Season 2014-2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Production Database Updated As of 25Nov2020

American Composers Orchestra Works Performed Workshopped from 1977-2020 firstname middlename lastname Date eventype venue work title suffix premiere commission year written Michael Abene 4/25/04 Concert LGCH Improv ACO 2004 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Piano Improv Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Duet for Violin & Piano Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Duet for Double Bass & Piano Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/9/00 Concert CH Tomorrow's Song, as Yesterday Sings Today World 2000 Ricardo Lorenz Abreu 12/4/94 Concert CH Concierto para orquesta U.S. 1900 John Adams 4/25/83 Concert TULLY Shaker Loops World 1978 John Adams 1/11/87 Concert CH Chairman Dances, The New York ACO-Goelet 1985 John Adams 1/28/90 Concert CH Short Ride in a Fast Machine Albany Symphony 1986 John Adams 12/5/93 Concert CH El Dorado New York Fromm 1991 John Adams 5/17/94 Concert CH Tromba Lontana strings; 3 perc; hp; 2hn; 2tbn; saxophone1900 quartet John Adams 10/8/03 Concert CH Christian Zeal and Activity ACO 1973 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH The Wound-Dresser 1988 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH My Father Knew Charles Ives ACO 2003 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH Violin Concerto 1993 John Luther Adams 10/15/10 Concert ZANKL The Light Within World 2010 Victor Adan 10/16/11 Concert MILLR Tractus World 0 Judah Adashi 10/23/15 Concert ZANKL Sestina World 2015 Julia Adolphe 6/3/14 Reading FISHE Dark Sand, Sifting Light 2014 Kati Agocs 2/20/09 Concert ZANKL Pearls World 2008 Kati Agocs 2/22/09 Concert IHOUS -

Network Notebook

Network Notebook Summer Quarter 2017 (July - September) A World of Services for Our Affiliates We make great radio as affordable as possible: • Our production costs are primarily covered by our arts partners and outside funding, not from our affiliates, marketing or sales. • Affiliation fees only apply when a station takes three or more programs. The actual affiliation fee is based on a station’s market share. Affiliates are not charged fees for the selection of WFMT Radio Network programs on the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). • The cost of our Beethoven and Jazz Network overnight services is based on a sliding scale, depending on the number of hours you use (the more hours you use, the lower the hourly rate). We also offer reduced Beethoven and Jazz Network rates for HD broadcast. Through PRX, you can schedule any hour of the Beethoven or Jazz Network throughout the day and the files are delivered a week in advance for maximum flexibility. We provide highly skilled technical support: • Programs are available through the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). PRX delivers files to you days in advance so you can schedule them for broadcast at your convenience. We provide technical support in conjunction with PRX to answer all your distribution questions. In cases of emergency or for use as an alternate distribution platform, we also offer an FTP (File Transfer Protocol), which is kept up to date with all of our series and specials. We keep you informed about our shows and help you promote them to your listeners: • Affiliates receive our quarterly Network Notebook with all our program offerings, and our regular online WFMT Radio Network Newsletter, with news updates, previews of upcoming shows and more. -

Jennifer Higdon-Large Full

Pulitzer Prize and two-time Grammy-winner Jennifer Higdon (b. Brooklyn, NY, December 31, 1962) taught herself to play flute at the age of 15 and began formal musical studies at 18, with an even later start in composition at the age of 21. Despite these obstacles, Jennifer has become a major figure in contemporary Classical music. Her works represent a wide range of genres, from orchestral to chamber, to wind ensemble, as well as vocal, choral and opera. Her music has been hailed by Fanfare Magazine as having “the distinction of being at once complex, sophisticated but readily accessible emotionally”, with the Times of London citing it as “…traditionally rooted, yet imbued with integrity and freshness.” The League of American Orchestras reports that she is one of America's most frequently performed composers. Higdon's list of commissioners is extensive and includes The Philadelphia Orchestra, The Chicago Symphony, The Atlanta Symphony, The Cleveland Orchestra, The Minnesota Orchestra, The Pittsburgh Symphony, the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra, as well such groups as the Tokyo String Quartet, the Lark Quartet, Eighth Blackbird, and the President’s Own Marine Band. She has also written works for such artists as baritone Thomas Hampson, pianists Yuja Wang and Gary Graffman, violinists Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg, Jennifer Koh and Hilary Hahn. Her first opera, Cold Mountain, won the prestigious International Opera Award for Best World Premiere in 2016; the first American opera to do so in the award’s history. Performances of Cold Mountain sold out its premiere run in Santa Fe, North Carolina, and Philadelphia (becoming the third highest selling opera in Opera Philadelphia’s history). -

