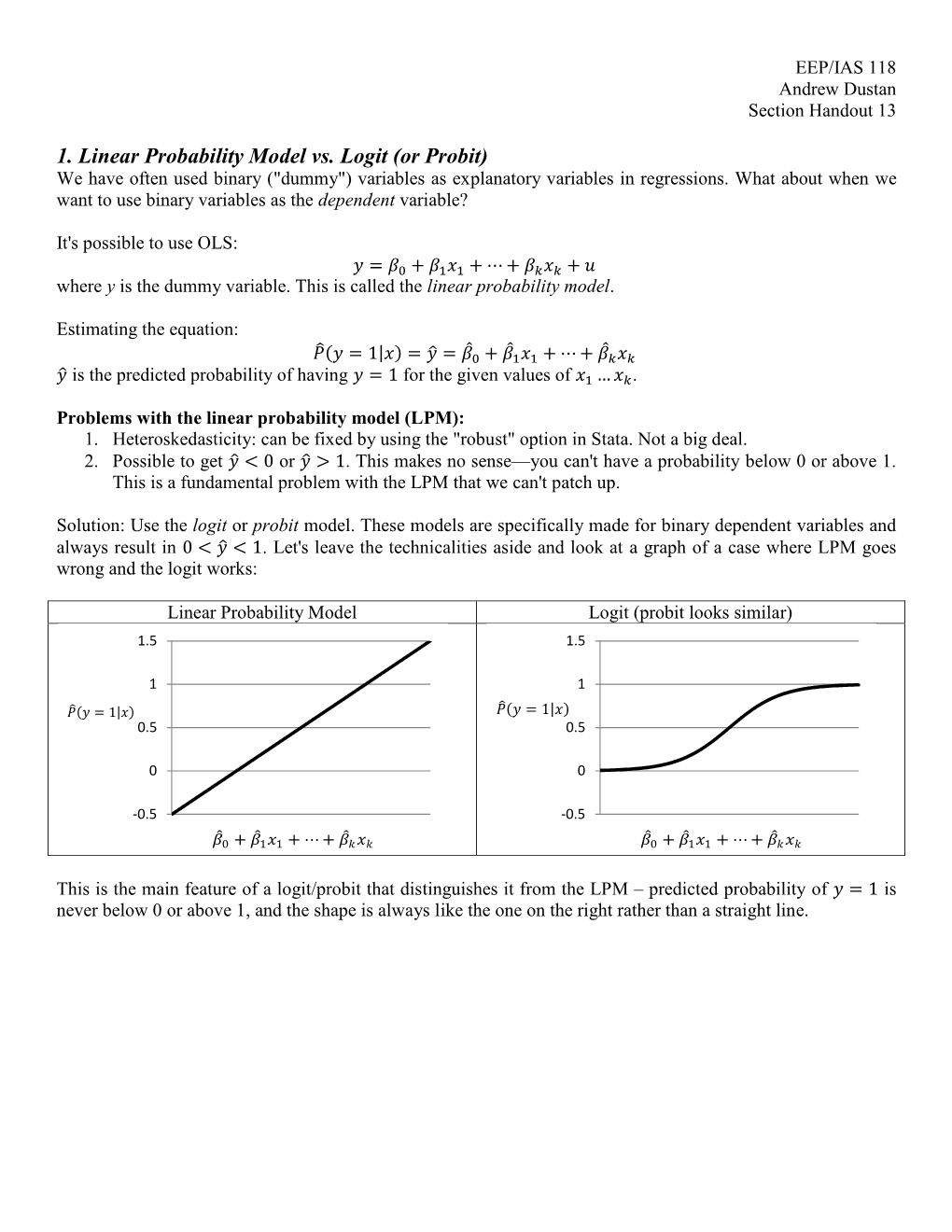

1. Linear Probability Model Vs. Logit (Or Probit) We Have Often Used Binary ("Dummy") Variables As Explanatory Variables in Regressions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Instrumental Variables Probit Estimator Using Gretl

