Harlequin Bug

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Transcriptome Survey Spanning Life Stages and Sexes of the Harlequin Bug, Murgantia Histrionica

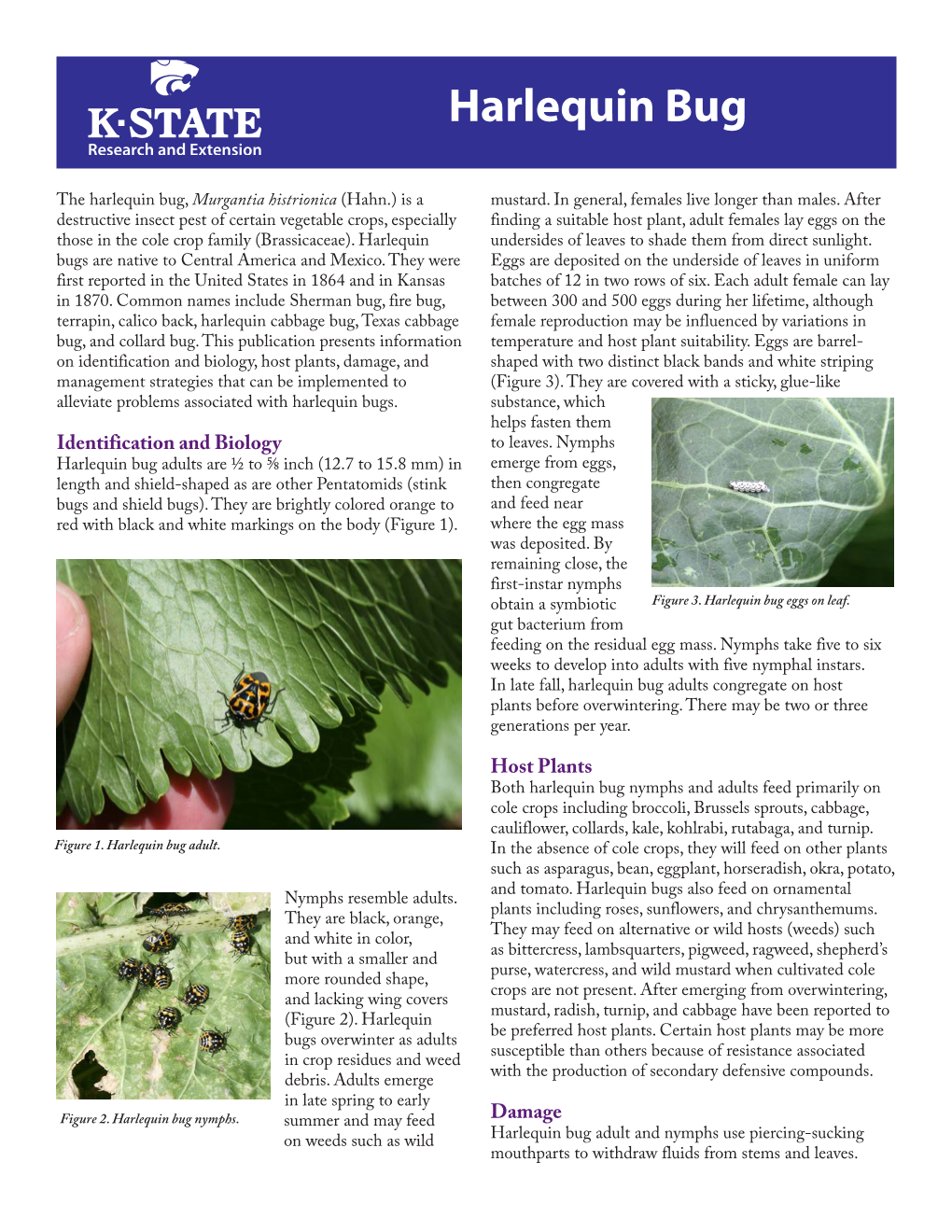

insects Article A Transcriptome Survey Spanning Life Stages and Sexes of the Harlequin Bug, Murgantia histrionica Michael E. Sparks 1, Joshua H. Rhoades 1, David R. Nelson 2, Daniel Kuhar 1, Jason Lancaster 3, Bryan Lehner 3, Dorothea Tholl 3, Donald C. Weber 1 and Dawn E. Gundersen-Rindal 1,* 1 Invasive Insect Biocontrol and Behavior Laboratory, USDA-ARS, Beltsville, MD 20705, USA; [email protected] (M.E.S.); [email protected] (J.H.R.); [email protected] (D.K.); [email protected] (D.C.W.) 2 Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Biochemistry, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, TN 38163, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Biological Sciences, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA 24061, USA; [email protected] (J.L.); [email protected] (B.L.); [email protected] (D.T.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-301-504-6692 Academic Editor: Brian T. Forschler Received: 27 March 2017; Accepted: 18 May 2017; Published: 25 May 2017 Abstract: The harlequin bug, Murgantia histrionica (Hahn), is an agricultural pest in the continental United States, particularly in southern states. Reliable gene sequence data are especially useful to the development of species-specific, environmentally friendly molecular biopesticides and effective biolures for this insect. Here, mRNAs were sampled from whole insects at the 2nd and 4th nymphal instars, as well as sexed adults, and sequenced using Illumina RNA-Seq technology. A global assembly of these data identified 72,540 putative unique transcripts bearing high levels of similarity to transcripts identified in other taxa, with over 99% of conserved single-copy orthologs among insects being detected. -

Bagrada Bug Bagrada Hilaris (Burmeister 1835)

A Consortium of Regional Networks 1 Bagrada Bug Bagrada hilaris (Burmeister 1835) Common names: bagrada bug, painted bug, painted stink bug, African stink bug 2 Bagrada Bug Distribution and Spread Distribution in Africa Western AZ around Yuma It is a major cabbage pest in Botswana, Malawi, 3 First found in LA county in 2008 Zambia and Zimbabwe. Bagrada Bug Distribution and Spread The global distribution of this pest also includes southern Asia in India, and southern Europe on Malta and Cyprus, and in Italy. 