Neuroexistentialism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constructing Artificial Intelligence Paul Edwards, the Closed World

* c 4 1 v. N > COMPUTERS . discourse »"• "u m com *»» *l't"'tA PAUL N. EDWARDS The Closed World Inside Technology edited by Wiebe E. Bijker, W. Bernard Carlson, and Trevor Pinch Wiebe E. Bijker, Of Bicycles, Bahelites, and Bulbs: Toward a Theory of Sociotechnical Change Wiebe E. Bijker and John Law, editors, Shaping Technology/Building Society: Studies m Sociotechnical Change Stuart S. Blume, Insight and Industry: On the Dynamics of Technological Change in Medicine Louis L. Bucciarelli, Designing Engineers Geoffrey C. Bowker, Science on the Run: Information Management and Industrial Geophysics at Schlumberger, 1920-1940 H. M. Collins, Artificial Experts: Social Knowledge and Intelligent Machines Paul N. Edwards, The Closed World: Computers and the Politics of Discourse in Cold War America Pamela E. Mack, Viewing the Earth: The Social Construction of the Landsat Satellite System Donald MacKenzie, Inventing Accuracy: A Historical Sociology of Nuclear Missile Guidance Donald MacKenzie, Knowing Machines: Essays on Technical Change The Closed World Computers and the Politics of Discourse in Cold War America Paul N. Edwards The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England ©1996 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Baskerville by Pine Tree Composition, Inc. and printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Edwards, Paul N. The closed world : computers and the politics of discourse in Cold War America / Paul N. -

A Logical Calculus of the Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity*

Bulletin of Mothemnticnl Biology Vol. 52, No. l/2. pp. 99-115. 1990. oo92-824OjW$3.OO+O.MI Printed in Great Britain. Pergamon Press plc Society for Mathematical Biology A LOGICAL CALCULUS OF THE IDEAS IMMANENT IN NERVOUS ACTIVITY* n WARREN S. MCCULLOCH AND WALTER PITTS University of Illinois, College of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry at the Illinois Neuropsychiatric Institute, University of Chicago, Chicago, U.S.A. Because of the “all-or-none” character of nervous activity, neural events and the relations among them can be treated by means of propositional logic. It is found that the behavior of every net can be described in these terms, with the addition of more complicated logical means for nets containing circles; and that for any logical expression satisfying certain conditions, one can find a net behaving in the fashion it describes. It is shown that many particular choices among possible neurophysiological assumptions are equivalent, in the sense that for every net behaving under one assumption, there exists another net which behaves under the other and gives the same results, although perhaps not in the same time. Various applications of the calculus are discussed. 1. Introduction. Theoretical neurophysiology rests on certain cardinal assumptions. The nervous system is a net of neurons, each having a soma and an axon. Their adjunctions, or synapses, are always between the axon of one neuron and the soma of another. At any instant a neuron has some threshold, which excitation must exceed to initiate an impulse. This, except for the fact and the time of its occurence, is determined by the neuron, not by the excitation. -

THE INTELLECTUAL ORIGINS of the Mcculloch

JHBS—WILEY RIGHT BATCH Top of ID Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 38(1), 3–25 Winter 2002 ᭧ 2002 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. (PHYSIO)LOGICAL CIRCUITS: THE INTELLECTUAL ORIGINS OF THE Base of 1st McCULLOCH–PITTS NEURAL NETWORKS line of ART TARA H. ABRAHAM This article examines the intellectual and institutional factors that contributed to the col- laboration of neuropsychiatrist Warren McCulloch and mathematician Walter Pitts on the logic of neural networks, which culminated in their 1943 publication, “A Logical Calculus of the Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity.” Historians and scientists alike often refer to the McCulloch–Pitts paper as a landmark event in the history of cybernetics, and funda- mental to the development of cognitive science and artificial intelligence. This article seeks to bring some historical context to the McCulloch–Pitts collaboration itself, namely, their intellectual and scientific orientations and backgrounds, the key concepts that contributed to their paper, and the institutional context in which their collaboration was made. Al- though they were almost a generation apart and had dissimilar scientific backgrounds, McCulloch and Pitts had similar intellectual concerns, simultaneously motivated by issues in philosophy, neurology, and mathematics. This article demonstrates how these issues converged and found resonance in their model of neural networks. By examining the intellectual backgrounds of McCulloch and Pitts as individuals, it will be shown that besides being an important event in the history of cybernetics proper, the McCulloch– Pitts collaboration was an important result of early twentieth-century efforts to apply mathematics to neurological phenomena. ᭧ 2002 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. -