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics An Instrumental Variables Probit Estimator using gretl Lee C. Adkins Professor of Economics, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK 74078 [email protected] Abstract. The most widely used commercial software to estimate endogenous probit models offers two choices: a computationally simple generalized least squares estimator and a maximum likelihood estimator. Adkins [1, -. com%ares these estimators to several others in a Monte Carlo study and finds that the 1LS estimator performs reasonably well in some circumstances. In this paper the small sample properties of the various estimators are reviewed and a simple routine us- ing the gretl software is given that yields identical results to those produced by Stata 10.1. The paper includes an example estimated using data on bank holding companies. 1 Introduction 4atchew and Griliches +,5. analyze the effects of various kinds of misspecifi- cation on the probit model. Among the problems explored was that of errors- in-variables. In linear re$ression, a regressor measured with error causes least squares to be inconsistent and 4atchew and Griliches find similar results for probit. Rivers and 7#ong [14] and Smith and 8lundell +,9. suggest two-stage estimators for probit and tobit, respectively. The strategy is to model a con- tinuous endogenous regressor as a linear function of the exogenous regressors and some instruments. Predicted values from this regression are then used in the second stage probit or tobit. These two-step methods are not efficient, &ut are consistent. -

An Empirical Analysis of Factors Affecting Honors Program Completion Rates

An Empirical Analysis of Factors Affecting Honors Program Completion Rates HALLIE SAVAGE CLARION UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA AND T H E NATIONAL COLLEGIATE HONOR COUNCIL ROD D. RAE H SLER CLARION UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA JOSE ph FIEDOR INDIANA UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA INTRODUCTION ne of the most important issues in any educational environment is iden- tifying factors that promote academic success. A plethora of research on suchO factors exists across most academic fields, involving a wide range of student demographics, and the definition of student success varies across the range of studies published. While much of the research is devoted to looking at student performance in particular courses and concentrates on examina- tion scores and grades, many authors have directed their attention to student success in the context of an entire academic program; student success in this context usually centers on program completion or graduation and student retention. The analysis in this paper follows the emphasis of McKay on the importance of conducting repeated research on student completion of honors programs at different universities for different time periods. This paper uses a probit regression analysis as well as the logit regression analysis employed by McKay in order to determine predictors of student success in the honors pro- gram at a small, public university, thus attempting to answer McKay’s call for a greater understanding of honors students and factors influencing their suc- cess. The use of two empirical models on completion data, employing differ- ent base distributions, provides more robust statistical estimates than observed in similar studies 115 SPRING /SUMMER 2014 AN EMPIRI C AL ANALYSIS OF FA C TORS AFFE C TING COMPLETION RATES PREVIOUS LITEratURE The early years of our research was concurrent with the work of McKay, who studied the 2002–2005 entering honors classes at the University of North Florida and published his work in 2009. -

Application of Random-Effects Probit Regression Models

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology Copyright 1994 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 1994, Vol. 62, No. 2, 285-296 0022-006X/94/S3.00 Application of Random-Effects Probit Regression Models Robert D. Gibbons and Donald Hedeker A random-effects probit model is developed for the case in which the outcome of interest is a series of correlated binary responses. These responses can be obtained as the product of a longitudinal response process where an individual is repeatedly classified on a binary outcome variable (e.g., sick or well on occasion t), or in "multilevel" or "clustered" problems in which individuals within groups (e.g., firms, classes, families, or clinics) are considered to share characteristics that produce similar responses. Both examples produce potentially correlated binary responses and modeling these per- son- or cluster-specific effects is required. The general model permits analysis at both the level of the individual and cluster and at the level at which experimental manipulations are applied (e.g., treat- ment group). The model provides maximum likelihood estimates for time-varying and time-invari- ant covariates in the longitudinal case and covariates which vary at the level of the individual and at the cluster level for multilevel problems. A similar number of individuals within clusters or number of measurement occasions within individuals is not required. Empirical Bayesian estimates of per- son-specific trends or cluster-specific effects are provided. Models are illustrated with data from -

