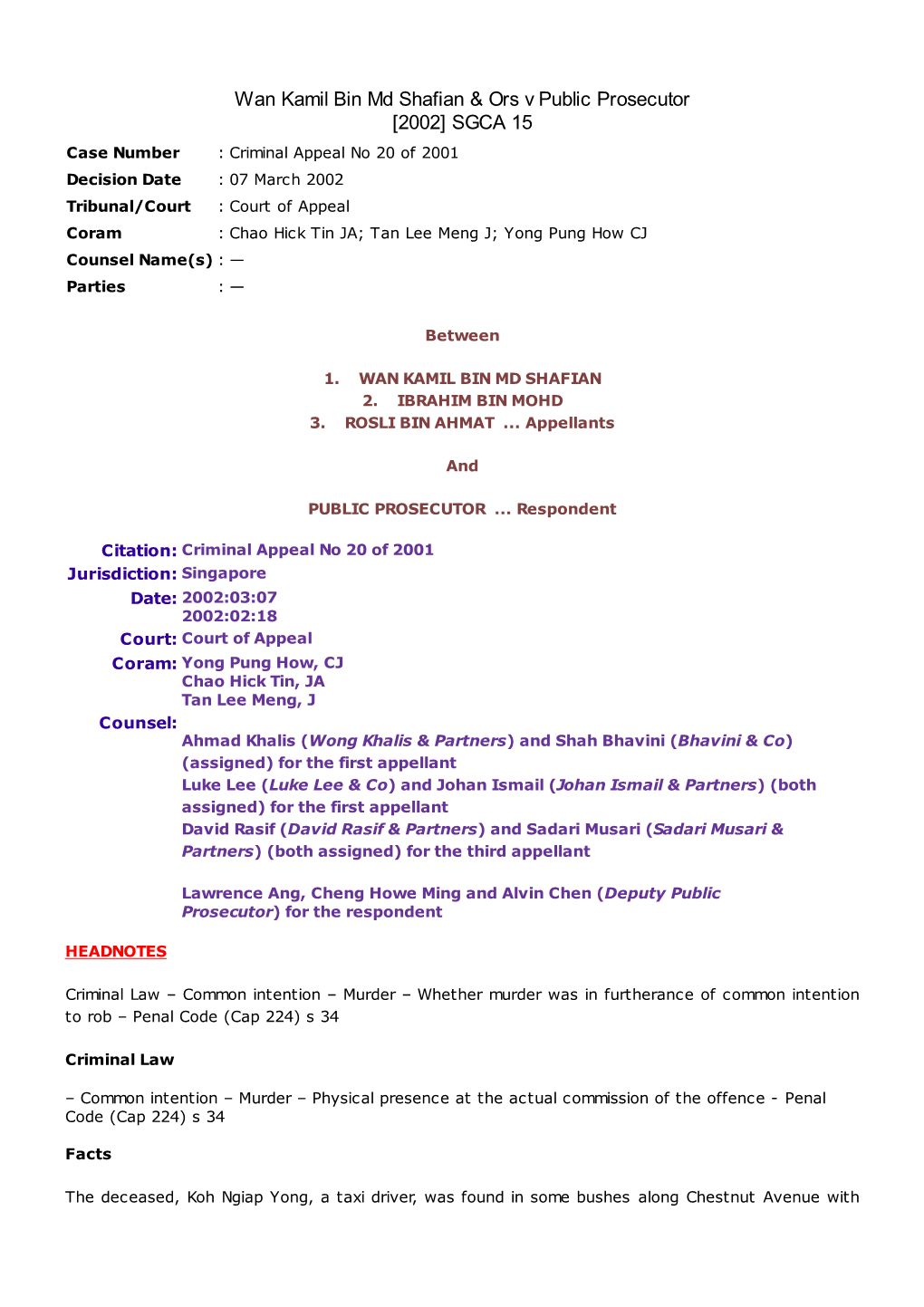

Wan Kamil Bin Md Shafian & Ors V Public Prosecutor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Prosecutor V Wan Kamil Bin Md Shafian and Others