Boston University Symphony Orchestra

BOSTON UNIVERSITY SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Wednesday, November 20, 2019 Tsai Performance Center BOSTON UNIVERSITY Founded in 1839, Boston University is an internationally recognized institution of higher education and research. With more than 33,000 students, it is the fourth-largest independent university in the United States. BU consists of 16 schools and colleges, along with a number of multi-disciplinary centers and institutes integral to the University’s research and teaching mission. In 2012, BU joined the Association of American Universities (AAU), a consortium of 62 leading research universities in the United States and Canada. BOSTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS Established in 1954, Boston University College of Fine Arts (CFA) is a community of artist-scholars and scholar-artists who are passionate about the fine and performing arts, committed to diversity and inclusion, and determined to improve the lives of others through art. With programs in Music, Theatre, and Visual Arts, CFA prepares students for a meaningful creative life by developing their intellectual capacity to create art, shift perspective, think broadly, and master relevant 21st century skills. CFA offers a wide array of undergraduate, graduate, and doctoral programs, as well as a range of online degrees and certificates. Learn more at bu.edu/ cfa. BOSTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS SCHOOL OF MUSIC Founded in 1872, Boston University College of Fine Arts School of Music combines the intimacy and intensity of traditional conservatory-style training with a broad liberal arts education at the undergraduate level, and elective coursework at the graduate level. The school offers degrees in performance, conducting, composition and theory, musicology, music education, and historical performance, as well as artist and performance diplomas and a certificate program in its Opera Institute. -

REPERTOIRE CONDUCTED in PERFORMANCE Current March 2020

REUBEN BLUNDELL – CONDUCTOR REPERTOIRE CONDUCTED IN PERFORMANCE Current March 2020 Information concerning premiere recording of American Romantics, including reviews: http://www.newfocusrecordings.com/catalogue/gowanus-arts-ensemble-american-romantics/ http://www.newfocusrecordings.com/catalogue/gowanus-arts-ensemble-american-romantics-ii/ http://www.newfocusrecordings.com/catalogue/reuben-blundell-lansdowne-symphony-orchestra-american-romantics-iii/ John Adams Ludwig van Beethoven The Chairman Dances Ah! perfido Coriolanus Overture Elfrida Andrée Creatures of Prometheus Overture Andante quasi recitativo Egmont Overture Leonore Overture No. 1 Anton Arensky Name Day Overture Variations on a Theme by Tchaikovsky Symphonies 1 & 3-8 Johann Sebastian Bach Seth Bedford The Art of Fugue Flushing Meadow 1964* Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 Freedom from Fear* Concerto for Two Violins In a Snowy Day* Orchestral Suite No. 3 Samuel Beebe Samuel Barber The Rest is Silence* Adagio for Strings Overture to the School for Scandal Jeanne Behrend Concert Fanfare Béla Bartók Concerto for Orchestra Jennifer Bellor Concerto for Viola (Serly ed.) Air and Angels* Old Hungarian Dances Echo's Lament* Rumanian Folk Dances, Str/Orch Two Pictures Alban Berg Chamber Concerto María de Baratta Danza del Incienzo Hector Berlioz Hungarian March from Faust Randol Alan Bass Symphony Fantastique A Christmas Flourish Seasonal Sounds Leonard Bernstein Concert Suite from West Side Story Mason Bates The B-Sides Georges Bizet Carmen Suite No. 1 Priscilla Beach Suite from L’Arlesienne -

