Ancient Rome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fractures: Political Identity in the Fall of the Roman Republic by Juan De

Fractures: Political Identity in the Fall of the Roman Republic by Juan De Dios Vela III, B.A. A Thesis In History Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved Dr. Gary Edward Forsythe Chair of Committee Dr. John McDonald Howe Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School August, 2019 Copyright 2019, Juan De Dios Vela Texas Tech University, Juan De Dios Vela III, August 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................... iii INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER I: FOUNDATIONS..................................................................................... 13 Part one: Political Institutions ..................................................................................... 13 Part Two: Citizens, Latins, Colonies and the Social Web .................................... 23 Part Three: Magistrates and Local Control ........................................................... 26 Part Four: Patrons and Clients .................................................................................... 28 CHAPTER II: THE FIRST CRACKS ......................................................................... 32 The Gracchan Seditions ....................................................................................... 32 Impotent Interlopers ............................................................................................ -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 11-09-2006 I, Mark Andrew Atwood, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: The Department of Classics It is entitled: Trajan’s Column: The Construction of Trajan’s Sepulcher in Urbe This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Peter van Minnen William Johnson Trajan’s Column: The Construction of Trajan’s Sepulcher in Urbe A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Classics of the College of Arts and Sciences 2006 By MARK ANDREW ATWOOD B.A., University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 2004 Committee Chair: Dr. Peter van Minnen Abstract Eutropius (8.5.2) and Dio (69.2.3) record that after Trajan’s death in A.D. 117, his cremated remains were deposited in the pedestal of his column, a fact supported by archeological evidence. The Column of Trajan was located in urbe. Burial in urbe was prohibited except in certain circumstances. Therefore, scholars will not accept the notion that Trajan overtly built his column as his sepulcher. Contrary to this opinion, I argue that Trajan did in fact build his column to serve as his sepulcher. Chapter 1 examines the extensive scholarship on Trajan’s Column. Chapter 2 provides a critical discussion of the relevant Roman laws prohibiting urban burial. Chapter 3 discusses the ritual of burial in urbe as it relates to Trajan. Chapter 4 identifies the architectural precedent for Trajan’s Column and precedent for imperial burials in urbe. -

A COMPANION to the ROMAN ARMY Edited By

ACTA01 8/12/06 11:10 AM Page iii A COMPANION TO THE ROMAN ARMY Edited by Paul Erdkamp ACTA01 8/12/06 11:10 AM Page i A COMPANION TO THE ROMAN ARMY ACTA01 8/12/06 11:10 AM Page ii BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO THE ANCIENT WORLD This series provides sophisticated and authoritative overviews of periods of ancient history, genres of classical lit- erature, and the most important themes in ancient culture. Each volume comprises between twenty-five and forty concise essays written by individual scholars within their area of specialization. The essays are written in a clear, provocative, and lively manner, designed for an international audience of scholars, students, and general readers. Ancient History Published A Companion to the Roman Army A Companion to the Classical Greek World Edited by Paul Erdkamp Edited by Konrad H. Kinzl A Companion to the Roman Republic A Companion to the Ancient Near East Edited by Nathan Rosenstein and Edited by Daniel C. Snell Robert Morstein-Marx A Companion to the Hellenistic World A Companion to the Roman Empire Edited by Andrew Erskine Edited by David S. Potter In preparation A Companion to Ancient History A Companion to Late Antiquity Edited by Andrew Erskine Edited by Philip Rousseau A Companion to Archaic Greece A Companion to Byzantium Edited by Kurt A. Raaflaub and Hans van Wees Edited by Elizabeth James A Companion to Julius Caesar Edited by Miriam Griffin Literature and Culture Published A Companion to Catullus A Companion to Greek Rhetoric Edited by Marilyn B. Skinner Edited by Ian Worthington A Companion to Greek Religion A Companion to Ancient Epic Edited by Daniel Ogden Edited by John Miles Foley A Companion to Classical Tradition A Companion to Greek Tragedy Edited by Craig W. -