THE RISE of CYBORG CULTURE OR the BOMB WAS a CYBORG David Porush

Document generated on 09/25/2021 8 a.m. Surfaces THE RISE OF CYBORG CULTURE OR THE BOMB WAS A CYBORG David Porush SUR LA PUBLICATION ÉLECTRONIQUE Article abstract ON ELECTRONIC PUBLICATION Pictured by the author as a cybernetic rather than an atomic age, the Cold War Volume 4, 1994 is shown to be structured by the quest for a cybernetic modelling of human intelligence capable to eliminate uncertainty. The rise of the cyborg figure in URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1064963ar science fiction is brought into consideration as an illustration. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1064963ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal ISSN 1188-2492 (print) 1200-5320 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Porush, D. (1994). THE RISE OF CYBORG CULTURE OR THE BOMB WAS A CYBORG. Surfaces, 4. https://doi.org/10.7202/1064963ar Copyright © David Porush, 1994 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ THE RISE OF CYBORG CULTURE OR THE BOMB WAS A CYBORG David Porush ABSTRACT Pictured by the author as a cybernetic rather than an atomic age, the Cold War is shown to be structured by the quest for a cybernetic modelling of human intelligence capable to eliminate uncertainty. -

How Cybernetics Connects Computing, Counterculture, and Design

Walker Art Center — Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia — Exhibit Catalog — October 2015 How cybernetics connects computing, counterculture, and design Hugh Dubberly — Dubberly Design Office — [email protected] Paul Pangaro — College for Creative Studies — [email protected] “Man is always aiming to achieve some goal language, and sharing descriptions creates a society.[2] and he is always looking for new goals.” Suddenly, serious scientists were talking seriously —Gordon Pask[1] about subjectivity—about language, conversation, and ethics—and their relation to systems and to design. Serious scientists were collaborating to study Beginning in the decade before World War II and collaboration. accelerating through the war and after, scientists This turn away from the mainstream of science designed increasingly sophisticated mechanical and became a turn toward interdisciplinarity—and toward electrical systems that acted as if they had a purpose. counterculture. This work intersected other work on cognition in Two of these scientists, Heinz von Foerster and animals as well as early work on computing. What Gordon Pask, took an interest in design, even as design emerged was a new way of looking at systems—not just was absorbing the lessons of cybernetics. Another mechanical and electrical systems, but also biological member of the group, Gregory Bateson, caught the and social systems: a unifying theory of systems and attention of Stewart Brand, systems thinker, designer, their relation to their environment. This turn toward and publisher of the Whole Earth Catalog. Bateson “whole systems” and “systems thinking” became introduced Brand to von Foerster.[3] Brand’s Whole Earth known as cybernetics. Cybernetics frames the world in Catalog spawned a do-it-yourself publishing revolution, terms of systems and their goals. -

Warren S. Mcculloch: What Is a Number, That a Man May Know It, and a Man, That He May Know a Number?, In: (Winter-Edition 2008/09), J

Winter-Edition 2008/09 Warren S. McCulloch [*] What Is a Number, that a Man May Know It, and a Man, that He May Know a Number? GENTLEMEN: I am very sensible of the honor you have conferred upon me by inviting me to read this lecture. I am only distressed, fearing you may have done so under a misapprehension; for, though my interest always was to reduce epistemology to an experimental science, the. bulk of my publications has been concerned with the physics and chemistry of the brain and body of beasts. For my interest in the functional organization of the nervous system, that knowledge was as necessary as it was insufficient in all problems of communication in men and machines. I had begun to fear that the tradition of experimental epistemology I had inherited through Dusser de Barenne from Rudolph Magnus would die with me, but if you read "What the Frog's Eye Tells the Frog's Brain," written by Jerome Y. Lettvin, which appeared in the Proceedings of the Institute of Radio Engineers, November 1959, you will realize that the tradition will go on after I am gone. The inquiry into the physiological substrate of knowledge is here to stay until it is solved thoroughly, that is, until we have a satisfactory explanation of how we know what we know, stated in terms of the physics and chemistry, the anatomy and physiology, of the biological system. At the moment my age feeds on my youth – and both are unknown to you. It is not because I have reached what Oliver Wendell Holmes would call "our anecdotage" – but because all impersonal questions arise from personal reasons and are best understood from their histories – that I would begin with my youth. -

