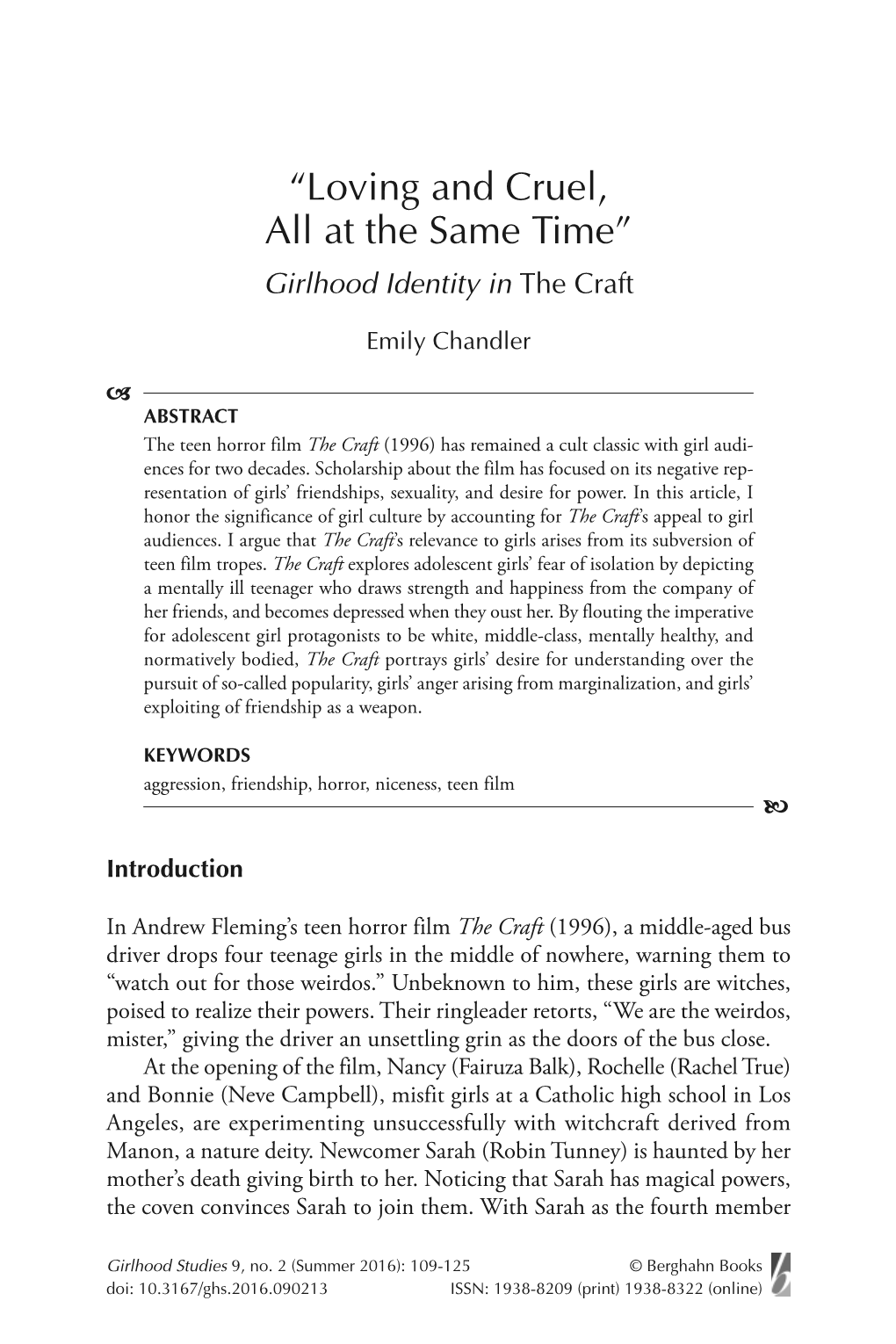

“Loving and Cruel, All at the Same Time” Girlhood Identity in the Craft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manuel Carballo

