Guiding Principles for U.S. Post-Conflict Policy in Iraq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Refugee Committee

Job Description Position Title: - Communication Officer Department/Country Program: South East Asia Program – Thailand Country Office Report to: Project Manager Status (full, part-time, temporary): Full-time Duty station: Bangkok, Thailand Supervisory Capacity: None Department/Country Program Description/Mission Since 1978Alight, formerly known as American Refugee Committee (ARC), has provided life-saving primary health services for refugees, internally displaced persons (IDPs), and host communities in emergency and post-conflict settings around the world. Since 1995, Alight has expanded its portfolio to include countries transitioning to longer-term development. From the program’s inception, Alight strives to build host country capacity to provide a broad range of comprehensive health care services by supporting Ministries of Health, service providers, and local communities. Alight implements innovative and inclusive solutions to ensure that all beneficiaries have ready and equal access to health care. Alight has been working in Thailand for over 30 years with camp-based refugees from Myanmar and mobile migrant population since 2004, with current projects mostly focusing in malaria interventions along Thailand Myanmar borders. In the health sector, Alight provides an essential package of primary, reproductive, maternal, and child healthcare services in several refugee camps along the border with Myanmar, providing supplies, training, and supervision of refugee staff, along with community-based education. Primary Purpose of the Position Alight is re-awarded as a Sub Recipient of the Global Fund RAI3E regional component to host the regional malaria Civil Society Organization (CSO) platform, GMS for 2021-2023. The Regional Malaria CSO Platform is a network of civil society organizations from the Global Fund RAI implementing countries: Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Lao PDR and Vietnam. -

Eliminating Violence Against Women

ELIMINATING VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN PERSPECTIVES ON HONOR-RELATED VIOLENCE IN THE IRAQI KURDISTAN REGION, SULAIMANIYA GOVERNORATE By Tanyel B. Taysi With Contributions from Norul M. Rashid Martin Bohnstedt ASUDA & UNAMI HUMAN RIGHTS OFFICE: ELIMINATING VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN FOREWORD ......................................................................................................................................3 I. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................................4 II. INTERNATIONAL, REGIONAL AND NATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS FRAMEWORKS .......................8 III. HONOR-RELATED VIOLENCE..................................................................................................14 IV. CONTEXTUAL OVERVIEW OF WOMEN’S POSITION IN IRAQI KURDISTAN ............................16 V. FINDINGS ...................................................................................................................................19 VI. SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................41 VII. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS .............................................................................43 APPENDIX.......................................................................................................................................48 Honor-related Violence in the Kurdistan Region Page 2 ASUDA & UNAMI HUMAN RIGHTS OFFICE: ELIMINATING VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN FOREWORD Honor-related -

Iraq: Buttressing Peace with the Iraqi Inter-Religious Congress

Religion and Conflict Case Study Series Iraq: Buttressing Peace with the Iraqi Inter-Religious Congress August 2013 © Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs http://berkleycenter.georgetown.edu/resources/classroom 4 Abstract 5 This case study shines a light on the sectarian violence that overtook Iraq after the 2003 US-led invasion that overthrew Saddam Hussein, and how religious 9 leaders gradually gained recognition as resources for the promotion of peace. This overview of the conflict addresses five main questions: What religious 11 factors contributed to insecurity in post-2003 Iraq? How did Coalition forces approach religious actors prior to 2006? How did governments interface with faith-based NGOs in pursuit of peace? What role did socioeconomic factors 14 play in exacerbating conflict? How did religious engagement intersect with the Sunni Awakening and the surge of Coalition troops in 2007? The case study includes a core text, a timeline of key events, a guide to relevant religious orga- nizations, and a list of further readings. 15 About this Case Study 17 This case study was crafted under the editorial direction of Eric Patterson, visiting assistant professor in the Department of Government and associate di- rector of the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs at George- town University. This case study was made possible through the support of the Henry Luce Foundation and the Luce/SFS Program on Religion and International Affairs. 2 BERKLEY CENTER FOR RELIGION, PEACE & WORLD AFFAIRS AT GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY CASE STUDY — IRAQ Contents Introduction 4 Historical Background 5 Domestic Factors 9 International Factors 11 Religion and Socioeconomic Factors 12 Conclusion 14 Resources Key Events 15 Religious Organizations 17 Further Reading 19 Discussion Questions 21 BERKLEY CENTER FOR RELIGION, PEACE & WORLD AFFAIRS AT GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY CASE STUDY — IRAQ 3 Introduction While the US invasion of Iraq—and the insurgency that a shaky relationship with the United States. -