Cybernetics, Information Turn, Biocomplexity

INDIANA [email protected] Nature.com; ANDY POTTS; TURING FAMILY UNIVERSITY informatics.indiana.edu/rocha McCulloch & Pitts Memory can be maintained in circular networks of binary switches McCulloch, W. and W. Pitts [1943], "A Logical Calculus of Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity". Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics 5:115-133. A Turing machine program could be implemented in a finite network of binary neuron/switches Neurons as basic computing unit of the brain Circularity is essential for memory (closed loops to sustain memory) Brain (mental?) function as computing Others at Macy Meeting emphasized other aspects of brain activity Chemical concentrations and field effects (not digital) Ralph Gerard and Fredrik Bremmer INDIANA [email protected] UNIVERSITY informatics.indiana.edu/rocha cybernetics post-war science Synthetic approach Macy Conferences: 1946-53 Engineering-inspired Supremacy of mechanism Postwar culture of problem solving Interdisciplinary teams Cross-disciplinary methodology All can be axiomatized and computed Mculloch&Pitts’ work was major influence “A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity”. Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics 5:115-133 (1943). A Turing machine (any function) could be implemented with a network of simple binary switches (if circularity/feedback is present) Warren S. McCulloch Margaret Mead Claude Shannon INDIANA [email protected] UNIVERSITY informatics.indiana.edu/rocha cybernetics universal computers and general-purpose informatics the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation Meetings post-war science 1946-1953 Interdisciplinary Since a large class of ordinary phenomena exhibit circular causality, and mathematics is accessible, let’s look at them with a war-time team culture Participants John Von Neumann, Leonard Savage, Norbert Wiener, Arturo Rosenblueth, Walter Pitts, Margaret Mead, Heinz von Foerster, Warren McCulloch, Gregory Bateson, Claude Shannon, Ross Ashby, etc. -

Kathleen A. Powers Dissertation

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Cybernetic Origins of Life Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9d8678w5 Author Powers, Kathleen Alicia Publication Date 2020 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Cybernetic Origins of Life By Kathleen A. Powers A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Rhetoric and the Designated Emphasis in Science and Technology Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Chair Professor David Bates Professor James Porter Professor Emeritus Gaetan Micco Professor Sandra Eder Fall 2020 1 Abstract The Cybernetic Origins of Life by Kathleen A. Powers Doctor of Philosophy in Rhetoric and the Designated Emphasis in Science and Technology Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor David Bates, Chair This dissertation elucidates the cybernetic response to the life question of post-World War II biology through an analysis of the writings and experiments of Warren S. McCulloch. The work of McCulloch, who was both a clinician and neurophysiologist, gave rise to what this dissertation refers to as a biological, medical cybernetics, influenced by vitalist conceptions of the organism as well as technical conceptions of the organ, the brain. This dissertation argues that the question ‘what is biological life?’ served as an organizing principle for the electrical, digital model of the brain submitted in “Of Digital Computers Called Brains” (1949) and the formal, mathematical model of the brain required by the McCulloch-Pitts neuron in “A Logical Calculus of the Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity” (1943). -

