Northamptonshire Past and Present, No 70

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notice of Uncontested Elections

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION West Northamptonshire Council Election of Parish Councillors for Arthingworth on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Anna Earnshaw, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Arthingworth. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) HANDY 5 Sunnybank, Kelmarsh Road, Susan Jill Arthingworth, LE16 8JX HARRIS 8 Kelmarsh Road, Arthingworth, John Market Harborough, Leics, LE16 8JZ KENNEDY Middle Cottage, Oxendon Road, Bernadette Arthingworth, LE16 8LA KENNEDY (address in West Michael Peter Northamptonshire) MORSE Lodge Farm, Desborough Rd, Kate Louise Braybrooke, Market Harborough, Leicestershire, LE16 8LF SANDERSON 2 Hall Close, Arthingworth, Market Lesley Ann Harborough, Leics, LE16 8JS Dated Thursday 8 April 2021 Anna Earnshaw Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Civic Offices, Lodge Road, Daventry, Northants, NN11 4FP NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION West Northamptonshire Council Election of Parish Councillors for Badby on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Anna Earnshaw, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Badby. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BERRY (address in West Sue Northamptonshire) CHANDLER (address in West Steve Northamptonshire) COLLINS (address in West Peter Frederick Northamptonshire) GRIFFITHS (address in West Katie Jane Northamptonshire) HIND Rosewood Cottage, Church -

The 150Th Anniversary of the Royal Hospital for Neuro-Disability, Putney

426 HISTORY OF MEDICINE Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.2003.017350 on 14 July 2004. Downloaded from Caring for ‘‘incurables’’: the 150th anniversary of the Royal Hospital for Neuro-Disability, Putney G C Cook ............................................................................................................................... Postgrad Med J 2004;80:426–430. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2003.017673 The Royal Hospital for Incurables (RHI), now known as the care of these unfortunate individuals. This fact had been made clear in Household Words in 1850. Royal Hospital for Neuro-Disability and situated on West This weekly journal, with Charles Dickens Hill, Putney, was founded by Andrew Reed DD exactly 150 (1812–70) as its editor, considered: years ago. The RHI was thus the pioneer in modern times of long stay institutions for the sick and dying. It became one ‘‘It is an extraordinary fact that among of the great Victorian charities, and remained independent innumerable medical charities with which this country abounds, there is not one for the help of the National Health Service, which was introduced in of those who of all others [that is, the 1948. Originally the long stay patients suffered from a ‘‘incurables’’] most require succour …’’. multiplicity of diseases; in recent years chronic neurological disease has dominated the scenario. This institution has It is probable that Dickens was merely reflect- ing (as he often did) the popular opinion of the also become a major centre for genetic and trauma- time. In any event, Dickens took a keen interest associated neurological damage, and rehabilitation. in Reed’s initiative and presided at the first two ........................................................................... charity dinners, the prime object of which was to raise much needed funds for this unique venture. -

St Botolph's Church

ST BOTOLPH’S CHURCH BARTON SEAGRAVE ANNUAL REPORT 2017 – 2018 (Registered Charity Number 1130426) PRESENTED TO THE ANNUAL PAROCHIAL CHURCH MEETING 16th April 2018 This page has no content St Botolph’s Church St. Botolph's Church Annual Parochial Church Meeting 16th April 2018 Contents Page Agenda for Annual Parochial Church Meeting ................................. A-1 Minutes of St Botolph’s Vestry Meeting ............................................... 1 Minutes of St Botolph’s Annual Parochial Church Meeting ................. 3 1. Rector’s Report 2017 .................................................................... 7 2. St Botolph’s Church Sidespersons 2017 ...................................... 9 3. Kettering Deanery Synod Report 2017 ...................................... 10 4. St. Botolph's PCC Annual Report 2017 ...................................... 12 5. St. Botolph's Accounts 2017 ...................................................... 13 6. Churchwardens’ Report 2017 ..................................................... 21 7. Annual Fabric Report 2017 ......................................................... 22 8. Finance Group Report 2017 ........................................................ 23 9. Children’s & Youth Ministry 2017 ............................................... 24 10. Missions Task Group Report 2017 ............................................. 28 11. Evangelism 2017 ......................................................................... 29 12. Lay Pastoral Ministers’ Report 2017 ......................................... -