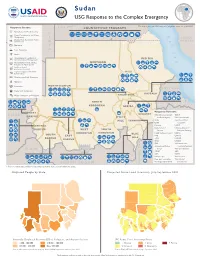

BHA Sudan Complex Emergency Fact Sheet

Sudan USG Response to the Complex Emergency This map represents USG-supported programs active as of 08/16/21. Response Sectors: EGYPT COUNTRYWIDE PROGRAMS Agriculture and Food Security LIBYA Camp Coordination and Camp R Management SAUDI Disaster Risk Reduction Policy e and Practice ARABIA Education d Food Assistance S Health e Humanitarian Coordination RED SEA and Information Management a Humanitarian Policy, Studies, NORTHERN Analysis, or Applications Livelihoods and Economic Recovery Logistics Support and Relief NILE Commodities Multipurpose Cash Assistance Nutrition Protection NORTH DARFUR ERITREA Shelter and Settlements KASSALA Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene KHARTOUM NORTH KORDOFAN GEZIRA WEST Response Partners: CHAD GEDAREF Adventist Development OCHA DARFUR WHITE and Relief Agency Relief International NILE SENNAR Alight Save the Children CARE Federation CENTRAL Concern UNDP Catholic Relief UN Department of DARFUR WEST SOUTH Services Safety and Security KORDOFAN KORDOFAN BLUE Danish Refugee Council UNFPA SOUTH EAST FAO UNHAS DARFUR NILE GOAL UNHCR DARFUR ETHIOPIA ICRC UNICEF IFRC Vétérinaires sans Abyei Area- International Medical Frontières/Germany C.A.R. Disputed* Corps War Child Canada iMMAP WFP IOM WHO Mercy Corps World Vision Near East Foundation World Relief SOUTH SUDAN Norwegian Church Aid International * Final sovereignty status of Abyei Area pending negotiations between South Sudan and Sudan. Displaced People by State Projected Acute Food Insecurity, July-September 2021 Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), Refugees, and Asylum-Seekers IPC Acute Food Insecurity Phase 1,000 - 100,000 250,001 - 500,000 1: Minimal 3: Crisis 5: Famine 100,001 - 250,000 Over 500,000 2: Stressed 4: Emergency Sources: Humanitarian Needs Overview, July 2020; UNHCR Population Dashboard, June 2021 Source: FEWS NET, Sudan Outlook, July - September 2021 The boundaries and names used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the U.S. -

What Are the Effects of US Involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan Since The

C3 TEACHERS World History and Geography II Inquiry (240-270 Minutes) What are the effects of US involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan since the Gulf War? This inquiry was designed by a group of high school students in Fairfax County Public Schools, Virginia. US Marines toppling a statue of Saddam Hussein in Firdos Square, Baghdad, on April 9, 2003 https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/the-fate-of-a-leg-of-a-statue-of-saddam-hussein Supporting Questions 1. What are the economic effects of US involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan since the Gulf War? 2. What are the political effects of US involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan since the Gulf War? 3. What are the social effects of US involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan since the Gulf War? THIS WORK IS LICENSE D UNDER A CREATIVE C OMMONS ATTRIBUTION - N ONCOMMERCIAL - SHAREAL I K E 4 . 0 INTERNATIONAL LICENS E. 1 C3 TEACHERS Overview - What are the effects of US involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan since the Gulf War? What are the effects of US involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan since the Gulf War? VUS.14 The student will apply social science skills to understand political and social conditions in the United States during the early twenty-first century. Standards and Content WHII.14 The student will apply social science skills to understand the global changes during the early twenty-first century. HOOK: Option A: Students will go through a see-think-wonder thinking routine based off the primary source Introducing the depicting the toppling of a statue of Saddam Hussein, as seen on the previous page. -