Lecture 9: Logit/Probit Prof

Lecture 9: Logit/Probit Prof. Sharyn O’Halloran Sustainable Development U9611 Econometrics II Review of Linear Estimation So far, we know how to handle linear estimation models of the type: Y = β0 + β1*X1 + β2*X2 + … + ε ≡ Xβ+ ε Sometimes we had to transform or add variables to get the equation to be linear: Taking logs of Y and/or the X’s Adding squared terms Adding interactions Then we can run our estimation, do model checking, visualize results, etc. Nonlinear Estimation In all these models Y, the dependent variable, was continuous. Independent variables could be dichotomous (dummy variables), but not the dependent var. This week we’ll start our exploration of non- linear estimation with dichotomous Y vars. These arise in many social science problems Legislator Votes: Aye/Nay Regime Type: Autocratic/Democratic Involved in an Armed Conflict: Yes/No Link Functions Before plunging in, let’s introduce the concept of a link function This is a function linking the actual Y to the estimated Y in an econometric model We have one example of this already: logs Start with Y = Xβ+ ε Then change to log(Y) ≡ Y′ = Xβ+ ε Run this like a regular OLS equation Then you have to “back out” the results Link Functions Before plunging in, let’s introduce the concept of a link function This is a function linking the actual Y to the estimated Y in an econometric model We have one example of this already: logs Start with Y = Xβ+ ε Different β’s here Then change to log(Y) ≡ Y′ = Xβ + ε Run this like a regular OLS equation Then you have to “back out” the results Link Functions If the coefficient on some particular X is β, then a 1 unit ∆X Æ β⋅∆(Y′) = β⋅∆[log(Y))] = eβ ⋅∆(Y) Since for small values of β, eβ ≈ 1+β , this is almost the same as saying a β% increase in Y (This is why you should use natural log transformations rather than base-10 logs) In general, a link function is some F(⋅) s.t. -

Generalized Linear Models

CHAPTER 6 Generalized linear models 6.1 Introduction Generalized linear modeling is a framework for statistical analysis that includes linear and logistic regression as special cases. Linear regression directly predicts continuous data y from a linear predictor Xβ = β0 + X1β1 + + Xkβk.Logistic regression predicts Pr(y =1)forbinarydatafromalinearpredictorwithaninverse-··· logit transformation. A generalized linear model involves: 1. A data vector y =(y1,...,yn) 2. Predictors X and coefficients β,formingalinearpredictorXβ 1 3. A link function g,yieldingavectoroftransformeddataˆy = g− (Xβ)thatare used to model the data 4. A data distribution, p(y yˆ) | 5. Possibly other parameters, such as variances, overdispersions, and cutpoints, involved in the predictors, link function, and data distribution. The options in a generalized linear model are the transformation g and the data distribution p. In linear regression,thetransformationistheidentity(thatis,g(u) u)and • the data distribution is normal, with standard deviation σ estimated from≡ data. 1 1 In logistic regression,thetransformationistheinverse-logit,g− (u)=logit− (u) • (see Figure 5.2a on page 80) and the data distribution is defined by the proba- bility for binary data: Pr(y =1)=y ˆ. This chapter discusses several other classes of generalized linear model, which we list here for convenience: The Poisson model (Section 6.2) is used for count data; that is, where each • data point yi can equal 0, 1, 2, ....Theusualtransformationg used here is the logarithmic, so that g(u)=exp(u)transformsacontinuouslinearpredictorXiβ to a positivey ˆi.ThedatadistributionisPoisson. It is usually a good idea to add a parameter to this model to capture overdis- persion,thatis,variationinthedatabeyondwhatwouldbepredictedfromthe Poisson distribution alone. -

Week 12: Linear Probability Models, Logistic and Probit

Week 12: Linear Probability Models, Logistic and Probit Marcelo Coca Perraillon University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus Health Services Research Methods I HSMP 7607 2019 These slides are part of a forthcoming book to be published by Cambridge University Press. For more information, go to perraillon.com/PLH. c This material is copyrighted. Please see the entire copyright notice on the book's website. Updated notes are here: https://clas.ucdenver.edu/marcelo-perraillon/ teaching/health-services-research-methods-i-hsmp-7607 1 Outline Modeling 1/0 outcomes The \wrong" but super useful model: Linear Probability Model Deriving logistic regression Probit regression as an alternative 2 Binary outcomes Binary outcomes are everywhere: whether a person died or not, broke a hip, has hypertension or diabetes, etc We typically want to understand what is the probability of the binary outcome given explanatory variables It's exactly the same type of models we have seen during the semester, the difference is that we have been modeling the conditional expectation given covariates: E[Y jX ] = β0 + β1X1 + ··· + βpXp Now, we want to model the probability given covariates: P(Y = 1jX ) = f (β0 + β1X1 + ··· + βpXp) Note the function f() in there 3 Linear Probability Models We could actually use our vanilla linear model to do so If Y is an indicator or dummy variable, then E[Y jX ] is the proportion of 1s given X , which we interpret as the probability of Y given X The parameters are changes/effects/differences in the probability of Y by a unit change in X or for a small change in X If an indicator variable, then change from 0 to 1 For example, if we model diedi = β0 + β1agei + i , we could interpret β1 as the change in the probability of death for an additional year of age 4 Linear Probability Models The problem is that we know that this model is not entirely correct. -