Public Prosecutor v Wan Kamil bin Md Shafian and Others [2001] SGHC 357 Case Number : CC 31/2001 Decision Date : 28 November 2001 Tribunal/Court : High Court Coram : MPH Rubin J Counsel Name(s) : Lawrence Ang, Toh Yung Cheong and April Phang (Deputy Public Prosecutors) for the prosecution; Ahmad Khalis (Wong Khalis & Partners) and Shah Bhavini (Bhabini & Co) (AC) (both assigned) for the first accused; Luke Lee (Luke Lee & Co) and Johan Ismail (Johan Ismail & Partners) (AC) (both assigned) for the second accused; David Rasif (David Rasif & Partners) and Sadari Musari (Sadari Musari & Partners) (AC) (both assigned) for the third acccused Parties : Public Prosecutor — Wan Kamil bin Md Shafian; Ibrahim bin Mohd; Rosli bin Ahmat Judgment GROUNDS OF DECISION 1 Wan Kamil Bin Md Shafian (‘the first accused’) born on 1 May 1967, Ibrahim Bin Mohd (‘the second accused’) born on 18 November 1965 and Rosli Bin Ahmat (‘the third accused’) born on 20 July 1970, all three from Singapore, were jointly charged and tried before me for an offence of murder. The charge against them was that on or about 8 August 2000 at about 11.45am, in furtherance of the common intention of all, they committed murder by causing the death of a 42-year-old taxi driver by name Koh Ngiap Yong, along Chestnut Avenue, Singapore, an offence punishable under s 302 read with s 34 of the Penal Code (Cap 224). 2 The prosecution evidence was that on 8 August 2000 at about 6.10am, the victim left home, first to take his daughter to school and later to drive his taxi-cab bearing registration No SHB 540C for hire. -

Sunny Ang, Mimi Wong, Adrian Lim and John Martin Scripps Are Some

BIBLIOASIA JUL – SEP 2017 Vol. 13 / Issue 02 / Feature violence generally suffer from what is known ings, revenge, jealousy, fear, desperation or Sunny Ang Soo Suan came from a middle- as a pathological personality condition. religious fanaticism. class family and obtained his Senior Criminal or offender profiling (also Singapore has seen several promi- Cambridge Grade One school certificate in known as criminal investigative analy- nent murder cases over the last 50 years, 1955. He received a Colombo Plan scholar- sis) is sometimes used by the police to each unique in its own way. As there are ship in 1957 to train as a commercial airline explain the behavioural makeup of the too many cases to profile within the scope pilot, but was subsequently dropped from perpetrator and identify likely suspects. of this article, we have selected only four the programme due to his arrogant and Careful study of the crime scene photos, cases – Mimi Wong, John Martin Scripps, irresponsible behaviour. Ang also had a the physical and non-physical evidence, Sunny Ang and Adrian Lim – that span the history of theft, and was caught trying to the manner in which the victim was killed decades from the 1960s to 1990s. The first steal from a radio shop on 12 July 1962, or the body disposed of, witnesses’ state- two have been categorised as “crimes of only to be successfully defended by the ments, autopsy photos and forensic lab impulse” (also called “crimes of passion”, prominent criminal lawyer, David Mar- reports allow investigators to compile a usually driven by jealousy or murderous shall, and placed on probation. -

