The Early Diagnosis of Paresis.’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 05- Mental, Behavioral and Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Chapter 5 Mental, Behavioral and Neurodevelopmental disorders (F01-F99) Includes: disorders of psychological development Excludes2: symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified (R00-R99) This chapter contains the following blocks: F01-F09 Mental disorders due to known physiological conditions F10-F19 Mental and behavioral disorders due to psychoactive substance use F20-F29 Schizophrenia, schizotypal, delusional, and other non-mood psychotic disorders F30-F39 Mood [affective] disorders F40-F48 Anxiety, dissociative, stress-related, somatoform and other nonpsychotic mental disorders F50-F59 Behavioral syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors F60-F69 Disorders of adult personality and behavior F70-F79 Intellectual disabilities F80-F89 Pervasive and specific developmental disorders F90-F98 Behavioral and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence F99 Unspecified mental disorder Mental disorders due to known physiological conditions (F01-F09) Note: This block comprises a range of mental disorders grouped together on the basis of their having in common a demonstrable etiology in cerebral disease, brain injury, or other insult leading to cerebral dysfunction. The dysfunction may be primary, as in diseases, injuries, and insults that affect the brain directly and selectively; or secondary, as in systemic diseases and disorders that attack the brain only as one of the multiple organs or systems of the body that are involved. F01 Vascular dementia -

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders : Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines

ICD-10 ThelCD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines | World Health Organization I Geneva I 1992 Reprinted 1993, 1994, 1995, 1998, 2000, 2002, 2004 WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders : clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. 1.Mental disorders — classification 2.Mental disorders — diagnosis ISBN 92 4 154422 8 (NLM Classification: WM 15) © World Health Organization 1992 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from Marketing and Dissemination, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel: +41 22 791 2476; fax: +41 22 791 4857; email: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications — whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution — should be addressed to Publications, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; email: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers' products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. -

The Worried Well: Their Identification and Management

The worried well: their identification and management DAVID MILLER, DCPsych(NZ), Principal Clinical Psychologist and Honorary Lecturer in Psychiatry and Genito-Urinary Medicine TIMOTHY M. G. ACTON, DCPsych, Clinical Psychologist BARBARA HEDGE, DCPsych, Clinical Psychologist University College and Middlesex School of Medicine, London here in this unfortunate extreme, if but a pimple that they have symptoms of infection associated with appears or any slight ache is felt, they distract themselves human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the causative with terrible apprehensions And so strongly are they agent of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), for the most part possessed with this notion that any despite remaining infection free as verified by (often honest finds it more difficult to cure practitioner generally repeated) serological testing and clinical assessment [13- the imaginary evil than the real one. 15]. As a patient group, the worried well are distinguish- Freind, 1727 [1] able from those in the general population who experience raised anxiety as a result of media coverage of HIV/ Recent surveys of psychiatric and psychological disturb- AIDS, and who may as a consequence wish to be tested ance among patients attending sexually transmitted dis- for anti-HIV, but who experience long-term reassurance ease (STD) or genito-urinary medicine (GUM) clinics and absence of inappropriate worry as a result of negative have shown rates of 20-45 per cent morbidity [2-6]. clinical and laboratory findings. This latter group may be Examples -

Psychopathology-Madjirova.Pdf

NADEJDA PETROVA MADJIROVA PSYCHOPATHOLOGY psychophysiological and clinical aspects PLOVDIV 2005 I devote this book to all my patients that shared with me their intimate problems. © Nadejda Petrova Madjirova, 2015 PSYCHOPATHOLOGY: PSYCHOPHYSIOLOGICAL AND CLINICAL ASPECTS Prof. Dr. Nadejda Petrova Madjirova, MD, PhD, DMSs Reviewer: Prof. Rumen Ivandv Stamatov, PhD, DPS Prof. Drozdstoj Stoyanov Stoyanov, PhD, MD Design: Nadejda P. Madjirova, MD, PhD, DMSc. Prepress: Galya Gerasimova Printed by ISBN I. COMMON ASPECTS IN PSYCHOPHYSIOLOGY “A wise man ought to realize that health is his most valuable possession” Hippocrates C O N T E N T S I. Common aspects in psychophysiology. ..................................................1 1. Some aspects on brain structure. ....................................................5 2. Lateralisation of the brain hemispheres. ..........................................7 II. Experimental Psychology. ..................................................................... 11 1. Ivan Petrovich Pavlov. .................................................................... 11 2. John Watson’s experiments with little Albert. .................................15 III. Psychic spheres. ...................................................................................20 1. Perception – disturbances..............................................................21 2. Disturbances of Will .......................................................................40 3. Emotions ........................................................................................49 -