Probit Model 1 Probit Model

Probit model 1 Probit model In statistics, a probit model is a type of regression where the dependent variable can only take two values, for example married or not married. The name is from probability + unit.[1] A probit model is a popular specification for an ordinal[2] or a binary response model that employs a probit link function. This model is most often estimated using standard maximum likelihood procedure, such an estimation being called a probit regression. Probit models were introduced by Chester Bliss in 1934, and a fast method for computing maximum likelihood estimates for them was proposed by Ronald Fisher in an appendix to Bliss 1935. Introduction Suppose response variable Y is binary, that is it can have only two possible outcomes which we will denote as 1 and 0. For example Y may represent presence/absence of a certain condition, success/failure of some device, answer yes/no on a survey, etc. We also have a vector of regressors X, which are assumed to influence the outcome Y. Specifically, we assume that the model takes form where Pr denotes probability, and Φ is the Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF) of the standard normal distribution. The parameters β are typically estimated by maximum likelihood. It is also possible to motivate the probit model as a latent variable model. Suppose there exists an auxiliary random variable where ε ~ N(0, 1). Then Y can be viewed as an indicator for whether this latent variable is positive: The use of the standard normal distribution causes no loss of generality compared with using an arbitrary mean and standard deviation because adding a fixed amount to the mean can be compensated by subtracting the same amount from the intercept, and multiplying the standard deviation by a fixed amount can be compensated by multiplying the weights by the same amount. -

9. Logit and Probit Models for Dichotomous Data

Sociology 740 John Fox Lecture Notes 9. Logit and Probit Models For Dichotomous Data Copyright © 2014 by John Fox Logit and Probit Models for Dichotomous Responses 1 1. Goals: I To show how models similar to linear models can be developed for qualitative response variables. I To introduce logit and probit models for dichotomous response variables. c 2014 by John Fox Sociology 740 ° Logit and Probit Models for Dichotomous Responses 2 2. An Example of Dichotomous Data I To understand why logit and probit models for qualitative data are required, let us begin by examining a representative problem, attempting to apply linear regression to it: In September of 1988, 15 years after the coup of 1973, the people • of Chile voted in a plebiscite to decide the future of the military government. A ‘yes’ vote would represent eight more years of military rule; a ‘no’ vote would return the country to civilian government. The no side won the plebiscite, by a clear if not overwhelming margin. Six months before the plebiscite, FLACSO/Chile conducted a national • survey of 2,700 randomly selected Chilean voters. – Of these individuals, 868 said that they were planning to vote yes, and 889 said that they were planning to vote no. – Of the remainder, 558 said that they were undecided, 187 said that they planned to abstain, and 168 did not answer the question. c 2014 by John Fox Sociology 740 ° Logit and Probit Models for Dichotomous Responses 3 – I will look only at those who expressed a preference. Figure 1 plots voting intention against a measure of support for the • status quo. -

A Probit Regression Approach

2016 Annual Evaluation Review, Linked Document D 1 Analyzing the Determinants of Project Success: A Probit Regression Approach 1. This regression analysis aims to ascertain the factors that determine development project outcome. It is intended to complement the trend analysis in the performance of ADB-financed operations from IED’s project evaluations and validations. Given the binary nature of the project outcome (i.e., successful/unsuccessful), a discrete choice probit model is appropriate to empirically test the relationship between project outcome and a set of project and country-level characteristics. 2. In the probit model, a project rated (Y) successful is given a value 1 while a project rated unsuccessful is given a value of 0. Successful projects are those rated successful or highly successful. 1 The probability 푝푖 of having a successful rating over an unsuccessful rating can be expressed as: 푥 ′훽 2 푝 = 푃푟표푏 (푌 = 1|푿) = 푖 (2휋)−1/2exp (−푡 ) 푑푡 = Φ(풙 ′훽) 푖 푖 ∫−∞ 2 푖 where Φ is the cumulative distribution function of a standard normal variable which ensures 0≤ 푝푖 ≤ 1, 풙 is a vector of factors that determine or explain the variation in project outcome and 훽 is a vector of parameters or coefficients that reflects the effect of changes in 풙 on the probability of success. The relationship between a specific factor and the outcome of the probability is interpreted by the means of the marginal effect which accounts for the partial change in the probability.2 The marginal effects provide insights into how the explanatory variables change the predicted probability of project success. -