68 Upper Harlestone, Northampton, NN7 4EH £700,000 Freehold a Stunning Four Bedroom Detached Cottage with a Thatched Roof Located in This Popular Village Location

68 Upper Harlestone, Northampton, NN7 4EH £700,000 Freehold A stunning four bedroom detached cottage with a thatched roof located in this popular village location. The property benefits from a large garden and countryside views. The accommodation comprises: Entrance hall, sitting room, dining room, family room, kitchen/breakfast room, utility room, wc, master bedroom with en suite, three further bedrooms, bathroom, garden, off road parking and a detached double garage. ENTRANCE PORCH Double glazed windows to front and side elevations, fitted wardrobes, Door to. radiator. ENTRANCE HALL BEDROOM THREE Stairs rising to first floor landing. Double glazed window to front elevation, radiator. SITTING ROOM BEDROOM FOUR Double glazed French Doors to side elevation giving access to the rear Double glazed window to side elevation, radiator. garden, double glazed windows to side and front elevations. Feature fireplace, two radiator and TV point, double doors to dining room. BATHROOM Double glazed window to side elevation, fitted in a three piece suite to DINING ROOM comprise low level wc, wash hand basin and bath with shower over. Double glazed window to rear elevation, radiator and door to Family Room. GARDEN FAMILY ROOM This landscaped large garden is mainly laid to lawn with shrub borders. Double glazed French Doors to rear elevation giving access to rear garden, There are also two patio areas which provide space for outside double glazed windows to side and rear elevations, radiator. entertaining. KITCHEN/BREAKFAST ROOM DOUBLE GARAGE Double glazed windows to side and rear elevations, fitted in a range of Off road parking leading to double garage. base units with granite work surface over and inset sink with mixer tap over. -

Premises, Sites Etc Within 30 Miles of Harrington Museum Used for Military Purposes in the 20Th Century

Premises, Sites etc within 30 miles of Harrington Museum used for Military Purposes in the 20th Century The following listing attempts to identify those premises and sites that were used for military purposes during the 20th Century. The listing is very much a works in progress document so if you are aware of any other sites or premises within 30 miles of Harrington, Northamptonshire, then we would very much appreciate receiving details of them. Similarly if you spot any errors, or have further information on those premises/sites that are listed then we would be pleased to hear from you. Please use the reporting sheets at the end of this document and send or email to the Carpetbagger Aviation Museum, Sunnyvale Farm, Harrington, Northampton, NN6 9PF, [email protected] We hope that you find this document of interest. Village/ Town Name of Location / Address Distance to Period used Use Premises Museum Abthorpe SP 646 464 34.8 km World War 2 ANTI AIRCRAFT SEARCHLIGHT BATTERY Northamptonshire The site of a World War II searchlight battery. The site is known to have had a generator and Nissen huts. It was probably constructed between 1939 and 1945 but the site had been destroyed by the time of the Defence of Britain survey. Ailsworth Manor House Cambridgeshire World War 2 HOME GUARD STORE A Company of the 2nd (Peterborough) Battalion Northamptonshire Home Guard used two rooms and a cellar for a company store at the Manor House at Ailsworth Alconbury RAF Alconbury TL 211 767 44.3 km 1938 - 1995 AIRFIELD Huntingdonshire It was previously named 'RAF Abbots Ripton' from 1938 to 9 September 1942 while under RAF Bomber Command control. -

Records Ofearfvq English Drama

1980 :1 A newsletter published by University of Toronto Press in association with Erindale College, University of Toronto and Manchester University Press . JoAnna Dutka, editor Records ofEarfvq English Drama In this issue are Ian Lancashire's biennial bibliography of books and articles on records of drama and minstrelsy, and A .F. Johnston's list of errata and disputed readings of names in the York volumes. IAN LANCASHIRE Annotated bibliography of printed records of early British drama and minstrelsy for 1978-9 This list includes publications up to 1980 that concern records of performers and performance, but it does not notice material treating play-texts or music as such, and general or unannotated bibliographies . Works on musical, antiquarian, local, and even archaeological history figure as large here as those on theatre history . The format of this biennial bibliography is similar to that of Harrison T . Meserole's computerized Shakespeare bibliography. Literary journal titles are abbreviated as they appear in the annual MLA bibliography . My annotations are not intended to be evaluative ; they aim to abstract concisely records information or arguments and tend to be fuller for items presenting fresh evidence than for items analyzing already published records . I have tried to render faithfully the essentials of each publica- tion, but at times I will have missed the point or misstated it: for these errors I ask the indulgence of both author and user . Inevitably I will also have failed to notice some relevant publications, for interesting information is to be found in the most unlikely titles; my search could not be complete, and I was limited practically in the materials available to me up to January 1980. -

