The Praying Mantis in Chinese Folklore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colour Transcript

Colour Transcript Date: Wednesday, 30 March 2011 - 6:00PM Location: Museum of London 30 March 2011 Colour Professor William Ayliffe Some of you in this audience will be aware that it is the 150th anniversary of the first colour photograph, which was projected at a lecture at the Royal Institute by James Clerk Maxwell. This is the photograph, showing a tartan ribbon, which was taken using the first SLR, invented by Maxwell’s friend. He took three pictures, using three different filters, and was then able to project this gorgeous image, showing three different colours for the first time ever. Colour and Colour Vision This lecture is concerned with the questions: “What is colour?” and “What is colour vision?” - not necessarily the same things. We are going to look at train crashes and colour blindness (which is quite gruesome); the antique use of colour in pigments – ancient red Welsh “Ladies”; the meaning of colour in medieval Europe; discovery of new pigments; talking about colour; language and colour; colour systems and the psychology of colour. So there is a fair amount of ground to cover here, which is appropriate because colour is probably one of the most complex issues that we deal with. The main purpose of this lecture is to give an overview of the whole field of colour, without going into depth with any aspects in particular. Obviously, colour is a function of light because, without light, we cannot see colour. Light is that part of the electromagnetic spectrum that we can see, and that forms only a tiny portion. -

Wetlands Invertebrates Banded Woollybear(Isabella Tiger Moth Larva)

Wetlands Invertebrates Banded Woollybear (Isabella Tiger Moth larva) basics The banded woollybear gets its name for two reasons: its furry appearance and the fact that, like a bear, it hibernates during the winter. Woollybears are the caterpillar stage of medium sized moths known as tiger moths. This family of moths rivals butterflies in beauty and grace. There are approximately 260 species of tiger moths in North America. Though the best-known woollybear is the banded woollybear, there are at least 8 woollybear species in the U.S. with similar dense, bristly hair covering their bodies. Woollybears are most commonly seen in the autumn, when they are just about finished with feeding for the year. It is at this time that they seek out a place to spend the winter in hibernation. They have been eating various green plants since June or early July to gather enough energy for their eventual transformation into butterflies. A full-grown banded woollybear caterpillar is nearly two inches long and covered with tubercles from which arise stiff hairs of about equal length. Its body has 13 segments. Middle segments are covered with red-orange hairs and the anterior and posterior ends with black hairs. The orange-colored oblongs visible between the tufts of setae (bristly hairs) are spiracles—entrances to the respiratory system. Hair color and band width are highly variable; often as the caterpillar matures, black hairs (especially at the posterior end) are replaced with orange hairs. In general, older caterpillars have more black than young ones. However, caterpillars that fed and grew in an area where the fall weather was wetter tend to have more black hair than caterpillars from dry areas. -

Lesson 3 Life Cycles of Insects

Praying Mantis 3A-1 Hi, boys and girls. It’s time to meet one of the most fascinating insects on the planet. That’s me. I’m a praying mantis, named for the way I hold my two front legs together as though I am praying. I might look like I am praying, but my incredibly fast front legs are designed to grab my food in the blink of an eye! Praying Mantis 3A-1 I’m here to talk to you about the life stages of insects—how insects develop from birth to adult. Many insects undergo a complete change in shape and appearance. I’m sure that you are already familiar with how a caterpillar changes into a butterfly. The name of the process in which a caterpillar changes, or morphs, into a butterfly is called metamorphosis. Life Cycle of a Butterfly 3A-2 Insects like the butterfly pass through four stages in their life cycles: egg, larva [LAR-vah], pupa, and adult. Each stage looks completely different from the next. The young never resemble, or look like, their parents and almost always eat something entirely different. Life Cycle of a Butterfly 3A-2 The female insect lays her eggs on a host plant. When the eggs hatch, the larvae [LAR-vee] that emerge look like worms. Different names are given to different insects in this worm- like stage, and for the butterfly, the larva state is called a caterpillar. Insect larvae: maggot, grub and caterpillar3A-3 Fly larvae are called maggots; beetle larvae are called grubs; and the larvae of butterflies and moths, as you just heard, are called caterpillars. -