Lex Canuleia

Lex Canuleia The lex Canuleia, or lex de conubio patrum et plebis, league, Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, and his brother, was a law of the Roman Republic, passed in the year 445 Titus Quinctius Capitolinus Barbatus.[10][11] BC, restoring the right of conubium between patricians [1][2][3][4] Claudius then suggested that military tribunes with con- and plebeians. sular power might be elected from either order, instead of consuls; but he was not willing to bring the matter for- ward himself, delegating the distasteful matter to Titus 1 Canuleius’ first rogation Genucius, brother of the consul, who was of a mind to compromise with the plebeians. This proposal was well- Five years earlier, as part of the process of establishing received, and the first consular tribunes were elected for [10][12] the Twelve Tables of Roman law, the second decemvirate the following year, BC 444. had placed severe restrictions on the plebeian order, in- cluding a prohibition on the intermarriage of patricians [5][6] and plebeians. 3 In popular culture Gaius Canuleius, one of the tribunes of the plebs, pro- posed a rogatio repealing this law. The consuls, Mar- In the novel, Goodbye, Mr. Chips, set in an English cus Genucius Augurinus and Gaius Curtius Philo, vehe- boarding school in the late nineteenth and early twenti- mently opposed Canuleius, arguing that the tribune was eth centuries, the schoolmaster Mr. Chipping describes proposing nothing less than the breakdown of Rome’s so- the law to his Roman history class, suggesting a pun that cial and moral fabric, at a time when the city was faced could be used as a mnemonic device: with external threats.[lower-roman 1] Undeterred, Canuleius reminded the people of the many contributions of Romans of lowly birth, including several “So that, you see, if Miss Plebs wanted Mr. -

Select Republican Political Institutions in Outline

____ APPENDIX: SELECT REPUBLICAN POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS IN OUTLINE (300 before 81; 600 down to 45 Bc; then 900 until SENATE. The main consiliu,’n (“advisory body”) of magistrates, itself consisting mainly of ex-magistrates step aside for others. What the Senate decided Augustus reduced it again to 600). The most senior magistrate available in Rome usually presided, but could the Senate long guided state administration and policy e,zatu.s consultant, abbreviated SC) was strictly only a recommendation to magistrates. But in actual fact, of imperium, triumphs; also the state religion, finance, and preliminary iii almost all matters, including wars, allocation of provinces, (eventually) all extensions in which case it is called patrum auctoritas. The 1isiussion of legislative bills, A SC could be vetoed (by a consul acting against his colleague, or by a tribune), more than advice. SC riltirnurn, first passed in 121, was employed in cases of extreme crisis, but again technically was no ASSEMBLIES (U: POPULUS. COMPOSED OF BOTH PATRICIANS AND PLEBEJANS (NON-PATRICIANS). cum imperia. Gave “military auspices” to consuls, praetors once elected by the Centuriate Assembly; also to dictators, non-magistrates was a consul (or sometimes apparently a practor); in Aserubly Validated in some way the powers of lower magistrates (aediles, quaestors). Its president curiae (“wards”) of the city. (c mitia Cicero’s day, it was enough for a lictor symbolically to represent each of the 30 voting (‘101010) (“infantry”), the latter divided into five classes, Centuriate Originally the army, which had centuriae as its constituent units. Equites (“cavalry”) and pedites A of these 193 voting units, not absolute A ,seni hlv ranked by census wealth, totalled 188 centuries; added to those were five unarmed centuries. -

