Downloaded from Brill.Com09/28/2021 03:06:56PM This Is an Open Access Article Distributed Under the Terms of the Cc by 4.0 License

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nepal-India Think Tank Summit 2018 Opening Ceremony Session I

Summit Schedule Nepal-India Think Tank Summit 2018 Registration and Breakfast 8:00 AM- 9:00 AM 9:00 AM-10:00 AM Opening Ceremony Opening Remarks: Mr. Shyam KC, Research and Development Director, AIDIA Chair Remarks: Shri Shakti Sinha, Director, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML) Special Remarks: H.E. Manjeev Singh Puri, Ambassador of India to Nepal Keynote Speech: Shri Ram Madhav, National General Secretary, Bharatiya Janata Party and Director, India Foundation Special Guest Remarks: Hon'ble Mr. Matrika Prasad Yadav, Minister for Industry, Commerce & Supplies Special Address: Chief Guest Rt. Hon’ble Former Prime Minister of Nepal, Pushpa Kamal Dahal ‘Prachanda’ Vote of Thanks: Mr. Sunil KC, Founder/CEO, Asian Institute and Diplomacy and International Affairs (AIDIA) Opening Session Brief Think Tank, as a shaper of various policy related questions, acts as a bridge between the world of idea and action. And it recommends best possible policy options to the government to meet the daunting challenges in the domestic and the international affairs. The session aims to locate the major role of the think tank in addressing the emerging foreign policy questions and the importance of cooperation between the think-tank of Nepal and India. 10:00 AM-11:30 AM Session I: Building Innovative Cooperation between Indo-Nepal Think Tank: The Partnership Chair Hon'ble Mr. Gagan Thapa, Member of Parliament, Nepali Congress Panelists: Prof. Dr Shambhu Ram Simkhada, Convener, CNI Think Tank, Former Permanent Representative of Nepal to the United Nations Major General Rajiv Narayanan, AVSM, VSM (Retd) Shri Shakti Sinha, Director, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML) Dr. -

1. Appointments

Current Affairs July to December (Mid)-2016 Download from www.arunacademy.in - 1 - Today we, Arun Academy providing List of important Banking and Financial Sector, National, International and other appointments during July to December(Mid)-2016. Appointments related questions are frequently asked in most of the competitive exams. This will be very useful for upcoming Bank PO/Clerk Mains exam, Railways and TNPSC Group exams too. 1) APPOINTMENTS 1) FINANCE AND BANKING SECTOR ORIENTED i. Goverment Orgnisation ii. World Organistion iii. Private Organisation 2) CENTRAL GOVERNMENT 3) INTERNATIONAL: (Government) 4) OTHERS: (Private Organisations) 1. APPOINTMENTS 1) BANKING AND FINANCE: Goverment Orgnisation: Ajay Bhushan Pandey is appointed as Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI). Gautam Eknath Thakur has been elected Chairman of the leading co- operative Bank - Saraswat Bank. Urjit R Patel has been appointed as New Governor of Reserve Bank of India (RBI) for a period of 3 years with effect from 4th September, 2016. He is 24th Governor of RBI. Dinesh Kumar Khara has been appointed Managing Director (MD) of State Bank of India (SBI), India’s largest Bank. He was previously working as chief of SBI Funds Management Pvt. Ltd. Government appointed Ashok Kumar Garg, Raj Kamal Verma, Copal Murli Bhagat, and Himanshu Joshi as Executive Directors in Bank of Baroda, Union Bank of India, Corporation Bank, and Oriental Bank of Commerce respectively. Sudarshan Sen has been appointed as Executive Director of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). He will replace NS Vishwanathan who was elevated as Deputy Governor of RBI. Government appointed R. -

Nepal's Future: in Whose Hands?

