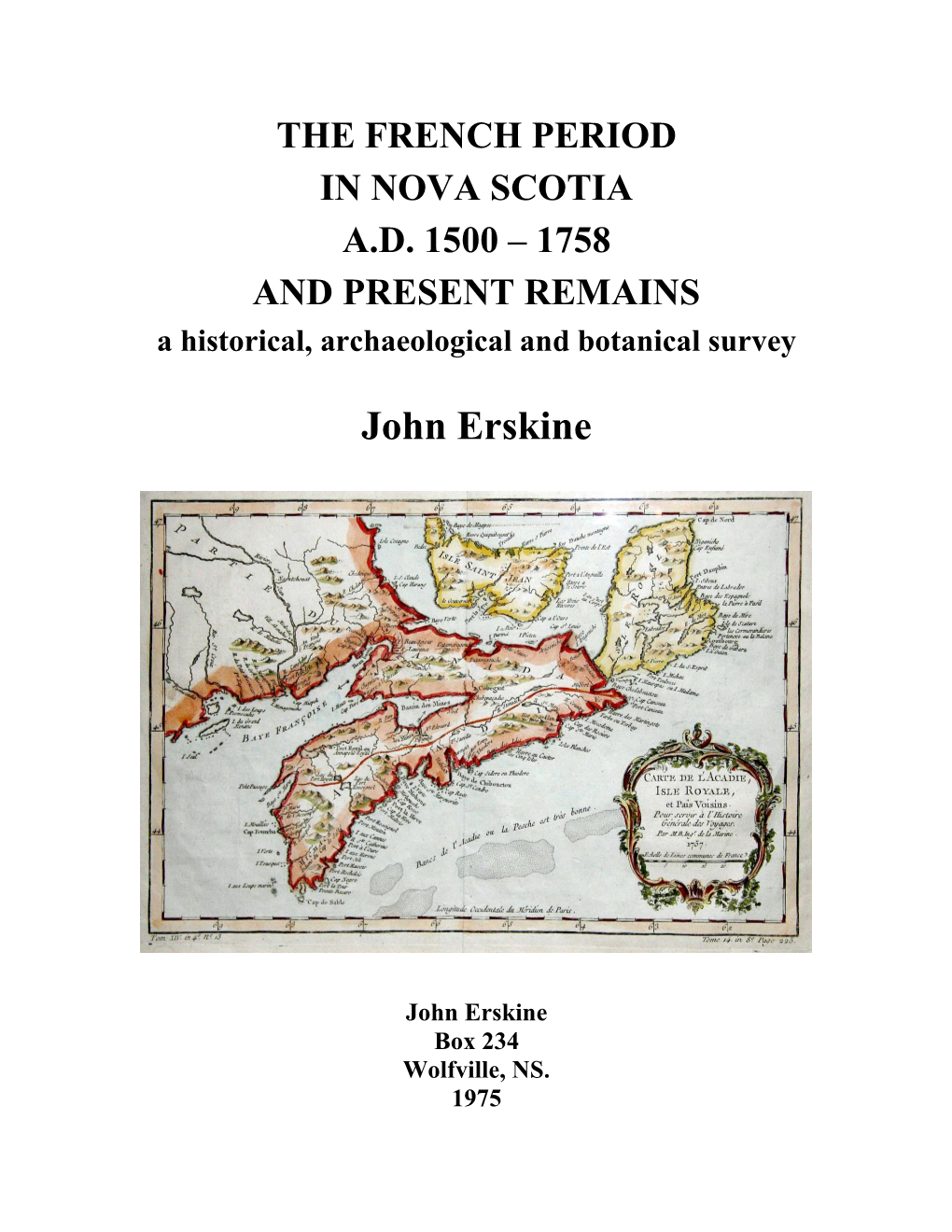

Remains of French Period in NS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barriers to Fish Passage in Nova Scotia the Evolution of Water Control Barriers in Nova Scotia’S Watershed