4 The Bagrada bug spreads 2011 Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec AZ x x x x x x x x x x CA x x x x x x x x x x x NV x x x NM x 5 Bagrada Bug Host Range Photo by Ettore Balocchi Crops: Brassicaceae: arugula, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, Chinese cabbage, cauliflower, collard greens, cress, horseradish, kale, mustard, radish, rapeseed (canola), rutabaga, turnips, wasabi, & watercress. Ornamentals include candytuft, Lunaria (honesty) purple rock cress, stock, sweet alyssum, & the weeds London rocket, & shepherd’s purse. Other hosts are sorghum, Sudangrass, corn, cucurbits, potato, cotton, okra, pearl millet, sugar cane, wheat, and some legumes and those yet to be observed in the western hemisphere 6 Bagrada Bug Female Male 7 Relative Size of the Bagrada Bug Size comparison of Bagrada bugs and Convergent Lady Beetles Photo courtesy of: Bagrada Bug Lifespan The bugs are often seen in characteristic mating pairs, moving around attached end-to-end. The adults lay 100 or more eggs on the foliage or soil. -

Building of the Us Department of Agriculture

MAIN BUILDING OF THE U. S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE. YEARBOOK Olf THK UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE. 1895. WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 4 1896. [PUBLIC—No. 15.] An act providing for the public printing and binding and the distribution of public documents, * * ## * if * Section 17, paragraph 2 : The Annual Report of the Secretary of Agriculture shall hereafter be submitted and printed in two parts, as follows : Part one, which shall contain purely busi- ness and executive matter which it is necessary for the Secretary to submit to the President and Congress; part two, which shall contain such reports from the different buïeaus and divisions, and such papers prepared by their special agents, accompanied by suitable illustrations, as shall, in the opinion of the Secretary, be specially suited to interest and instruct the farmers of the country, and to include a general report of the operations of the Department for their information. There shall be printed of part one, one thousand copies for the Senate, two thou- sand copies for the House, and three thousand copies for the Department of Agri- culture ; and of part two, one hundred and ten thousand copies for the use of the Senate, three hundred and sixty thousand copies for the use of the House of Rep- resentatives, and thirty thousand copies for the use of the Department of Agri- culture, tho illustrations for the same to be executed under the supervision of the Public Printer, in accordance with directions of the Joint Committee on Printing, said illustrations to be subject to the approval of the Secretary of Agriculture; and the title of each of the said parts shall be such as to show that such part is complete in itself. -