NEPAL’S FUTURE: IN WHOSE HANDS? Asia Report N°173 – 13 August 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION: THE FRAYING PROCESS ........................................................... 1 II. THE COLLAPSE OF CONSENSUS............................................................................... 2 A. RIDING FOR A FALL......................................................................................................................3 B. OUTFLANKED AND OUTGUNNED..................................................................................................4 C. CONSTITUTIONAL COUP DE GRACE..............................................................................................5 D. ADIEU OR AU REVOIR?................................................................................................................6 III. THE QUESTION OF MAOIST INTENT ...................................................................... 7 A. MAOIST RULE: MORE RAGGED THAN RUTHLESS .........................................................................7 B. THE VIDEO NASTY.......................................................................................................................9 C. THE BEGINNING OF THE END OR THE END OF THE BEGINNING?..................................................11 IV. THE ARMY’S GROWING POLITICAL ROLE ........................................................ 13 A. WAR BY OTHER MEANS.............................................................................................................13 -

Chennai Ias Academy-9043 211311/411 Tnpsc Current Affairs – September 2018

CHENNAI IAS ACADEMY-9043 211311/411 TNPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – SEPTEMBER 2018 CHENNAI IAS ACADEMY Vellore & Tiruvannamalai ENGLISH MEDIUM www.chennaiiasacademy.com chennaiiasacademy Contact : 9043 211 311 / 411 1 CHENNAI IAS ACADEMY-9043 211311/411 Current Affairs For TNPSC Examinations SEPTEMBER 2018 SI.NO CONTENTS PAGE.NO 1. TAMILNADU 03 - 06 2. NATIONAL 06 – 38 3. INTERNATIONAL 38 – 48 4. APPOINTMENTS & 48 – 53 RESIGNS 5. SPORTS 53 – 62 6. SCIENCE AND 62 – 64 TECHNOLOGY 7. IMPORTANT DAYS 64 – 68 8. AWARDS 68 - 72 2 CHENNAI IAS ACADEMY-9043 211311/411 TAMILNADU Coastal Zone Management plan Tamil Nadu government submitted the final draft of „Coastal zone management plan‟ to the Union ministry of Environment, Forests and climate change. As per the Tamil Nadu prison manual, (Open Air Prison) the concept of open- air prison is to relieve congestion in walled prisons, train inmates in proper methods of agriculture for future rehabilitation and make prisons self- sufficient in agri production. It also aims to give prisoners with good conduct a certain amount of freedom. The plan divides 1,076 km long coastline into 6 categories (6 CRZs - Coastal People convicted under provisions of Regulation Zone) to preserve its marine Central Act XLV of 1860, habitual offenders, ecology, covering 13 TN coastal districts and women prisoners, political prisoners, hired and 28 islands. professional murderers, ‗A‘ class prisoners and inmates having tendency to escape are not They are named as CRZ IA, CRZ eligible for the provision. IB,CRZ II, CRZ III, CRZ IVA and CRZ IVB. The prisons department had already The state has 1 Marine National Park established such a facility in Coimbatore, that is Gulf of Manna. -

19 April 2021 Excellency, We Have the Honour to Address You in Our

PALAIS DES NATIONS • 1211 GENEVA 10, SWITZERLAND Mandates of the Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association; the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances; the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders; the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers and the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment REFERENCE: AL NPL 2/2021 19 April 2021 Excellency, We have the honour to address you in our capacities as Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association; Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances; Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders; Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers and Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, pursuant to Human Rights Council resolutions 41/12, 45/3, 43/16, 44/8 and 43/20. In this connection, we would like to bring to the attention of your Excellency’s Government information we have received concerning the appointment of new members of the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC), that is not in compliance with the Paris Principles and severely undermines the NHRC’s independence. According to the information received: On 20 April 2020, the President issued Ordinance 1 (of Nepali year 2077) aimed at restructuring the Constitutional Council. The Ordinance attracted a good deal of political and public opposition and was rolled back on 24 April 2020. On 15 December 2020, the President of Nepal issued Ordinance 10 (of Nepali year 2077) to amend the Constitutional Council (Functions, Duties, Powers and Procedures) Act, 2010, allowing the Council to hold its meetings without fulfillment of the quorum and to take decisions based on simple majority. -

