Download=351:Wajir-County-Integrated- Development-Plan-2018–2022)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

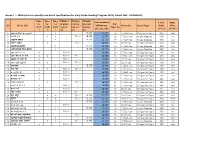

Code Under Name Girls Boys Total Girls Boys Total 010290001

P|D|LL|S G8 G10 Code Under Name Girls Boys Total Girls Boys Total 010290001 Maiwakhola Gaunpalika Patidanda Ma Vi 15 22 37 25 17 42 010360002 Meringden Gaunpalika Singha Devi Adharbhut Vidyalaya 8 2 10 0 0 0 010370001 Mikwakhola Gaunpalika Sanwa Ma V 27 26 53 50 19 69 010160009 Phaktanglung Rural Municipality Saraswati Chyaribook Ma V 28 10 38 33 22 55 010060001 Phungling Nagarpalika Siddhakali Ma V 11 14 25 23 8 31 010320004 Phungling Nagarpalika Bhanu Jana Ma V 88 77 165 120 130 250 010320012 Phungling Nagarpalika Birendra Ma V 19 18 37 18 30 48 010020003 Sidingba Gaunpalika Angepa Adharbhut Vidyalaya 5 6 11 0 0 0 030410009 Deumai Nagarpalika Janta Adharbhut Vidyalaya 19 13 32 0 0 0 030100003 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Janaki Ma V 13 5 18 23 9 32 030230002 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Singhadevi Adharbhut Vidyalaya 7 7 14 0 0 0 030230004 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Jalpa Ma V 17 25 42 25 23 48 030330008 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Khambang Ma V 5 4 9 1 2 3 030030001 Ilam Municipality Amar Secondary School 26 14 40 62 48 110 030030005 Ilam Municipality Barbote Basic School 9 9 18 0 0 0 030030011 Ilam Municipality Shree Saptamai Gurukul Sanskrit Vidyashram Secondary School 0 17 17 1 12 13 030130001 Ilam Municipality Purna Smarak Secondary School 16 15 31 22 20 42 030150001 Ilam Municipality Adarsha Secondary School 50 60 110 57 41 98 030460003 Ilam Municipality Bal Kanya Ma V 30 20 50 23 17 40 030460006 Ilam Municipality Maheshwor Adharbhut Vidyalaya 12 15 27 0 0 0 030070014 Mai Nagarpalika Kankai Ma V 50 44 94 99 67 166 030190004 Maijogmai Gaunpalika -

Website Disclosure Subsidy.Xlsx

Subsidy Loan Details as on Ashad End 2078 S.N Branch Name Province District Address Ward No 1 Butwal SHIVA RADIO & SPARE PARTS Lumbini Rupandehi BUTWAL-06,RUPANDEHI,TRAFFIC CHOWK 6 2 Sandhikharkaka MATA SUPADEURALI MOBILE Lumbini Rupandehi BUTWAL-06,RUPANDEHI 06 3 Butwal N G SQUARE Lumbini Rupandehi BUTWAL-11,KALIKANAGAR 11 4 Butwal ANIL KHANAL Lumbini Rupandehi TILOTTAMA-5,MANIGARAM 5 5 Butwal HIMALAYAN KRISHI T.P.UDH.PVT.LTD Lumbini Rupandehi TILOTTAMA-05,RUPANDEHI,MANIGRAM 5 6 Butwal HIMALAYAN KRISHI T.P.UDH.PVT.LTD Lumbini Rupandehi TILOTTAMA-05,RUPANDEHI,MANIGRAM 5 7 Butwal HIMALAYAN KRISHI T.P.UDH.PVT.LTD Lumbini Rupandehi TILOTTAMA-05,RUPANDEHI,MANIGRAM 5 8 Butwal HARDIK POULTRY FARM Lumbini Kapilbastu BUDDHA BHUMI-02,KAPILBASTU 2 9 Butwal HARDIK POULTRY FARM Lumbini Kapilbastu BUDDHA BHUMI-02,KAPILBASTU 2 10 Butwal HARDIK POULTRY FARM Lumbini Kapilbastu BUDDHA BHUMI-02,KAPILBASTU 2 11 Butwal RAMNAGAR AGRO FARM PVT.LTD Lumbini Nawalparasi SARAWAL-02, NAWALPARASI 2 12 Butwal RAMNAGAR AGRO FARM PVT.LTD Lumbini Nawalparasi SARAWAL-02, NAWALPARASI 2 13 Butwal BUDDHA BHUMI MACHHA PALAN Lumbini Kapilbastu BUDDHI-06,KAPILVASTU 06 14 Butwal TANDAN POULTRY BREEDING FRM PVT.LTD Lumbini Rupandehi BUTWAL-11,RUPANDEHI,KALIKANAGAR 11 15 Butwal COFFEE ROAST HOUSE Lumbini Rupandehi BUTWAL-09,RUPANDEHI 09 16 Butwal NUTRA AGRO INDUSTRY Lumbini Rupandehi BUTWAL 13 BELBAS, POUDEL PATH 13 17 Butwal SHUVA SAMBRIDDHI UNIT.AG.F PVT.LTD. Lumbini Rupandehi SAINAMAINA-1, KASHIPUR,RUPANDEHI 1 18 Butwal SHUVA SAMBRIDDHI UNIT.AG.F PVT.LTD. Lumbini Rupandehi SAINAMAINA-1, KASHIPUR,RUPANDEHI 1 19 Butwal SANGAM HATCHERY & BREEDING FARM Lumbini Rupandehi BUTWAL-09, RUPANDEHI 9 20 Butwal SHREE LAXMI KRISHI TATHA PASUPANCHH Lumbini Palpa TANSEN-14,ARGALI 14 21 Butwal R.C.S. -

Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal

Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal Volumes: Volume I : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 1 Volume II : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 2 Volume III : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 3 Volume IV : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 4 Volume V : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 5 Volume VI : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 6 Volume VII : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 7 Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Department of Forest Research and Survey Kathmandu July 2017 © Department of Forest Research and Survey, 2017 Any reproduction of this publication in full or in part should mention the title and credit DFRS. Citation: DFRS, 2017. Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal. Department of Forest Research and Survey (DFRS). Kathmandu, Nepal Prepared by: Coordinator : Dr. Deepak Kumar Kharal, DG, DFRS Member : Dr. Prem Poudel, Under-secretary, DSCWM Member : Rabindra Maharjan, Under-secretary, DoF Member : Shiva Khanal, Under-secretary, DFRS Member : Raj Kumar Rimal, AFO, DoF Member Secretary : Amul Kumar Acharya, ARO, DFRS Published by: Department of Forest Research and Survey P. O. Box 3339, Babarmahal Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: 977-1-4233510 Fax: 977-1-4220159 Email: [email protected] Web: www.dfrs.gov.np Cover map: Front cover: Map of Forest Cover of Nepal FOREWORD Forest of Nepal has been a long standing key natural resource supporting nation's economy in many ways. Forests resources have significant contribution to ecosystem balance and livelihood of large portion of population in Nepal. Sustainable management of forest resources is essential to support overall development goals. -

The Kamaiya System of Bonded Labour in Nepal

Nepal Case Study on Bonded Labour Final1 1 THE KAMAIYA SYSTEM OF BONDED LABOUR IN NEPAL INTRODUCTION The origin of the kamaiya system of bonded labour can be traced back to a kind of forced labour system that existed during the rule of the Lichhabi dynasty between 100 and 880 AD (Karki 2001:65). The system was re-enforced later during the reign of King Jayasthiti Malla of Kathmandu (1380–1395 AD), the person who legitimated the caste system in Nepali society (BLLF 1989:17; Bista 1991:38-39), when labourers used to be forcibly engaged in work relating to trade with Tibet and other neighbouring countries. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Gorkhali and Rana rulers introduced and institutionalised new forms of forced labour systems such as Jhara,1 Hulak2, Beth3 and Begar4 (Regmi, 1972 reprint 1999:102, cited in Karki, 2001). The later two forms, which centred on agricultural works, soon evolved into such labour relationships where the workers became tied to the landlords being mortgaged in the same manner as land and other property. These workers overtimes became permanently bonded to the masters. The kamaiya system was first noticed by anthropologists in the 1960s (Robertson and Mishra, 1997), but it came to wider public attention only after the change of polity in 1990 due in major part to the work of a few non-government organisations. The 1990s can be credited as the decade of the freedom movement of kamaiyas. Full-scale involvement of NGOs, national as well as local, with some level of support by some political parties, in launching education classes for kamaiyas and organising them into their groups culminated in a kind of national movement in 2000. -

Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Environment Nepal

Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Environment Nepal Forests for Prosperity Project Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) March 8, 2020 Executive Summary 1. This Environment and Social Management Framework (ESMF) has been prepared for the Forests for Prosperity (FFP) Project. The Project is implemented by the Ministry of Forest and Environment and funded by the World Bank as part of the Nepal’s Forest Investment Plan under the Forest Investment Program. The purpose of the Environmental and Social Management Framework is to provide guidance and procedures for screening and identification of expected environmental and social risks and impacts, developing management and monitoring plans to address the risks and to formulate institutional arrangements for managing these environmental and social risks under the project. 2. The Project Development Objective (PDO) is to improve sustainable forest management1; increase benefits from forests and contribute to net Greenhouse Gas Emission (GHG) reductions in selected municipalities in provinces 2 and 5 in Nepal. The short-to medium-term outcomes are expected to increase overall forest productivity and the forest sector’s contribution to Nepal’s economic growth and sustainable development including improved incomes and job creation in rural areas and lead to reduced Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions and increased climate resilience. This will directly benefit the communities, including women and disadvantaged groups participating in Community Based Forest Management (CBFM) as well and small and medium sized entrepreneurs (and their employees) involved in forest product harvesting, sale, transport and processing. Indirect benefits are improved forest cover, environmental services and carbon capture and storage 3. The FFP Project will increase the forest area under sustainable, community-based and productive forest management and under private smallholder plantations (mainly in the Terai), resulting in increased production of wood and non-wood forest products. -

Table of Province 05, Preliminary Results, Nepal Economic Census

Number of Number of Persons Engaged District and Local Unit establishments Total Male Female Rukum East District 1,020 2,753 1,516 1,237 50101PUTHA UTTANGANGA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 276 825 501 324 50102SISNE RURAL MUNICIPALITY 464 1,164 620 544 50103BHOOME RURAL MUNICIPALITY 280 764 395 369 Rolpa District 5,096 15,651 8,518 7,133 50201SUNCHHAHARI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 302 2,231 1,522 709 50202THAWANG RURAL MUNICIPALITY 244 760 362 398 50203PARIWARTAN RURAL MUNICIPALITY 457 980 451 529 50204SUKIDAHA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 408 408 128 280 50205MADI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 407 881 398 483 50206TRIBENI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 372 1,186 511 675 50207ROLPA MUNICIPALITY 1,160 3,441 1,763 1,678 50208RUNTIGADHI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 560 3,254 2,268 986 50209SUBARNABATI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 882 1,882 845 1,037 50210LUNGRI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 304 628 270 358 Pyuthan District 5,632 22,336 12,168 10,168 50301GAUMUKHI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 431 1,716 890 826 50302NAUBAHINI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 621 1,940 1,059 881 50303JHIMARUK RURAL MUNICIPALITY 568 2,424 1,270 1,154 50304PYUTHAN MUNICIPALITY 1,254 4,734 2,634 2,100 50305SWORGADWARI MUNICIPALITY 818 2,674 1,546 1,128 50306MANDAVI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 427 1,538 873 665 50307MALLARANI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 449 2,213 1,166 1,047 50308AAIRAWATI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 553 3,477 1,812 1,665 50309SARUMARANI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 511 1,620 918 702 Gulmi District 9,547 36,173 17,826 18,347 50401KALI GANDAKI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 540 1,133 653 480 50402SATYAWOTI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 689 2,406 1,127 1,279 50403CHANDRAKOT RURAL MUNICIPALITY 756 3,556 1,408 2,148 -

Annex 1 : - Srms Print Run Quantity and Detail Specifications for Early Grade Reading Program 2019 ( Cohort 1&2 : 16 Districts)