Bagrada Bug Bagrada Hilaris (Burmeister 1835)

Bagrada Bug Bagrada hilaris (Burmeister 1835) Common names: bagrada bug, painted bug, painted stink bug, African stink bug 1 Bagrada Bug Female Male 2 Bagrada Bugs are Prolific Photo by Gevork Arakelian Photo by Ron Hemberger 3 Bagrada Bug Distribution and Spread Distribution in Africa Western AZ around Yuma It is a major cabbage pest in Botswana, Malawi, 4 First found in LA county in 2008 Zambia and Zimbabwe. Photo by Delbert Crawford 5 Relative Size of the Bagrada Bug Size comparison of Bagrada bugs and Convergent Lady Beetles ¼” or 6-8 mm Photo courtesy of: The Bagrada bug spreads 7 Bagrada Bug Spreading in CA 8 Bagrada Bug Host Range Photo by Ettore Balocchi Crops: Brassicaceae: arugula, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, Chinese cabbage, cauliflower, collard greens, cress, horseradish, kale, mustard, radish, rapeseed (canola), rutabaga, turnips, wasabi, & watercress. Ornamentals include candytuft, Lunaria (honesty) purple rock cress, stock, sweet alyssum, & the weeds London rocket, & shepherd’s purse. Other hosts are sorghum, Sudangrass, corn, cucurbits, potato, cotton, okra, pearl millet, sugar cane, wheat, and some legumes and those yet to be observed in the western hemisphere 9 10 Life stages of the Bagrada Bug Adults are 5-7 mm ( ¼ inch) in length Photos courtesy of F. Haas, icipe Photo courtesy of Elliotte Rusty Harold 11 Look alike: The Harlequin Bug Murgantia histrionica (Hahn 1834) Photos courtesy of Ron Hemberger The Harlequin bug spread from Mexico into the southern US around the time of the Civil War. It also feeds on members of the Brassicaceae family. 12 The Harlequin Bug The harlequin cabbage bug ,also known as calico bug, fire bug or harlequin bug, is a black stinkbug of the family Pentatomidae, brilliantly marked with red, orange and yellow. -

Native Vegetation to Enhance Biodiversity, Beneficial Insects and Pest Control in Horticulture Systems

Phase II: Native vegetation to enhance biodiversity, beneficial insects and pest control in horticulture systems Dr Nancy Schellhorn CSIRO Entomology Project Number: VG06024 VG06024 This report is published by Horticulture Australia Ltd to pass on information concerning horticultural research and development undertaken for the vegetables industry. The research contained in this report was funded by Horticulture Australia Ltd with the financial support of the vegetable industry. All expressions of opinion are not to be regarded as expressing the opinion of Horticulture Australia Ltd or any authority of the Australian Government. The Company and the Australian Government accept no responsibility for any of the opinions or the accuracy of the information contained in this report and readers should rely upon their own enquiries in making decisions concerning their own interests. ISBN 0 7341 1812 0 Published and distributed by: Horticulture Australia Ltd Level 7 179 Elizabeth Street Sydney NSW 2000 Telephone: (02) 8295 2300 Fax: (02) 8295 2399 E-Mail: [email protected] © Copyright 2008 HAL Project VG06024 Project Leader: Dr. Nancy A. Schellhorn CSIRO Entomology 120 Meiers Road Indooroopilly, QLD 4068 Ph: 07 3214 2721 Fx: 07 3214 2881 [email protected] Portfolio Manager: Mr. Brad Wells Portfolio Manager - Plant Health Horticulture Australia Limited Level 1, 50 Carrington Street Sydney NSW 2155 Ph: 02-8295 2327 Fax: 02-8295 2399 Mob: 0412-528 398 Email: [email protected] Web site: www.horticulture.com.au This is the final report for VG06024 titled ‘Phase II: Native vegetation to enhance biodiversity, beneficial insects and pest control in horticulture systems’ which summarised the key findings and outlines plans for future research and industry adoption of integrating native vegetation in vegetable systems. -