Dalhousie University- Environmental Science Barriers to Fish Passage in Nova Scotia The Evolution of Water Control Barriers in Nova Scotia’s Watershed By: Gillian Fielding Supervisor: Shannon Sterling Submitted for ENVS 4901- Environmental Science Honours Abstract Loss of connectivity throughout river systems is one of the most serious effects dams impose on migrating fish species. I examine the extent and dates of aquatic habitat loss due to dam construction in two key salmon regions in Nova Scotia: Inner Bay of Fundy (IBoF) and the Southern Uplands (SU). This work is possible due to the recent progress in the water control structure inventory for the province of Nova Scotia (NSWCD) by Nova Scotia Environment. Findings indicate that 586 dams have been documented in the NSWCD inventory for the entire province. The most common main purpose of dams built throughout Nova Scotia is for hydropower production (21%) and only 14% of dams in the database contain associated fish passage technology. Findings indicate that the SU is impacted by 279 dams, resulting in an upstream habitat loss of 3,008 km of stream length, equivalent to 9.28% of the total stream length within the SU. The most extensive amount of loss occurred from 1920-1930. The IBoF was found to have 131 dams resulting in an upstream habitat loss of 1, 299 km of stream length, equivalent to 7.1% of total stream length. The most extensive amount of upstream habitat loss occurred from 1930-1940. I also examined if given what I have learned about the locations and dates of dam installations, are existent fish population data sufficient to assess the impacts of dams on the IBoF and SU Atlantic salmon populations in Nova Scotia? Results indicate that dams have caused a widespread upstream loss of freshwater habitat in Nova Scotia howeverfish population data do not exist to examine the direct impact of dam construction on the IBoF and SU Atlantic salmon populations in Nova Scotia. -

Acadia National Park: Random Notes on the Significance of the Name William Otis Sawtelle

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine History Documents Special Collections 1929 Acadia National Park: Random Notes on the Significance of the Name William Otis Sawtelle Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory Part of the History Commons Repository Citation Sawtelle, William Otis, "Acadia National Park: Random Notes on the Significance of the Name" (1929). Maine History Documents. 83. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory/83 This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pamp 1710 ~ ----------------------~ Acadia National Park RANDOM NOTES on the SIGNIFICANCE of the NAME ~I By WILLIAM OTIS SAWTELLE Curator of the Islesford Collection, Inc. Reprinted trom The Bar Harbor TIMES. April . 1929 ACADIA NATIONAL PARK RANDOM NOTES on the SIGNIFICANCE of the NAME By WILLIAM ons SAWTELLE Curator of the Islesford Collection, Inc. ACADIA. NATIONAL PARK In the issue of December 12, 1928, there appeared in the BAR HARBOR TIMES a news item which attracted considerable attention and favorable comment. It was to the effect that Congressman John E. Nelson of the Third Maine District had, on December 10, introduced a bill in the House providing for the enlargement of Lafayette National Park and for changing the name to Acadia National Park; that the bill was introduced at the request of Superintendent George B. Dorr, and that Senator Frederick Hale would introduce an identical bill in the Senate. -

The Siege of Fort Beauséjour by Chris M. Hand Notes

1 The Siege of Fort Beauséjour by Chris M. Hand Notes Early Conflict in Nova Scotia 1604-1749. By the end of the 1600’s the area was decidedly French. 1713 Treaty of Utrecht After nearly 25 years of continuous war, France ceded Acadia to Britain. French and English disagreed over what actually made up Acadia. The British claimed all of Acadia, the current province of New Brunswick and parts of the current state of Maine. The French conceded Nova Scotia proper but refused to concede what is now New Brunswick and northern Maine, as well as modern Prince Edward Island and Cape Breton. They also chose to limit British ownership along the Chignecto Isthmus and also harboured ambitions to win back the peninsula and most of the Acadian settlers who, after 1713, became subjects of the British Crown. The defacto frontier lay along the Chignecto Isthmus which separates the Bay of Fundy from the Northumberland Strait on the north. Without the Isthmus and the river system to the west, France’s greatest colony along the St. Lawrence River would be completely cut off from November to April. Chignecto was the halfway house between Quebec and Louisbourg. 1721 Paul Mascarene, British governor of Nova Scotia, suggested that a small fort could be built on the neck with a garrison of 150 men. a) one atthe ridge of land at the Acadian town of Beaubassin (now Fort Lawrence) or b) one more west on the more prominent Beauséjour ridge. This never happened because British were busy fighting Mi’kmaq who were incited and abetted by the French. -