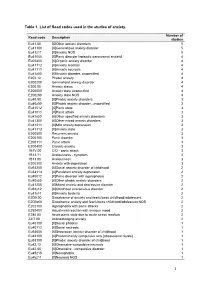

1 Table 1. List of Read Codes Used in the Studies of Anxiety

Table 1. List of Read codes used in the studies of anxiety. Number of Read code Description studies Eu41.00 [X]Other anxiety disorders 5 Eu41100 [X]Generalized anxiety disorder 5 Eu41z11 [X]Anxiety NOS 5 Eu41000 [X]Panic disorder [episodic paroxysmal anxiety] 4 Eu05400 [X]Organic anxiety disorder 4 Eu41112 [X]Anxiety reaction 4 Eu41111 [X]Anxiety neurosis 4 Eu41z00 [X]Anxiety disorder, unspecified 4 E202.12 Phobic anxiety 4 E200200 Generalised anxiety disorder 4 E200.00 Anxiety states 4 E200000 Anxiety state unspecified 4 E200z00 Anxiety state NOS 4 Eu40.00 [X]Phobic anxiety disorders 3 Eu40z00 [X]Phobic anxiety disorder, unspecified 3 Eu41012 [X]Panic state 3 Eu41011 [X]Panic attack 3 Eu41y00 [X]Other specified anxiety disorders 3 Eu41300 [X]Other mixed anxiety disorders 3 Eu41211 [X]Mild anxiety depression 3 Eu41113 [X]Anxiety state 3 E200500 Recurrent anxiety 3 E200100 Panic disorder 3 E200111 Panic attack 3 E200400 Chronic anxiety 3 1B1V.00 C/O - panic attack 3 1B13.11 Anxiousness - symptom 3 1B13.00 Anxiousness 3 E200300 Anxiety with depression 3 Eu93200 [X]Social anxiety disorder of childhood 2 Eu34114 [X]Persistant anxiety depression 2 Eu40012 [X]Panic disorder with agoraphobia 2 Eu40y00 [X]Other phobic anxiety disorders 2 Eu41200 [X]Mixed anxiety and depressive disorder 2 Eu93y12 [X]Childhood overanxious disorder 2 Eu41y11 [X]Anxiety hysteria 2 E2D0.00 Disturbance of anxiety and fearfulness childhood/adolescent 2 E2D0z00 Disturbance anxiety and fearfulness childhood/adolescent NOS 2 E202100 Agoraphobia with panic attacks 2 E292400 -

The Hypochondriac Syndromes: from Somatoform Disorders to Hypochondriac Paraphrenia

The hypochondriac syndromes: from somatoform disorders to hypochondriac paraphrenia Prof. Dr. Gerald Stöber Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy University of Würzburg, Germany [email protected] descriptive psychopathology symptom connections („Symptomverbindungen“) core syndrome / cardinal symptoms facultative symptoms clinical entities („Krankheitsgruppierungen“) nosology of psychic diseases differentiated aetiology Basic diagnostic differences between ICD-10/DSM-IV and Leonhard‘s nosology DSM-IV / ICD-10 Leonhard‘s nosology Diagnosis is made by the Diagnosis is made by the evidence of appearance of a specific symptom constellations minimum number of symptoms (specific symptoms form from a given symptom-catalogue characteristic syndromes), which have to exist over a which run a typical course given period of time. (prognosis). Hypochondriac Symptoms - ungrounded concerns to suffer from severe somatic illness: nosophobia, „malade imaginaire“ (provoked by discomforts) => „classical“ hypochondriac (neurosis) - bodily symptoms without adequate medical explanation - somatic sensation / physical misperception - alienation phenomena of the sphere of body feelings („Leibgefühlsstörung“) - somatic / hypochondriac hallucination Differentiation and significance of somatic sensations and body feelings I - homonym: usual, ordinary somatic sensations generalized or related to distinct organ systems pain and specific, well characterized discomforts; neurologic hyper-, hypo, dys- and paraesthesia „painful, burning, stinging, drilling, -

Tacliyeardia, Occasionlal Extr'a-S'ystoles with Palpitation, Ancl Disorders.3 an Intermnittenlt Pulse