Harlequin Bug Biology and Pest Management in Brassicaceous Crops

Harlequin Bug Biology and Pest Management in Brassicaceous Crops 1,2 1 3 4 A. K. Wallingford, T. P. Kuhar, P. B. Schultz, AND J. H. Freeman 1Virginia Tech, Department of Entomology, 216 Price Hall, Blacksburg, VA 24061-0319. 2Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected]. 3Virginia Tech, Hampton Roads Agriculture Research and Extension Center, 1444 Diamond Springs Road, Virginia Beach, VA 23455. 4Virginia Tech, Eastern Shore Agriculture Research and Extension Center, 33446 Research Drive, Painter, VA 23420. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article-abstract/2/1/H1/2194020 by University Libraries | Virginia Tech user on 17 May 2019 J. Integ. Pest Mngmt. 2(1): 2011; DOI: 10.1603/IPM10015 ABSTRACT. Harlequin bug, Murgantia histrionica (Hahn), is a piercing-sucking pest of brassicaceous crops, particularly in the southern United States. The pest typically completes two to four generations per year, and overwinters as an adult in debris and weeds. Both adults and nymphs feed on aboveground plant tissues, leaving white blotches on leaves. Under heavy feeding pressure, plants can wilt and die. Chemical insecticides such as pyrethroids, organophosphates, carbamates, and neonicotinoids have been used for effective control of harlequin bug adults and nymphs. However, there is potential for cultural control of this pest using trap cropping. This paper reviews the biology and management of harlequin bug. Key Words: Murgantia histrionica; harlequin bug; cole crops; trap cropping Harlequin bug, Murgantia histrionica (Hahn) (Hemiptera: Pentatomi- son 2004a, McLeod 2005, Walgenbach and Schoof 2005, Kuhar and dae), is a conspicuous and important pest of cole crops (Brassicaceae), Doughty 2009). particularly in the southern United States. -

Knowledge Brokering in Biosecurity: How International Linkages and Learnings Can Help Us Build a Better System

Knowledge brokering in biosecurity: How international linkages and learnings can help us build a better system Jessica Lye (2017) Supported by the AgriFutures Rural Women’s Award and the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources Stronger Biosecurity and Quarantine Initiative (SBQI). About the author Dr Jessica Lye GAICD leads the Science & Extension project team at AUSVEG Ltd., Peak Industry Body for Australian vegetable and potato growers. Areas of expertise include plant biosecurity policy, exotic pest incursion response, agricultural engagement and extension, science communication, and promotion of agricultural innovation and practice change. Jessica is currently a member of the Australian Institute of Company Directors and the Australian Women in Agriculture. In 2016, Jessica received the AgriFutures Australia Rural Women’s Award (Victoria), an award that identifies and supports emerging leaders who have the desire, commitment and leadership potential to make a greater contribution to primary industries and rural communities. Jessica currently leads several industry levy funded projects encompassing agrichemical needs and priorities, sustainable farming, exotic plant pest management, plant pest surveillance, and farm biosecurity. She is the industry representative on the Consultative Committee for Emergency Plant Pests, and sits on multiple committees, including the Commonwealth Imported Seed Regulation Working Group (Department of Agriculture & Water Resources), and the Farm Productivity and Resource Use Strategic Investment -