Guide to the Atlantic Provinces ' Published by Parks Canada Under Authority Ot the Hon

Parks Pares Canada Canada Atlantic Guide to the Atlantic Provinces ' Published by Parks Canada under authority ot the Hon. J. Hugh Faulkner Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs, Ottawa, 1978. QS-7055-000-EE-A1 Catalogue No. R62-101/1978 ISBN 0-662-01630-0 Illustration credits: Drawings of national historic parks and sites by C. W. Kettlewell. Photo credits: Photos by Ted Grant except photo on page 21 by J. Foley. Design: Judith Gregory, Design Partnership. Cette publication est aussi disponible en français. Cover: Cape Breton Highlands National Park Introduction Visitors to Canada's Atlantic provinces will find a warm welcome in one of the most beautiful and interesting parts of our country. This guide describes briefly each of the seven national parks, 19 national historic parks and sites and the St. Peters Canal, all of which are operated by Parks Canada for the education, benefit and enjoyment of all Canadians. The Parliament of Canada has set aside these places to be preserved for 3 all time as reminders of the great beauty of our land and the achievements of its founders. More detailed information on any of the parks or sites described in this guide may be obtained by writing to: Director Parks Canada Atlantic Region Historic Properties Upper Water Street Halifax, Nova Scotia B3J1S9 Port Royal Habitation National Historic Park National Parks and National Historic 1 St. Andrews Blockhouse 19 Fort Amherst Parks and Sites in the Atlantic 2 Carleton Martello Tower 20 Province House Provinces: 3 Fundy National Park 21 Prince Edward Island National Park 4 Fort Beausejour 22 Gros Morne National Park 5 Kouchibouguac National Park 23 Port au Choix 6 Fort Edward 24 L'Anse aux Meadows 7 Grand Pré 25 Terra Nova National Park 8 Fort Anne 26 Signal Hill 9 Port Royal 27 Cape Spear Lighthouse 10 Kejimkujik National Park 28 Castle Hill 11 Historic Properties 12 Halifax Citadel 4 13 Prince of Wales Martello Tower 14 York Redoubt 15 Fortress of Louisbourg 16 Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Park 17 St. -

EXPLORER Official Visitors Guide

eFREE 2021 Official Visitors Guide Annapolis Rxploroyal & AreaerFREE Special Edition U BEYO D OQW TITEK A Dialongue of Place & D’iversity Page 2, explorer, 2021 Official Visitors Guide Come in and browse our wonderful assortment of Mens and Ladies apparel. Peruse our wide The unique Fort Anne Heritage Tapestry, designed by Kiyoko Sago, was stitched by over 100 volunteers. selection of local and best sellers books. Fort Anne Tapestry Annapolis Royal Kentville 2 hrs. from Halifax Fort Anne’s Heritage Tapestry How Do I Get To Annapolis Royal? Exit 22 depicts 4 centuries of history in Annapolis Holly and Henry Halifax three million delicate needlepoint Royal Bainton's stitches out of 95 colours of wool. It Tannery measures about 18’ in width and 8’ Outlet 213 St George Street, Annapolis Royal, NS Yarmouth in height and was a labor of love 19025322070 www.baintons.ca over 4 years in the making. It is a Digby work of immense proportions, but Halifax Annapolis Royal is a community Yarmouth with an epic story to relate. NOVA SCOTIA Planning a Visit During COVID-19 ANNAPOLIS ROYAL IS CONVENIENTLY LOCATED Folks are looking forward to Fundy Rose Ferry in Digby 35 Minutes travelling around Nova Scotia and Halifax International Airport 120 Minutes the Maritimes. “Historic, Scenic, Kejimkujik National Park & NHS 45 Minutes Fun” Annapolis Royal makes the Phone: 9025322043, Fax: 9025327443 perfect Staycation destination. Explorer Guide on Facebook is a www.annapolisroyal.com Convenience Plus helpful resource. Despite COVID19, the area is ready to welcome visitors Gasoline & Ice in a safe and friendly environment. -