General Studies Series

IAS General Studies Series Current Affairs (Prelims), 2013 by Abhimanu’s IAS Study Group Chandigarh © 2013 Abhimanu Visions (E) Pvt Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system or otherwise, without prior written permission of the owner/ publishers or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act, 1957. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claim for the damages. 2013 EDITION Disclaimer: Information contained in this work has been obtained by Abhimanu Visions from sources believed to be reliable. However neither Abhimanu's nor their author guarantees the accuracy and completeness of any information published herein. Though every effort has been made to avoid any error or omissions in this booklet, in spite of this error may creep in. Any mistake, error or discrepancy noted may be brought in the notice of the publisher, which shall be taken care in the next edition but neither Abhimanu's nor its authors are responsible for it. The owner/publisher reserves the rights to withdraw or amend this publication at any point of time without any notice. TABLE OF CONTENTS PERSONS IN NEWS .............................................................................................................................. 13 NATIONAL AFFAIRS .......................................................................................................................... -

South Asia Judicial Barometer

SOUTH ASIA JUDICIAL BAROMETER 1 The Law & Society Trust (LST) is a not-for- The Asian Forum for Human Rights and profit organisation engaged in human rights Development (FORUM-ASIA) works to documentation, legal research and advocacy promote and protect human rights, in Sri Lanka. Our aim is to use rights-based including the right to development, strategies in research, documentation and through collaboration and cooperation advocacy in order to promote and protect among human rights organisations and human rights, enhance public accountability defenders in Asia and beyond. and respect for the rule of law. Address : Address : 3, Kynsey Terrace, Colombo 8, S.P.D Building 3rd Floor, Sri Lanka 79/2 Krungthonburi Road, Tel : +94 11 2684845 Khlong Ton Sai, +94 11 2691228 Khlong San Bangkok, Fax : +94 11 2686843 10600 Thailand Web : lawandsocietytrust.org Tel : +66 (0)2 1082643-45 Email : [email protected] Fax : +66 (0)2 1082646 Facebook : www.fb.me/lstlanka Web : www.forum-asia.org Twitter : @lstlanka E-mail : [email protected] Any responses to this publication are welcome and may be communicated to either organisation via email or post. The opinions expressed in this publication are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publishers. Acknowledgements: Law & Society Trust and FORUM-ASIA would like to thank Amila Jayamaha for editing the chapters, Smriti Daniel for proofreading the publication and Dilhara Pathirana for coordinating the editorial process. The cover was designed by Chanuka Wijayasinghe, who is a designer based in Colombo, Sri Lanka. DISCLAIMER: The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of LST and FORUM-ASIA and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. -

Nepali Times

#415 29 August - 4 September 2008 16 pages Rs 30 Weekly Internet Poll # 415 Q. What should the prime minister have worn during his swearing in? Total votes: 5,742 Love thy neighbour MALLIKA ARYAL powerplay in South Asia.’ control mode before Yadav in NEW DELHI The opposition BJP, which arrived, dismissing the has no love for Nepal’s Maoists, controversy as “pointless”. He Weekly Internet Poll # 416. To vote go to: www.nepalitimes.com said that now that they are in added: “Ties with India are in a Q. The Prime Minister should have: t’s an indication of just how Gone to Delhi before Beijing sensitive India-Nepal government the former rebels different category.” z Did right by going to China first relations have become that should behave more responsibly. Does it matter? I few in the New Delhi foreign “The Maoists need to change policy establishment want to their overall attitude towards speak even off the record to a India because they Nepali journalist these days. haven’t been especially By ignoring Indian concerns warm towards us,” BJP and accepting Beijing’s invitation leader N N Jha told to the Olympics closing Nepali Times. ceremony last week, Prime Prime Minsiter Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal set Dahal’s Beijing alarm bells ringing here. Indian controversy was replaced politicians and foreign policy by the Kosi embankment bureaucrats tried to play down collapse this week as Indian Dahal’s ‘China card’, but the officials realised the full extent military-intelligence of the flood crisis in eastern establishment, Bihar. The Kosi changing its the course has made 60,000 opposition homeless in Nepal, but BJP and downstream in India the some number affected has reached a hawkish staggering four million. -