Artificial Intelligence

INFORMATION | ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE The Man Who Tried to Redeem the World with Logic Walter Pitts rose from the streets to MIT, but couldn’t escape himself BY AMANDA GEFTER ALTER PITTS WAS USED to being bullied. in the library until he had read each volume cover to He’d been born into a tough family in cover—nearly 2,000 pages in all—and had identified W Prohibition-era Detroit, where his father, several mistakes. Deciding that Bertrand Russell him- a boiler-maker, had no trouble raising his self needed to know about these, the boy drafted a fists to get his way. The neighborhood boys weren’t letter to Russell detailing the errors. Not only did Rus- much better. One afternoon in 1935, they chased him sell write back, he was so impressed that he invited through the streets until he ducked into the local Pitts to study with him as a graduate student at Cam- library to hide. The library was familiar ground, where bridge University in England. Pitts couldn’t oblige him, he had taught himself Greek, Latin, logic, and mathe- though—he was only 12 years old. But three years later, matics—better than home, where his father insisted he when he heard that Russell would be visiting the Uni- drop out of school and go to work. Outside, the world versity of Chicago, the 15-year-old ran away from home was messy. Inside, it all made sense. and headed for Illinois. He never saw his family again. Not wanting to risk another run-in that night, Pitts In 1923, the year that Walter Pitts was born, a stayed hidden until the library closed for the eve- 25-year-old Warren McCulloch was also digesting the ning. -

Heims Steve Joshua the Cyb

The Cybernetics Group Steve Joshua Heims The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England Contents Preface Vl! Acknowledgments Xl 1 Midcentury, U.SA. 1 2 March 8-9, 1946 14 3 Describing "Embodiments of Mind": McCulloch and His Cohorts 31 4 Raindancer, Scout, and Talking Chief 52 5 Logic Clarifying and Logic Obscuring 90 6 Problems of Deranged Minds, Artists, 115 and psychiatrists " 7 The Macy Foundation and Worldwide Mental Health 164 © 1991 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any fo rm by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Baskerville by C(ompset, Inc. and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Heims, Steve J. The cybernetics group / Steve Joshua Heims. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-08200-4 1. Social sciences-Research-United States. 2. Cybernetics United States. 3. Science-Social aspects-United States. 4. Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation. I. Title. H62.5.U5H45 1991 003' .5-dc20 91-409 elP vi Cuntents 8 Lazarsfeld, Lewin, and Political Conditions 180 9 Gestalten Go to Bits, 1: From Lewin to Bavelas 201 10 Gestalten Go to Bits, 2: Kohler's Visit 224 11 Metaphor and Synthesis 248 12 Then and Now 273 Appendix Members of the Cybernetics Group 285 Notes 287 Index 327 Preface The subject of this book is the series of multidisciplinary con ferences, supported by the Macy Foundation and held between 1946 and 1953, to discuss a wide array of topics that eventually came to be called cybernetics. -