Closure of Important Parks Canada Archaeological Facility The

July 19, 2017 For Immediate Release Re: Closure of Important Parks Canada Archaeological Facility The Newfoundland and Labrador Archaeological Society is saddened to learn of Parks Canada’s continuing plans to close their Archaeology Lab in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. This purpose-built facility was just opened in 2009, specifically designed to preserve, house, and protect the archaeological artifacts from Atlantic Canada’s archaeological sites under federal jurisdiction. According to a report from the Nova Scotia Archaeological Society (NSAS), Parks Canada’s continued plans are to shutter this world-class laboratory, and ship the archaeological artifacts stored there to Gatineau, Quebec, for long-term storage. According to data released by the NSAS, the archaeological collection numbers approximately “1.45 million archaeological objects representing thousands of years of Atlantic Canadian heritage”. These include artifacts from the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, including sites at Signal Hill National Historic Site, Castle Hill National Historic Site, L’Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site, Terra Nova National Park, Gros Morne National Park, and the Torngat Mountains National Park. An archaeological collection represents more than just objects—also stored at this facility are the accompanying catalogues, site records, maps and photographs. For Immediate Release Re: Closure of Important Parks Canada Archaeological Facility This facility is used by a wide swath of heritage professionals and students. Federal and provincial heritage specialists, private heritage industry consultants, university researchers, conservators, community groups, and students of all ages have visited and made use of the centre. Indeed, the Archaeology Laboratory is more than just a state-of-the-art artifact storage facility for archaeological artifacts—its value also lies in the modern equipment housed in its laboratories, in the information held in its reference collections, site records, and book collections, and in the collective knowledge of its staff. -

A Review of Ice and Tide Observations in the Bay of Fundy

A tlantic Geology 195 A review of ice and tide observations in the Bay of Fundy ConDesplanque1 and David J. Mossman2 127 Harding Avenue, Amherst, Nova Scotia B4H 2A8, Canada departm ent of Physics, Engineering and Geoscience, Mount Allison University, 67 York Street, Sackville, New Brunswick E4L 1E6, Canada Date Received April 27, 1998 Date Accepted December 15,1998 Vigorous quasi-equilibrium conditions characterize interactions between land and sea in macrotidal regions. Ephemeral on the scale of geologic time, estuaries around the Bay of Fundy progressively infill with sediments as eustatic sea level rises, forcing fringing salt marshes to form and reform at successively higher levels. Although closely linked to a regime of tides with large amplitude and strong tidal currents, salt marshes near the Bay of Fundy rarely experience overflow. Built up to a level about 1.2 m lower than the highest astronomical tide, only very large tides are able to cover the marshes with a significant depth of water. Peak tides arrive in sets at periods of 7 months, 4.53 years and 18.03 years. Consequently, for months on end, no tidal flooding of the marshes occurs. Most salt marshes are raised to the level of the average tide of the 18-year cycle. The number of tides that can exceed a certain elevation in any given year depends on whether the three main tide-generating factors peak at the same time. Marigrams constructed for the Shubenacadie and Cornwallis river estuaries, Nova Scotia, illustrate how the estuarine tidal wave is reshaped over its course, to form bores, and varies in its sediment-carrying and erosional capacity as a result of changing water-surface gradients. -