Spratton Parish Council Held on Tuesday 17Th June 2014 in the Village Hall, School Road, Spratton at 7.30 Pm

Chairman: Councillor Barry Frenchman Clerk: Mrs L Compton 12 Olde Forde Close Brixworth Northants NN6 9XF Tel/Fax 01604-880727 Email: sprattonpc@tiscali co.uk Minutes of a Meeting of Spratton Parish Council Held on Tuesday 17th June 2014 in the Village Hall, School Road, Spratton at 7.30 pm Present: Cllrs Barry Frenchman (Chairman), Tim Forster (Vice-Chairman), John Hunt, Fiona Keable, Rachel Baillie, Michael Heaton and Jay Tindale – 7 members In attendance: 3 members of the public 21.14 PUBLIC FORUM Members of the public and press are invited to address the Council at its Open Forum from 7.30 pm to 7.45 pm There were 3 members of the public in attendance who were awaiting the update on the Neighbourhood Plan. 22.14 RESOLUTION TO APPROVE APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE Cllr Frenchman proposed acceptance of apologies from Cllr Blowfield, Cllr Ruaraidh-McDonald Walker and Cllr Pacey, seconded by Cllr Heaton and resolved to be approved by Parish Council. 23.14 RESOLUTION TO SIGN AND APPROVE MINUTES OF THE ANNUAL MEETING OF PARISH COUNCIL HELD ON TUESDAY 4TH JUNE 2014 (previously circulated) – Cllr Frenchman proposed approval of the minutes, seconded by Cllr Heaton and resolved to be approved by Parish Council. 24.14 MATTERS ARISING FROM PREVIOUS MINUTES AND CLERK UPDATE REPORT (if any) – For Information only a) First Responders (209.13 b April Minutes) – to receive an update from Cllr Baillie – after some discussion and clarification that First Responders is part of the Ambulance Service and involves training people to be respond to 999 calls and not the same as the free HeartStart training which is a free 2 hour Emergency First Aid Course, Cllrs Baillie and Keable kindly agreed to look into both further and report back. -

Capability Brown at Castle Ashby

Capability Brown at Castle Ashby Capability Brown Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown (1716-1783) was born in the Northumberland village of Kirkharle, and went on to popularise the English landscape style, advising on over 250 large country estates throughout England and Wales. Formal gardens gave way to naturalistic parkland of trees, expanses of water and rolling grass. He also designed great houses, churches and garden buildings, and was skilled in engineering, especially with water. This guide was created as part of a festival celebrating the 300th Aerial view of the landscape at Castle Ashby © Northamptonshire Gardens Trust anniversary of his birth. Find out more about the man and his work In 1760 Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown prepared a ‘great General Plan’ for the at capabilitybrown.org/ parkland at Castle Ashby for Charles, 7th Earl of Northampton. He signed research a contract for work to start on the 10,000 acre estate, but he and his wife Portrait of Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, died in Italy in 1763, so never saw the work completed. c.1770-75, by Richard Cosway (17421821)/Private Collection/ The estate has been in the Compton family since 1512. In 1574 Henry Compton Bridgeman Images. built the fine Elizabethan house in the shape of an E to celebrate the coronation of Queen Elizabeth I. Brown’s work included restoring the south avenue of trees and re-levelling the ground around the house to improve the views He carefully selected, planted and felled trees to create vistas towards the Temple Menagerie, the new Park Pond. A curving ha-ha (sunken wall and ditch) was created to protect the pleasure garden from grazing animals, the fishponds were made into lakes, with a dam and cascade, and a serpentine carriage drive crossed them to create an impressive approach to the house. -