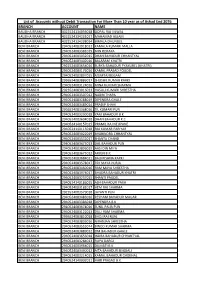

Branch Account Name

List of Accounts without Debit Transaction For More Than 10 year as of Ashad End 2076 BRANCH ACCOUNT NAME BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134056018 GOPAL RAJ SILWAL BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134231017 MAHAMAD ASLAM BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134298014 BIMALA DHUNGEL BENI BRANCH 2940524083918012 KAMALA KUMARI MALLA BENI BRANCH 2940524083381019 MIN ROKAYA BENI BRANCH 2940524083932015 DHAN BAHADUR CHHANTYAL BENI BRANCH 2940524083402016 BALARAM KHATRI BENI BRANCH 2922524083654016 SURYA BAHADUR PYAKUREL (KHATRI) BENI BRANCH 2940524083176016 KAMAL PRASAD POUDEL BENI BRANCH 2940524083897015 MUMTAJ BEGAM BENI BRANCH 2936524083886017 SHUSHIL KUMAR KARKI BENI BRANCH 2940524083124016 MINA KUMARI SHARMA BENI BRANCH 2923524083016013 HASULI KUMARI SHRESTHA BENI BRANCH 2940524083507012 NABIN THAPA BENI BRANCH 2940524083288019 DIPENDRA GHALE BENI BRANCH 2940524083489014 PRADIP SHAHI BENI BRANCH 2936524083368016 TIL KUMARI PUN BENI BRANCH 2940524083230018 YAM BAHADUR B.K. BENI BRANCH 2940524083604018 DHAN BAHADUR K.C BENI BRANCH 2940524140157015 PRAMIL RAJ NEUPANE BENI BRANCH 2940524140115018 RAJ KUMAR PARIYAR BENI BRANCH 2940524083022019 BHABINDRA CHHANTYAL BENI BRANCH 2940524083532017 SHANTA CHAND BENI BRANCH 2940524083475013 DAL BAHADUR PUN BENI BRANCH 2940524083896019 AASI DIN MIYA BENI BRANCH 2940524083675012 ARJUN B.K. BENI BRANCH 2940524083684011 BALKRISHNA KARKI BENI BRANCH 2940524083578017 TEK MAYA PURJA BENI BRANCH 2940524083460016 RAM MAYA SHRESTHA BENI BRANCH 2940524083974017 BHADRA BAHADUR KHATRI BENI BRANCH 2940524083237015 SHANTI PAUDEL BENI BRANCH 2940524140186015 -

GARP-Nepal National Working Group (NWG)

GARP-Nepal National Working Group (NWG) Dr. Buddha Basnyat, Chair GARP- Nepal, Researcher/Clinician, Oxford University Clinical Research Unit-Nepal\ Patan Academy of Health Sciences Dr. Paras K Pokharel, Vice Chair- GARP Nepal, Professor of Public Health and Community Medicine, BP Koirala Institute of Health Sciences, Dharan Dr. Sameer Mani Dixit, PI GARP- Nepal, Director of Research, Center for Molecular Dynamics, Nepal Dr. Abhilasha Karkey, Medical Microbiologist, Oxford University Clinical Research Unit-Nepal\ Patan Academy of Health Sciences Dr. Bhabana Shrestha, Director, German Nepal Tuberculosis Project Dr. Basudha Khanal, Professor of Microbiology, BP Koirala Institute of Health Sciences, Dharan Dr. Devi Prasai, Member, Nepal Health Economist Association Dr. Mukti Shrestha, Veterinarian, Veterinary Clinics, Pulchowk Dr. Palpasa Kansakar, Microbiologist, World Health Organization Dr. Sharada Thapaliya, Associate Professor, Department of Pharmacology and Surgery, Agriculture and Forestry University–Rampur Mr. Shrawan Kumar Mishra, President, Nepal Health Professional Council Dr. Shrijana Shrestha, Dean, Patan Academy of Health Sciences GARP-Nepal Staff Santoshi Giri, GARP-N Country Coordinator, Global Antibiotic Resistance Partnership- Nepal/Nepal Public Health Foundation Namuna Shrestha, Programme Officer, Nepal Public Health Foundation International Advisors Hellen Gelband, Associate Director, Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy Ramanan Laxminarayan, GARP Principal Investigator, Director, Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy Nepal Situation Analysis and Recommendations Preface Nepal Situation Analysis and Recommendations Nepal Situation Analysis and Recommendations Acknowledgement This report on "Situation Analysis and Recommendations: Antibiotic Use and Resistance in Nepal" is developed by Global Antibiotic Resistance Partnership (GARP Nepal) under Nepal Public Health Foundation (NPHF). First of all, we are thankful to Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics and Policy (CDDEP) for their financial and technical support. -