3.6Mb PDF File

Be sure to visit all the National Parks and National Historic Sites of Canada in Nova Scotia: • Halifax Citadel National • Historic Site of Canada Prince of Wales Tower National • Historic Site of Canada York Redoubt National Historic • Site of Canada Fort McNab National Historic • Site of Canada Georges Island National • Historic Site of Canada Grand-Pré National Historic • Site of Canada Fort Edward National • Historic Site of Canada New England Planters Exhibit • • Port-Royal National Historic Kejimkujik National Park of Canada – Seaside • Site of Canada • Fort The Bank Fishery/Age of Sail Exhibit • Historic Site of Canada • Melanson SettlementAnne National Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Site National Historic Site of Canada • of Canada • Kejimkujik National Park and Marconi National Historic National Historic Site of Canada • Site of Canada Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site of • Canada Canso Islands National • Historic Site of Canada St. Peters Canal National • Historic Site of Canada Cape Breton Highlands National Park/Cabot T National Parks and National Historic rail Sites of Canada in Nova Scotia See inside for details on great things to see and do year-round in Nova Scotia including camping, hiking, interpretation activities and more! Proudly Bringing You Canada At Its Best Planning Your Visit to the National Parks and Land and culture are woven into the tapestry of Canada's history National Historic Sites of Canada and the Canadian spirit. The richness of our great country is To receive FREE trip-planning information on the celebrated in a network of protected places that allow us to National Parks and National Historic Sites of Canada understand the land, people and events that shaped Canada. -

Placenaming on Cape Breton Island 381 a Different View from The

Placenaming on Cape Breton Island A different view from the sea: placenaming on Cape Breton Island William Davey Cape Breton University Sydney NS Canada [email protected] ABSTRACT : George Story’s paper A view from the sea: Newfoundland place-naming suggests that there are other, complementary methods of collection and analysis than those used by his colleague E. R. Seary. Story examines the wealth of material found in travel accounts and the knowledge of fishers. This paper takes a different view from the sea as it considers the development of Cape Breton placenames using cartographic evidence from several influential historic maps from 1632 to 1878. The paper’s focus is on the shift names that were first given to water and coastal features and later shifted to designate settlements. As the seasonal fishing stations became permanent settlements, these new communities retained the names originally given to water and coastal features, so, for example, Glace Bay names a town and bay. By the 1870s, shift names account for a little more than 80% of the community names recorded on the Cape Breton county maps in the Atlas of the Maritime Provinces . Other patterns of naming also reflect a view from the sea. Landmarks and boundary markers appear on early maps and are consistently repeated, and perimeter naming occurs along the seacoasts, lakes, and rivers. This view from the sea is a distinctive quality of the island’s names. Keywords: Canada, Cape Breton, historical cartography, island toponymy, placenames © 2016 – Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada Introduction George Story’s paper The view from the sea: Newfoundland place-naming “suggests other complementary methods of collection and analysis” (1990, p. -

Labour Day 2011 Returns to the Gaspereau Valley Wolfville, Nova Scotia September 2 to 5, 2011

Labour Day 2011 Returns to the Gaspereau Valley Wolfville, Nova Scotia September 2 to 5, 2011 Long time members of the Maritime Organization of Rover Enthusiasts (MORE) will remember Labour Day in and around Wolfville back in 1999 and 2000. After years of resistance we, Julie and Peter Rosvall, will host Labour Day on our property once again. With the help of fellow Rover owners in our neighbourhood we will invite folks from across the Maritimes, New England, points west and internationally to our home. Kris Lockhart has been scouting and doing trail maintenance for so long already that the local joke is that by Labour Day 2011 he might have them paved if we don't watch out. All trailheads will be within 5 minutes of our property, and will have lots of options for every driving preference. Rosie Browning is taking the lead on food, after the great success of her desserts in Cape Breton. She has dreams of sandwiches made with roast beef and turkey (yes, real roast, really, cooked just prior to making the sandwiches, I'm drooling already). Rosie will be helped by a team of my relatives and our neighbours. All meals from Friday evening to Sunday night are provided on site, and the food will be amazing. I'm sure we'll have the Barr family put to work on this and other logistical details, and the Rudermans as well, and anyone else we can sucker in to volunteering leading up to the event and during. (willing volunteers can contact me using the coordinates below) Camping for the event will be on our property; tents will be setup among the cherry and pear trees, bordered by blackberry bushes. -