Enigma Lawrence Symphony Orchestra Mark Dupere, Conductor

Enigma Lawrence Symphony Orchestra Mark Dupere, conductor Ned Martenis, flute Co-winner, LSO Concerto Competition Friday, May 31, 2019 8:00 p.m. Lawrence Memorial Chapel City Scape Jennifer Higdon III. Peachtree Street (b. 1962) Concerto for Flute and Chamber Orchestra Christian Lindberg “The World of Montuagretta” (b. 1958) I. Isola: Adagio - Mandarena: Allegro vivo II. Cadenza, “Horry the Lorry”: Rubato ironico III. Dreams of Arkandia: Lento IV. Cadenza Impala: Adagio - Rubato imposante V. Moriatto Bianco: Vivace - Chorale - Vivace Ned Martenis, flute Co-winner, LSO Concerto Competition ▪ INTERMISSION ▪ Variations on an Original Theme for Orchestra, op. 36 (“Enigma”) Edward Elgar Theme (1857-1934) I. (C.A.E.) II. (H.D.S-P.) III. (R.B.T.) IV. (W.M.B.) V. (R.P.A.) VI. (Ysobel) VII. (Troyte) VIII. (W.N.) IX. (Nimrod) X. Intermezzo (Dorabella) XI. (G.R.S.) XII. (B.G.N.) XIII. Romanza (***) XIV. Finale (E.D.U.) Please join us for a reception in SH163 following the performance. In 2018 all lighting in Memorial Chapel was updated to LED. Spray foam insulation with an R- value of R40 was added to the attic. The savings associated with these projects are estimated to be more than 105,000 kilowatt hours and $10,000 per year. Project funded in part by the LUCC Environmental Sustainability Fund. Composer’s Note for “Peachtree Street” “Peachtree Street” from City Scape The final movement, “Peachtree Street,” is a representation of all those roadways and main arteries that flow through cities (Peachtree Street is the main street that runs through downtown Atlanta, the city of my childhood). -

Celebrating 175 Years in New York Alan Gilbert's Farewell Season

FOR RELEASE: February 3, 2016 Contact: Katherine E. Johnson NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC 2016–17 SEASON — CELEBRATING 175 YEARS IN NEW YORK ALAN GILBERT’S FAREWELL SEASON OPENING GALA CONCERT: New York Philharmonic Premieres Past and Present THE NEW WORLD INITIATIVE: Season-Long, Citywide Immersion in DVOŘÁK’S NEW WORLD SYMPHONY THE NEW YORK COMMISSIONS: Works on NEW YORK Theme by New York–Based WYNTON MARSALIS, SEAN SHEPHERD, and JULIA WOLFE THE ART OF THE SCORE: Film Week at the Philharmonic Celebrates New York MANHATTAN & WEST SIDE STORY SPRING GALA: BREAKFAST AT TIFFANY’S ALAN GILBERT’S FAREWELL SEASON HIGHLIGHTS SEVEN PREMIERES, FINAL EUROPE TOUR, WAGNER’s Das Rheingold, MAHLER’s Fourth Symphony, BEETHOVEN’s Ninth Symphony with SCHOENBERG’s A Survivor from Warsaw, JOHN ADAMS’s 70th Birthday, LIGETI’s Mysteries of the Macabre, HANDEL’s Messiah, and More SEASON FINALE: A Program Exploring How Music Can Effect Positive Change and Harmony in the World ______________________________________ BELOVED FRIEND — TCHAIKOVSKY AND HIS WORLD: A Philharmonic Festival Conducted by SEMYON BYCHKOV Violinist LEONIDAS KAVAKOS: The Mary and James G. Wallach ARTIST-IN-RESIDENCE ESA-PEKKA SALONEN: Second Season as The Marie-Josée Kravis COMPOSER-IN-RESIDENCE Pianist INON BARNATAN: Final Season as Inaugural ARTIST-IN-ASSOCIATION ______________________________________ Additional Philharmonic Commissions by JULIA ADOLPHE, LERA AUERBACH, TANSY DAVIES, HK GRUBER, ESA-PEKKA SALONEN, and XU SHUYA PHILHARMONIC’S NEXT MUSIC DIRECTOR JAAP VAN ZWEDEN To Return Appearances -