X4°4144 MEDICALThuf BamwuJO SN&I1 THE VICIOUS CIRCLES OF NEURASTHENIA. [JUNE 27, '914 than a skeleton, and a fatal exitits ofteu closes the scene. THE VICIOUS CIRCLES OF NEUIRASTHENIA. Schofield thus describes tlle circle: BY A vicious circle is often kept up in these cases, wbich it is Absolutely essential to break. They begin, it may be, with loss Br Med J: first published as 10.1136/bmj.1.2791.1404 on 27 June 1914. Downloaded from JAMIESON B. HURRY, M.A., M.D., of appetite from some slight cause. -This'. .. leads to dis- READING. ordered thoughts, and the idea of disease is started. This, again, makes the appetite still more capricious; the thoughts NEURASTHENIA is mnore often than any otiler disorder therefore get still worse, and so the body starves the brain complicated by vicious circles. The result is a clhronic and the brain starves the body.6 self-perpetuating condition, distressing to the sufferer, In8omnnia.-Insomnia is anotlher psychogenous symptom harassinig to tile relatives, and baffling to the plhysician. of neurastlhenia wlhichl ofteln greatly impedes recovery; If a disorder is to be followed by speedy recovery, its the associated cerebral liyperaemia prevents the neurons reactions-for examiple, couglh, diarrhoea, pyrexia, etc.- obtaining the rest on wlliclh their recuperation so greatly must relieve thle primary condition. Such disorders may depends. -Sawyer tlhus describes the circle: be described as self-teriiiinating. Any cause whiclh directly prevents a repose duly deep of a - In nieurastilenia, on tlhe otiler lhalnd, tile reactions per- sufficient ntumber of those brain cells which are the organ-s of petuate tile primary conditioll. -

Risk of Depression and Anxiety in Adults with Cerebral Palsy

Supplementary Online Content Smith KJ, Peterson MD, O’Connell NE, et al. Risk of depression and anxiety in adults with cerebral palsy. JAMA Neurol. Published online December 28, 2018. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4147 eTable 1. Read codes and associated Read terms used to define Cerebral Palsy eTable 2. Risk of depression and anxiety in people with CP with and without co-morbid ID (excluding all people without CP who had a diagnosis of ID, n=24) eFigure. Kaplan Meier survival plots This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. © 2018 Smith KJ et al. JAMA Neurology. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/25/2021 eTable 1. Read codes and associated Read terms used to define Cerebral Palsy Read code Read term F23y400 Ataxic diplegic cerebral palsy F23y000 Ataxic diplegic cerebral palsy F137.11 Athetoid cerebral palsy F137000 Athetoid cerebral palsy F2B..00 Cerebral palsy F2Bz.00 Cerebral palsy NOS F230100 Cerebral palsy with spastic diplegia F23..00 Congenital cerebral palsy F23y300 Dyskinetic cerebral palsy F23..12 Infantile cerebral palsy F23y200 Spastic cerebral palsy F230111 Spastic diplegic cerebral palsy F2B1.00 Spastic hemiplegic cerebral palsy F2B0.00 Spastic quadriplegic cerebral palsy F23yz00 Other infantile cerebral palsy NOS Fyu9000 [X]Other infantile cerebral palsy F23y.00 Other congenital cerebral palsy F23y100 Flaccid infantile cerebral palsy F2By.00 Other cerebral palsy Fyu9.00 [X]Cerebral palsy and other paralytic syndromes F23z.00 Congenital cerebral palsy NOS F23..11 Congenital spastic cerebral palsy F23y600 Choreoathetoid cerebral palsy © 2018 Smith KJ et al. -

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines World Health Organization -1- Preface In the early 1960s, the Mental Health Programme of the World Health Organization (WHO) became actively engaged in a programme aiming to improve the diagnosis and classification of mental disorders. At that time, WHO convened a series of meetings to review knowledge, actively involving representatives of different disciplines, various schools of thought in psychiatry, and all parts of the world in the programme. It stimulated and conducted research on criteria for classification and for reliability of diagnosis, and produced and promulgated procedures for joint rating of videotaped interviews and other useful research methods. Numerous proposals to improve the classification of mental disorders resulted from the extensive consultation process, and these were used in drafting the Eighth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-8). A glossary defining each category of mental disorder in ICD-8 was also developed. The programme activities also resulted in the establishment of a network of individuals and centres who continued to work on issues related to the improvement of psychiatric classification (1, 2). The 1970s saw further growth of interest in improving psychiatric classification worldwide. Expansion of international contacts, the undertaking of several international collaborative studies, and the availability of new treatments all contributed to this trend. Several national psychiatric bodies encouraged the development of specific criteria for classification in order to improve diagnostic reliability. In particular, the American Psychiatric Association developed and promulgated its Third Revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, which incorporated operational criteria into its classification system. -