H-259: Harlequin

COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURAL, CONSUMER AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES Harlequin Bug J. Breen Pierce1 aces.nmsu.edu/pubs • Cooperative Extension Service • Guide H-259 DESCRIPTION Harlequin bug (Murgantia The College of histrionica) is entomologically Agricultural, a “true” bug—an insect in the Consumer and Hemiptera or- der, which also includes stink Environmental bugs and leaf footed bugs. Sciences is an Many people in- correctly refer to engine for economic them as beetles, but beetles have a hard, protective and community covering or elytra that completely development in New covers their abdo- Figure 1. Harlequin bug development: eggs (top), nymphs men. Hemipteran (bottom left), and adult (bottom right). (Illustration by Mexico, improving insects have hem- Darren Huff, New Mexico State University.) elytra that cover only the upper abdomen. Hemipterans also have incomplete metamorphosis the lives of New (egg, nymph, and adult stages; Figure 1), while beetles have complete meta- morphosis (egg, larva, pupa, and adult stages). The presence of nymphs, Mexicans through which look similar to adults rather than larvae, indicates that these insects are not beetles. academic, research, Harlequin bug originated in Mexico and Central America but was first reported in the United States in Texas in 1864. It is considered a common pest in the southern United States but is becoming increasingly common in and Extension more northern states such as Pennsylvania, where harlequin bug was recently reported as a pest. Adults are 1/4- to 3/8-inch-long, shield-shaped insects programs. with broad shoulders. Adults and nymphs are vividly colored with deep blue or black and bright orange or red (Figures 2 and 3). -

Supercooling Points of Murgantia Histrionica (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) and Field Mortality in the Mid-Atlantic United States Following Lethal Low Temperatures

Environmental Entomology, 45(5), 2016, 1294–1299 doi: 10.1093/ee/nvw091 Advance Access Publication Date: 6 August 2016 Physiological Ecology Research Supercooling Points of Murgantia histrionica (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) and Field Mortality in the Mid-Atlantic United States Following Lethal Low Temperatures Anthony S. DiMeglio,1,2 Anna K. Wallingford,3 Donald C. Weber,4 Thomas P. Kuhar,1 and Donald Mullins1 1Department of Entomology, Virginia Tech, 170 Drillfield Drive, Blacksburg, VA 24061 ([email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]), 2Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected], 3Department of Entomology, Cornell University, 630 W. North St., Geneva, NY 14456 ([email protected]), and 4Invasive Insect Biocontrol and Behavior Lab, USDA Agricultural Research Service, BARC-West 007, Beltsville, MD 20705 ([email protected]) Received 24 April 2016; Accepted 28 June 2016 Abstract The harlequin bug, Murgantia histrionica (Hahn), is a serious pest of brassicaceous vegetables in southern North America. While this insect is limited in its northern range of North America, presumably by severe cold winter temperatures, specific information on its cold hardiness remains unknown. We determined the super- cooling points (SCPs) for Maryland and Virginia adult populations and found no significant difference among these populations. SCPs were similar for adults (X ¼10.35 C; rX ¼ 2.54) and early and late instar (X ¼11.00 C; rX ¼ 4.92) and between adult males and females. However, SCPs for first instars (X ¼21.56 C; rX ¼1.47) and eggs (X ¼23.24 C; rX ¼1.00) were significantly lower. We also evaluated field survival of overwintering harlequin bug adults during extreme cold episodes of January 2014 and January 2015, which produced widespread air temperatures lower than À15 C and subfreezing soil temperatures in the Mid-Atlantic Region. -

Harlequin Bug, Murgantia Histrionica (Hahn) (Insecta: Hemiptera: Pentatomidae)1 M

EENY-025 Harlequin Bug, Murgantia histrionica (Hahn) (Insecta: Hemiptera: Pentatomidae)1 M. A. Knox2 Introduction of the leaves of the host plant. Each egg is marked by two broad black “hoops” and a black spot. The eggs hatch in The harlequin bug is an important insect pest of cabbage four to 29 days, the time varying with the temperature. and related crops in the southern half of the United States. This pest has the ability to destroy the entire crop where it is not controlled. The harlequin bug injures the host plants by sucking the sap of the plants, causing the plants to wilt, brown, and die. Distribution The harlequin bug is a southern insect ranging from the Atlantic to the Pacific coasts. This insect is rarely found north of Colorado and Pennsylvania. It first spread over the southern United States from Mexico shortly after the Civil War. Figure 1. Eggs of the harlequin bug, Murgantia histrionica (Hahn). Credits: James Castner, UF/IFAS Description and Life Cycle Nymphs A generation of the harlequin bug requires 50 to 80 days. There are five or six nymphal instars that feed and grow for The life cycle consists of three stages: egg, nymph, and four to nine weeks before they are capable of mating. The adult. Harlequin bugs pass the winter as adults (which are head coloration of the nymphs ranges from pale orange (in commonly referred to by laypeople as stink bugs) and true the first instar) and dark orange (in the second to fourth) hibernation is doubtful. to black (in the fifth instar). -