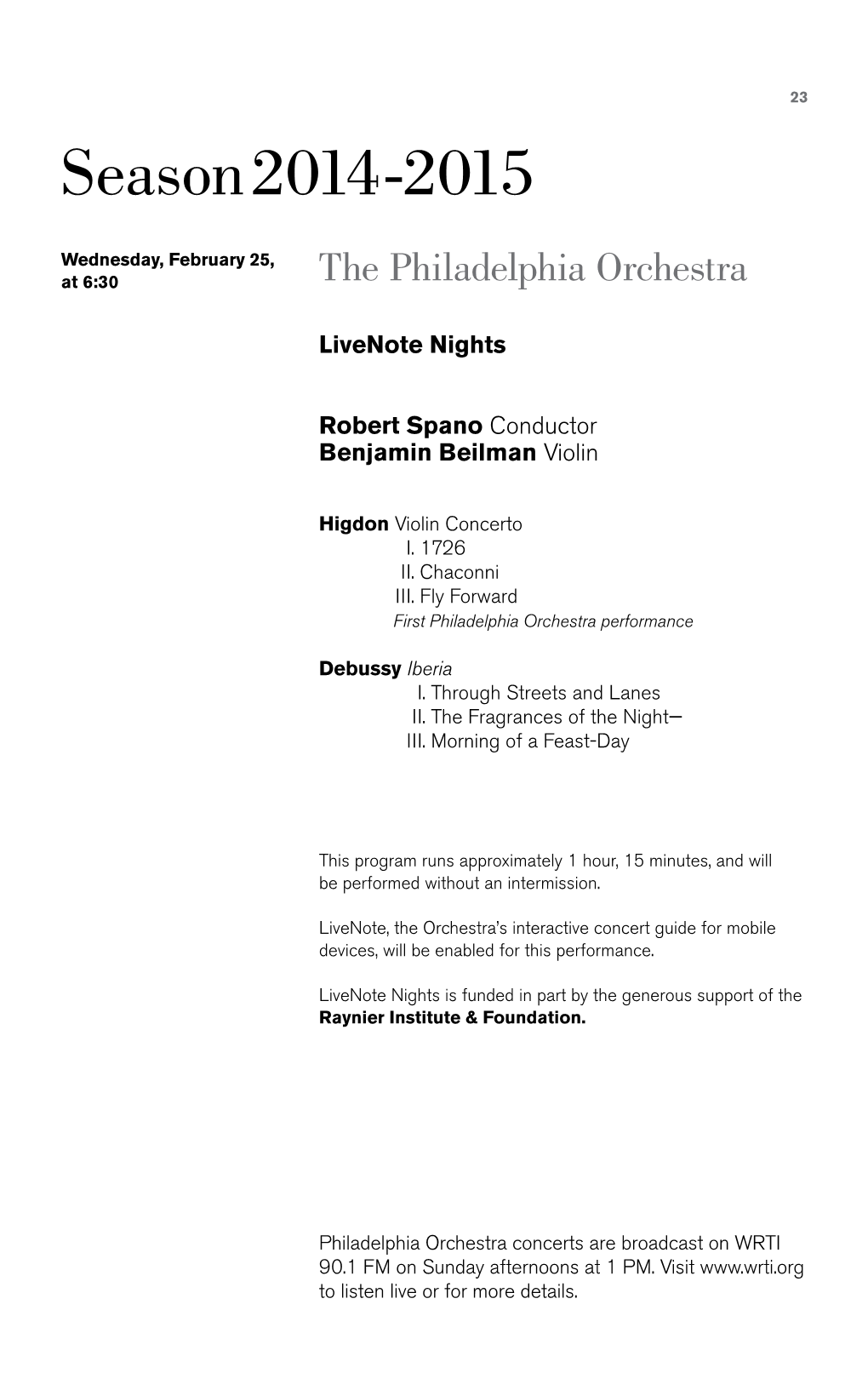

Season 2014-2015

23 Season 2014-2015 Thursday, February 26, at 8:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, February 27, at 2:00 Saturday, February 28, at 8:00 Robert Spano Conductor Benjamin Beilman Violin Debussy/ “The Sunken Cathedral,” from Preludes orch. Stokowski Higdon Violin Concerto I. 1726 II. Chaconni III. Fly Forward Intermission Higdon blue cathedral Debussy Iberia I. Through Streets and Lanes II. The Fragrances of the Night— III. Morning of a Feast-Day This program runs approximately 1 hour, 45 minutes. designates a work that is part of the 40/40 Project, which features pieces not performed on subscription concerts in at least 40 years. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 224 Story Title The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra is one of the preeminent orchestras in the world, renowned for its distinctive sound, desired for its keen ability to capture the hearts and imaginations of audiences, and admired for a legacy of imagination and innovation on and off the concert stage. The Orchestra is transforming its rich tradition of achievement, sustaining the highest level of artistic quality, but also challenging—and exceeding—that level by creating powerful musical experiences for audiences at home and around the world. Music Director Yannick Nézet-Séguin’s highly collaborative style, deeply-rooted musical curiosity, and boundless enthusiasm, paired with a fresh approach to orchestral programming, have been heralded by critics and audiences alike since his inaugural season in 2012. Under his leadership the Orchestra returned to recording with a celebrated CD of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring and Leopold Stokowski transcriptions on the Deutsche Grammophon label, continuing its history of recording success. -