The Probit & Logit Models Outline

The Random Utility Model The Probit & Logit Models Estimation & Inference Probit & Logit Estimation in Stata Summary Notes The Probit & Logit Models Econometrics II Ricardo Mora Department of Economics Universidad Carlos III de Madrid Máster Universitario en Desarrollo y Crecimiento Económico Ricardo Mora The Probit Model The Random Utility Model The Probit & Logit Models Estimation & Inference Probit & Logit Estimation in Stata Summary Notes Outline 1 The Random Utility Model 2 The Probit & Logit Models 3 Estimation & Inference 4 Probit & Logit Estimation in Stata Ricardo Mora The Probit Model The Random Utility Model The Probit & Logit Models Estimation & Inference Probit & Logit Estimation in Stata Summary Notes Choosing Among a few Alternatives Set up: An agent chooses among several alternatives: labor economics: participation, union membership, ... demographics: marriage, divorce, # of children,... industrial organization: plant building, new product,... regional economics: means of transport,.... We are going to model a choice of two alternatives (not dicult to generalize...) The value of each alternative depends on many factors U0 = b0x0 + e0 U1 = b1x1 + e1 e0;e1 are eects on utility on factors UNOBSERVED TO ECONOMETRICIAN Ricardo Mora The Probit Model The Random Utility Model The Probit & Logit Models Estimation & Inference Probit & Logit Estimation in Stata Summary Notes Choosing Among a few Alternatives Set up: An agent chooses among several alternatives: labor economics: participation, union membership, ... demographics: marriage, -

Simulating Generalized Linear Models

6 Simulating Generalized Linear Models 6.1 INTRODUCTION In the previous chapter, we dug much deeper into simulations, choosing to focus on the standard linear model for all the reasons we discussed. However, most social scientists study processes that do not conform to the assumptions of OLS. Thus, most social scientists must use a wide array of other models in their research. Still, they could benefit greatly from conducting simulations with them. In this chapter, we discuss several models that are extensions of the linear model called generalized linear models (GLMs). We focus on how to simulate their DGPs and evaluate the performance of estimators designed to recover those DGPs. Specifically, we examine binary, ordered, unordered, count, and duration GLMs. These models are not quite as straightforward as OLS because the depen- dent variables are not continuous and unbounded. As we show below, this means we need to use a slightly different strategy to combine our systematic and sto- chastic components when simulating the data. None of these examples are meant to be complete accounts of the models; readers should have some familiarity beforehand.1 After showing several GLM examples, we close this chapter with a brief discus- sion of general computational issues that arise when conducting simulations. You will find that several of the simulations we illustrate in this chapter take much longer to run than did those from the previous chapter. As the DGPs get more demanding to simulate, the statistical estimators become more computationally demanding, and the simulation studies we want to conduct increase in complexity, we can quickly find ourselves doing projects that require additional resources. -

Lecture Notes 7

ECON 497: Lecture Notes 13 Page 1 of 1 Metropolitan State University ECON 497: Research and Forecasting Lecture Notes 13 Dummy Dependent Variable Techniques Studenmund Chapter 13 Basically, if you have a dummy dependent variable you will be estimating a probability. Probabilities are necessarily restricted to fall in the range [0,1] and this puts special conditions on the regression. Just doing a linear regression can result in estimated probabilities that are either negative or greater than 1 and are a bit nonsensical. As a result, there are other techniques for estimating these relationships that can generate better results. The Linear Probability Model The second or third best way to estimate models with dummy dependent variables is to simply estimate the model as you normally might: Di = β0 + β1X1i + β2X2i + εi For example, if you have a sample of the U.S. adult population and you're trying to determine the probability that a person is incarcerated, you might estimate the equation: Di = β0 + β1AGEi + β2GENDERi + εi where Di is a dummy variable taking the value 1 if a person is incarcerated and 0 if not AGEi is the person's age GENDERi is a dummy variable equal to 1 if the person is male and 0 otherwise Imagine that the estimated coefficients are: ˆ Di = 0.0043 - 0.0001*AGEi + 0.0052*GENDERi Interpretation of the estimated coefficients is straightforward. If there are two women, one of whom is one year older than the other, the estimated probability that the older one will be incarcerated will be 0.0001 less than the estimated probability that the younger one will be.