APPENDIX 2-4: OPPIN Bibliography for Malathion (PDF)

Bibliography MRID Citation Reference 1249 Smith, C.N.; Roos, J. (1965) Results of Tests with American Cyanamid 52,160 from American Cyanamid Company. (Unpublished study received May 27, 1965 under 241-132; prepared by U.S. Agricultural Research Service, Entomology Research Div., Insects Affecting Man and Animals Research Branch, submitted by American Cyanamid Co., Princeton, N.J.; CDL:001791-AJ) 1254 American Cyanamid Company (1969) Modern Mosquito Control with Abate ^(R)I Mosquito Larvicide and Insecticide and Cythion ^(R)I Insecticide, the Premium Grade Malathion. (Unpublished study received 1969 under unknown admin. no.; CDL:128976-A) 1310 Cole, M.M.; Hirst, J.M.; McWilliams, J.G.; Gilbert, I.H. (1969) Sleeve tests of insecticidal powders for control of body lice. Journal of Economic Entomology 62(1):198-200. (Also~In~unpub- lished submission received Sep 1, 1972 under 241-230; submitted by American Cyanamid Co., Princeton, N.J.; CDL: 002063-I) 1311 Hirst, J.M.; Cole, M.M.; Gilbert, I.H.; Adams, C.T. (1970) Further sleeve tests of new powders for control of body lice. Journal of Economic Entomology 63(3):861-862. (Also~In~unpublished submission received Sep 1, 1972 under 241-230; submitted by American Cyanamid Co., Princeton, N.J.; CDL:002063-J) 1312 Cole M.M.; Hirst, J.M.; Gilbert, I.H.; Adams, C.T. (1971) Sleeve tests of insecticides for control of body lice in 1969-70. Journal of Economic Entomology 64(3):761-762. (Also~In~unpub- lished submission received Sep 1, 1972 under 241-230; submitted by American Cyanamid Co., Princeton, N.J.; CDL:002063-K) 1313 Steinberg, M.; Cole, M.M.; Miller, T.A.; Godke, R.A. -

Anthony Stephen Dimeglio Thesis Submitted to The

Title: Murgantia histrionica (Hahn): new trapping tactics and insights on overwintering survival Name: Anthony Stephen DiMeglio Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Life Sciences In Entomology Thomas P. Kuhar, Chair Donald C. Weber, Co-Chair Dorothea Tholl September 12, 2018 Keywords: (Harlequin bug, Stink bug, Brassica, Trap, Aggregation pheromone, Murgantiol, Low temperature biology, pest management) Title Murgantia histrionica (Hahn): new trapping tactics and insights on overwintering survival ABSTRACT The harlequin bug, Murgantia histrionica (Hahn), is a serious pest of brassicaceous vegetables in southern North America, with limited establishment north of the 40°N latitude presumably due to low overwintering survival. Integrated Pest Management (IPM) requires knowledge of pest populations and tools to monitor them. For harlequin bug, knowledge of the number of successfully overwintered bugs, and development of an effective trap to monitor populations, are essential to its management. To gain insight into overwintering survival, I determined the supercooling points (SCPs) for Maryland and Virginia adult populations and found no significant difference between these populations. SCPs were similar for adults (푋̅ = -10.4oC; nd rd th th o 휎푋 = 2.5) and early (2 – 3 ) and late (4 – 5 ) instar nymphs (푋̅ = -11.0 C; 휎푋 = 4.9) and between st o adult males and females. However, SCPs for 1 instars (푋̅ = -21.6 C; 휎푋 = 1.5) and eggs (푋̅ = o -23.2 C; 휎푋 = 1.0) were significantly lower. Field survival of overwintering harlequin bug adults was significantly impacted (with 80-96% mortality) during widespread air temperatures lower than -15oC and sub-freezing soil temperatures in the mid-Atlantic region.