Daniel Vijay S/O Katherasan and Others V Public Prosecutor

Daniel Vijay s/o Katherasan and others v Public Prosecutor [2010] SGCA 33 Case Number : Criminal Appeal No 1 of 2008 Decision Date : 03 September 2010 Tribunal/Court : Court of Appeal Coram : Chan Sek Keong CJ; V K Rajah JA; Choo Han Teck J Counsel Name(s) : James Bahadur Masih (James Masih & Co) and Amarick Singh Gill (Amarick Gill & Co) for the first appellant; Subhas Anandan and Sunil Sudheesan (KhattarWong) for the second appellant; Mohamed Muzammil bin Mohamed (Muzammil & Co) and Allagarsamy s/o Palaniyappan (Allagarsamy & Co) for the third appellant; S Jennifer Marie, David Khoo, Ng Yong Kiat Francis and Ong Luan Tze (Attorney- General's Chambers) for the respondent. Parties : Daniel Vijay s/o Katherasan and others — Public Prosecutor Criminal Law Criminal Procedure and Sentencing [LawNet Editorial Note: This was an appeal from the decision of the High Court in [2008] SGHC 120.] 3 September 2010 Judgment reserved. Chan Sek Keong CJ (delivering the judgment of the court): Introduction 1 This is an appeal by the first appellant, Daniel Vijay s/o Katherasan (“Daniel”), and the second appellant, Christopher Samson s/o Anpalagan (“Christopher”), against the decision of the trial judge (“the Judge”) convicting them of murder in Criminal Case No 16 of 2007 (see Public Prosecutor v Daniel Vijay s/o Katherasan and others [2008] SGHC 120 (“the GD”)). The third appellant, Nakamuthu Balakrishnan (alias Bala) (“Bala”), originally appealed as well against his conviction for murder, but subsequently decided not to proceed with his appeal (see [46]–[47] below). For convenience, we shall hereafter refer to the three appellants collectively as “the Appellants”. -

![Yunani Bin Abdul Hamid V Public Prosecutor [2008]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3779/yunani-bin-abdul-hamid-v-public-prosecutor-2008-3843779.webp)

Yunani Bin Abdul Hamid V Public Prosecutor [2008]

Yunani bin Abdul Hamid v Public Prosecutor [2008] SGHC 58 Case Number : Cr Rev 5/2008 Decision Date : 11 April 2008 Tribunal/Court : High Court Coram : V K Rajah JA Counsel Name(s) : Abraham S Vergis and Darrell Low Kim Boon (Drew & Napier LLC) for the applicant; Lawrence Ang Boon Kong, Lau Wing Yum and Christopher Ong Siu Jin (Attorney-General's Chambers) for the respondent Parties : Yunani bin Abdul Hamid — Public Prosecutor Courts and Jurisdiction – High court – Exercise of revisionary powers – Exercise of revisionary powers where there is a plea of guilty – Section 23 Supreme Court of Judicature Act (Cap 322, 2007 Rev Ed) – Sections 266, 267, 268, 269, 270 Criminal Procedure Code (Cap 68, 1985 Rev Ed) Criminal Procedure and Sentencing – Revision of proceedings – Appropriate course of action after exercise of revisionary powers – Whether matter should be remitted back for trial or stayed – Section 23 Supreme Court of Judicature Act (Cap 322, 2007 Rev Ed) – Sections 266, 267, 268, 269, 270 Criminal Procedure Code (Cap 68, 1985 Rev Ed) Criminal Procedure and Sentencing – Revision of proceedings – Exercise of revisionary powers – Exercise of revisionary powers where there is a plea of guilty – Whether there was serious injustice which would warrant exercise of revisionary power – Presence of serious injustice if pressures faced by accused to plead guilty are such that accused did not genuinely have freedom to choose between pleading guilty and pleading not guilty – Presence of serious injustice if additional evidence before reviewing court casting serious doubts as to guilt of accused – Section 23 Supreme Court of Judicature Act (Cap 322, 2007 Rev Ed) – Sections 266, 267, 268, 269, 270 Criminal Procedure Code (Cap 68, 1985 Rev Ed) 11 April 2008 Judgment reserved. -