Insects Carolina Mantis Mayfly

I l l i n o i s Insects Carolina mantis mayfly elephant stag beetle widow skimmer ichneumon wasp click beetle black locust borer birdwing grasshopper large milkweed bug (adults and nymphs) mantisfly walking stick lady beetle stink bug crane fly stonefly (nymph) horse fly wheel bug bot fly prairie cicada leafhopper robber fly katydid alderfly syrphid fly Order Ephemeroptera mayfly Species List Order Coleoptera black locust borer click beetle This poster was made possible by: nsects and their relatives (arthropods) make up nearly 80 percent of the known animal species. Scientists elephant stag beetle lady beetle Illinois Department of Natural Resources Order Plecoptera stonefly currently estimate that 5 to 15 million species of insects exist. In contrast, 5,000 species of mammals are Order Orthoptera birdwing grasshopper Carolina mantis Division of Education found on our planet. In Illinois, we have more than 20,000 species of insects, and many more likely katydid Illinois Natural History Survey I Order Hemiptera large milkweed bug Illinois State Museum occur, as yet undetected in our state! The scientific study of insects is known as entomology. Entomologists stink bug wheel bug Order Diptera bot fly study insects for many reasons, including their incredible number of species and their wide variety of sizes, crane fly horse fly colors, shapes, and lifestyles. The 24 species depicted on this poster were selected by Michael R. Jeffords of robber fly syrphid fly Order Homoptera leafhopper the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, Illinois Natural History Survey, to represent the variety of prairie cicada Order Phasmida walking stick insects occurring in our state. -

Retrotransposable Elements RI and R2 Interrupt the Rrna Genes of Most Insects (Transposable Elements/Sequence Specificity/Molecular Evolution) JOHN L

Proc. NatI. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 88, pp. 3295-3299, April 1991 Evolution Retrotransposable elements RI and R2 interrupt the rRNA genes of most insects (transposable elements/sequence specificity/molecular evolution) JOHN L. JAKUBCZAK, WILLIAM D. BURKE, AND THOMAS H. EICKBUSH Department of Biology, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY 14627 Communicated by Igor B. Dawid, January 2, 1991 ABSTRACT A large number of insect species have been we have taken advantage of the remarkable insertion speci- screened for the presence of the retrotransposable elements RI ficities ofRI and R2 to determine their distribution in species and R2. These elements integrate independently at specific sites throughout the class Insecta. We present evidence that RI in the 28S rRNA genes. Genomic blots indicated that 43 of 47 and R2 are present in the rRNA genes of most insects. insect species from nine orders contained insertions, ranging in Unexpectedly, we found frequent examples of single insect frequency from a few percent to >50% of the 28S genes. species harboring multiple, highly divergent families ofRI or Sequence analysis of these insertions from 8 species revealed 22 R2 elements within their rDNA loci. elements, 21 of which corresponded to RI or R2 elements. Surprisingly, many species appeared to contain highly diver- AND gent copies of RI and R2 elements. For example, a parasitic MATERIALS METHODS wasp contained at least four families of RI elements; the Insect Species. Forficula auricularia, Libellula pulchella, Japanese beetle contained at least five families ofR2 elements. Mantis religiosa, Popillia japonica, Malacosoma america- The presence of these retrotransposable elements throughout num, Tibicen sp., Sphecius speciosus, Dissoteira Carolina, Insecta and the observation that single species can harbor Leptinotarsa decemlineata, the Xylocopinae species, and the divergent families within its rRNA-encoding DNA loci present Carabidae species were collected from the wild. -

AFTER 1: Historically Cultured Insects After Your Visit to Explore Insects In

AFTER 1: Historically Cultured Insects After your visit to explore insects in ancient history. Just like today, people of the ancient world had complex relationships with insects. Some were considered pests, some inspired mythology, and some were economically important. Students demonstrate understanding of how insect form influences behavior and the characteristics of an ancient culture by creating a “product” that would have been utilized in that culture. VA Standards Addressed English/Language Arts: 2.8; 3.6 Science (2018): 2.1 f; 3.1; f History/Social Science: 3.2; 3.3; 3.4 Materials At least one set of 25 Appendix B: Historical Insect Cards (Appendix B) that identify ways in which insects and other invertebrates were used in the ancient cultures of Mali, Egypt, China, Greece, and Rome. Background Ancient Egypt, Greece, Rome, and China have rich written histories, while the Empire of Mali utilized a more oral history tradition. The former cultures also worked extensively in stone and metal to produce art, while Ancient Mali used more textile, wood, and other biodegradable substances. As a result, I found it difficult to identify insects in the culture of Ancient Mali. The folklore and use of insects presented in this lesson are from oral histories and current cultures of the peoples who now occupy the territory of Ancient Mali, and have likely been passed down through the ages. Lesson Preparation 1. Select a grouping system that works for your students. Each student could get one card, then move around the room to compare with others, pairs could get packs of a few cards, or small groups could each get their own set. -