Annex 1 : - SRMs print run quantity and detail specifications for Early Grade Reading Program 2019 ( Cohort 1&2 : 16 Districts) Number Number Number Titles Titles Titles Total numbers Cover Inner for for for of print of print of print # of SN Book Title of Print run Book Size Inner Paper Print Print grade grade grade run for run for run for Inner Pg (G1, G2 , G3) (Color) (Color) 1 2 3 G1 G2 G3 1 अनारकल�को अꅍतरकथा x - - 15,775 15,775 24 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 2 अनौठो फल x x - 16,000 15,775 31,775 28 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 3 अमु쥍य उपहार x - - 15,775 15,775 40 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 4 अत� र बु饍�ध x - 16,000 - 16,000 36 21x27 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 5 अ쥍छ�को औषधी x - - 15,775 15,775 36 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 6 असी �दनमा �व�व भ्रमण x - - 15,775 15,775 32 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 7 आउ गन� १ २ ३ x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 8 आज मैले के के जान� x x 16,000 16,000 - 32,000 16 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 9 आ굍नो घर राम्रो घर x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 21x27 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 10 आमा खुसी हुनुभयो x x 16,000 16,000 - 32,000 20 21x27 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 11 उप配यका x - - 15,775 15,775 20 14.8x21 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4X4 12 ऋतु गीत x x 16,000 16,000 - 32,000 16 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 13 क का �क क� x 16,000 - - 16,000 16 14.8x21 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 14 क दे�ख � स륍म x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 2X0 2x2 15 कता�तर छौ ? x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 2X0 2x2 -

Violations in the Name of Conservation “What Crime Had I Committed by Putting My Feet on the Land That I Own?”

VIOLATIONS IN THE NAME OF CONSERVATION “WHAT CRIME HAD I COMMITTED BY PUTTING MY FEET ON THE LAND THAT I OWN?” Amnesty International is a movement of 10 million people which mobilizes the humanity in everyone and campaigns for change so we can all enjoy our human rights. Our vision is of a world where those in power keep their promises, respect international law and are held to account. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and individual donations. We believe that acting in solidarity and compassion with people everywhere can change our societies for the better. © Amnesty International 2021 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Illustration by Colin Foo (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. Photo: Chitwan National Park, Nepal. © Jacek Kadaj via Getty Images https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2021 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 31/4536/2021 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 1.1 PROTECTING ANIMALS, EVICTING PEOPLE 5 1.2 ANCESTRAL HOMELANDS HAVE BECOME NATIONAL PARKS 6 1.3 HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS BY THE NEPAL ARMY 6 1.4 EVICTION IS NOT THE ANSWER 6 1.5 CONSULTATIVE, DURABLE SOLUTIONS ARE A MUST 7 1.6 LIMITED POLITICAL WILL 8 2. -

Nepal Case Study

WWF POPULATION-HEALTH- ENVIRONMENT PROGRAM LEARNING AGENDA Engendering Conservation Constituencies: Understanding the Links between Women’s Empowerment and Biodiversity Conservation Outcomes for PHE Programs WWF- NEPAL CASE STUDY April, 2010 Author: Nancy K. Diamond, Senior Gender Consultant Diamond Consulting ([email protected]) 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page Number 1. Acknowledgements 5 2. Study Background 5 2a. Consultancy Objectives 5 2b. Literature Review 6 2c. Methodology 13 3. Nepal’s Terai Arc Landscape 15 4. TAL PHE Activities 21 5. Findings and Discussion 31 6. Conclusion 52 Annexes: A. Itinerary 56 B. WWESPE Tool 58 C. Interview guides 61 D. Gender Action Plan for the Terai Arc Landscape Program 77 E. Requests from Community Informants 81 3 List of Tables Page Number 1. Scorecard Criteria for the WWESPE Tool 10 2. Comparison of Land Size, Forest Cover, Population Density and Land Holdings 23 for Dang, Kailali and Bardiya Districts 3. Comparison of Population, Caste/Ethnic Composition and Migration Statistics 24 for Dang, Kailali and Bardiya Districts 4. Reproductive Health and Literacy Statistics for Dang, Kailali and Bardiya Districts 25 5. TAL’s PHE and Other Activities in Dang, Kailali and Bardiya 26 6. Differences in Perceptions about Men’s and Women’s Involvement in TAL 31 Activities 7. Number and Percentage of Individual Informants Who Received TAL Goods and 30 Services 8. Women’s Economic Empowerment Changes Attributed to TAL, by District 35 9. Observations about the Extent of TAL’s Economic Empowerment Impacts on 36 Women, by District 10. Women’s Social Empowerment Changes Attributed to TAL, by District 37 11. -