Hypochondriasis: Considerations for ICD-11 Odile A

Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria. 2014;36:S21–S27 ß 2014 Associac¸a˜ o Brasileira de Psiquiatria doi:10.1590/1516-4446-2013-1218 UPDATE ARTICLE Hypochondriasis: considerations for ICD-11 Odile A. van den Heuvel,1,2 David Veale,3,4 Dan J. Stein5 1Department of Psychiatry, VU University Medical Center (VUmc), Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 2Department of Anatomy & Neurosciences, VUmc, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 3Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London, London, UK. 4Center for Anxiety Disorders and Trauma, South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK. 5Department of Psychiatry, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa. The World Health Organization (WHO) is currently revisiting the ICD. In the 10th version of the ICD, approved in 1990, hypochondriacal symptoms are described in the context of both the primary condition hypochondriacal disorder and as secondary symptoms within a range of other mental disorders. Expansion of the research base since 1990 makes a critical evaluation and revision of both the definition and classification of hypochondriacal disorder timely. This article addresses the considerations reviewed by members of the WHO ICD-11 Working Group on the Classification of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders in their proposal for the description and classification of hypochondriasis. The proposed revision emphasizes the phenomenological overlap with both anxiety disorders (e.g., fear, hypervigilance to bodily symptoms, and avoidance) and obsessive-compulsive and related disorders (e.g., preoccupation and repetitive behaviors) and the distinction from the somatoform disorders (presence of somatic symptom is not a critical characteristic). This revision aims to improve clinical utility by enabling better recognition and treatment of patients with hypochondriasis within the broad range of global health care settings. -

A Grounded Theory of Personal Recovery Among People with Mental Illness in Qatar

A GROUNDED THEORY OF PERSONAL RECOVERY AMONG PEOPLE WITH MENTAL ILLNESS IN QATAR A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health 2018 Jason Hickey School of Health Sciences 1 Contents List of tables ......................................................................................................................... 5 List of figures ........................................................................................................................ 5 List of appendices ................................................................................................................ 5 Declaration ........................................................................................................................... 7 Copyright statement ............................................................................................................ 8 Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................ 9 Personal statement ............................................................................................................ 10 Use of the alternative format ............................................................................................ 11 Chapter 1. Introduction and background .............................................................................. 13 1.1 Introduction .......................................................................................................... -

Study Protocol Use of Benzodiazepines and Risk of Hip/Femur Fracture

WP2 Framework for pharmacoepidemiological studies WG1 Databases Study Protocol Use of benzodiazepines and risk of hip/femur fracture. A methodological comparison across data sources and epidemiological design. Version: Final Nov 14, 2011 with Amendment 1 approved 29 Feb 2012 PROTECT_WP2_Final Protocol_Benzo_HIP fracture_Nov14 2011Amend1_approved29Feb2012 Page 1 of 177 WG1 Drug AE group Name Role Francisco de Abajo 1, 2 Protocol Lead Luis Alberto García Rodríguez 3 Protocol Backup Ulrik Hesse 4 Protocol Reviewer Andrew Bate 5 Protocol Reviewer Saga Johanson 6 Protocol Reviewer Frank de Vries 7 Protocol Reviewer Marietta Rottenkolber 8 Database 1 (Bavaria) lead Joerg Hasford 8 Database 1 (Bavaria) backup Miguel Gil 2 Database 2 (Bifap) lead Consuelo Huerta 2 Database 2 (Bifap) backup Ulrik Hesse4 Database 3 (DKMA) lead Frank de Vries7 Database 3 (DKMA) backup Montserrat Miret 11 and Jeane Pimienta 12 Database 3 (GPRD) lead Arlene Gallagher/ Dan Dedman /Jenny Campbell 13 Database 3 (GPRD) backup Olaf Klungel 7 Database 4 (Mondriaan) lead Liset van Dijk 7, 9 Database 4 (Mondriaan) backup Yolanda Alvarez 10 Database 5 (THIN) lead Ana Ruigomez 3 Database 5 (THIN) backup Mark de Groot7 and Raymond Schlienger14 WG1 coleads Olaf Klungel7 and Robert Reynolds5 WP2 coleads 1 Universidad de Alcalá, Madrid, Spain 2 Agencia Espanola de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios, Madrid, Spain (AEMPS) 3 Fundación Centro Español de Investigación Farmacoepidemiológica, Madrid, Spain (CEIFE) 4 Lægemiddelstyrelsen (Danish Medicines Agency), Copenhagen, Denmark