Download Program Here

DC CO Connecticut Avenue Wine & Liquor is proud to support the DC Concert Orchestra For all your beverage and entertaining needs, please visit us at 1529 Connecticut Ave., NW. Washington, DC 20036 202-332-0240 [email protected] Program The DC Concert Orchestra Society presents a concert by The DC Concert Orchestra Randall Stewart, Music Director Sunday, May 5, 2019, 3:00 p.m. Church of The Epiphany Giovanni Gabrieli Sonata Octavi Toni Jennifer Higdon blue cathedral Bedřich Smetana Ma Vlast II. Vlatava INTERMISSION (15 minutes) Éduoard Lalo Symphonie Espagnole I. Allegro non troppo Eugene Kim, Violin Ottorino Respighi Pini di Roma I. I Pini di Villa Borghese II. Pini pressa una Catacomba III. I Pini del Giancolo IV. I Pini della Via Appia Contributions to the DC Concert Orchestra Society are greatly appreciated. To donate, visit: dccos.org/donate-DCCO Music Director Randall Stewart Randall Stewart, Music Director of the DCCO since 2014, previously served as the Associate Conductor of the Columbia Orchestra and Music Director of the Baltimore Sinfonietta. As a guest conductor, he has led the Catholic University Symphony Orchestra, the Anne Arundel Community College Orchestra, and the D.C. Youth Orchestra Program. As an opera conductor, he has led performances of Catholic University’s productions of The Merry Widow and L’incoronazione di Poppea, as well as productions of Il Barbiere di Siviglia, Le Nozze di Figaro, and Die Zauberflöte for coópera (New York City). A passionate advocate of American composers, Maestro Stewart led performances of works by Ives, Copland, Barber, and Schuman, as well as contemporary works by Eric Whitacre and Michael Daugherty. -