Db Insect Guide Eng Compress

What are insects? How should I observe insects? Body Insects could be found everywhere- from flowers, divided into: shrubs, soil surface, to the sky and water! Observe carefully and you may discover them! Head You don’t need high-tech equipment to observe 3 pairs of legs Thorax insects. You’ll only need: Abdomen Eyes Camera Magnifier This card Safety rules during observation Insects are invertebrates with an Respect the nature. Do not harm any insects. estimated number of 30 million, forming 85% of world’s species Take away nothing but memories; leave nothing but footprints. Turn off the flashlight while taking photos to avoid disturbing the insects. ©February 2017 WWF-Hong Kong. All rights reserved. How to use this ID guide? Common species The purpose of this ID guide is to identify the in Hong Kong major groups of insects. An identification key English Name should be used to distinguish the species. Scientific Name In the classification system, we will divide organisms according to their body features. Insects belong to “Insec- ta” and are further divided into “orders”. Identify the insect group using the classification guide first, then use the colour coding to flip to the right section. Members of the order Common habitats of the order Characteristics of the Ways to distinguish insects insect order that are similar Behaviour and habits ©February 2017 WWF-Hong Kong. All rights reserved. Classification Guide Lepidoptera Odonata Hymenoptera Orthoptera e.g. butterfly, moth e.g. dragonfly, damselfly e.g. bee, wasp, ant e.g. grasshopper. katydid, cricket Compound eyes Compound eyes Strong Membranous Slender Membranous wings Leathery forewings, hind legs Wings covered with scales wings abdomen membranous hindwings Hemiptera Mantodea Diptera Coleoptera e.g. -

A Garden of Words Un Jardín De Palabras

A Garden of Words Un jardÍn de palabras A bilingual gardening dictionary for elementary schools and after-school gardening programs Un diccionario bilingüe de jardinería para escuelas primarias y programas de jardinería extraescolares SUSAN M. SPECTOR, University of California Master Gardener, Santa Barbara County Publication 8423 Revised Edition ii English to Spanish A Garden of Words ANR Publication 8423 INTRODUCTION Written as a University of California Master Gardener Program project, English A Garden of Words/Un jardín de palabras is a bilingual English- Spanish/Spanish-English dictionary. It is intended as a tool to help both elementary school children and their teachers/leaders communicate in to the garden. With the growing trend to incorporate school gardens in Spanish the curriculum, the need for such a tool has surfaced in bilingual com- munities everywhere. It is suitable for use in schools and in after-school, garden-based, learning settings. The dictionary includes the most common gardening words and phrases. Also provided is a translated and converted metric/U.S. units table. The language is color coded, with English words in green and Spanish words in orange. The publication is divided into two sections: TABLE OF CONTENTS English-to-Spanish and then Spanish-to-English. A Garden of Words/ Un jardín de palabras may be used either as an online resource or Introduction .............ii downloaded as a .pdf printout. Tools ...................1 Measurements ............2 Conversion Table ..........3 Gardening Vocabulary ......4 About This Dictionary and the University of California Gardening Phrases .........7 Master Gardeners of Santa Barbara County Plants ..................8 This dictionary is also a product of the UC Master Gardeners of Santa Barbara County Program. -

Dichotomous Key to Orders

FRST 307 Introduction to Entomology KEY TO COMMON INSECT ORDERS What is a Key? In biological sciences a “key” is a written tool used to determine the taxonomic identification of plants, animals, soils, etc. For this lab, a key will be used to identify insects to Order. More detailed identifications to family, genus and species are beyond the scope of this course, but can be accomplished using appropriate guides available from the library. Taking a Closer Look Because insects are so small, differentiating among species, families and even orders is often difficult. However, examination beneath a hand lens or microscope will allow you to see many of the characters mentioned in the key. Why Use a Key? Sometimes, you can identify an insect quickly by comparing it to pictures in field guides or on the internet. Pictures are a great tool, but the use of a key is essential to guarantee that your identification is accurate. Why? Because some insects, even ones from separate orders, can look almost exactly alike. For example, many flies (order Diptera) look almost exactly like wasps (order Hymenoptera). Using your key, you will find that a fly has 1 pair of wings, whereas wasps have 2 pairs of wings. Key to Adult Insects Only Remember - immature insects and adult insects are often very different. This is especially true for holometabolous (complete metamorphosis) insects where the immature stages are larvae and pupae. The key included in this guide is only useful for keying adult insects to order. Also, this key does not cover other creatures related to insects, like spiders, sowbugs, and centipedes. -