Combating Corruption in Singapore

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: https://www.emerald.com/insight/1727-2645.htm Two Combating corruption in corruption Singapore: a comparative analysis scandals in of two scandals Singapore Jon S.T. Quah 87 Anti-Corruption Consultant, Singapore Received 6 November 2019 Revised 8 January 2020 Abstract Accepted 27 February 2020 Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to compare two corruption scandals in Singapore to illustrate how its government has dealt with these scandals and to discuss the implications for its anti-corruption strategy. Design/methodology/approach – This paper analyses the Teh Cheang Wan and Edwin Yeo scandals by relying on published official and press reports. Findings – Both scandals resulted in adverse consequences for the offenders. Teh committed suicide on 14 December 1986 before he could be prosecuted for his bribery offences. Yeo was found guilty of criminal breach of trust and forgery and sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment. The Commission of Inquiry found that the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB) was thorough in its investigations which confirmed that only Teh and no other minister or public official were implicated in the bribery offences. The Independent Review Panel appointed by the Prime Minister’s Office to review the CPIB’s internal controls following Yeo’s offences recommended improvements to strengthen the CPIB’s financial procedures and audit system. Singapore has succeeded in minimising corruption because its government did not cover-up the scandals but punished the guilty offenders and introduced measures to prevent their recurrence. Originality/value – This paper will be useful for scholars, policymakers and anti-corruption practitioners interested in Singapore’s anti-corruption strategy and how its government handles corruption scandals. -

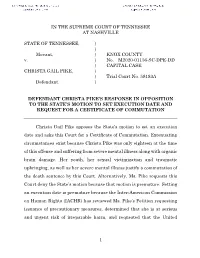

Response to Motion

Electronically RECEIVED on June 07, 2021 Electronically FILED on June 07, 2021 Appellate Court Clerk Appellate Court Clerk IN THE SUPREME COURT OF TENNESSEE AT NASHVILLE STATE OF TENNESSEE, ) ) Movant, ) KNOX COUNTY v. ) No. M2020-01156-SC-DPE-DD ) CAPITAL CASE CHRISTA GAIL PIKE, ) ) Trial Court No. 58183A Defendant. ) DEFENDANT CHRISTA PIKE’S RESPONSE IN OPPOSITION TO THE STATE’S MOTION TO SET EXECUTION DATE AND REQUEST FOR A CERTIFICATE OF COMMUTATION Christa Gail Pike opposes the State’s motion to set an execution date and asks this Court for a Certificate of Commutation. Extenuating circumstances exist because Christa Pike was only eighteen at the time of this offense and suffering from severe mental illness along with organic brain damage. Her youth, her sexual victimization and traumatic upbringing, as well as her severe mental illness justify a commutation of the death sentence by this Court. Alternatively, Ms. Pike requests this Court deny the State’s motion because that motion is premature. Setting an execution date is premature because the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) has reviewed Ms. Pike’s Petition requesting issuance of precautionary measures, determined that she is at serious and urgent risk of irreparable harm, and requested that the United 1 States refrain from carrying out the death penalty on Christa Pike until the IACHR can complete its investigation. Furthermore, setting an execution date at this time is also premature because TDOC safety measures in response to the COVID pandemic have precluded completing a current mental health evaluation. The State has just begun reopening and prisons have only recently begun allowing experts to conduct in-person evaluations. -

Singapore Shipping Association ANNUAL REVIEW 2011/12 Towards a Brighter Future

Singapore Shipping Association ANNUAL REVIEW 2011/12 Towards a Brighter Future Contents SINGAPORE SHIPPING ASSOCIATION 03 President’s Report 59 Tras Street Singapore 078998 06 Council Members 2011/2013 Telephone: (65) 6222 5238 Facsimile: (65) 6222 5527 Email: [email protected] 07 Organisational Structure Website: www.ssa.org.sg 08 SSA Committees 2011/2013 Activities Report 39 Port and Shipping Statistics 40 Membership Summary 46 Membership Particulars & Fleet Statistics • Fleet Statistics Summary • Ordinary Members • Associate Members Special thanks to our statistics contributors, advertisers, and the following companies for granting us the permission to use their photographs: AET Tankers Pte Ltd, BW Maritime Pte Ltd, EU NAVFOR, Hong Lam Marine Pte Ltd, Jurong Port Pte Ltd, Masterbulk Pte Ltd, NYK Bulkship (Asia) Pte. Ltd., PACC Offshore Services Holdings Pte Ltd, PSA Corporation Limited, Rickmers Trust Management Pte Ltd, Singapore Tourism Board, Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, Swire Pacific Offshore Operations (Pte) Ltd. This publication is published by the Singapore Shipping Association. No contents may be reproduced in part or in whole without the prior consent of the publisher. MICA (P) 043/07/2012 SSA The Mission President’s Statement Report Mr. Patrick Phoon, President, Singapore Shipping Association As an Association 2011 has been a very difficult year for the shipping 2012 as long-overdue, but a step in the right direction. industry. The second half of 2011 saw a slight recovery in The effort must be sustained, however! Furthermore, The Association will protect and promote the interests of the shipping market but this was short-lived. Soaring oil any effective strategy must also address the root causes its members. -