ZSL National Red List of Nepal's Birds Volume 5

The Status of Nepal's Birds: The National Red List Series Volume 5 Published by: The Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, UK Copyright: ©Zoological Society of London and Contributors 2016. All Rights reserved. The use and reproduction of any part of this publication is welcomed for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the source is acknowledged. ISBN: 978-0-900881-75-6 Citation: Inskipp C., Baral H. S., Phuyal S., Bhatt T. R., Khatiwada M., Inskipp, T, Khatiwada A., Gurung S., Singh P. B., Murray L., Poudyal L. and Amin R. (2016) The status of Nepal's Birds: The national red list series. Zoological Society of London, UK. Keywords: Nepal, biodiversity, threatened species, conservation, birds, Red List. Front Cover Back Cover Otus bakkamoena Aceros nipalensis A pair of Collared Scops Owls; owls are A pair of Rufous-necked Hornbills; species highly threatened especially by persecution Hodgson first described for science Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson and sadly now extinct in Nepal. Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of participating organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of any participating organizations. Notes on front and back cover design: The watercolours reproduced on the covers and within this book are taken from the notebooks of Brian Houghton Hodgson (1800-1894). -

Human–Tiger Panthera Tigris Conflict and Its Perception in Bardia National Park, Nepal

Human–tiger Panthera tigris conflict and its perception in Bardia National Park, Nepal B ABU R. BHATTARAI and K LAUS F ISCHER Abstract Human–wildlife conflict is a significant problem Wang & Macdonald, 2006). An increase in the human that often results in retaliatory killing of predators. Such population has resulted in increased incidence of conflict conflict is particularly pronounced between humans and between people and carnivores (Graham et al., 2005; tigers Panthera tigris because of fatal attacks by tigers on Woodroffe et al., 2005a). This often results in retaliatory humans. We investigated the incidence and perception of persecution, which is a significant threat to large carnivores human–tiger conflict in the buffer zone of Bardia National (Mishra et al., 2003; Treves & Karanth, 2003; Nyhus & Park, Nepal, by interviewing 273 local householders and Tilson, 2004). Thus, conservation measures to protect large 27 key persons (e.g. representatives of local communities, carnivores can be controversial and may lack support Park officials). Further information was compiled from from local communities (Graham et al., 2005). the Park’s archives. The annual loss of livestock attributable Large carnivores play a significant role in ecosystem to tigers was 0.26 animals per household, amounting to an functioning, with their absence inducing changes in annual loss of 2% of livestock. Livestock predation rates were predator–prey relationships and inter-specific competition particularly high in areas with low abundance of natural (Treves & Karanth, 2003). Many carnivores serve as prey. During 1994–2007 12 people were killed and a further important umbrella and flagship species, benefiting other four injured in tiger attacks. -

S.N Local Government Bodies EN स्थानीय तहको नाम NP District

S.N Local Government Bodies_EN थानीय तहको नाम_NP District LGB_Type Province Website 1 Fungling Municipality फु ङलिङ नगरपालिका Taplejung Municipality 1 phunglingmun.gov.np 2 Aathrai Triveni Rural Municipality आठराई त्रिवेणी गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 aathraitribenimun.gov.np 3 Sidingwa Rural Municipality लिदिङ्वा गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 sidingbamun.gov.np 4 Faktanglung Rural Municipality फक्ताङिुङ गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 phaktanglungmun.gov.np 5 Mikhwakhola Rural Municipality लि啍वाखोिा गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 mikwakholamun.gov.np 6 Meringden Rural Municipality िेररङिेन गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 meringdenmun.gov.np 7 Maiwakhola Rural Municipality िैवाखोिा गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 maiwakholamun.gov.np 8 Yangworak Rural Municipality याङवरक गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 yangwarakmuntaplejung.gov.np 9 Sirijunga Rural Municipality लिरीजङ्घा गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 sirijanghamun.gov.np 10 Fidhim Municipality दफदिि नगरपालिका Panchthar Municipality 1 phidimmun.gov.np 11 Falelung Rural Municipality फािेिुुंग गाउँपालिका Panchthar Rural municipality 1 phalelungmun.gov.np 12 Falgunanda Rural Municipality फा쥍गुनन्ि गाउँपालिका Panchthar Rural municipality 1 phalgunandamun.gov.np 13 Hilihang Rural Municipality दिलििाङ गाउँपालिका Panchthar Rural municipality 1 hilihangmun.gov.np 14 Kumyayek Rural Municipality कु म्िायक गाउँपालिका Panchthar Rural municipality 1 kummayakmun.gov.np 15 Miklajung Rural Municipality लि啍िाजुङ गाउँपालिका