Mahama Refugee Camp Profile Rwanda

Rwanda Mahama Refugee Camp Profile as of 09 April 2021 Population : 47,695 (Congolese: 4,190 Burundians: 43,500 Others: 5) CAMP OVERVIEW CURRENT SERVICES BACKGROUND SITUATION Coordinates : The following services are available in the camp: Lat:-2.30 S2o18’18.294” Mahama camp covering 175Ha of land with a total of 6,907 duplex family shelters that accommodates 52,026 persons and 2 durable 2 health centres, 2 primary schools and 2 secondary schools, 6 youth Long:30.8 E 30o50’17.904” communal accommodation blocks constructed in the camp to support Camp Extent : 175 Hectares centres, 1 women centre, 2 multi purpose vocational training centres, 2 accommodate new arrivals before being relocated to empty shelters Av. Camp Area/Person 2 34 m food distribution centres, 1 LPG distribution centre, 1 Police post; 3 camp within the camp. Distance from border : 30 km based markets, 1 community centre. Region/District : Kirehe # of Partners : 15 Admin divisions : 9 Quartiers (18 villages) Authority : Ministry in Charge of COMMUNITY ORGANIZATION Emergency Management (MINEMA) Government of Rwanda The camp community organization is structured around three administrative layers, which are Quartier, villages and communities. Each organizational level has its elected representatives, 18 village leaders and 9 zone leaders. Both men and women are proactively incorporated in all stages of electral process. SECTOR OVERVIEW Minimum DEMOGRAPHY Sector Indicator Target Achieved Standard Key Figures Age and Gender Refugees % of identified SGBV survivors offered multi-sectorial/appropriate -

Iraq: U.S. Regime Change Efforts and Post-Saddam Governance

Order Code RL31339 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Iraq: U.S. Regime Change Efforts and Post-Saddam Governance Updated May 16, 2005 Kenneth Katzman Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Iraq: U.S. Regime Change Efforts and Post-Saddam Governance Summary Operation Iraqi Freedom accomplished a long-standing U.S. objective, the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, but replacing his regime with a stable, moderate, democratic political structure has been complicated by a persistent Sunni Arab-led insurgency. The Bush Administration asserts that establishing democracy in Iraq will catalyze the promotion of democracy throughout the Middle East. The desired outcome would also likely prevent Iraq from becoming a sanctuary for terrorists, a key recommendation of the 9/11 Commission report. The Bush Administration asserts that U.S. policy in Iraq is now showing substantial success, demonstrated by January 30, 2005 elections that chose a National Assembly, and progress in building Iraq’s various security forces. The Administration says it expects that the current transition roadmap — including votes on a permanent constitution by October 31, 2005 and for a permanent government by December 15, 2005 — are being implemented. Others believe the insurgency is widespread, as shown by its recent attacks, and that the Iraqi government could not stand on its own were U.S. and allied international forces to withdraw from Iraq. Some U.S. commanders and senior intelligence officials say that some Islamic militants have entered Iraq since Saddam Hussein fell, to fight what they see as a new “jihad” (Islamic war) against the United States. -