Minas Basin, N.S

An examination of the population characteristics, movement patterns, and recreational fishing of striped bass (Morone saxatilis) in Minas Basin, N.S. during summer 2008 Report prepared for Minas Basin Pulp and Power Co. Ltd. Contributors: Jeremy E. Broome, Anna M. Redden, Michael J. Dadswell, Don Stewart and Karen Vaudry Acadia Center for Estuarine Research Acadia University Wolfville, NS B4P 2R6 June 2009 2 Executive Summary This striped bass study was initiated because of the known presence of both Shubenacadie River origin and migrant USA striped bass in the Minas Basin, the “threatened” species COSEWIC designation, the existence of a strong recreational fishery, and the potential for impacts on the population due to the operation of in- stream tidal energy technology in the area. Striped bass were sampled from Minas Basin through angling creel census during summer 2008. In total, 574 striped bass were sampled for length, weight, scales, and tissue. In addition, 529 were tagged with individually numbered spaghetti tags. Striped bass ranged in length from 20.7-90.6cm FL, with a mean fork length of 40.5cm. Data from FL(cm) and Wt(Kg) measurements determined a weight-length relationship: LOG(Wt) = 3.30LOG(FL)-5.58. Age frequency showed a range from 1-11 years. The mean age was 4.3 years, with 75% of bass sampled being within the Age 2-4 year class. Total mortality (Z) was estimated to be 0.60. Angling effort totalling 1732 rod hours was recorded from June to October, 2008, with an average 7 anglers fishing per tide. Catch per unit effort (Fish/Rod Hour) was determined to be 0.35, with peak landing periods indicating a relationship with the lunar cycle. -

Spring 2017 Newsletter

SPRING 2017 Les Guédry et Petitpas d’Asteur Volume 15, Issue 1 GENERATIONS IN THIS ISSUE In our Spring 2017 issue of “Generations” we hope you will find several articles of in- terest. Check out the Historical Tidbits, Bon Appetit and Book Reviews as well as the CATHERINE 2 article on Catherine Bugaret and the Bugaret family in Acadia. BUGARET- ANCESTRAL The Congrès Mondial Acadien 2019 is just over two years away so we are beginning to MOTHER OF THE plan the Guédry et Petitpas Reunion. The CMA 2019 will take place between 3-24 Au- PETITPAS FAMLY gust 2019 and we would like to have the Guédry et Petitpas Reunion on Saturday, 17 ANCESTRAL August 2019. The CMA 2019 will be within two provinces of Canada – Prince Edward GRANDMOTHER OF THE GUÉDRY Island and southeastern New Brunswick. On Prince Edward Island the Evangeline FAMILY Region (North Cape Coastal Drive) on the northwestern end of PEI is the Acadian re- gion . In southeastern New Brunswick the two areas of Acadian interest are Moncton by R. Martin Guidry and the Memramcook region south of Moncton. The Memramcook area has a predomi- nantly Acadian population. We have had our past reunions in south Louisiana, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and northern Maine. For those considering attending the LEO PETTIPAS 10 MANITOBA 2019 Reunion, where would you like to meet – Prince Edward Island or New ARTICLE Brunswick? Send a brief email to [email protected] and state your choice. We’ll try to select a site for the Reunion this summer. You can get a free copy of the Prince Edward Island Visitor Guide at: https://www.tourismpei.com/pei-visitors-guide.