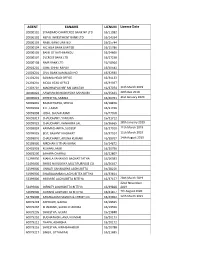

List of Active Agents

AGENT EANAME LICNUM License Date 20000101 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK NP LTD 16/11082 20000102 NEPAL INVESTMENT BANK LTD 16/14334 20000103 NABIL BANK LIMITED 16/15744 20000104 NIC ASIA BANK LIMITED 16/15786 20000105 BANK OF KATHMANDU 16/24666 20000107 EVEREST BANK LTD. 16/27238 20000108 NMB BANK LTD 16/18964 20901201 GIME CHHETRAPATI 16/30543 21001201 CIVIL BANK KAMALADI HO 16/32930 21101201 SANIMA HEAD OFFICE 16/34133 21201201 MEGA HEAD OFFICE 16/34037 21301201 MACHHAPUCHRE BALUWATAR 16/37074 11th March 2019 40000022 AAWHAN BAHUDAYSIYA SAHAKARI 16/35623 20th Dec 2019 40000023 SHRESTHA, SABINA 16/40761 31st January 2020 50099001 BAJRACHARYA, SHOVA 16/18876 50099003 K.C., LAXMI 16/21496 50099008 JOSHI, SHUVALAXMI 16/27058 50099017 CHAUDHARY, YAMUNA 16/31712 50099023 CHAUDHARY, KANHAIYA LAL 16/36665 28th January 2019 50099024 KARMACHARYA, SUDEEP 16/37010 11th March 2019 50099025 BIST, BASANTI KADAYAT 16/37014 11th March 2019 50099026 CHAUDHARY, ARUNA KUMARI 16/38767 14th August 2019 50199000 NIRDHAN UTTHAN BANK 16/14872 50401003 KISHAN LAMKI 16/20796 50601200 SAHARA CHARALI 16/22807 51299000 MAHILA SAHAYOGI BACHAT TATHA 16/26083 51499000 SHREE NAVODAYA MULTIPURPOSE CO 16/26497 51599000 UNNATI SAHAKARYA LAGHUBITTA 16/28216 51999000 SWABALAMBAN LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/33814 52399000 MIRMIRE LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/37157 28th March 2019 22nd November 52499000 INFINITY LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/39828 2019 52699000 GURANS LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/41877 7th August 2020 52799000 KANAKLAXMI SAVING & CREDIT CO. 16/43902 12th March 2021 60079203 ADHIKARI, GAJRAJ -

Nepali Times We Need Is an Atmosphere of Trust Between the REBELS WITHOUT a CAUSE Government and These Groups

#426 21 - 27 November 2008 16 pages Rs 30 Weekly Internet Poll # 426 Q. How would you assess the government’s first 100 days? Total votes: 4,440 Weekly Internet Poll # 427. To vote go to: www.nepalitimes.com Q. How do you characterise the rift in the Maoist party? Rising from the ashes he crises are coming thick has been tested to the limits and GOONDADOM: Nearly 2,000 subscriber copies of Himal Khabarpatrikaís and fast for the Maoists in he has proposed a middle path: a latest issue, featuring this exposÈ of the excesses by militant youth wings T government. The peace ‘transitional republic’. Until of various political parties, were destroyed when masked attackers set process is stuck over modalities press time on Thursday it looked fire to them at a distribution point in Maitighar on Sunday night. of army integration, internal like the ‘people’s republic’ ideological rifts have deadlocked wallahs had the numbers. A vote on Wednesday evening. EDITORIAL p2 its party conference and an by the cadre could still be However, the Maoists have Rebels without a cause alliance of other parties is on the over-ruled in the central been put on the defensive because attack over the YCL excesses. committee, but it would put of the discovery this week of the STATE OF THE STATE CK Lal The national conference of moral pressure on the moderates. bodies of two young men, believed Who’s in charge? p3 Maoist cadre to have been held on During a consultation with to have been executed by the YCL Thursday was postponed by a Maoist provincial councils, 12 of in Dhading last month.