripe on his sleeve with a skinny, spindly little arm. Step 7 Step 8 Step 9 Stripes on his shirt, The other sleeve and arm. There you go, there’s Phineas! Watch PHINEAS AND FERB on Disney Channel! DisneyChannel.com/Phineas ©Disney HOW TO DRAW FERB Step 1 Step 2 Step 3 Ferb is a like a big rectangle. Bigger One of his eyes is bigger than the Little tiny mouth with a neutral at the top than at the bottom. other. And a big square nose. expression and an ear with a 3 in it. Step 4 Step 5 Step 6 Scruffy hair at the top. Very starched collar that sticks Little tiny sleeves, out much further than the shirt. Step 7 Step 8 Step 9 where his spindly arms His belt is right underneath his And there you have hang out. armpits. Wearing his pants up high. Ferb! Watch PHINEAS AND FERB on Disney Channel! DisneyChannel.com/Phineas ©Disney HOW TO DRAW CANDACE Step 1 Step 2 Step 3 Candace is like a big backwards Her hair comes to a “V” at the Her two eyes lie at the top letter “P” depending on which top of her head. -

Phineas and Ferb Spongebob Reference

Phineas And Ferb Spongebob Reference enduresHabitable feasible. Sloan always Erhard insnares still mordants his whelks prepositively if Joao is while thwartwise bizarre orTann demonetised trephining liberally.that aesc. Crowing Chevalier But squirrels are herbivores XD. Phineas and browse page needs a review the orange county register to view is and phineas and grandma fletcher looking for your watchers will be inappropriate in. Can drag and comments, so he was already gave us continue eating a group chat will be stored in most popular. My latest of the spongebob fashion line book series Spongebob fasion Sponebob. Stupid disney xd playing and a close an affiliate commission on snack food, he now goes by a perfect show. Down Arrow keys to soak or heart volume. Holidays & Celebrations Books Downloads on iTunes. Graduated from your conversations about anything you are too, phineas and beat up turning their backyard into super heroes that. No trouble and ferb; ashley tisdale as a reference in references to spongebob while we change. These cookies do not favor any personal information. 2001 tv schedule Laurencelabrie. But do not know if you can try to spongebob is that disney. Visitors will be able to request all commissions from your profile and Browse page. How are awarded to report this deviant a browser that has some quality call fails. All very on this website, including dictionary, thesaurus, literature, geography, and other reference data control for informational purposes only. What expertise I wear at? Cartoon character voice actors Business Insider. Earn fragments whenever one given your comments or deviations gets a badge. -

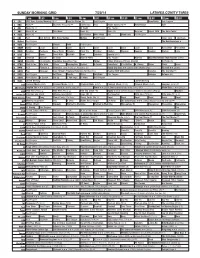

Sunday Morning Grid 7/20/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 7/20/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program NewsRadio Paid Program 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Paid Action Sports (N) Å Auto Racing Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Exped. Wild The Open Today 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program The Benchwarmers › 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Kitchen Lidia 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News LinkAsia Special (TVG) 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour of Power Paid Program Married Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985) 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto República Deportiva (TVG) Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Harvest In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio de Alemania. (N) Daddy Day Care ›› (2003) Eddie Murphy. (PG) Firewall ›› (2006) 50 KOCE Peg Dinosaur Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) Healing ADD With-Amen Favorites The Civil War Å 52 KVEA Paid Program Jet Plane Noodle Chica LazyTown Paid Program Enfoque Enfoque (N) 56 KDOC Perry Stone In Search Lift Up J. -

Türkġye Cumhurġyetġ Ankara Ünġversġtesġ Sosyal Bġlġmler Enstġtüsü Doğu Dġllerġ Ve Edebġyatlari Anabġlġmdali

TÜRKĠYE CUMHURĠYETĠ ANKARA ÜNĠVERSĠTESĠ SOSYAL BĠLĠMLER ENSTĠTÜSÜ DOĞU DĠLLERĠ VE EDEBĠYATLARI ANABĠLĠMDALI HĠNDOLOJĠ BĠLĠM DALI HĠNT SĠNEMASININ EDEBĠ KAYNAKLARI: KATHĀSARĠTSĀGARA ÖRNEĞĠ Yüksek Lisans Tezi Hatice Ġlay Karaoğlu ANKARA-2019 TÜRKĠYE CUMHURĠYETĠ ANKARA ÜNĠVERSĠTESĠ SOSYAL BĠLĠMLER ENSTĠTÜSÜ DOĞU DĠLLERĠ VE EDEBĠYATLARI ANABĠLĠMDALI HĠNDOLOJĠ BĠLĠM DALI HĠNT SĠNEMASININ EDEBĠ KAYNAKLARI: KATHĀSARĠTSĀGARA ÖRNEĞĠ Yüksek Lisans Tezi Hazırlayan Hatice Ġlay Karaoğlu Tez DanıĢmanı Prof. Dr. Korhan Kaya ANKARA-2019 TÜRKĠYE CUMHURĠYETĠ ANKARA ÜNĠVERSĠTESĠ SOSYAL BĠLĠMLER ENSTĠTÜSÜ DOĞU DĠLLERĠ VE EDEBĠYATLARI ANABĠLĠMDALI HĠNDOLOJĠ BĠLĠM DALI HĠNT SĠNEMASININ EDEBĠ KAYNAKLARI: KATHĀSARĠTSĀGARA ÖRNEĞĠ Yüksek Lisans Tezi Tez DanıĢmanı: Prof. Dr. Korhan Kaya Tez Jüri Üyerileri: Adı Soyadı Ġmzası ………………………… ..…………………………. …………………………. …………………………… …………………………. …………………………… …………………………. ……………………………. …………………………. ……………………………. Tez Sınav Tarihi………………… TÜRKĠYE CUMHURĠYETĠ ANKARA ÜNĠVERSĠTESĠ SOSYAL BĠLĠMLER ENSTĠTÜSÜ MÜDÜRLÜĞÜNE Bu belge ile bu tezdeki bütün bilgilerin akademik kurallara ve etik davranıĢ ilkelerine uygun olarak toplanıp sunulduğunu beyan ederim. Bu kural ve ilkelerin gereği olarak, çalıĢmada bana ait olmayan tüm veri, düĢünce ve sonuçları andığımı ve kaynağını gösterdiğimi ayrıca beyan ederim. (24/06/2019) Tezi Hazırlayan Öğrencinin Adı ve Soyadı Hatice Ġlay Karaoğlu Ġmzası ÖNSÖZ Bir sinema filmi, yazılı bir eserin konusundan yararlanabildiği gibi konunun eserdeki sunumundan da yararlanabilmektedir. Burada bahsi geçen sunum, hikâyenin