Social Studies of Science

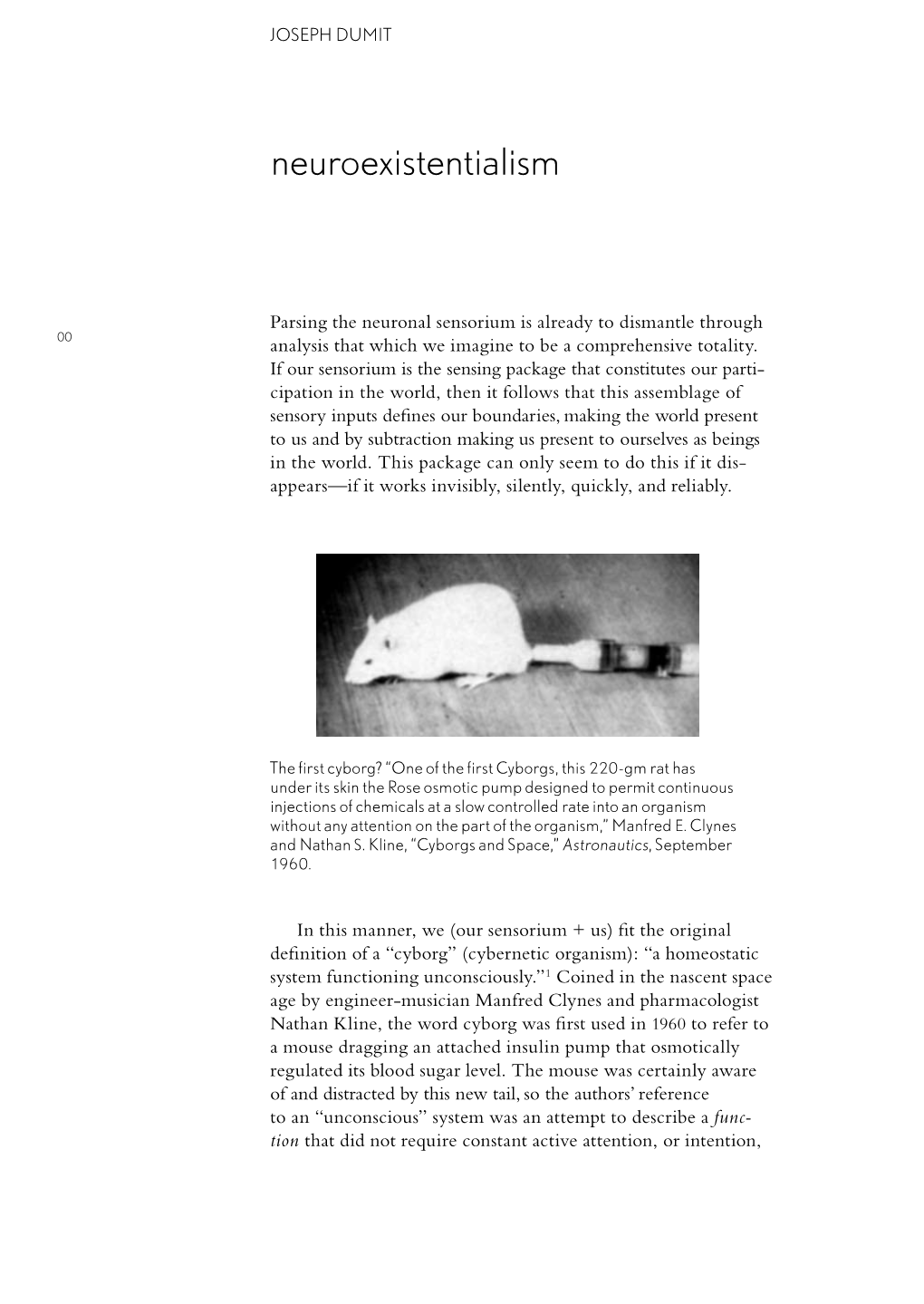

Social Studies of Science http://sss.sagepub.com/ Where are the Cyborgs in Cybernetics? Ronald Kline Social Studies of Science 2009 39: 331 DOI: 10.1177/0306312708101046 The online version of this article can be found at: http://sss.sagepub.com/content/39/3/331 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Social Studies of Science can be found at: Email Alerts: http://sss.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://sss.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://sss.sagepub.com/content/39/3/331.refs.html >> Version of Record - May 22, 2009 What is This? Downloaded from sss.sagepub.com at St Petersburg State University on January 11, 2014 ABSTRACT Cyborgs – cybernetic organisms, hybrids of humans and machines – have pervaded everyday life, the military, popular culture, and the academic world since the advent of cyborg studies in the mid 1980s. They have been a recurrent theme in STS in recent decades, but there are surprisingly few cyborgs referred to in the early history of cybernetics in the USA and Britain. In this paper, I analyze the work of the early cyberneticians who researched and built cyborgs. I then use that history of cyborgs as a basis for reinterpreting the history of cybernetics by critiquing cyborg studies that give a teleological account of cybernetics, and histories of cybernetics that view it as a unitary discipline. I argue that cyborgs were a minor research area in cybernetics, usually classified under the heading of ‘medical cybernetics’, in the USA and Britain from the publication of Wiener’s Cybernetics in 1948 to the decline of cybernetics among mainstream scientists in the 1960s. -

Warren S. Mcculloch Papers Circa 1935-1968 Mss.B.M139

Warren S. McCulloch Papers Circa 1935-1968 Mss.B.M139 American Philosophical Society 9/2000 105 South Fifth Street Philadelphia, PA, 19106 215-440-3400 [email protected] Warren S. McCulloch Papers 1860s-1987 Mss.B.M139 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Background note ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Scope & content ..........................................................................................................................................6 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................7 Indexing Terms ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................8 Series I. Correspondence......................................................................................................................... 8 Series II. Professional Papers.............................................................................................................. 108 Series III. Works by Warren S. McCulloch........................................................................................149