2014 Festival of Contemporary Music Has Been Endowed in Perpetuity by the Generosity of Dr

TANGLEWOOD MUSIC CENTER an activity of the Boston Symphony Orchestra Andris Nelsons, Ray and Maria Stata Music Director Designate Mark Volpe, Eunice and Julian Cohen Managing Director, endowed in perpetuity Ellen Highstein, Edward H. Linde Tanglewood Music Center Director, endowed by Alan S. Bressler and Edward I. Rudman Tanglewood Music Center Staff Library Anna Doane John Perkel Mary Murray Karen Leopardi Melissa Steinberg TMC Resident Assistants Associate Director for Faculty Orchestra Librarians Ellie Rutledge and Guest Artists Audrey Dunne Residential Office Assistant Michael Nock Head Librarian, Copland Associate Director for Library Audio Department Student Affairs Carlos Garcia Tim Martyn, Gary Wallen Assistant Librarian, Technical Director/Chief Associate Director for Copland Library Engineer Scheduling and Production Douglas McKinnie Production Audio Engineer, Head of Live Sound 2013 SUMMER STAFF John Morin Stage Manager, Seiji Ozawa Charlie Post Chief Audio Engineer, Administrative Hall Benjamin Honeycutt Ozawa Hall Ryland Bennett Assistant Stage Manager, Nicholas Squire Personnel Manager Seiji Ozawa Hall Audio Engineer and Kristie Chan Matt Costa Assistant Radio Engineer Artist Assistant/Driver Mike Martin Joel Watts Sonya Knussen Andrew Maskiell Associate Audio Engineer Office Coordinator Ryan Mix Meghan Ryan Stage Assistants, Seiji Ozawa Piano Programs and Scheduling Hall Assistant Steve Carver Chief Piano Technician Hannah Scott Residential Front Desk Assistant Barbara Renner Peter Lillpopp Chief Piano Technician TMC Residential -

The Choral Works of Jennifer Higdon

The Choral Works of Jennifer Higdon The Choral Works of Jennifer Higdon: Choral Kaleidoscope By William Skoog Edited by Meagan Mason The Choral Works of Jennifer Higdon: Choral Kaleidoscope By William Skoog This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by William Skoog All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6868-7 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6868-6 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................. vii Preface ....................................................................................................... ix Foreword .................................................................................................. xii Jocelyn Hagen Chapter 1 .................................................................................................... 1 Introduction Chapter 2 .................................................................................................... 5 The Singing Rooms Chapter 3 .................................................................................................. 46 On the Death of the Righteous Chapter -

Comprehensive Analysis of Movement One of Jennifer Higdon’S Violin Concerto

COMPREHENSIVE ANALYSIS OF MOVEMENT ONE OF JENNIFER HIGDON’S VIOLIN CONCERTO By Brittany J. Green July 2018 Director of Thesis: Dr. Mark Richardson Major Department: Music Theory, Composition, and Musicology Jennifer Higdon (b. 1962) is quickly becoming one of the most performed and sought after American composers of our time. Her works have been played by all major American orchestras, along with several major European orchestras. As a Pulitzer Prize and multiple Grammy winner, she writes exclusively for commissions and her music is an audience favorite among concertgoers. The primary focus of this research is to investigate the first movement of Jennifer Higdon’s Violin Concerto, addressing concerns of linear and contrapuntal development, along with the harmonic language employed in this movement, to prove that these traits are at the heart of Higdon’s compositional voice and are what make her works accessible, yet engaging. The thesis will then provide a formal analysis of the complete work, noting key elements of each movement and notable connections between the three movements. A formal analysis of the first movement will then be provided. Following these formal analyses, a discussion of pitch collection, voice-leading, motivic development, linear unfoldings and contrapuntal devices utilized in the first movement will be explored, including parallels between the movement’s title, 1726, and the pitch and intervallic content exploited throughout the movement. Next, Higdon’s harmonic language will be examined, with discourse regarding