Divendres 18 d’octubre de 2013 · Número 8 9 Alejandro Jodorowsky 10 Manuel Carballo 11 Frank Pavich 12 Marcelo Panozzo www.sitgesfilmfestival.com Diari del festival 2 Divendres 18 d’octubre 2013 INFOrmaCIÓ I VENDA D’ENTraDES Compra les teves entrades anticipades * Excepcions dels abonaments Fan- a través de Telentrada de Catalunya- tàstics i dels carnets de descompte: Caixa, per internet a (www.telentrada. els descomptes no són aplicables com), per telèfon trucant al 902 10 12 a les gales d’Inauguració i de Clo- 12 o a les oficines de CatalunyaCaixa enda, maratons del 20 d’octubre, maratons de matinada, les sessions PREUS (IVA inclós) Despertador, Abonament Matinée, 9€: Secció Oficial Fantàstic a competi- Abonament Auditori, Butaca VIP i ció, Secció Oficial Fantàstic Especials, Localitat Numerada. Secció Oficial Fantàstic Galas, Secció Oficial Fantàstic Panorama en competi- VENDA D’ENTRADES ció, Secció Oficial Noves Visions Emer- Pots comprar les teves entrades gents, Secció Oficial Noves Visions Ex- anticipades a través de Telentrada perimenta, Secció Oficial Noves Visions de CatalunyaCaixa, per internet a Ficció, Secció Oficial Noves Visions No www.telentrada.com, per telèfon tru- Ficció, Secció Oficial Noves Visions Petit cant al 902 10 12 12 o a les oficines 1 Estacio Format, Panorama Especial, Sessions de CatalunyaCaixa. 2 Bus Sitges-Barcelona | Sitges-Vilanova Especial, Secció Seven Chances, Ses- 3 Cinema Prado sions Sitges Family, Focus Asia, Secció De l’11 al 20 d’octubre també les po- 4 Cinema El Retiro Anima’t i Sessions 3D dràs adquirir a les taquilles de l’Audi- 5 Cap de la Vila 6€: Secció Retrospectiva i Homenat- tori situades a la sala Tramuntana de 6 Jardins d’El Retiro. -

KATHRINE GORDON Hair Stylist IATSE 798 and 706

KATHRINE GORDON Hair Stylist IATSE 798 and 706 FILM DOLLFACE Department Head Hair/ Hulu Personal Hair Stylist To Kat Dennings THE HUSTLE Personal Hair Stylist and Hair Designer To Anne Hathaway Camp Sugar Director: Chris Addison SERENITY Personal Hair Stylist and Hair Designer To Anne Hathaway Global Road Entertainment Director: Steven Knight ALPHA Department Head Studio 8 Director: Albert Hughes Cast: Kodi Smit-McPhee, Jóhannes Haukur Jóhannesson, Jens Hultén THE CIRCLE Department Head 1978 Films Director: James Ponsoldt Cast: Emma Watson, Tom Hanks LOVE THE COOPERS Hair Designer To Marisa Tomei CBS Films Director: Jessie Nelson CONCUSSION Department Head LStar Capital Director: Peter Landesman Cast: Gugu Mbatha-Raw, David Morse, Alec Baldwin, Luke Wilson, Paul Reiser, Arliss Howard BLACKHAT Department Head Forward Pass Director: Michael Mann Cast: Viola Davis, Wei Tang, Leehom Wang, John Ortiz, Ritchie Coster FOXCATCHER Department Head Annapurna Pictures Director: Bennett Miller Cast: Steve Carell, Channing Tatum, Mark Ruffalo, Siena Miller, Vanessa Redgrave Winner: Variety Artisan Award for Outstanding Work in Hair and Make-Up THE MILTON AGENCY Kathrine Gordon 6715 Hollywood Blvd #206, Los Angeles, CA 90028 Hair Stylist Telephone: 323.466.4441 Facsimile: 323.460.4442 IATSE 706 and 798 [email protected] www.miltonagency.com Page 1 of 6 AMERICAN HUSTLE Personal Hair Stylist to Christian Bale, Amy Adams/ Columbia Pictures Corporation Hair/Wig Designer for Jennifer Lawrence/ Hair Designer for Jeremy Renner Director: David O. Russell -