Grounds of Decision

IN THE HIGH COURT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE [2019] SGHC 205 Originating Summons No 14 of 2018 Between Singapore Medical Council … Applicant And BXR … Respondent GROUNDS OF DECISION [Professions] — [Medical profession and practice] — [Professional conduct] [Civil Procedure] — [Costs] — [Principles] TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION............................................................................................1 BACKGROUND FACTS ................................................................................2 THE DECISION OF THE DT ........................................................................5 THE DT’S FINDINGS ON CONVICTION ..............................................................5 THE DT’S DECISION ON COSTS ........................................................................7 THE PARTIES’ CASES..................................................................................7 THE APPLICABLE LAW ..............................................................................8 THE POWER OF THE HIGH COURT TO ORDER COSTS AGAINST THE SMC..........8 THE PRINCIPLES TO BE APPLIED IN DETERMINING WHETHER TO MAKE AN ADVERSE COSTS ORDER AGAINST THE SMC....................................................9 PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS............................................................10 OUR DECISION ............................................................................................12 THE RESPONDENT WAS ACQUITTED OF THE CHARGES ...................................12 THE CHARGES WERE NOT BROUGHT ON GROUNDS THAT -

Folio No: DM.316 Folio Title: Criminal Precedence Content Description

Folio No: DM.316 Folio Title: Criminal Precedence Content Description: This file contains 65 items most of which are Petitions of Appeals in Criminal Cases ITEM DOCUMENT DIGITIZATION ACCESS DOCUMENT CONTENT NO DATE STATUS STATUS Statement of case re: Mr. Kyle-Little. The prosecution DM.316.001 18/9/1969 had filed criminal charges under Section 4(c) of the Digitized Open Prevention of Corruption Act. Supplemental Petition of Appeal re: Criminal Appeal No. DM.316.002 1965 Digitized Open 2 of 1965. Supplemental Petition of Appeal re: Criminal District DM.316.003 Undated Digitized Open Court Case No. 151 of 1964. Supplemental Petition of Appeal re: Criminal District DM.316.004 28/2/1966 Digitized Open Court Case No. 257 of 1964. Supplemental Petition of Appeal re: Criminal Appeal No. DM.316.005 31/10/1966 Digitized Open X 31 of 1966. Supplemental Petition of Appeal re: High Court Criminal DM.316.006 Undated Digitized Open Case No. 7 of 1966. Supplemental Petition of Appeal re: Criminal Appeal No. DM.316.007 Undated Digitized Open Y.6 of 1966. Petition of Appeal re: High Court Criminal Case No. 17 DM.316.008 5/5/1969 Digitized Open of 1968. DM.316.009 16/12/1966 Re: DM.316.006. Digitized Open DM.316.010 19/12/1969 Petition of Appeal re: Criminal Appeal No. Y. 17 of 1969. Digitized Open DM.316.011 1966 Petition of Appeal re: Criminal Appeal No. X41 of 1966. Digitized Open Draft Petition of Appeal re: Criminal Appeal No. 29 of DM.316.012 1971 Digitized Open 1970. -