Praying Mantis.Pub

CORNELL COOPERATIVE EXTENSION OF ONEIDA COUNTY 121 Second Street Oriskany, NY 13424-9799 (315) 736-3394 or (315) 337-2531 FAX: (315) 736-2580 Praying Mantis These highly predaceous insects feed on a variety of other insects. They wait to ambush their prey with the front legs in an upraised position that gives them their name. The egg cases may be found on tree twigs and in fields, and for some fun, you may wish to watch them hatch in your own garden next spring. Eggs cases may be gath- ered by cutting the twig you find them on, then tying the case to a branch in your garden. The young come tum- bling out of their case by the hundreds in the spring. Praying mantids are cannibalistic and will eat one another. Only a few will survive under home garden conditions. Phylum, Arthropoda; Class, Insecta; Order, Mantodea Identifying Features Appearance (Morphology) • Three distinct body regions: head, thorax (where the legs and wings are at- tached), abdomen. • Part of the thorax is elongated to create a distinctive 'neck'. • Front legs modified as raptorial graspers with strong spikes for grabbing and holding prey. • Large compound eyes on the head which moves freely around (up to 180°) and three simple eyes be- tween the compound eyes. • Incomplete or simple metamorphosis (hemimetabolous). Adult Males and Females Females usually have heavier abdomen and are larger than males. Immatures (different stages) A distinct Styrofoam-like egg case protects Mantid eggs throughout the winter. Up to 200 or more nymphs may emerge from the egg case. -

Aquatic Insects

Aquatic Insects D-BAIT Lesson Purdue Polytechnic Institute Purdue Dept. of Entomology Photo credit: John Obermeyer, Purdue University Entomology What is an Insect? 1 Insects are: 2 1) Animals which are heterotrophs with internal digestion 3 2) Arthropods, which have an exoskeleton with jointed legs 3) Insects have external mouthparts, three body regions, and six legs https://cals.arizona.edu/pubs/garden/mg/entomology/intro.html • 3 Insect Body Sections: – Head: sensory & feeding – Thorax: movement, legs & wings – Abdomen: reproduction, digestion Aquatic Insect Evolution • All aquatic insects have wings as adults • Primitive “old-winged” insects: mayflies & dragonflies • “New-winged” insects derived folding before metamorphosis evolved: wings stoneflies, true bugs wings • Most recently evolved groups have new folding wings and metamorphosis: flies, beetles, caddisflies, net-winged insects Insect Life Cycles Incomplete metamorphosis Complete metamorphosis - get larger at each molt - immature and adult very different - wing buds appear and increase - wings visibly absent until adult - adult can be aquatic or terrestrial - adult can be aquatic or terrestrial Habitats & Challenges • Habitat is the ecological area inhabited by a species that provides it with nutrition, shelter, and the ability to reproduce (mates, nesting sites, etc…) • Each habitat type presents different benefits and challenges to species Ponds and Lakes Streams and Rivers - Often full of plants - Moving water - Low oxygen content - Higher oxygen content Life in the River -

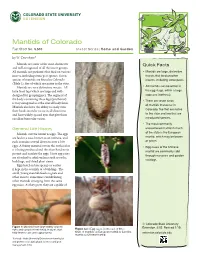

Mantids of Colorado Fact Sheet No

Mantids of Colorado Fact Sheet No. 5.510 Insect Series|Home and Garden by W. Cranshaw* Mantids are some of the most distinctive Quick Facts and well-recognized of all the insect groups. All mantids are predators that feed on various • Mantids are large, distinctive insects, including some pest species. Seven insects that feed on other species of mantids are found in Colorado insects, including some pests. (Table 1), five of which are native to the state. Mantids are very distinctive insects. All • All mantids survive winter in have front legs which are large and well- the egg stage, within a large designed for grasping prey. The segment of egg case (ootheca). the body containing these legs (prothorax) • There are seven kinds is very elongated as is the overall body form. of mantids that occur in Mantids also have the ability to easily turn Colorado, five that are native their heads in order to see in all directions and have widely spaced eyes that give them to the state and two that are excellent binocular vision. introduced species. • The most commonly General Life History encountered mantid in much of the state is the European Mantids survive winter as eggs. The eggs are laid in a case, known as an ootheca, and mantid, which may be brown each contains several dozen to over a 100 or green. eggs. A foamy material covers the oothecal as • Egg cases of the Chinese it is being produced and this then hardens to mantid are commonly sold protect and insulate the eggs. These egg cases through nurseries and garden are attached to solid surfaces such as rocks, catalogs.