Partition Prod.Notes Final

PARTITION PRODUCTION NOTES India, 1947, in the last days of the British Raj, a way of life is coming to an end. Intertwining cultures are forced to separate. As PARTITION divides a nation, two lives are brought together in a profound and sweeping story that reveals the tenderness of the human heart in the most violent of times. From award-winning Kashmiri born filmmaker Vic Sarin comes PARTITION— A timeless love story played out in the foothills of the Himalayas against a backdrop of political and religious upheaval. The Story Line Determined to leave the ravages of war behind, 38-year-old Gian Singh (Jimi Mistry), a Sikh, resigns from the British Indian Army to a quiet life as a farmer. His world is soon thrown in turmoil, when he suddenly finds himself responsible for the life of a 17-year-old Muslim girl, Naseem Khan (Kristin Kreuk) traumatized by the events that separated her from her family. Slowly, resisting all taboos, Gian finds himself falling in love with the vulnerable Naseem and she shyly responds. In a moving and epic story, woven into an exotic tapestry, they battle the forces that haunt their innocent love, fighting the odds to survive in a world surrounded by hate. The History Director Vic Sarin’s memories of India—the things he witnessed and the stories he heard as a child—have left an indelible impression on him. The tragic story of a friend of Sarin’s father - a Sikh gentleman who loved a Muslim woman - became the inspiration for the two archetypal Romeo and Juliet characters in his movie. -

Completeandleft Felix ,Adler ,Educator ,Ethical Culture Ferrán ,Adrià ,Chef ,El Bulli FA,F

MEN WOMEN 1. FA Frankie Avalon=Singer, actor=18,169=39 Fiona Apple=Singer-songwriter, musician=49,834=26 Fred Astaire=Dancer, actor=30,877=25 Faune A.+Chambers=American actress=7,433=137 Ferman Akgül=Musician=2,512=194 Farrah Abraham=American, Reality TV=15,972=77 Flex Alexander=Actor, dancer, Freema Agyeman=English actress=35,934=36 comedian=2,401=201 Filiz Ahmet=Turkish, Actress=68,355=18 Freddy Adu=Footballer=10,606=74 Filiz Akin=Turkish, Actress=2,064=265 Frank Agnello=American, TV Faria Alam=Football Association secretary=11,226=108 Personality=3,111=165 Flávia Alessandra=Brazilian, Actress=16,503=74 Faiz Ahmad=Afghan communist leader=3,510=150 Fauzia Ali=British, Homemaker=17,028=72 Fu'ad Aït+Aattou=French actor=8,799=87 Filiz Alpgezmen=Writer=2,276=251 Frank Aletter=Actor=1,210=289 Frances Anderson=American, Actress=1,818=279 Francis Alexander+Shields= =1,653=246 Fernanda Andrade=Brazilian, Actress=5,654=166 Fernando Alonso=Spanish Formula One Fernanda Andrande= =1,680=292 driver.=63,949=10 France Anglade=French, Actress=2,977=227 Federico Amador=Argentinean, Actor=14,526=48 Francesca Annis=Actress=28,385=45 Fabrizio Ambroso= =2,936=175 Fanny Ardant=French actress=87,411=13 Franco Amurri=Italian, Writer=2,144=209 Firoozeh Athari=Iranian=1,617=298 Fedor Andreev=Figure skater=3,368=159 ………… Facundo Arana=Argentinean, Actor=59,952=11 Frickin' A Francesco Arca=Italian, Model=2,917=177 Fred Armisen=Actor=11,503=68 Frank ,Abagnale ,Criminal ,Catch Me If You Can François Arnaud=French Canadian actor=9,058=86 Ferhat ,Abbas ,Head of State ,President of Algeria, 1962-63 Fábio Assunção=Brazilian actor=6,802=99 Floyd ,Abrams ,Attorney ,First Amendment lawyer COMPLETEandLEFT Felix ,Adler ,Educator ,Ethical Culture Ferrán ,Adrià ,Chef ,El Bulli FA,F. -