Unhcr and Partner Practices Of

UNHCR AND PARTNER PRACTICES OF COMMUNITY-BASED PROTECTION ACROSS SECTORS IN THE EAST AND HORN OF AFRICA AND THE GREAT LAKES REGION SUGGESTED CITATION Charles Mballa, Josephine Ngebeh, Machtelt De Vriese, Katie Drew, Abigayil Parr, Chi-Chi Undie. 2020. UNHCR and Partner Practices of Community-Based Protection across Sectors in the East and Horn of Africa and the Great Lakes Region. UNHCR and Population Council. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS 2 FOREWORD 3 INTRODUCTION 4 METHODOLOGY 5 HIGHLIGHTS OF PROMISING PRACTICES 7 COMPENDIUM OF PRACTICES 9 COVID-RELATED PRACTICES 9 1. CHILD PROTECTION AND YOUTH 9 2. COMMUNITY-BASED PROTECTION 35 3. SGBV/RISK MITIGATION/RESPONSE 26 NON-COVID-RELATED PRACTICES 28 1. CHILD PROTECTION AND YOUTH 28 2. COMMUNITY-BASED PROTECTION 35 3. GENDER EQUALITY 51 4. SGBV/RISK MITIGATION/RESPONSE 54 1 UNHCR AND PARTNER PRACTICES OF COMMUNITY-BASED PROTECTION ACROSS SECTORS IN THE EAST AND HORN OF AFRICA AND THE GREAT LAKES REGION ACRONYMS AGD Age, Gender, and Diversity ARRA Agency for Refugee and Returnee Affairs CBAC Community-Based Adolescent Committee CBP Community-Based Protection CCCT Community Care Coalition Team CHH Child-Headed Household CHW Community Health Worker CORPS Community Owned Resource Person CPC Child Protection Committee CPV Child Protection Volunteer CRRF Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework CWC Child Welfare Committee DICAC Development and Inter-Church Aid Commission DRC Danish Refugee Council DHR Direction de l’Hydraulique Rurale EHAGL East and Horn of Africa and the Great Lakes FDP Food Distribution -

Syria and Iraq: Update by Ben Smith and Claire Mills July 2017

BRIEFING PAPER Number CBP 8011, 21 July 2017 Syria and Iraq: update By Ben Smith and Claire Mills July 2017 Contents: 1. ISIS situational report 2. The military campaign 3. Political analysis 4. International humanitarian law 5. Human cost www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Syria and Iraq: update July 2017 Contents Summary 3 1. ISIS situational report 5 Iraq 6 Syria 9 2. The military campaign 13 2.1 The Trump administration’s comprehensive military strategy 13 2.2 Who are the main players in the campaign? 14 Air campaign 14 Train, advise and assist mission 15 2.3 British participation 17 Training 18 3. Political analysis 19 Syria 19 Kurds 23 Iran 24 Iraq 25 Shifting alliances 27 Qatar 27 Future of ISIS 28 4. International humanitarian law 30 5. Human cost 32 Casualties of the conflict 32 Humanitarian 34 5.1 UK aid in the region 34 Contributing Authors: Terry McGuinness, Overseas aid, 5.1 Cover page image copyright: Syrian rebels in Qaboun by Qasioun News Agency. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license / image cropped. 3 Commons Library Briefing, 21 July 2017 Summary ISIS has now lost over 70% of the territory it once held in Iraq, and 51% of its territory in Syria. In a significant blow to ISIS, the Iraqi city of Mosul was liberated by Iraqi Security Forces on 10 July 2017, after nine months of fighting. Attention is now turning to the remaining areas of Iraq under ISIS control including the cities of Tal Afar and Hawija in Western Iraq and smaller towns in the Euphrates River Valley; and ISIS’ self-declared ‘capital’, al-Raqqa, in Syria. -