The Praetorium of Edmund Artis: a Summary of Excavations and Surveys of the Palatial Roman Structure at Castor, Cambridgeshire 1828–2010 by STEPHEN G

Britannia 42 (2011), 23–112 doi:10.1017/S0068113X11000614 The Praetorium of Edmund Artis: A Summary of Excavations and Surveys of the Palatial Roman Structure at Castor, Cambridgeshire 1828–2010 By STEPHEN G. UPEX With contributions by ADRIAN CHALLANDS, JACKIE HALL, RALPH JACKSON, DAVID PEACOCK and FELICITY C. WILD ABSTRACT Antiquarian and modern excavations at Castor, Cambs., have been taking place since the seventeenth century. The site, which lies under the modern village, has been variously described as a Roman villa, a guild centre and a palace, while Edmund Artis working in the 1820s termed it the ‘Praetorium’. The Roman buildings covered an area of 3.77 ha (9.4 acres) and appear to have had two main phases, the latter of which formed a single unified structure some 130 by 90 m. This article attempts to draw together all of the previous work at the site and provide a comprehensive plan, a set of suggested dates, and options on how the remains could be interpreted. INTRODUCTION his article provides a summary of various excavations and surveys of a large group of Roman buildings found beneath Castor village, Cambs. (centred on TL 124 984). The village of Castor T lies 8 km to the west of Peterborough (FIG. 1) and rises on a slope above the first terrace gravel soils of the River Nene to the south. The underlying geology is mixed, with the lower part of the village (8 m AOD) sitting on both terrace gravel and Lower Lincolnshire limestone, while further up the valley side the Upper Estuarine Series and Blisworth Limestone are encountered, with a capping of Blisworth Clay at the top of the slope (23 m AOD).1 The slope of the ground on which the Roman buildings have been arranged has not been emphasised enough or even mentioned in earlier accounts of the site.2 The current evidence suggests that substantial Roman terracing and the construction of revetment or retaining walls was required to consolidate the underlying geology. -

Application to Vary Approved Restoration Details

APPLICATION TO VARY APPROVED RESTORATION DETAILS HARLESTONE QUARRY JULY 2020 Revised restoration scheme - Harlestone Quarry, Northamptonshire BLANK Revised restoration scheme - Harlestone Quarry, Northamptonshire Contents 1 Introduction and Background to Proposal 1 1.1 Purpose of this Report 1 1.2 The Applicant 1 1.3 Planning and Site History 1 2 Site Location and Setting 3 3 The Development Proposals 4 4 Planning Policy 6 4.1 Introduction 6 4.2 The Development Plan 6 4.3 Other Policy Considerations 11 5 Need 13 6 Main Environmental Considerations 14 6.2 Landscape and Visual Considerations 14 6.3 Nature Conservation and Ecology 15 6.4 The Impact on Water Resources and Flood Risk 16 6.5 Soils and Agricultural Land Classification 16 7 Conclusions 17 Drawings HARL-01c – Harlestone Restoration Appendices Harlestone Quarry – Phase 2 Grassland Restoration and Aftercare Scheme Revised restoration scheme - Harlestone Quarry, Northamptonshire 1 Introduction and Background to Proposal 1.1 Purpose of this Report This document is the Planning Statement, prepared on behalf of Peter Bennie Ltd (The Applicant), which accompanies a planning application under Section 73 of the Town and Country Planning Act to vary condition 28 of planning permission reference 15/00095/MINVOC at Harlestone Quarry, Northamptonshire. Condition 28 limits restoration of the site to forestry and the Applicant is seeking to vary the restoration objectives to agricultural grassland. This Statement accompanies the planning application, outlines the proposals, and considers the potential for environmental impacts as a result of the development in accordance with the relevant Planning Policy objectives. The Application is accompanied by a restoration strategy and aftercare scheme (appendix 1) 1.2 The Applicant The Bennie Group business was founded in the 1930s and has evolved into a Group of companies operating in the orthopaedic footwear, construction and MH equipment industries. -

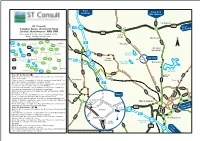

Southern Testing Location Map (Northampton)