Cine-Excess 13 Delegate Abstracts

Cine-Excess 13 Delegate Abstracts Alice Haylett Bryan From Inside to The Hills Have Eyes: French Horror Directors at Home and Abroad In an interview for the website The Digital Fix, French director Pascal Laugier notes the lack of interest in financing horror films in France. He states that after the international success of his second film Martyrs (2008) he received only one proposition from a French producer, but between 40 and 50 propositions from America: “Making a genre film in France is a kind of emotional roller-coaster” explains Laugier, “sometimes you feel very happy to be underground and trying to do something new and sometimes you feel totally desperate because you feel like you are fighting against everyone else.” This is a situation that many French horror directors have echoed. For all the talk of the new wave of French horror cinema, it is still very hard to find funding for genre films in the country, with the majority of French directors cutting their teeth using independent production companies in France, before moving over to helm mainstream, bigger-budget horrors and thrillers in the USA. This paper will provide a critical overview of the renewal in French horror cinema since the turn of the millennium with regard to this situation, tracing the national and international productions and co-productions of the cycle’s directors as they navigate the divide between indie horror and the mainstream. Drawing on a number of case studies including the success of Alexandre Aja, the infamous Hellraiser remake that never came into fruition, and the recent example of Coralie Fargeat’s Revenge, it will explore the narrative, stylistic and aesthetic choices of these directors across their French and American productions. -

Date Production Name Venue / Production Designer / Stylist Design

Date ProductionVenue Name / Production Designer / Stylist Design Talent 2015 Opera Komachi atOpera Sekidrera America Camilla Huey Designer 3 dresses, 3 wigs 2014 Opera Concert Alice Tully Hall Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Rebecca Ringle 2014 Opera Concert Carnegie Hall Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Rebecca Ringle 2014 Opera Concert Carnegie Hall Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Sara Jakubiak 2013 Opera Concert Bard University Opera Camilla Huey Designer 1 Gown Rebecca Ringle 1996 Opera Carmen Metropolitan Opera Leather Costumes 1996 Opera Midsummer'sMetropolitan Night's Dream Opera Leslie Weston / Izquierdo Human Pillar Set Piece 1997 Opera Samson & MetropolitanDelilah Opera Leslie Weston / Izquierdo Dyeing Costumes 1997 Opera Cerentola Metropolitan Opera Leslie Weston / Izquierdo Mechanical Wings 1997 Opera Madame ButterflyHouston Grand Opera Anita Yavich / Izquierdo Kimonos Hand Painted 1997 Opera Lillith Tisch Center for the Arts OperaCatherine Heraty / Izquierdo Costumes 1996 Opera Bartered BrideMetropolitan Opera Sylvia Nolan / Izquierdo Dancing Couple + Muscle Shirt 1996 Opera Four SaintsMetropolitan In Three Acts Opera Francesco Clemente/ Izquierdo FC Asssitant 1996 Opera Atilla New York City Opera Hal George / Izquierdo Refurbishment 1995 Opera Four SaintsHouston In Three Grand Acts Opera Francesco Clemente / Izquierdo FC Assistant 1994 Opera Requiem VariationsOpera Omaha Izquierdo 1994 Opera Countess MaritzaSanta Fe Opera Allison Chitty / Izquierdo 1994 Opera Street SceneHouston Grand Opera Francesca Zambello/ Izquierdo -

BULLETIN April 24, 2007 SERVING TOOELE COUNTY SINCE 1894 VOL

FRONT PAGE A1 www.tooeletranscript.com TUESDAY Family fights fires through the generations See B1 TOOELETRANSCRIPT BULLETIN April 24, 2007 SERVING TOOELE COUNTY SINCE 1894 VOL. 113 NO. 96 50¢ Hospital to expand Addition to Mountain West Medical Center will cater to women’s health needs by Mark Watson women can meet to learn the lat- STAFF WRITER est in the world of medicine and A new $4.5 million addition to treatment. Mountain West Medical Center Of the total cost of the new will double the facility’s ability to addition, $1.4 million will be spent care for female patients, accord- on state-of-the-art medical equip- ing to hospital CEO Chuck Davis. ment. Hospital officials announced Davis said market demand was the expansion plans at the behind the decision to expand. Healthy Woman Wellness Fair “The hospital opened on May Thursday night at Tooele High 17, 2002, and during the first year School. The new building will be we had 225 deliveries,” Davis said. located near the main hospital on “During 2006, we had 480 deliv- the northwest side and will have eries. Something needed to be a separate entrance and waiting done.” room, according to Davis. The Davis said the women of the 14,000-square-foot facility should world drive the medical services be completed by the fall of 2008. industry. The hospital is working on archi- “About 70 to 80 percent of med- tectural designs and will seek con- ical decisions are made by women struction bids later in the year. in the community,” he said. -