Tentative List of Accepted Events for #AWP20

#AWP20 Accepted Events 2020 AWP Conference & Bookfair March 4 -7, 2020, San Antonio, Texas Henry B. González Convention Center Tentative List of Accepted Events for #AWP20 This list of accepted events for the 2020 Conference & Bookfair is tentative as we wait to receive confirmation from all event organizers and participants. We are also working to ensure that each participant does not participate in more than two events. The final conference schedule will be posted in October at awpwriter.org. The list is organized by event type: panel discussions (pg. 2), pedagogy events (pg. 76), and readings (pg. 87). Within these categories, events are alphabetized by title. Event titles and descriptions have not been edited for grammar or content. AWP believes in freedom of expression and open debate, and the views and opinions expressed in these event titles and descriptions may not necessarily reflect the views of AWP’s staff, board of trustees, or members. Visit the page on How Events Are Selected for details about how the 2020 San Antonio Subcommittee made their selections. AWP’s conference subcommittee worked hard to shape a diverse schedule for #AWP20, creating the best possible balance among genres, presenters, and topics. Every year, there are a number of high-quality events that have to be left off the schedule due to space limitations. Although the pool of submissions was highly competitive, we did our best to ensure that the conference belongs to AWP’s numerous and varied constituencies. From 1,359, we tentatively accepted 480 events involving more than 2,000 panelists. For more information about events relating to particular affinity groups, please see the Community Events of #AWP20. -

Raising the Bar for the Mens Rea Requirement in Common Intention Cases Eunice CHUA Singapore Management University, [email protected]

Singapore Management University Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University Research Collection School Of Law School of Law 1-2011 Raising the Bar for the Mens Rea Requirement in Common Intention Cases Eunice CHUA Singapore Management University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/sol_research Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Law Enforcement and Corrections Commons Citation CHUA, Eunice. Raising the Bar for the Mens Rea Requirement in Common Intention Cases. (2011). Singapore Law Review. 29, 21-34. Research Collection School Of Law. Available at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/sol_research/1767 This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Collection School Of Law by an authorized administrator of Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University. For more information, please email [email protected]. Published in Singapore Law Review, 2011, vol. 29, pp. 21-34. Singapore Law Review (2011) 29 SingL Re, RAISING THE BAR FOR THE MENS REA REQUIREMENT IN COMMON INTENTION CASES Daniel Vjay s/o Katherasan v. Public Prosecutor [2010] 4 Sing. L.R. 1119 CHUA Hui HAN, EUNICE* Recently, the Court of,4ppeal in Daniel Vijay s/o Katherasan v. Public Prosecutor took the view that the law on common intention was not adequatelysettled in Singaporedespite the 138-year history of s. 34 ofthe Penal Code. It went on to give an extensive review ofthe cases interpretingthe section as well as its Indian equivalent,before settingout the properapproach to take in "twin crime" common intention cases,focusing specifically on the mens rea element requiredin orderto establish construc- tive liabilityforthe secondary crime. -

Opening of the Legal Year 2009

2 January 2009 OPENING OF THE LEGAL YEAR 2009 May it please your honours, Chief Justice, Judges of Appeal and Judges of the Supreme Court. 1 2008 has been a year of great change for the Legal Service. We have seen the departure in quick succession of so many senior and respected colleagues: starting with the Attorney-General himself, Mr Justice Chao Hick Tin, followed in short order by Mr Ter Kim Cheu (our long-time legislative draughtsman), Mr Lawrence Ang (a pillar of the prosecution for almost 30 years) and Mr Sivakant Tiwari (whose invaluable international law expertise has been relied upon repeatedly to protect Singapore’s interests in international forums). I would like to pay tribute to these men, who have dedicated their entire professional lives to the Legal Service. We are grateful for their great contributions to the work of the Attorney-General’s Chambers. 2. If I may be permitted to inject a personal note, I was privileged to serve with Mr Justice Chao Hick Tin, then Attorney-General, and Mr Justice Chan Seng Onn, then Solicitor-General, when I first joined the Attorney-General's Chambers. I would like to express my deep appreciation to them for their support and guidance. 3. We now have five new Principal Senior State Counsel in the Attorney-General’s Chambers: Mr Charles Lim of the Legislation and Law Reform Division; Mr David Chong of the Civil Division; Ms Jennifer Marie of the Criminal Justice Division; Mr Bala Reddy of the State Prosecution Division; and Mr Lionel Yee of the International Affairs Division.