Amnesty International VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN

Amnesty International VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN Human Rights Education Activities for use in teaching Personal Social and Health Education, Citizenship and English for ages 11-18 HUMAN RIGHTS EDUcation RESOURCE WOMEN’S RIGHTS SECTION 2 The activities in this section are: ACTIVITY 1 Facts about violence against women Ages: 11+ 4 ACTIVITY 2 Is this OK? Ages: 11+ 7 ACTIVITY 3 Domestic violence Ages: 11+ 8 ACTIVITY 4 Problem, what problem? Ages: 15+ 11 ACTIVITY 5 Rape Ages: 15+ 13 ACTIVITY 6 Campaigns to stop gender violence Ages: 15+ 16 One important issue, not covered by any specific activity in this section, but referred to in the text, is Female Genital Mutilation (FGM). You can find information on this subject on these websites: http://www.stopfgmc.org/ www.ipu.org/wmn-e/fgm.htm www.amnesty.org.uk/education TEACHE INTRODUCTION FOR TEACHERS ‘Violence against women is perhaps the most shameful human rights violation, and it is perhaps the most pervasive. It knows no boundaries of geography, culture or wealth. As long as it R continues, we cannot claim to be making real progress towards NOTES equality, development and peace.’ Kofi Annan, UN Secretary General All human rights issues affect women. The activities in this resource comprises However, women also suffer specific denial the second in a series of three sets of of their human rights because of their activities on women and human rights that gender. The experience or threat of violence aim to help students to think about violence affects the lives of millions of women against women as a human rights issue, and everywhere, cutting across boundaries of to explore its causes and consequences: age, wealth, race, religion, sexual identity and culture. -

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION IRAQ at a CROSSROADS with BARHAM SALIH DEPUTY PRIME MINISTER of IRAQ Washington, D.C. Monday, October

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION IRAQ AT A CROSSROADS WITH BARHAM SALIH DEPUTY PRIME MINISTER OF IRAQ Washington, D.C. Monday, October 22, 2007 Introduction and Moderator: MARTIN INDYK Senior Fellow and Director, Saban Center for Middle East Policy The Brookings Institution Featured Speaker: BARHAM SALIH Deputy Prime Minister of Iraq * * * * * 2 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. INDYK: Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. Welcome to The Saban Center for Middle East Policy at the Brookings Institution. I'm Martin Indyk, the Director of the Saban Center, and it's my pleasure to introduce this dear friend, Dr. Barham Salih, to you again. I say again because, of course, Barham Salih is a well-known personality in Washington, having served here with distinction representing the patriotic Union of Kurdistan in the 1990s, and, of course, he's been a frequent visitor since he assumed his current position as Deputy Prime Minister of the Republic of Iraq. He has a very distinguished record as a representative of the PUK, and the Kurdistan regional government. He has served as Deputy Prime Minister, first in the Iraqi interim government starting in 2004, and was then successfully elected to the transitional National Assembly during the January 2005 elections and joined the transitional government as Minister of Planning. He was elected again in the elections of December 2005 to the Council of Representatives, which is the Iraqi Permanent Parliament, and was then called upon to join the Iraqi government in May 2006 as Deputy Prime Minister. Throughout this period he has had special responsibility for economic affairs. -

2021 South Sudan Regional Refugee Response Plan

SOUTH SUDAN REGIONAL REFUGEE RESPONSE PLAN January 2020 — December 2021 Updated in March 2021 CREDITS: UNHCR wishes to acknowledge the contributions of partners and staff in the field, Regional Bureau in Nairobi and Headquarters who have participated in the preparation of the narrative, financial and graphic components of this document. Production: UNHCR, Regional Bureau for East and Horn of Africa, and the Great Lakes The maps in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of UNHCR concerning the legal status of any country or territory or area, of its authorities, or the delimitation of frontiers or boundaries. All statistics are provisional and subject to change. For more information on the South Sudan crisis go to: South Sudan Information Sharing Portal FRONT COVER PHOTOGRAPH: South Sudanese refugees walk through Jewi refugee camp in Ethiopia. ©UNHCR / Eduardo Soteras Jalil SOUTH SUDAN REGIONAL RRP Contents Regional Refugee Response Plan 3 Foreword 4 Introduction 7 Regional Protection and Solutions Analysis 11 Regional Response Strategy and Priorities 14 Partnership and Coordination 20 Financial Requirements 22 The Democratic Republic of the Congo - summary plan Background 31 Needs Analysis 32 Response Strategy and Priorities 34 Partnership and Coordination 35 Financial Requirements 36 Ethiopia - summary plan Background 39 Needs Analysis 41 Response Strategy and Priorities 43 Partnership and Coordination 44 Financial Requirements 45 Kenya - summary plan Background 48 Needs Analysis 49 Response Strategy and