Chapter 3 Early Rome

Chapter 3 Early Rome 1. THE WARLIKE MEDITERRANEAN Romans lived in a dangerous neighborhood. The whole of Italy was an anarchic world of contending tribes, independent cities, leagues of cities, and federations of pre-state tribes. The Mediterranean world beyond Italy was not much differ- ent. During the period of Rome’s emergence (ca. 500–300 b.c.) the Persian Empire consolidated its hold on the Middle East and the eastern Mediterranean, including parts of the Greek inhabited world, and for two centuries independent Greek city- states and Persians confronted each other, sometimes belligerently, and sometimes as allies. Simultaneously, individual Greek city states waged wars with each other as did alliances of Greek states among themselves. Wars lasted for generations. The great Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta and their allies raged in two phases from 460 to 446 b.c. and from 431 to 404 b.c. Sixty-five years later, Mace- donians subdued the squabbling city states of Greece, bringing a kind of order to that war-torn land. Four years after defeating the Greeks, the Macedonians under Alexander the Great went on to conquer the Persian Empire. Their power reached from the Aegean to Afghanistan and India, but not for long as a unified state. After Alexander’s death his successors quarreled and fought each other to a standstill. While these wars were going on in the eastern Mediterranean the Phoenician colony of Carthage emerged as a belligerent, imperialistic power in the western Mediterranean. Just a three- or four-day sail from Rome, Carthage was potentially a much more dangerous than any power in Italy. -

Romanrepublic Part II

z From monarchy to Republic . Magistrates took the role of the king and spread the power among the rich and powerful. Phenomenon in various cities (remember so far, the political organization is at a local level, no unified greater region yet). Frequent displacement of kings in various cities. Ideological aversion to monarchy and tyranny. Predominance of CONSULSHIP would not become as fixed until later in the 4th century. Things are still fluid in the first couple of centuries of the Republic. TWO Consuls. z z TWELVE TABLES . Let’s look at what we know about the earliest legal system in place. The so called TWELVE TABLES were Rome’s first written law (mid 5th century), also can be seen as a first ‘constitution’ as the law code of the twelve Tables mentions the ‘greatest assembly’ that gives judicial rulings. The very word ‘greatest’ implies the existence of many assemblies. z Content of Twelve Tables . Not a law in the modern sense of the word . Did not attempt systematic treatment of all the law but was more of a collection of specific and rather narrow provisions, a better fit for a society where the household is the foundational unit of social life and has not yet evolved politically. Addressed issues of inheritance, marriage and divorce, rights of the father of the household (PATRIA POTESTAS), regulated land boundaries, farm buildings and fences, slaves, and specified penalties. z z z z What exactly was the Role of the Senate? . The Senate . Under the king, the Senate was only an advisory committee who ratified election of the king by the popular assemblies. -

379330.Pdf (14.81Mb)

AUGUSTUS AND LAW-MAKING Elizabeth Clare Tilson Doctor of Philosophy University of Edinburgh 1986 ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis is to establish the significance of the Augustan period in the history of law-making and of various important areas of Roman Law. Clearly, the demise of the Roman Republic and the emergence of a princeps could not fail to be reflected in a system which had evolved, along with the Republic itself, over five centuries, and which was, therefore, closely linked with Republican institutions and processes. The varied Republican channels of law-making continued to be employed under Augustus, but never before had one man enjoyed sufficient power and auctoritas to enable him to oversee a large law-making programme as Augustus did. In chapter 1, i survey briefly the many enactments which are attributed in the evidence to the Augustan period after about 19 B. C., particularly those which can confidently be categorised as statutes, senatusconsulta or edicts, in order to see what happened to the Republican sources of law under Augustus and to look at the sorts of issues which were regulated by law during the Augustan period. The remaining chapters are devoted to the most important and best documented Augustan statutes, the lex Iulia de maritandis ordinibus and the lex Papia Poppaea (chapters 2 and 3), the lex Iulia de adulteriis coercendis (chapter 4) and the lex Aelia Sentia and the lex Fufia Caninia (chapter 5). The purpose of these chapters is to examine the individual statutes in detail and to see what policies and aims may be detected in them in order to assess their importance in the history of these areas of Roman Law and as reflections of the aims and achievements of Augustus in general. -