Sinner to Saint

FINAL-1 Sat, Nov 4, 2017 7:23:54 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of November 11 - 17, 2017 OLD FASHIONED SERVICE Sinner to saint FREE REGISTRY SERVICE Kimberly Hébert Gregoy and Jason Ritter star in “Kevin (Probably) Saves the World” Massachusetts’ First Credit Union In spite of his selfish past — or perhaps be- Located at 370 Highland Avenue, Salem John Doyle cause of it — Kevin Finn (Jason Ritter, “Joan of St. Jean's Credit Union INSURANCEDoyle Insurance AGENCY Arcadia”) sets out to make the world a better 3 x 3 Voted #1 1 x 3 place in “Kevin (Probably) Saves the World,” Serving over 15,000 Members • A Part of your Community since 1910 Insurance Agency airing Tuesday, Nov. 14, on ABC. All the while, a Supporting over 60 Non-Profit Organizations & Programs celestial being known as Yvette (Kimberly Hé- bert Gregory, “Vice Principals”) guides him on Serving the Employees of over 40 Businesses Auto • Homeowners his mission. JoAnna Garcia Swisher (“Once 978.219.1000 • www.stjeanscu.com Business • Life Insurance Upon a Time”) and India de Beaufort (“Veep”) Offices also located in Lynn, Newburyport & Revere 978-777-6344 also star. Federally Insured by NCUA www.doyleinsurance.com FINAL-1 Sat, Nov 4, 2017 7:23:55 PM 2 • Salem News • November 11 - 17, 2017 TV with soul: New ABC drama follows a man on a mission By Kyla Brewer find and anoint a new generation the Hollywood ranks with roles in With You,” and has a recurring role ma, but they hope “Kevin (Proba- TV Media of righteous souls. -

Cast Biographies

CAST BIOGRAPHIES MICHAEL SHANNON (Gary Noesner) Academy Award®, Golden Globe® and Tony Award® nominated actor Michael Shannon continues to make his mark in entertainment, working with the industry's most respected talent and treading the boards in notable theaters around the world. Shannon will next be seen in Guillermo del Toro's The Shape of Water, a love story set against the backdrop of Cold War-era America. The film co-stars Sally Hawkins, Richard Jenkins, Michael Stuhlbarg and Octavia Spencer. Fox Searchlight will release the film December 2017. In 2018, Shannon will return to Red Orchard Theatre for its 25th Anniversary to direct the world premiere of Traitor, Brett Neveu's adaption of Henrik Ibsen's Enemy of the People. Traitor will include ensemble members Dado, Larry Grimm, Danny McCarthy, Guy Van Swearingen and Natalie West and will run from January 5, 2018 through February 25, 2018. Back on the big screen, Shannon will then be seen in the Nicolai Fuglsig’s 12 Strong opposite Chris Hemsworth. The project follows a team of CIA agents and special forces who head into Afghanistan in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks in an attempt to dismantle the Taliban. Warner Brothers is releaseing the film in January 2018. Later next year, Shannon will also be seen in writer-director Elizabeth Chomko’s drama, What They Had, opposite Hilary Swank. The story centers on a woman who must fly back to her hometown when her Alzheimer's-stricken mother wanders into a blizzard and the return home forces her to confront her past, which includes her brother (Shannon). -

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS BEST FIRST SCREENPLAY 2012 NOMINEES (Winners in bold) *Will Reiser 50/50 BEST FEATURE (Award given to the producer(s)) Mike Cahill & Brit Marling Another Earth *The Artist Thomas Langmann J.C. Chandor Margin Call 50/50 Evan Goldberg, Ben Karlin, Seth Rogen Patrick DeWitt Terri Beginners Miranda de Pencier, Lars Knudsen, Phil Johnston Cedar Rapids Leslie Urdang, Dean Vanech, Jay Van Hoy Drive Michel Litvak, John Palermo, BEST FEMALE LEAD Marc Platt, Gigi Pritzker, Adam Siegel *Michelle Williams My Week with Marilyn Take Shelter Tyler Davidson, Sophia Lin Lauren Ambrose Think of Me The Descendants Jim Burke, Alexander Payne, Jim Taylor Rachael Harris Natural Selection Adepero Oduye Pariah BEST FIRST FEATURE (Award given to the director and producer) Elizabeth Olsen Martha Marcy May Marlene *Margin Call Director: J.C. Chandor Producers: Robert Ogden Barnum, BEST MALE LEAD Michael Benaroya, Neal Dodson, Joe Jenckes, Corey Moosa, Zachary Quinto *Jean Dujardin The Artist Another Earth Director: Mike Cahill Demián Bichir A Better Life Producers: Mike Cahill, Hunter Gray, Brit Marling, Ryan Gosling Drive Nicholas Shumaker Woody Harrelson Rampart In The Family Director: Patrick Wang Michael Shannon Take Shelter Producers: Robert Tonino, Andrew van den Houten, Patrick Wang BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE Martha Marcy May Marlene Director: Sean Durkin Producers: Antonio Campos, Patrick Cunningham, *Shailene Woodley The Descendants Chris Maybach, Josh Mond Jessica Chastain Take Shelter -