From Leicester From A14 Mkt Harboro Harrington ST Consult A5199 A508 A14 M6 J19 J1 From Twigden Barns, Brixworth Road Kettering Creaton, Northampton NN6 8NN A5 A14 Tel: 01604 500020 - Fax: 01604 500021 Cold Email: [email protected] Ashby www.stconsult.co.uk A5199 Maidwell N A43 A508 A14 M6 Kettering Thrapston M1 J19 A14 Thornby A14 W e Rugby l A5199 fo Creaton rd Hanging J18 A43 A6 A45 R o a M45 A428 d Houghton J17 A508 Wellingborough J18 Hollowell A45 A428 Rushden M1 A428 Reservoir Daventry A45 See Inset Northampton A509 West A425 A6 M45 Haddon CreatonCreaton J16 Ravensthorpe A428 Brixworth J15a J17 Reservoir A5 J15 A43 A361 A428 Bedford A508 A361 Pitsford Towcester Ha M1 A509 rle Reservoir st on B5385 e R From M1 Northbound o Harborough a W d Road A43 Exit the M1 at junction 15a, Rothersthorpe Services and follow Long e l f signs to the A43. A5 Buckby o r Braunston d Once at the A43 roundabout, turn left and pass under the M1 to R Thorpeville o A508 arrive at a further roundabout, continue ahead. M1 a d Remain on the A43 over the next three roundabouts, at the next A45 roundabout take the third exit onto the A4500. Continue over the next two roundabouts and after a further 1/2 A5199 A5076 mile turn left onto the A428 Spencer Bridge Road. A428 Pass over the rail and river bridges and turn left onto the A5095 St Andrews Road. Inset At the junction with the A508 turn left onto Kingsthorpe Road. -

452 PLU TRADES. ( NORTH.Lmptoxsbire'

• 452 PLU TRADES. ( NORTH.lMPTOXSBIRE'. PLUMBERS & GLAZIERS-continued. tRoberts Daniel, 6 Hopes place,. Bar- Parsons Edwd. Raunds, Wellingboro" Butcher J.77Woolmonger st.Nrthmptn rack road, Northampton Pell W. New Barton, Earls Barton, Butcher Thomas James, u2 Welling Roberts William Cavens, 47 Campbell Northampton borough road, Northampton street, Nort.hampton Pitts George, 15 "h"'ellington place, Bar- Butterworth E. J. Corby, Kettering Roberts William Saunders, 102 St. rack road, Northampton tCaswell Frederick, Wellingborough James's road, Northampton Pitts Joseph, 45 Bridge st. Nrthmptn road, Rushden S.O Sanders Brothers, 3 Church way, Wel- Prue John H. 17 Sheep st. Nrthmptn Chattell Waiter Brown, 2 Junction rd. lingborough Samways W. D. 11 Earl st.Nrthmptn Kingsley park, Northampton Sanderson Henry Willy, Green's Nor- Saxby Bros. Midland rd. Wellingbora" Clarke \~i!liam, !slip, Thrapston ton, Towcester Saxby & Parker, Higham Ferrers S.O tCole Thomas, 157 Alexandra rd. & tSharp Thomas Edward, Thrapston Sharman W. C. 10 Earl st.Nrthmptn Mill road, W ellingborough. See Shelton G. L. Higham Ferrers S.O Shillaker William, 3I Broad Bridge advertisement Simons T. H. & Son,High st.Brackley street, Peterborough Constab;e Jn. S. Blakesley, Towcester Smart & Son, Yelvertoft, Rugby Stokes SI. 'I'I'I Cromwell rd.Peterboro• tCooper W. & Son,4 Gas st.Kettering tSmart Jn.Padmore,Higb st.Towcestr Turnill Thos. Raunds, Wellingboro' tCooper J n. N. Queen st. Kettering Smart William, Crick, Rugby Ward !Mrs. M. ·14 Horse mkt.Kettrng Couper Alfred, Badby road, Daventry Smith Bros. 21S Gold st. Northampton West John, Bridge street, Roth- Cracknell Jn. Huntly grove & Princes tSpicer Wr;n.Hy.