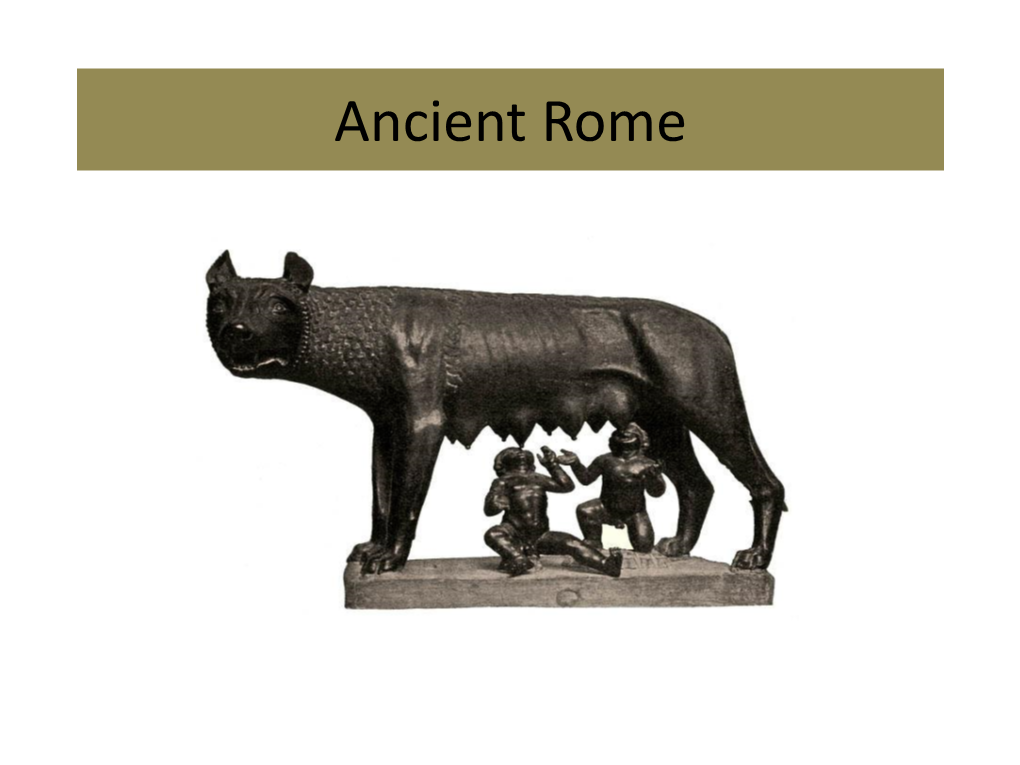

The Roman Republic By: Jacob, Jackson, Insiya, Logan the Legendary Founding of Rome

The Roman Republic By: Jacob, Jackson, Insiya, Logan The Legendary Founding of Rome • According to legends, the ancient city was founded by two brothers named Romulus and Remus. • In an argument over the city name (or possibly location) Romulus killed Remus and named the city after himself. • Another theory says the city is named after a woman, Roma, who traveled with Aeneas and other survivors of the Trojan war. • The men wanted to continue past the Tiber River, but Roma objected, and she teamed up with other women in the group to burn the Trojan ships and start a new settlement on the banks of the Tiber. Etruscan Rule • Shortly before 600 BC Rome was conquered by several Etruscan princes from across the Tiber River. • Tarquinius Priscus, the first of the Etruscan kings, drained the city's marshes. He improved the Forum, which was the commercial and political center of the town • Under Servius Tullius, the second Etruscan king, a treaty was made with the Latin cities which acknowledged Rome as the head of all Latium. • The last of the kings of Rome, Tarquinius Superbus, was a tyrant who opposed the people. He scorned religion. • Under the rule of the Etruscans Rome grew in importance and power. Great temples and impressive public works were constructed. • Trade prospered, and by the end of the 6th century BC. Rome had become the largest and richest city in Italy. Etruscan Rule Continued... • Under the Etruscan Kings, Roman society was divided into two classes - Patricians - Plebeians • The Patricians class controlled most of the land, held important offices, and advised the Etruscan king. -