The Seven Secret Arts of Glantri

TTHHEE SSEEVVEENN SSEECCRREETT AARRTTSS OOFF GGLLAANNTTRRII By Matteo Barnabè An adaption for D&D 3.5E CONTENTS THE SEVEN SECRET ARTS OF GLANTRI ..................................................................................... 1 Introduction to the Secret Arts ......................................................................................... 1 Learning the Art ............................................................................................................... 1 Leaving the sect ................................................................................................................ 2 Becoming Grand Master ................................................................................................... 2 MASTER OF ALCHEMY .............................................................................................................. 3 Requirements ................................................................................................................... 3 Class Skills ....................................................................................................................... 3 Class Features .................................................................................................................. 3 MASTER OF CRYPTOMANCY ..................................................................................................... 5 Requirements ................................................................................................................... 5 Class Skills ...................................................................................................................... -

YA Fantasy Book Guide

YA Fantasy Book Guide Novels (Cont.) Novels Sweetblood (Hautman) Damsel (Arnold) Daggers & Debutantes (Hawkins) The Deepest Roots (Asebedo) The Love That Split the World (Henry) Sleepless (Balog) The Lantern’s Ember (Houck) Starstruck (Balog) Tender Morsels (Lanagan) Wonder Woman: Warbringer (Bardugo) The Books of Earthsea (LeGuin) Heart of Thorns (Barton) Now You See Her (Leighton) Girls Made of Snow & Glass (Bashardoust) Ash (Lo) Chime (Billingsley) Bad Blood (Lunette) The Darkest Part of the Forest (Black) Catwoman: Soulstealer (Maas) Merrow (Braxton-Smith) When the Moon Was Ours (McLemore) In Other Lands (Brennen) Sang Spell (Naylor) Buffy: Tales of the Slayer (Buffy) And the Ocean Was Our Sky (Ness) Wish (Bullen) The Scourge (Nielsen) The Good Demon (Cajoleas) Newt’s Emerald (Nix) Out of the Blue (Cameron) Robots Vs. Fairies (Parisien) The Siren (Cass) East (Pattou) Tales from the Shadowhunter Academy (Clare) Andromeda Klein (Portman) The Bane Chronicles (Clare) A Hat Full of Sky (Pratchett) Ghosts of the Shadow Market (Clare) The Amazing Maurice & His Educated Atlantia (Condie) Rodents (Practchett) Fade (Cormier) The Wee Free men (Pratchett) Transcendent (Detweiler) Miles Morales: Spider-Man (Reynolds) Tears of the Salamander (Dickinson) Bone Gap (Ruby) Entwined (Dixon) The Little Prince (Saint-Exupery) Fire & Heist (Durst) The Rithmatist (Sanderson) A Kiss In Time (Flinn) More Happy Than Not (Silvera) Spellbook of the Lost & Found (Fowley-Doyle) Iron Cast (Soria) The Graveyard Book (Gaiman) All the Crooked Saints (Stiefvater) The Sleeper & the Spindle (Gaiman) A Room Away From the Wolves (Suma) M is for Magic (Gaiman) Tales From the Inner City (Tan) Stardust (Gaiman) Trollhunters (Toro) Strange Grace (Gratton) The Boneless Mercies (Tucholke) The Waning Age (Grove) Voices of Dragons (Vaughn) A Skinful of Shadows (Hardinge) Welcome to Bordertown (Welcome) Tess of the Road (Hartman) Poison (Wooding) Seraphina (Hartman) Blood & Sand (Wyk) (Cont.