The Telos of Government

Xavier University Exhibit Honors Bachelor of Arts Undergraduate 2018-03-26 Democracy vs. Liberty: The eloT s of Government Ryan C. Yeazell Xavier University, Cincinnati, OH Follow this and additional works at: https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/hab Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Ancient Philosophy Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, and the Other Classics Commons Recommended Citation Yeazell, Ryan C., "Democracy vs. Liberty: The eT los of Government" (2018). Honors Bachelor of Arts. 35. https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/hab/35 This Capstone/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate at Exhibit. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Bachelor of Arts by an authorized administrator of Exhibit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Democracy vs. Liberty: The Telos of Government Ryan Yeazell HAB Capstone Thesis Dr. Strunk March 26, 2018 1 Introduction In 2005, after decades of civil war, the people of South Sudan were victorious against the northern Republic of Sudan and created their own autonomous government. They followed the modern trend of instituting democratic elections and a presidential system, with a bicameral legislature and an independent judiciary. The young regime employed all the building blocks of a modern stable democracy. By 2011, South Sudan declared its full independence from the Republic of Sudan. The country was admitted to the United Nations and internationally recognized as Africa’s newest state. But the stability and legitimacy of this auspicious beginning quickly deteriorated. Within two years, ethnic tensions turned into outright conflict, the President and Vice President led armies against each other, and all the stability that a democratic regime was expected to offer was nowhere to be found. -

D. a Written Constitution for Rome 1. the Importance of Written Laws A

www.HistoryAtOurHouse.Com Lower Elementary Class Notes D. A Written Constitution for Rome 1. The Importance of Written Laws a) Written laws are important because when the people know the laws, they can make sure to follow them (and thus avoid being criminals), but also because people who know the law can more easily change the laws, or even rebel against them if they are very unfair. 2. The Second Secession of the Plebeians (449 BC) a) The plebeians wanted written laws, but the patricians did not like the idea of having another limit placed on their power. b) In order to force the patricians to make the change, the plebeians seceded again. 3. The Laws of the Twelve Tables a) The final set of laws produced are known as the “Laws of the Twelve Tables” because they were engraved on twelve bronze tablets. b) The laws were placed on display in the center of the city. c) Sadly, the tables were destroyed by the Gauls in a war with Rome c.390 BC. E. Lex Canuleia (445 BC) 1. The constant desire of patricians to have power over the plebeians stemmed from the belief that patricians were superior (in every every important way) to plebeians. 2. Because they thought they were superior, patricians made it illegal for patricians to marry plebeians. 3. Gaius Canuleius, a tribune, pushed for this law to be changed. 4. The Lex Canuleia (“lex” means “law”), obviously named after him, made it legal for plebeians to marry patricians. F. The Patrician Reaction: Censorship 1. The patricians were worried that plebeians would ruin the character of their noble families. -

The Refusal of the Centuriate Assembly to Declare War on Macedon (200 BC) — a Reappraisal

The Refusal of the Centuriate Assembly to Declare War on Macedon (200 BC) — A Reappraisal Rachel Feig Vishnia The question why Rome decided to declare war on Macedon in 200 shortly after the conclusion of the long and exhausting Hannibalic war remains in many ways unanswered. Modem scholarship is skeptical about the reasons given by Livy, our only source for this affair. As a result, the motives behind Rome’s decision, which proved to be a milestone in the development of ‘Roman Imperialism’, are widely interpreted and much debated.1 Less attention has been paid both to the initial refusal of the centuriate assembly to approve this war on grounds of war weariness and to the potential implications of this refusal.2 Those who consider this unprecedented popular rebuttal tend to emphasize the fact that the people, intimidated by the consul’s warning of the due consequences if Philip V was allowed to invade Italy, were eventually persuaded to vote for the war.3 Others focus on the period of time that elapsed between the two war votes, which is not specified in the sources, and discuss these in relation to the complex chronology of the events spanning the (second) war vote and the dispatch of the armies to Macedon towards the end of the autumn of 200 (Livy 31.22.4 autumno ferme exacto),4 However, the grounds both for the people’s initial refusal and for the Cf. Livy 31.1. M 0. For review and criticism of previous views, and for a plau sible conjecture see E.S.